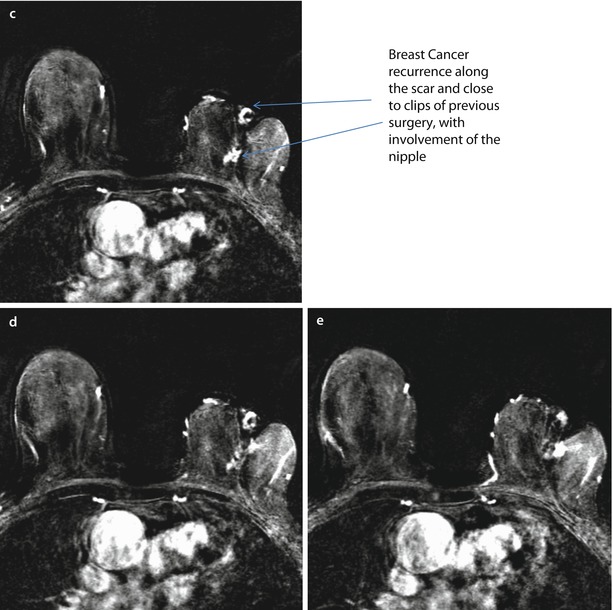

Fig. 22.1

Patient aged 80, submitted to quadrantectomy 17 years before because of an IDC, 10 mm, G2, ER+, PgR+, Her2−, Ki67 15% in the left breast. Breast cancer recurrence at MRI along the scar and close to the clips of previous surgery, with involvement of the nipple. Evidence of the surgical clip a and scar b on T1-weighted images. Several foci of suspicious enhancement along and next to the scar with an involvement of the nipple after the injection of contrast medium and subtraction of images c–e. Histology revealed IDC, G2 ER+, PgR−, Her 2−, Ki67 10%

However, there are no published or pending incontrovertible data suggesting a real advantage in terms of overall survival for total mastectomy versus second conservative surgery as a surgical approach in IBTR patients [27–29]. A recent cohort study using propensity score analysis showed no difference in distant disease-free survival (DFS) or overall survival between mastectomy and second breast-conserving surgery after IBTR [30]. Further breast-conserving surgery is the subject of intense debate at present. Gentilini and colleagues suggested that the subset of patients with a recurrent tumour <2 cm in size, occurring >48 months after primary surgery, may be suitable for breast preservation [31]. Ishitobi and colleagues have suggested that oestrogen receptor positivity may also be considered as potential criteria for further conservation [32]. Obviously, other general criteria for correct selection of patients for a second breast-conserving surgery are the patient’s desire for a conservative approach and a reasonable likelihood of an acceptable cosmetic result.

Ideally, to rigorously assess the oncological safety and other outcomes of secondary conservation surgery compared to mastectomy for surgical management of IBTR after breast-conserving therapy, it would be desirable to design a phase III randomized clinical trial comparing salvage mastectomy versus second breast-conserving surgery (probably with re-irradiation), although some concerns regarding trial design are still unclear, such as the best primary endpoint (local control or disease-free and overall survival) and the number of patients to be enrolled. Such a trial would be challenging as a low event rate would mandate a large sample size, long follow-up would be required, and it is highly probable that many patients would refuse randomization, due to strong personal preferences about surgery.

22.3 Ipsilateral Breast Tumour Recurrence After Mastectomy

Local recurrences after mastectomy tend to present relatively early, as an asymptomatic nodule(s) in the skin near the scar of the mastectomy (◘ Fig. 22.2). These are usually high-risk patients from the outset with involved axillary nodes, lack of systemic therapy, adverse disease biology, and advanced T stage of the primary tumour. Their onset is significantly earlier than IBTR after breast-conserving surgery [33] usually in the first few years after mastectomy. The vast majority of local recurrences after mastectomy are within the first 5 years from surgery, ranging from 60 to 85% within the first 3 years [33, 34]. Furthermore, the outcome of these patients is generally poor, although some subgroups of patients seem to have a more favourable prognosis. A worse prognosis is related to pT3–4 disease, nodal involvement, grade III, oestrogen receptor negative tumours and short time to recurrence (<1 year) [35]. In another study at Memorial Sloan Kettering, the major predictive factors for isolated locally recurrent breast cancer after mastectomy were young age, lymphovascular invasion and multicentricity [36]. Elective post-mastectomy radiotherapy reduces the risk [3] in selected patients, as well as systemic adjuvant treatment [37].

Fig. 22.2

BRCA1 mutation carrier, aged 54, submitted to mastectomy 5 years before for extensive DCIS combined with multicentric IDC, with the largest single lesions of 20 mm, (G2, ER+, PgR+, Her2−, Ki67 10–30%) in the left breast and contemporary breast reshaping on the right. MRI evidence of breast cancer recurrence on the left and cancer development on the right. On T1-weighted images, there is evidence of the prosthesis on the left and several surgical granulomas on the right breast a–c. Subtracted images after injection of contrast medium. There are two suspicious new enhancing nodes on the left, close to the prosthesis d, e and several enhancing, irregular foci of enhancement on the right both along the scar of previous reshaping and within the parenchyma f. FNAB revealed IDC, ER+, PgR−, p185+ on the left and IDC G2 on the right

A multidisciplinary approach is required for optimal management of local recurrence after mastectomy [38]. Rather than systemic hormonal or chemotherapeutic treatment, a surgical approach may be the best choice for local control of disease but can be performed only in favourable cases, if the size and the location of the recurrence permit this. In general, surgical excision for post-mastectomy recurrence must be as wide as possible and ideally at least two or three cm from the nodule, particularly if the area to be excised shows more than one nodule. In many cases use of a flap-based technique or even skin grafting to close the defect will be required. The width of surgical excision will depend on the local extent of the recurrence, whether the tissues have been previously irradiated which reduced tissue elasticity and will impair wound healing if any tension is present in the wound closure, invasion of the chest wall and the laxity of the residual chest wall skin. When surgery is not feasible, other local therapeutic options may be radiotherapy (the possibility has to be carefully evaluated if the skin has been previously irradiated) or electrochemotherapy combined with a range of systemic therapies [36, 39].

22.4 Breast Irradiation for Locally Recurrent Breast Cancer and Second Breast-Conserving Surgery

Some trials have been performed to evaluate potentially safe radiotherapeutic techniques to be used after a second breast-conserving surgery. Interstitial brachytherapy is the most widely applied technique, with some technical variants, including low, pulsed or high dose rate [40–42]. The results of this approach seem promising with a low rate of severe toxicity and good cosmetic results and appear to be comparable with salvage mastectomy in terms of oncologic outcomes [40–42]. However, these techniques are highly specialized and complicated and published experience is extremely limited. In addition the added value of adding brachytherapy to second breast-conserving surgery versus surgery alone is not yet clear. Further early trials reporting external beam re-irradiation with electron therapy to the tumour bed [43] or intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) [44] may be easier options but need to be verified in larger studies.

22.5 Reconstructive Surgery for Ipsilateral Breast Tumour Recurrence After Breast-Conserving Surgery or Mastectomy

Reconstructive surgery for locally recurrent breast cancer is a challenge, with significant potential problems faced and a lack of established consensus guidelines. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the main problem is radiotherapy, either the previous adjuvant radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy, or, in cases where this was omitted during treatment of the primary, it is highly likely to be advised after surgery for recurrence [45].

In case of salvage mastectomy for locally recurrent cancer after breast-conserving surgery, an implant-based breast reconstruction may be difficult with a considerably higher rate of complications related to the previous adjuvant radiotherapy. Additional trials need to be carried out to determine if immediate 1-stage or 2-stage prosthetic breast reconstruction can be performed successfully in selected patients [46]. The rate of early complications in this patient group is higher than in the non-irradiated cohort but remains acceptable [47, 48]. Women considered for this must have very good skin elasticity and quality and no evidence of post-radiation damage. Smokers must be excluded and particular attention should be given to the use of atraumatic surgical technique, avoidance of tension on the wounds and excellent postoperative care. The use of biological (ADMs) and synthetic meshes for breast reconstruction has increased during the last 5 years, although caution must be exercised when using these meshes in irradiated patients as no randomized trials have been conducted and their use is associated with higher rates of infection in most series [49].

In many cases autologous flap reconstruction, from the abdomen or from the back, may be the first or the only reconstructive option for patients who develop local recurrence following earlier breast-conserving surgery [50–52]. Only autologous tissue reconstruction has been shown to have an acceptable rate of complications comparable to those of primary reconstruction. Khansa and colleagues evaluating 802 breast reconstructions reported that radiation in the setting of breast-conserving surgery did not increase the overall rate of complications or dissatisfaction with subsequent breast reconstruction if autologous reconstruction was performed in the majority of cases [53]. However, they found a higher incidence of mastectomy skin flap loss, but this did not represent a major issue if a healthy autologous flap was underneath the skin (DIEP, TRAM, LD, etc.).

Patients with locally recurrent breast cancer who have previously had mastectomy and implant reconstruction are generally offered a new wide excision. The challenge is to satisfy oncologic radicality and preserve the previously inserted implant: the closure may be too tight due to loss of the skin and soft tissue coverage. Alternatively, a smaller implant, able to achieve a moderate level of symmetry, may be considered [54]. Subsequent symmetrization may be offered if required.

Patients should be informed about the possible long-term complications of postoperative radiotherapy treatment to a reconstruction and in particular the higher rates of implant loss, capsule formation and progressive asymmetry [55].

However, even in these cases, autologous reconstruction may be the best option to reduce local short- and long-term complications, which probably outweigh the disadvantage such as more prolonged surgery and donor-site morbidity. [56] Furthermore, in case of large excisions and those in need of postoperative radiotherapy, the option of delayed reconstructive flap surgery may be considered to ensure that the new autologous breast-like tissue has sufficient long-term softness [57].

Conversely, when flap reconstruction is not an option, for example, where previous surgery has already used a particular donor site or there are other contraindications, a two-step breast reconstruction may be the only possibility, although multiple fat-transfer procedures become necessary to improve tissue vitality before substituting the expander with the implant. In these cases, radiotherapy may be performed with the expander in situ [58].

Immediate flap reconstruction for locally recurrent breast cancer may have two other advantages: firstly, a further local recurrence can be easily detected and, secondly, it may be easily managed, considering that breast mound reconstruction with autologous tissue even after wide excisions may be effectively reshaped with a good breast contour in most cases [59] (◘ Fig. 22.3).

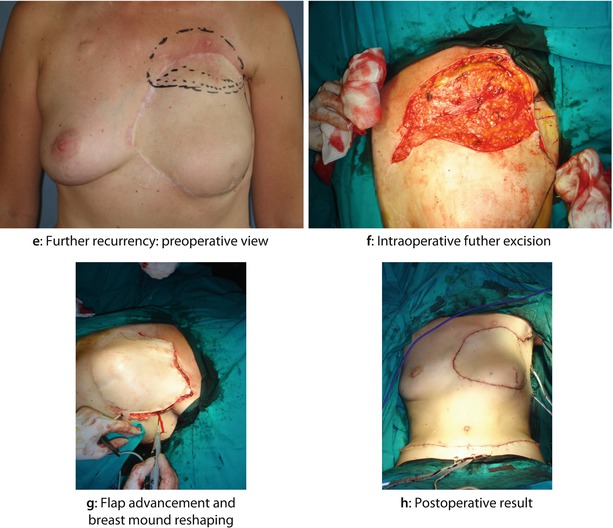

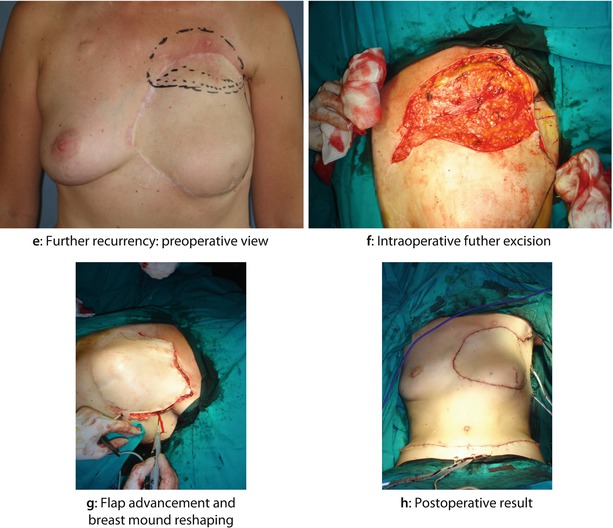

Fig. 22.3

A 35-year-old woman had a widespread cutaneous LRR almost 2 years after BCS followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The primary tumour was G3, oestrogen and progesterone-receptor negative, HER2+, ductal invasive breast cancer associated with an extensive intraductal component and heavy axillary node involvement. After the histological diagnosis of LRR, the patient was treated with further cycles of second line chemotherapy with Herceptin, apparently obtaining a clinical good control of local disease. The patient then underwent mastectomy with wide excision of the skin of the anterior chest wall and reconstruction with bipedicled TRAM flap. A second LRR, 2 years later, was successfully treated with further resection, flap advancement and breast mound reshaping: a Preoperative view of breast skin LRR after BCS. b Intraoperative view after wide excision. c Intraoperative view of bipedicle TRAM flap reconstruction. d Postoperative result after 1 month. e Further recurrence: preoperative view. f Intraoperative further excision. g Flap advancement and breast mound reshaping. h Postoperative result

22.6 Axillary Staging in Locally Recurrent Breast Cancer

Until 15 years ago, axillary dissection was the gold standard in any case of primary breast cancer, although the management of axillary nodes had progressively changed from a therapeutic option to a largely staging procedure for planning adjuvant treatment for most women [60] as less invasive sentinel node biopsy has superseded axillary dissection in women with a clinically negative axilla [61–63].

Consequently, the type of axillary restaging in cases of isolated local recurrence, with previous sentinel node biopsy and without gross nodal metastases at the time of local recurrence, has been widely debated because the non-dissected axilla leaves all possibilities open (no surgery, re-operative sentinel node biopsy, or axillary dissection). However, although much clinical evidence has been collected, there is no consensus to standardize practice at present.

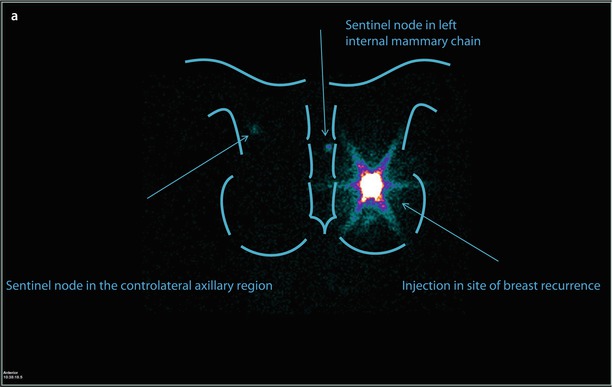

At the beginning of the sentinel node era, previous axillary surgery was considered a strong contraindication, although much data have been progressively reported to refute this concept, including several large series [64–66]. The rate of detection and removal of re-operative sentinel nodes is substantially lower than those of sentinel nodes for the primary tumour in all series evaluated (likely due to a combination of previous axillary surgery and breast radiotherapy), even if repetition of sentinel node biopsy is technically safe, feasible and accurate [64–66]. A possible solution for improving the detection rate of re-operative sentinel nodes might be injection of a larger amount of tracer (>180 MBq) [67] or performing a dual technique (lymphoscintigraphy and blue dye). The basic concept is that, after a previous axillary operation, in case of partial blockage of lymph flow, an axillary sentinel node may still be found, consistent with the hypothesis that breast tumours drain through common afferent lymphatic vessels from a sub-areolar plexus; even in case of complete interruption of lymphatic flow, this is only temporary because the lymphatic plexuses will have re-grown in the time between previous surgery and IBTR [68]. The issue of a possible alteration of lymphatic drainage pathways after previous sentinel node biopsy has been evaluated in a recent meta-analysis, showing that only in 17.4% of cases was an aberrant drainage pathway observed and that the predominant locations were in the contralateral axilla and internal mammary chain (◘ Fig. 22.4) [69]. The same meta-analysis also reported that the sentinel node was involved in 19.2% of patients and that 27.5% of these metastases were in the aberrant lymph drainage basin [69].

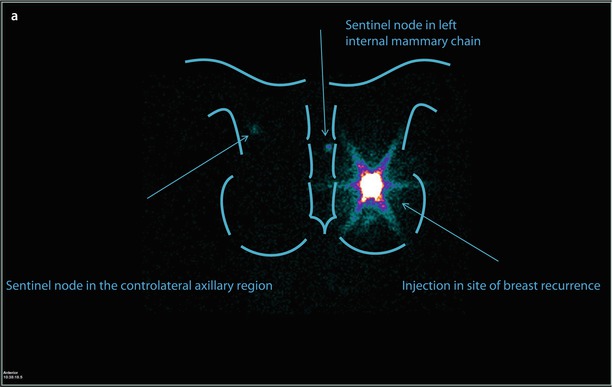

Fig. 22.4

Patient aged 49, previously operated with left breast quadrantectomy and axillary sentinel node biopsy/sampling, because of an IDC pT2 (22 mm) (G3, ER and PgR−, Her2+, Ki67: 70%); N0(0/7); M0 tumour. The patient was treated with CT (FEC x6), RT and trastuzumab. Eleven years later, mammography and ultrasound detected a suspicious nodule in the same area of the breast parenchyma. Biopsy confirmed the presence of IDC, G3, ER and PgR−, Her2−, MIBI 90%. Lymphoscintigraphy depicted one sentinel node in left internal mammary chain and one in contralateral axillary region a, but PET scan examination showed breast recurrence without evidence of nodal uptake b

In a very recent report, Ugras and colleagues showed, in a limited series of 83 patients, that re-operative sentinel node biopsy is feasible, but the risk of axillary failure and rates of disease-free survival or overall survival are comparable to patients who did not receive any axillary restaging at the time of local failure, subsequent conservative surgery or mastectomy [70].

22.7 Indication and Need for Systemic Treatment After Locally Recurrent Breast Cancer

Patients with locoregional failure after breast-conserving surgery have an increased risk of distant disease and death from cancer [71].

In a retrospective review of 10 National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) clinical trials involving 6468 patients treated with conservative surgery, 5-year distant-free survival after an ipsilateral breast tumour relapse was 67% in node negative tumour and 51% for node positive cancers. Other locoregional recurrence such as nodal and chest wall recurrence resulted in a DFS of 19–29% in node positive and node negative women, respectively [71, 72].

Even if chemotherapy is largely used to decrease the risk of recurrence after a resected locoregional recurrence in breast cancer, few randomized trials have been conducted in this clinical setting.

Several randomized trials have prematurely closed due to low rate of accrual justified by the issue to randomize patients with high risk of recurrence to the no chemotherapy arm.

The CALOR trial is the first randomized trial to confirm evidence of chemotherapy benefit in patients with histologically proven and completely excised isolated local recurrences (ILRR). The initial planned sample was almost 1000 patients but was later amended to 276 and final enrolment was 162 patients with a recruitment period of 7 years. In this worldwide, open label trial patients were randomized to physician’s choice of chemotherapy (polychemotherapy for at least four cycles) or no chemotherapy. The primary endpoint was DFS.

Globally, 162 patients were enrolled with a median age of 56. Most patients in both groups had ILRR surgery at least after 2 years from diagnosis of breast cancer. At a median follow-up of 4.9 years, the 5-year DFS was 69% (95% CI 56–79) in patients treated with chemotherapy versus 57% (95% CI 44–67) in patients randomized to no chemotherapy (the hazard ratio was 0.59 and p = 0.046). Chemotherapy reduced both distant and second local relapse event. Overall survival (OS) was also significantly longer in patients randomized to chemotherapy (5-year OS was 88% in the chemotherapy group versus 76% in the control arm (HR 0.41, p = 0.024)). For DFS the interaction between treatment group and oestrogen receptor status suggests a larger benefit in patients with oestrogen receptor negative cancers, but the sample size is too small to address this issue more specifically [73].

Similarly few trials have addressed the use of endocrine treatment after locoregional relapse. A Swiss trial, SAKK 23.82, compared tamoxifen (TAM) with observation after complete excision of the ILRR and adequate radiotherapy. At a median follow-up time of 11.6 years, the median post-ILRR disease-free survival (DFS) was 6.5 years with TAM and 2.7 years with observation (P = 0.053). The difference was mainly due to reduction of further local relapses (P = 0.011). The OS was 11.2 and 11.5 years in the observation and TAM groups, respectively [74]. Decisions about the use of adjuvant chemotherapy or endocrine treatment for locoregional recurrence, the type and duration used, follow the criteria used in the adjuvant setting for a primary tumour. As adjuvant chemotherapy and hormonal treatment reduce the risk of local and distant relapse and increase overall survive after primary breast surgery, adjuvant hormonal and chemotherapy should also act on the risk of relapse and death in patients with completely excised locoregional recurrence.

22.8 Conclusion

In conclusion, surgery for treating IBTR is complex and surgeons should try to first establish whether the new lesion is a true IBTR or a less aggressive new primary breast cancer. All patients with IBTR must undergo full staging to diagnose metastatic disease, especially in women with recurrence after mastectomy or others with high-risk characteristics. Patients must have complete information about the benefits and risks of their planned surgery, discussing cosmetic outcomes, the potential for asymmetry and the need for some type of bilateral reshaping in case of second breast-conserving surgery and, if not possible, about the limitation of reconstructive options in case of previous mastectomy and whole breast radiotherapy. Furthermore, the correct evaluation of histologic and biomolecular characteristics of the locally recurrent breast cancer should be made for correct postoperative planning. Finally, a multidisciplinary approach is mandatory for the best clinical results, and specific consideration is needed regarding whether further radiotherapy is advised or possible and whether further systemic therapies are warranted. The evidence base for these decisions is currently poor however.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree