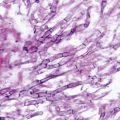

Fig. 20.1

Microscopic view of the mold form of Sporothrix schenckii grown at 25 ℃ on Sabouraud dextrose agar. Note the thin septate hyphae with conidiophores that bear oval conidia that appear “bouquet-like.” (Courtesy of Dr. D. R. Hospenthal)

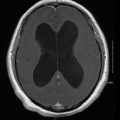

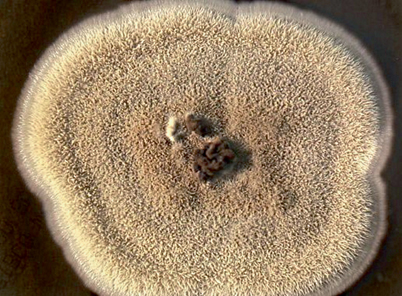

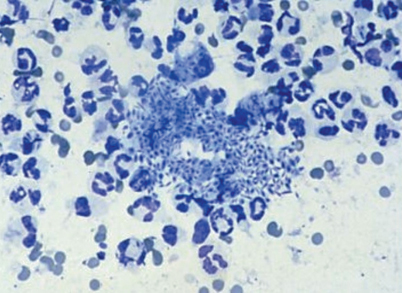

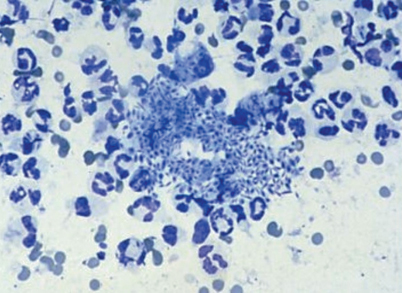

Fig. 20.2

Colony of Sporothrix schenckii grown at 25 ℃ on malt extract agar. Initially cream-colored, the colony darkens over time

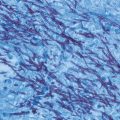

In tissues and in vitro at 37 ℃, S. schenckii assumes a yeast-like form. The yeasts are 4–6 µm in diameter and show budding that can be single or multiple; they are classically described as being cigar-shaped although round and oval forms are also seen (Fig. 20.3). In the laboratory, growth of the yeast phase is accomplished by incubation at 35–37 ºC using enriched media, such as brain heart infusion (BHI) agar. The colony morphology of S. schenckii in the yeast phase is usually off-white and wrinkled. Some strains of S. schenckii do not grow well at 37 ºC but do grow at 35 ºC. These strains are generally found in fixed cutaneous lesions that do not manifest lymphangitic spread [1].

Fig. 20.3

Smear of an ulcerated lesion caused by Sporothrix schenckii showing a large number of oval and cigar-shaped yeasts, 4–6 µm in diameter. (Courtesy of Dr. K. Reed)

In the last decade, molecular studies have made clear the fact that S. schenckii is not a single species but rather a complex of several phylogenetically different organisms [2–5]. Various techniques have been used to differentiate the organisms within the S. schenckii complex [5], creating some confusion for the nonexpert in this area. Currently, it appears that there are at least six species that previously were designated as S. schenckii; these six species demonstrate differences in regard to geography and virulence. S. brasiliensis occurs in Brazil and commonly causes disease in humans and animals, including the large ongoing zoonotic outbreak in Rio de Janeiro [5]. S. schenckii sensu stricto remains an important worldwide human pathogen and is the main species present in North America. S. globosa also is found worldwide, but is reported less frequently as a human pathogen than the above mentioned species [4]. S. mexicana, present in Mexico and other Latin American countries, as well as S. luriei, and S. albicans are uncommon causes of infection in humans.

Note to the reader: Throughout this chapter, the term S. schenckii will be used to refer to the complex of Sporothrix species.

Epidemiology

S. schenckii is found throughout the world. In the environment, S. schenckii is found in sphagnum moss, decaying wood, vegetation, hay, and soil [3]. For infection to occur, one must be exposed to an environmental source, and the organism must be inoculated through the skin. This can occur with motor vehicle accidents, hay baling, landscaping, tree farming, and in developing countries, just the activities of daily living [6–9].

The typical person who develops sporotrichosis is a healthy person whose occupation or hobby takes him or her into the out-of-doors. Classically, landscapers and gardeners develop sporotrichosis because they are exposed to contaminated materials and their activities frequently lead to nicks and cuts on their extremities, allowing easy access for the organism.

Zoonotic transmission can occur from infected animals or from soil transferred from the nails of burrowing animals, such as armadillos [10]. Cats develop ulcerated skin lesions, often on the face, due to sporotrichosis, and many die of the infection. These ulcers are teeming with organisms and are highly infectious [11]. Sporotrichosis also has occurred in laboratory workers who, in the course of handling infected animals or culture material, have inoculated themselves or splashed material into their eye [12].

Outbreaks of sporotrichosis are not uncommon and have been traced back to a variety of point sources: contaminated timbers in a mine, sphagnum moss packed around Christmas trees, bushes, or seedlings, and hay used for Halloween parties [6, 13–15]. The outbreak in Rio de Janeiro associated with transmission from infected cats and affecting mainly housewives and children living in the poorer areas of the city has been ongoing since 1998 and has infected over 2000 persons and many thousands of cats [16–19]. Recent evidence suggests that the strains in this outbreak, which have been identified as S. brasiliensis, are related and likely originated from a common source [17].

Pathogenesis and Immunology

Infection with S. schenckii is almost always initiated when the mold that is present in the environment is inoculated into the skin, usually through minor trauma. Inhalation of the conidia of S. schenckii is the presumed method of transmission in the uncommon syndrome of pulmonary sporotrichosis. Defining virulence factors other than the ability to grow at 37 ℃ is an active area of investigation. Components of the cell wall of S. schenckii, especially a 70-kDa glycoprotein (GP70), mediate adhesion to extracellular matrix and endothelial cell surface proteins, initiating invasion [5]. Extracellular proteinases and melanin are the likely virulence factors [20]. The host response is comprised primarily of neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages, cells able to ingest and kill the yeast phase of S. schenckii [21]. Antibody appears unimportant in immunity, but cell-mediated immunity is crucial in containing infection with S. schenckii [22, 23]. The importance of cell-mediated immunity is supported by the clinical reports of disseminated sporotrichosis occurring in AIDS patients [24, 25], in patients who have hairy cell leukemia [26], in those receiving tumor necrosis factor antagonists [27], and in one patient who had a prior history of lepromatous leprosy [28].

Clinical Manifestations

The usual manifestation of sporotrichosis is localized lymphocutaneous infection. Most patients who present with typical lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis are healthy hosts. Extensive disseminated cutaneous lesions and spread to other structures, including joints, meninges, lungs, and other organs, almost always occur in those who have certain underlying illnesses. Alcoholism and diabetes mellitus are two risk factors for more severe sporotrichosis [29]. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is almost always present in patients who have pulmonary sporotrichosis, and disseminated sporotrichosis is rare unless cell-mediated immunity is suppressed (Table 20.1).

Table 20.1

Clinical manifestations of sporotrichosis

Clinical syndrome | Known risk factors | Initiation of infection |

|---|---|---|

Lymphocutaneous | None | Local inoculation |

Fixed cutaneous | None | Local inoculation |

Osteoarticular | Alcoholism, diabetes | Local inoculation or hematogenous spread |

Pulmonary | COPD, alcoholism | Inhalation |

Meningitis | AIDS | Hematogenous spread |

Other focal disease (eye, breast, larynx, pericardium, epididymis, rectum, spleen, liver) | None known | Hematogenous spread or local inoculation |

Disseminated | AIDS, TNF antagonist therapy, hairy cell leukemia | Hematogenous spread |

Lymphocutaneous Sporotrichosis

The first manifestation of infection generally occurs several days to weeks after cutaneous inoculation of the fungus when a papule appears at the site of inoculation. This primary lesion becomes nodular, and usually will eventually ulcerate. Drainage from the lesion is minimal, is not grossly purulent, and has no odor. Pain is generally mild, and most patients have no systemic symptoms. Over the next few weeks, new nodules that often ulcerate appear proximal to the initial lesion along the lymphatic distribution (Fig. 20.4).

Fig. 20.4

Typical skin lesions in lymphatic distribution seen in a patient who was a horticulturist and had inoculation of Sporothrix schenckii in the subcutaneous tissue of the wrist. From Watanakunakorn (1996). (Reprinted with permission from Oxford University Press)

The differential diagnosis for this form of sporotrichosis includes infection with M. marinum or another atypical mycobacterium, Leishmania species, and Nocardia brasiliensis [30]. Rarely, other bacterial, fungal, and even viral infections cause a similar lymphocutaneous syndrome.

Fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis is uncommon in North America, but common in South America (Fig. 20.5). Patients with this form of sporotrichosis manifest only a single lesion, often on the face, that can be verrucous or ulcerative [8]. The lesion may regress and flare periodically, and can be present for years until it is treated. Pain and drainage are not prominent symptoms.

Fig. 20.5

Fixed cutaneous skin lesion of sporotrichosis. In this form of the disease, lymphatic spread does not occur, and the lesion may remain for months to years until treated. Courtesy of Dr. P. Pappas. From Kauffman (1999). (Reprinted with permission from Oxford University Press)

Pulmonary Sporotrichosis

Pulmonary sporotrichosis is a subacute to chronic illness that usually occurs in patients who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [31–33]. The symptoms mimic those of reactivation tuberculosis. Patients have fever, night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue; dyspnea, cough, purulent sputum, and hemoptysis also occur frequently. Chest radiography shows unilateral or bilateral fibronodular or cavitary disease; the upper lobes are preferentially involved (Fig. 20.6). Sporotrichosis must be differentiated from tuberculosis, chronic cavitary histoplasmosis or blastomycosis, and sarcoidosis. Some, but not all, patients with pulmonary sporotrichosis have disease elsewhere, especially skin and osteoarticular structures.

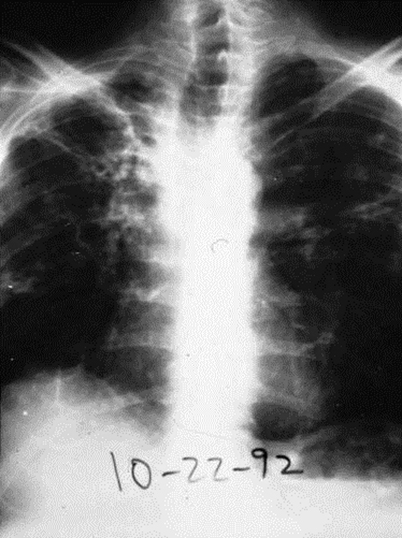

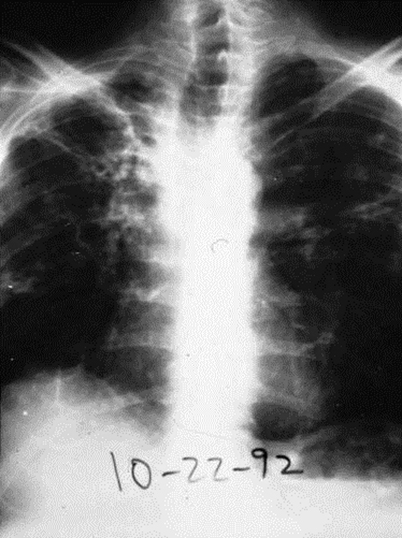

Fig. 20.6

Chest radiograph of a patient with pulmonary sporotrichosis. The patient was an alcoholic who also had diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Osteoarticular Sporotrichosis

Osteoarticular sporotrichosis is an uncommon manifestation of infection with S. schenckii that can occur after local inoculation, but can also arise from hematogenous spread. It is found most often in middle-aged men and appears to occur more frequently in alcoholics. Overlying cutaneous lesions may or may not be present, and one or more joints may be involved. Most commonly, the knees, elbows, wrists, and ankles are infected [34]. Bone involvement usually occurs contiguous to an infected joint (Fig. 20.7). Bursitis and tenosynovitis, the latter presenting as nerve entrapment, also have been described [35].

Fig. 20.7

Elbow X-ray of a patient who had osteoarticular sporotrichosis manifested by infection of both elbows and one knee. There is destruction of the joint and adjacent osteomyelitis of the radius, ulna, and humerus

Meningitis and Disseminated Infection

Meningitis, a rare manifestation of sporotrichosis, occurs almost always in those with cellular immune defects and must be differentiated from tuberculosis or cryptococcosis [24]. Fever and headache are prominent symptoms, and the cerebrospinal fluid findings are those of lymphocytic meningitis with mild hypoglycorrhachia. Meningitis can be an isolated finding, but is usually a manifestation of widespread disseminated infection.

Disseminated sporotrichosis is very uncommon, and may present with fungemia [36]. Almost all patients have had cellular immune deficiencies, and most cases have occurred in persons with AIDS [24–28, 36]. S. schenckii has been reported very rarely to cause infection of eye, larynx, breast, pericardium, spleen, liver, bone marrow, lymph nodes, rectum, and epididymis.

Diagnosis

Culture yielding a Sporothrix species is the gold standard for establishing the diagnosis. Biopsy or material aspirated from a cutaneous lesion should be sent to the laboratory. Sputum, synovial fluid, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid can also yield the organism in patients who have visceral involvement. Material obtained for culture should be inoculated onto Sabouraud’s agar and incubated at room temperature to allow growth of the mold phase of S. schenckii. Growth usually occurs within 1–3 weeks. The characteristic arrangement of conidia on the hyphae makes the diagnosis likely, but conversion to the yeast phase at 35–37 ℃, which may take several additional weeks, allows definitive identification of the organism as belonging to the S. schenckii complex.

The histopathology of sporotrichosis reveals a mixed granulomatous and pyogenic inflammatory process [37]. Caseous necrosis and liquefaction are frequently noted. The organism is an oval to cigar-shaped yeast, 3–5 µm in diameter, and can exhibit multiple buds. However, it is difficult to visualize the organisms within tissues, even with the use of methenamine silver or periodic acid–Schiff stains (see Fig. 4.12, Chap. 4). In some cases, an asteroid body, in which the basophilic yeast is surrounded by eosinophilic material radiating outward like spokes on a wheel, can be seen [38]. This is also known as the Splendore–Hoeppli phenomenon and is not specific for sporotrichosis, but can be seen in various parasitic, fungal, and bacterial infections. This reaction is thought to be due to deposition of antigen–antibody complexes around the organism in tissues.

Studies have been ongoing for many years to develop an enzyme immunoassay, but currently there are no commercially available serological assays to aid in the diagnosis of sporotrichosis. A nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay using primers binding to specific sequences of the 18s rRNA gene of S. schenckii has been used to identify Sporothrix species in tissue samples [39], and others have used PCR to detect DNA from Sporothrix species in tissue samples [40]. However, PCR assays are available only through reference laboratories at the present time.

Treatment

In general, most patients who have sporotrichosis are treated with oral azole antifungal agents. Those patients who have disseminated infection, meningitis, or severe pulmonary involvement are treated initially with intravenous amphotericin B. Guidelines for the management of the various forms of sporotrichosis were published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America [41], and the suggestions that follow are modified from these guidelines (Table 20.2).

Table 20.2

Treatment of sporotrichosis

Clinical syndrome

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|