Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Timothy Craig Allen

Squamous cell lung cancer remains the most common histologic type of lung cancer worldwide; however, in the United States, Canada, Japan, and China, due to differences in smoking behavior and cigarette designs, adenocarcinoma has replaced squamous cell carcinoma as the histologic type of lung cancer with the highest incidence.1,2 In the United States, squamous cell lung cancer peaked in incidence in 1981 in men; however, it continues to rise in incidence in women.1 Currently, squamous cell carcinoma makes up approximately 30% of lung cancer diagnoses in the United States.3

Cigarette smoking is the primary etiology of squamous cell lung cancer; however, other associations have been identified, including radiation, arsenic, and chloromethyl ether exposures. A diet high in fruits and vegetables may have a protective effect on the development of squamous cell lung cancer.1 Because squamous cell lung cancer is frequently central, that is, arising within the mainstem bronchi, lobar bronchi, or segmental bronchi, sputum cytology for preneoplasia and early invasive tumors has been attempted; however, currently bronchoscopy detects fewer than 40% of in-situ lesions. While autofluorescence bronchoscopy is more sensitive, it has a high false-positive rate caused by goblet cell hyperplasia and inflammatory lesions.1,4

Clinically, patients with centrally located squamous cell carcinoma often present with obstructive symptoms including cough, wheezing, increased amounts of sputum production, or hemoptysis. Many centrally placed tumors present symptomatically while still relatively small due to their propensity to obstruct, with associated postobstructive pneumonia and mucostasis. Central necrosis is frequently a feature of squamous cell lung cancers, especially larger tumors.1,2 and 3,5 Peripheral squamous cell carcinomas are more likely to be associated with dyspnea and chest pain.1,2 and 3,5,6 Radiologically, central squamous cell carcinomas may exhibit lung collapse, mediastinal shifting toward the side involved with tumor, and, in cases with perihilar and mediastinal extension of tumor, perihilar and mediastinal masses. Peripheral tumors often radiologically exhibit solitary tumor nodules and masses, many of which may show central cavitation and lucency. Pleural effusions may occur. So-called Pancoast tumors, arising in the superior sulcus, often radiologically exhibit posterior rib destruction and clinically Horner syndrome.2,3 and 4,7,8

The specific histological diagnosis of the non-small cell carcinomas of the lung, including accurate diagnosis of squamous cell lung carcinoma, has become increasingly important as new, novel therapies have evolved that depend upon accurate differentiation of non-small cell lung carcinomas as squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or large cell carcinoma.9,10,11,12,13,14 and 15 Limited, including frequently cytologic, sampling of lung tumors and lung cancer heterogeneity are confounding factors in accurate diagnostic typing of non-small cell carcinomas.16 Second-line treatments with bevacizumab, pemetrexed, erlotinib, or docetaxel may be of benefit in some patients who have lung cancers with “predominantly nonsquamous histology.”17 Indeed, differentiating adenocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma is extremely important prior to beginning pemetrexed or bevacizumab therapy (see Chapter 22).

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA, CYTOLOGY

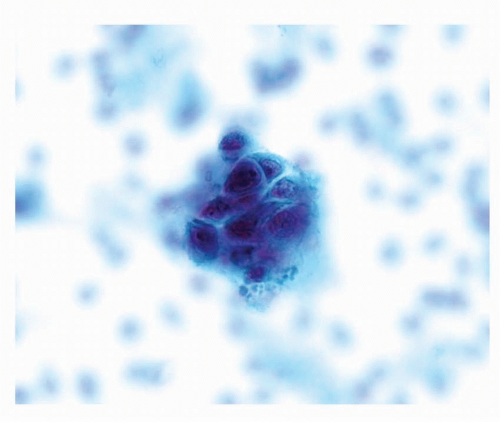

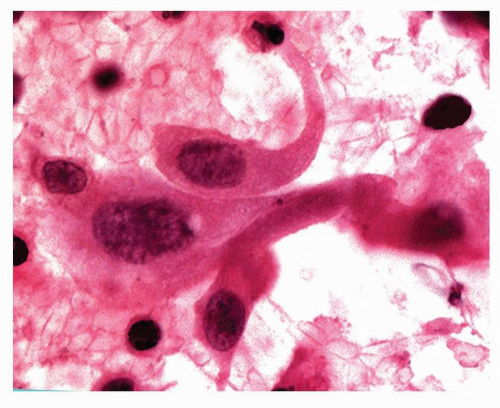

Sputum cytology may contain single tumor cells or small clusters of tumor cells, and bronchial brushings and fine-needle aspiration specimens may contain sheets of tumor cells (Fig. 6-1).3 Tumor cell nuclei may be hyperchromatic, with an “ink dot” appearance, and poorly differentiated tumors may contain prominent nucleoli. Some tumor cells may have irregular shapes such as “tadpole” cells (Fig. 6-2). Cytoplasm may be densely orangophilic, or, on Pap stain, cyanophilic (Fig. 6-3).3

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA, GROSS FEATURES

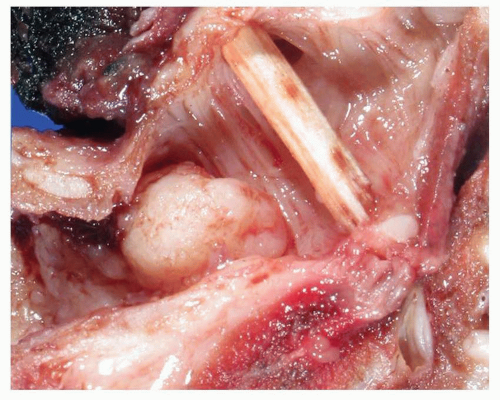

About two thirds of squamous cell carcinomas are centrally located tumors.3 Excised tumors are variably fibrotic, ranging from white to gray-tan, and may be centrally cavitated. Central tumors may show polypoid luminal

tumor growth with associated infiltration of tumor into bronchial wall and surrounding lung parenchyma and hilum (Figs. 6-4 and 6-5). Partial or complete luminal obstruction is frequent, with associated postobstructive pneumonia and mucostasis. Peripheral tumors are variably sized nodules or masses that may show an expansile or stellate growth pattern, with or without central necrosis.1,2 and 3,18,19 and 20 Pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma is defined by the WHO as “a malignant epithelial tumor showing keratinization and/or intercellular bridges that arises from bronchial epithelium.”4

tumor growth with associated infiltration of tumor into bronchial wall and surrounding lung parenchyma and hilum (Figs. 6-4 and 6-5). Partial or complete luminal obstruction is frequent, with associated postobstructive pneumonia and mucostasis. Peripheral tumors are variably sized nodules or masses that may show an expansile or stellate growth pattern, with or without central necrosis.1,2 and 3,18,19 and 20 Pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma is defined by the WHO as “a malignant epithelial tumor showing keratinization and/or intercellular bridges that arises from bronchial epithelium.”4

FIGURE 6-1 High power of Pap stain of sputum specimen containing squamous cell carcinoma showing a three-dimensional cluster of tumor cells with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei and dense cytoplasm. |

FIGURE 6-2 High power of Pap-stained cytology of pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma showing a tadpole cell and some “inkblot” nuclei. |

FIGURE 6-3 High power of Pap-stained squamous cell carcinoma cytology showing a tumor cell with an enlarged atypical nucleus and dense keratinized cytoplasm. |

FIGURE 6-4 Gross image of lung containing squamous cell carcinoma with widespread necrosis and a large area of central cavitation. |

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA, HISTOLOGY

Squamous cell carcinomas histologically contain intercellular bridges or keratinization in the form of keratin pearls or single-cell keratinization ( Figs. 6-6,6-7 and 6-8).2,3 Although the amount varies with the degree of tumor differentiation, single-cell keratinization, squamous pearl formation, or intercellular bridges are required for the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma. In poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinomas, careful inspection may be required to make the diagnosis.

Tumors that show squamoid features but without single-cell keratinization, squamous pearl formation, or intercellular bridges, should be diagnosed as large cell carcinoma and not as poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.1,2,3 and 4,20 With transbronchial biopsy, extension of squamous cell carcinoma in situ from the bronchial surface into underlying bronchial glands, with replacement of those glands, may mimic invasive squamous cell carcinoma, and care must be taken to distinguish these two situations (Fig. 6-9) (see Chapter 26). Focal residual glands and identifiable lobular architecture may help in distinguishing glandular involvement with squamous cell carcinoma in situ. Care must be taken not to misinterpret residual or entrapped bronchial glands as adenosquamous carcinoma (Fig. 6-10) (see Chapter 7). Repeat biopsy may be of benefit in making the correct diagnosis. Another potential risk with transbronchial biopsy is that squamous metaplasia within alveolar spaces, in reaction to inflammatory or other disease, may be sampled and may mimic squamous cell carcinoma. Strict adherence to diagnostic criteria will help reduce this risk.2

Tumors that show squamoid features but without single-cell keratinization, squamous pearl formation, or intercellular bridges, should be diagnosed as large cell carcinoma and not as poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.1,2,3 and 4,20 With transbronchial biopsy, extension of squamous cell carcinoma in situ from the bronchial surface into underlying bronchial glands, with replacement of those glands, may mimic invasive squamous cell carcinoma, and care must be taken to distinguish these two situations (Fig. 6-9) (see Chapter 26). Focal residual glands and identifiable lobular architecture may help in distinguishing glandular involvement with squamous cell carcinoma in situ. Care must be taken not to misinterpret residual or entrapped bronchial glands as adenosquamous carcinoma (Fig. 6-10) (see Chapter 7). Repeat biopsy may be of benefit in making the correct diagnosis. Another potential risk with transbronchial biopsy is that squamous metaplasia within alveolar spaces, in reaction to inflammatory or other disease, may be sampled and may mimic squamous cell carcinoma. Strict adherence to diagnostic criteria will help reduce this risk.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree