Fig. 18.1

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of yeast in macrophages

Epidemiology

Histoplasmosis is most commonly reported to occur in and around the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys of the USA, in South and Central America [3, 4] and less so in parts of Africa and Asia. This is thought to be due to factors such as the climate, humidity, and soil acidity. Large amounts of bird and bat excreta enrich the soil in which the fungi are found, facilitating growth, and accelerating sporulation. When disturbed, microfoci or niches harboring a large number of infective particles may lead to high infectivity rates or large outbreaks. In most cases, however, the exposure is small and infection is usually unrecognized. Cases outside the endemic area usually occur in individuals who have traveled or previously lived in endemic area(s) [5]. However, microfoci containing the organism can sometimes be found outside the endemic area and may be the source for exposure.

Pathogenesis and Immunology

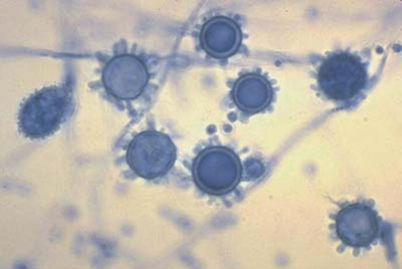

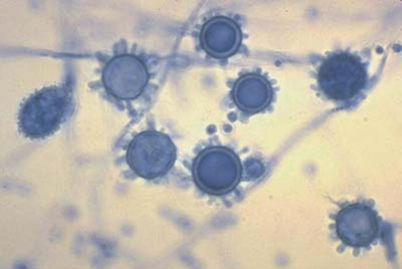

Infection occurs when aerosolized microconidia (spores) are inhaled (Fig. 18.2). Infection usually is asymptomatic in healthy individuals following low-level exposure. Infection usually is self-limited except following heavy exposure or in patients with underlying diseases that impair immunity. Pulmonary infection may be progressive in patients with underlying obstructive lung disease. For unknown reasons, pulmonary infection may rarely elicit exuberant mediastinal fibrosis.

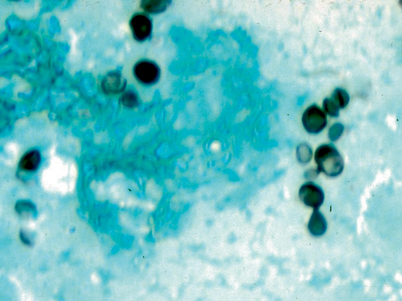

Fig. 18.2

Lactophenol cotton blue stain of the mold grown at 25°C. Note microconidia and tuberculate macroconidia

Phagocytic cells including macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells are rapidly recruited to the alveolar spaces that contain conidia [6]. Within a few days, the conidia transform into yeast, which multiply within the nonactivated macrophages, and disseminate via the bloodstream to extrapulmonary organs. Neutrophils and dendritic cells inhibit proliferation of the organism, and dendritic cells present antigen to T lymphocytes as the initial step in development of specific cell-mediated immunity. Consequently, tumor necrosis factor alpha and interferon gamma are induced, which activate macrophages to inhibit the growth of the organism, leading to spontaneous recovery and immunity against reinfection in most individuals [7]. Traditionally, humoral immunity is not felt to be important, but recent studies using monoclonal antibodies against specific Histoplasma epitopes suggest a protective role for humoral immune response.

Reactivation of latent infection has been proposed as the mechanism for progressive disseminated histoplasmosis (PDH) in immunocompromised patients. However, the rarity of PDH in immunosuppressed patients (0.1–1 %) argues against reactivation as a common mechanism of pathogenesis. Histoplasmosis occurs in about 0.5 % of patients undergoing solid organ transplantation in endemic areas [8]. Among 469 patients treated with TNF inhibitors for inflammatory bowel disease at a single institution, 3 (0.6 %) developed histoplasmosis [9].

More likely, PDH in immunosuppressed individuals occurs because low-grade histoplasmosis was present at the time immunosuppression was initiated, or infection was acquired exogenously. In endemic areas, repeated exposure to Histoplasma spores probably occurs, permitting reinfection in immunosuppressed individuals whose immunity to H. capsulatum has waned.

Clinical Manifestations

Asymptomatic Infection

Infection is asymptomatic in most otherwise healthy individuals, who experience low inoculum exposure, as indicated by skin test positivity rates above 50–80 % in endemic areas [10]. Asymptomatic infection also may be identified by radiographic findings of pulmonary nodules or mediastinal lymphadenopathy, which eventually calcify, by splenic calcifications, or by positive serologic tests performed during screening for organ or bone marrow transplantation or epidemiologic investigation. In endemic areas, about 5 % of the healthy subjects have positive complement fixation tests for anti-Histoplasma antibodies.

Acute Pulmonary Histoplasmosis

Healthy individuals who experience a heavy exposure usually present with acute diffuse pulmonary disease one to two weeks following exposure. Fever, dyspnea, and weight loss are common, and physical examination may demonstrate hepatomegaly or splenomegaly as evidence of extrapulmonary dissemination. In many cases following heavy exposure, the illness is sufficiently severe to require hospitalization, with some individuals experiencing respiratory failure. Chest radiographs usually show diffuse infiltrates, which may be described as reticulonodular or miliary (Fig. 18.3).

Fig. 18.3

Chest radiograph showing diffuse infiltrate seen in acute pulmonary or disseminated histoplasmosis

Subacute Pulmonary Histoplasmosis

In symptomatic cases, the most common syndrome is a subacute pulmonary infection manifested by respiratory complaints and fever lasting for several weeks, then resolving spontaneously over 1 or 2 months. The chest radiograph or CT scan usually shows focal infiltrates with enlarged mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy (Fig. 18.4). Symptoms caused by a mediastinal adenopathy may prevail, and in some cases persist for months to years (granulomatous mediastinitis). In some cases, respiratory symptoms may be mild or absent, and findings of pericarditis or arthritis/arthralgias may be prominent. Pericarditis and this rheumatologic syndrome represent inflammatory reactions to the acute infection, rather than infection of the pericardium or joints.

Fig. 18.4

Chest radiograph showing hilar lymphadenopathy seen in subacute pulmonary histoplasmosis

Chronic Pulmonary Histoplasmosis

Patients with underlying obstructive pulmonary disease develop chronic pulmonary disease following infection with H. capsulatum. The underlying lung disease prevents spontaneous resolution of the infection. Chest radiographs reveal upper lobe infiltrates with cavitation, often misdiagnosed as tuberculosis (Fig. 18.5). The course is chronic and gradually progressive, highlighted by systemic complaints of fever and sweats, associated with shortness of breath, chest pain, cough, sputum production, and occasional hemoptysis. Patients often experience repeated bacterial respiratory tract infections, and occasionally superinfection with mycobacteria or Aspergillus.

Fig. 18.5

Chest radiograph showing upper lobe infiltrates with cavitation seen in chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis

Progressive Disseminated Histoplasmosis (PDH)

Hematogenous dissemination is common during acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, but is nonprogressive [11]. With the development of specific cell-mediated immunity, the infection resolves in the lung and extrapulmonary tissues. In contrast, disease is progressive in individuals with defective cell-mediated immunity. In many cases, the cause for immune deficiency is easily identified, and often includes the extremes of age, solid organ transplantation [12], treatment with immunosuppressive medications [13], acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [14], idiopathic CD4+ leucopenia [15], deficiency in the interferon-γ/interleukin-12 pathway [16], or malignancy [17]. In other cases, the cause for immunodeficiency remains unknown, awaiting a more complete understanding of immunity in histoplasmosis and development of better tests for diagnosis of immunodeficiency.

Clinical findings in PDH include fever and progressive weight loss, often associated with hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, and laboratory abnormalities including anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, liver enzyme elevation, and ferritin elevation [11]. An elevation in serum lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) has been associated with disseminated histoplasmosis, particularly levels greater than 600 IU/L. Pulmonary involvement is often the prominent feature in PDH, with manifestation as severe as respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation and vasopressor support for shock. The classical radiographic finding in PDH is diffuse reticulonodular infiltrates on chest X-ray and CT scan. Other less frequent sites of involvement include the central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, skin, and adrenal glands. PDH also may present as culture-negative endocarditis, accompanied by other sites of dissemination or as an isolated manifestation of histoplasmosis [18].

Fibrosing Mediastinitis and Mediastinal Granuloma

Fibrosing mediastinitis is a rare complication of pulmonary histoplasmosis [10]. The mechanism for this manifestation appears to be an excessive fibrotic response to antigens released into the mediastinal tissues rather than progressive infection. It is unclear why the immune response from subclinical histoplasmosis can lead to either mediastinal granuloma formation (with inflammation and caseating necrosis) or this fibrotic process. Genetic influences, inoculum size, and host immunity are all likely factors. The clinical findings of fibrosing mediastinitis are caused by obstruction of mediastinal structures and may include involvement of the superior vena cava, airways, or pulmonary vessels. Infiltrative inflammatory mediastinal masses that do not respect fat or fascial planes are characteristic computed tomography findings of fibrosing mediastinitis. Fibrosing mediastinitis most commonly involves the right hemithorax, although bilateral involvement may occur. In most patients, obstruction does not progress, but mild to moderate symptoms persist indefinitely. In less than one quarter of patients, the illness is progressive, highlighted by repeated bouts of pneumonia, hemoptysis, respiratory failure, or pulmonary hypertension. No proven medical therapy exists for fibrosing mediastinitis due to histoplasmosis, including antifungal or corticosteroid therapy. Since the pathogenesis involves fibrosis rather than inflammation or infection, antifungal or anti-inflammatory therapy is not effective. Because fibrosis infiltrates adjacent mediastinal structures, surgical therapy has been of little benefit and is associated with a high risk for surgical morbidity and mortality. Surgical therapy is a rarely indicated, and should be considered only after careful consideration of the risks and benefits by experts in the management of patients with fibrosing mediastinitis. Various procedures to relieve compression of vascular structures, and airway and esophageal compression are often employed with mixed results.

Distinguishing fibrosing mediastinitis from mediastinal granuloma is the key. Mediastinal granuloma represents persistent inflammation in mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes. Enlarged, inflamed notes may cause chest pain with or without impingement upon soft mediastinal structures, such as the esophagus or superior vena cava. Fistulae may develop between the lymph nodes, airways, or esophagus. Improvement may occur spontaneously or following antifungal therapy. The enlarged lymph nodes are usually encased in a discrete capsule, which can be dissected free from the adjacent tissues with a low risk for surgical morbidity or mortality. Thus, surgery may be appropriate in patients with persistent symptoms despite antifungal therapy, weighing the risk of surgery with the severity of the clinical findings. However, studies establishing the effectiveness of surgery for mediastinal granuloma are scant, and surgical therapy is rarely necessary in such cases.

Often mediastinal lymphadenopathy is asymptomatic, identified on chest radiograms or CT scans performed for other reasons. In such cases, concern often arises as to whether the mass represents malignancy. Differentiation of mediastinal lymphadenopathy caused by histoplasmosis or other granulomatous infection from that caused by a malignancy is best deferred to pulmonary disease consultants [10]. The presence of calcification strongly suggests that lymphadenopathy is caused by granulomatous infection, but cannot rule out concomitant neoplasm. Conversely, the absence of calcification does not exclude granulomatous infection, and is quite typical of histoplasmosis during the first year or two after infection. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan has been suggested as a method to distinguish malignancy from nonmalignant causes for mediastinal or pulmonary masses, but PET scan is often positive in patients with histoplasmosis. For most patients lacking risk factors for malignancy, follow-up CT scans at 3–6 month intervals for 1 year is appropriate, lack of progressive enlargement supporting the diagnosis of histoplasmosis. In others, especially those with risk factors for malignancy, biopsy may be necessary for definitive diagnosis. Choices include surgical excision or mediastinoscopy, although many recommend avoiding the latter due to risk of excessive bleeding.

African Histoplasmosis

In addition to infection with Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum, Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii causes disease in Africa. Bony abscesses, more commonly involving the axillary skeleton and skin lesions are much more common with African histoplasmosis. Pulmonary disease is rare, although infection with this variant also likely occurs via inhalation of spores. Disseminated African histoplasmosis resembling PDH as described above has been reported, with fever, multiorgan involvement, and a progressive course. The yeasts of H. capsulatum var. duboisii are 10–15 µm in diameter (much larger than var. capsulatum) and can be seen within giant cells. This can be easily confused with Blastomyces dermatitis or Coccidioides immitis on histopathological examination. DNA and antigen tests with the African variant should react similarly to H. capsulatum var. capsulatum. Likewise, therapy is similar with the exception that isolated cutaneous disease, or “cold abscesses” may heal spontaneously or with excisional surgery. Disseminated African histoplasmosis, especially with HIV coinfection, has a poor prognosis.

Diagnosis

Culture

The only test specific for histoplasmosis is culture, but the sensitivity is low, and delays up to 1 month may be required to isolate the organism [15]. Identification of H. capsulatum can be determined by conversion from the mold to the yeast, exoantigen detection, or through use of the commercially available DNA probe. Despite these limitations, culture should be performed unless the patient is already improving at the time diagnosis is suspected. In patients with pulmonary disease, bronchoscopy may be required if patients are unable to produce sputum. In those with suspected PDH, fungal blood cultures should be obtained, but cultures of tissues requiring invasive procedures may be deferred if tests for antigen are positive. In such cases, failure to improve within 2 weeks after initiation of therapy would raise question about the diagnosis and support additional testing.

Antigen Detection

Antigen detection is the most useful method for rapid diagnosis of the more severe histoplasmosis syndromes, including acute diffuse pulmonary histoplasmosis and PDH [19, 20]. Antigen may be detected in any body fluid, but urine and serum testing is recommended in all cases. In some patients with pulmonary histoplasmosis, antigen may be detected in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid but not in urine or serum [21]. Antigens may also be detected in the cerebral spinal fluid in patients with central nervous system histoplasmosis [22]; in pleural fluid, synovial fluid, peritoneal fluid, or pericardial fluid in patients with infection localized to those tissues. Antigen levels decline with effective therapy [23], persist with ineffective therapy, and rebound in patients who relapse during or following treatment [24].

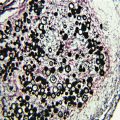

Histopathology

Demonstration of yeast-like structures in body fluids or tissues may provide a rapid diagnosis in some cases [10] (Fig. 18.6; also see Fig. 4.8 and 4.8, Chap. 4). Limitations of histopathology include the need for performance of an invasive procedure and low sensitivity. Histopathology may be falsely negative or falsely positive when performed by pathologists inexperienced with recognition of fungal pathogens. If histopathology is inconsistent with clinical findings or other laboratory tests, the specimens should be reviewed by a pathologist experienced with recognition of fungal pathogens.