Abstract

Spinal tumors are classically grouped into three categories, extradural tumors, intradural extramedullary tumors, and intradural intramedullary tumors. Spinal tumors may cause spinal cord compression and vascular compromise, resulting in pain or neurologic compromise. They may also alter the architecture of the spinal column, resulting in spinal instability. Oncologic management of spinal tumors varies according to the stability of the spine, presence of pain, and neurologic status. Management options include surgical intervention, radiation therapy, and systemic treatments such as hormonal therapy and chemotherapy.

Keywords

Chemotherapy, Radiation therapy, Spinal cord compression, Spinal tumors

Introduction

Spinal tumors or their treatments may directly or indirectly cause neurologic impairments that affect the physical, social, vocational, and emotional capabilities of an individual and their caregivers. The available treatment options for these tumors continue to improve and bring with them improved patient survival. This has made it more important than ever for clinicians to be aware of the potential long-term neurologic impact of these potentially devastating disorders.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Spinal tumors are classically grouped into three categories, extradural tumors, intradural extramedullary tumors, and intradural intramedullary tumors. These tumors may be primary or secondary to metastatic disease. Primary tumors account for a relatively small percentage of all spinal tumors and generally occupy the intradural spaces, whereas metastatic disease tends to be extradural in nature.

Extradural Tumors

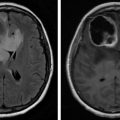

Extradural (epidural) tumors refer to lesions outside of the dura mater, in the vertebral bodies and neural arches ( Fig. 8.1 ). These tumors are more commonly malignant than benign. Primary tumors may arise from osteoblasts, chondrocytes, fibroblasts, and hematopoietic cells. Benign tumors include vertebral hemangiomas, giant cell tumors, osteochondromas, osteoid osteomas, and osteoblastomas. Primary malignant tumors include lymphoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, chordoma, sacrococcygeal teratoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, solitary plasmacytoma, and fibrosarcoma.

Metastatic disease is far more common in the extradural space, with up to a 70% prevalence in patients with cancer. Solid tumors such as lung, breast, and prostate cancers are the most common sources of metastases. Renal cell carcinoma, thyroid cancer, and colon cancer are also relatively common. Among hematologic tumors, non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common. The majority of metastases reaches the spine through hematogenous spread. Direct extension of primary tumors may also occur. For instance, prostate, bladder, and colorectal cancers may become locally aggressive and invade the lumbar or sacral regions of the spine.

Primary and metastatic extradural tumors may be osteolytic, osteoblastic, or mixed in nature. Osteolytic lesions result in bone destruction greater than bone formation, whereas osteoblastic lesions result in bone deposition without breakdown of old bone first. Osteolytic lesions are more common in adults and seen with breast, lung, and thyroid cancers. Prostate and bladder cancers and carcinoid tumors are typically osteoblastic in nature. Mixed lytic/blastic lesions can be seen with lung, breast, cervical, and ovarian cancers.

Both osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions alter normal bone architecture, potentially resulting in deformity or collapse of the affected vertebral body. This deformity or collapse may lead to spinal instability by increasing strain on the support elements of the spine, including muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules. Spinal instability can result in spinal cord compression from retropulsion of bone fragments into the epidural space.

Extradural lesions may grow into the epidural space, resulting in mechanical injury to the axons and myelin of the spinal cord. Growth into the epidural space may also cause vascular compromise of the spinal arteries and epidural venous plexus, resulting in cord ischemia and/or infarction.

Depending on the underlying malignancy, 2%–5% of patients will develop clinical signs and symptoms of epidural spinal cord compression (ESCC) during the course of their disease. Adults with myeloma and prostate cancer have the highest risk of developing ESCC (7.9% and 7.2%, respectively). In the pediatric population, sarcoma and neuroblastoma are the most common malignancies resulting in ESCC. Symptomatic lesions are most often diagnosed in the thoracic region, presenting as incomplete paraplegia; although cadaveric studies have shown the most common site of tumor burden is in the lumbar spine.

Intradural Extramedullary Tumors

Intradural extramedullary tumors ( Fig. 8.2 ) are located within the dura mater but outside the spinal cord parenchyma. These tumors are most commonly benign and can be seen in all regions of the spine. Primary intradural extramedullary tumors arise from peripheral nerves, nerve sheaths, and sympathetic ganglion. Benign tumors include meningioma, schwannoma, neurofibroma, paraganglioma, and ganglioneuroma. Malignant primary tumors include malignant nerve sheath tumors and hemangiopericytoma.

Extramedullary metastases, or leptomeningeal disease (LMD), are a relatively common complication of cancer, occurring in 3%–8% of all patients. Metastatic disease is thought to reach the leptomeninges through hematogenous spread, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) seeding, or direct extension. CSF seeding can occur spontaneously or as a by-product of surgical intervention. Direct extension can occur along the epineurium or perineurium of spinal nerves, particularly from paravertebral metastases. It can also occur along veins exiting vertebral body bone marrow. 3,6 Glioblastoma, central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma, leukemia, lymphoma, breast cancer, lung cancer, and melanoma are common sources of LMD. The most common site of leptomeningeal involvement is the dorsal aspect of the spinal cord, particularly at the cauda equina.

Similar to extradural lesions, LMD can result in spinal cord compression and vascular compromise. Vascular compromise in this setting can result in ischemia and spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage. The risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage is greatest in patients undergoing treatment with anticoagulants.

Intradural Intramedullary Tumors

Primary intradural intramedullary tumors account for 4%–5% of all primary CNS tumors. They are located within the spinal cord parenchyma and arise from glial cells, neuronal cells, and other connective tissue cells. Intramedullary tumors are classified as low, intermediate, or high grade based on cytology. Ependymomas are the most common primary intramedullary tumors in adults and are most often located in the filum terminale and conus medullaris. Astrocytomas are the most common in children and can be located in any region of the spinal cord. Other primary intramedullary tumors include hemangioblastoma, cavernous angioma, ganglioglioma, neurocytic tumors, oligodendroglioma, and embryonal neoplasms.

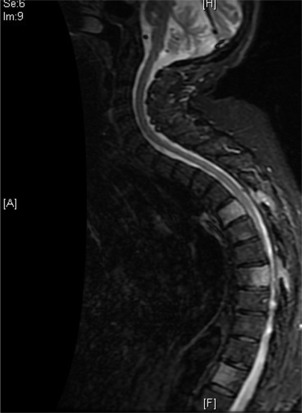

Intramedullary spinal cord metastases usually occur in the setting of extensive metastatic disease and are diagnosed in less than 1% of patients with cancer ( Fig. 8.3 ). Metastatic disease occurs either by hematogenous spread or via the leptomeninges, along nerve roots or through the Virchow-Robin spaces. These lesions can be seen throughout the spinal cord, usually as a solitary lesion. The most common segment involved is the vascular-rich cervical spinal cord.

Lung and breast cancers, melanoma, lymphoma, and renal cell carcinoma can result in intramedullary metastases. Half of all instances are the result of small-cell lung cancer. A majority of patients with intramedullary lesions have concomitant brain metastases and up to 1/4 have known LMD.(HAMMACK) Intramedullary metastases may result in neurologic injury, through direct compression to the surrounding spinal cord and vascular structures.

Clinical Manifestations

Extradural Tumors

Pain is the most common initial presenting symptom in patients with ESCC (80%–90% of cases) and may precede the development of neurologic symptoms by weeks to months. Individuals with extradural involvement classically describe three types of pain, local, mechanical, and/or radicular pain. An individual with epidural involvement may experience one or more of these pain syndromes.

Localized pain, described as a deep “gnawing” or “aching” pain, is thought to be the result of periosteal stretching and inflammation caused by tumor growth. It is often nocturnal in timing and improves with activity and antiinflammatory medications. Percussion or palpation over involved spinous processes may elicit tenderness in individuals with this type of pain.

Unlike localized pain, mechanical pain varies with position or activity and is often refractory to antiinflammatory and pain medications. Mechanical pain characteristically occurs with transitional movements or axial loading of the spine. Alternatively, it may be elicited by lying prone or supine, particularly with thoracic spine involvement. This pain is concerning as it is often indicative of impending or established spinal instability. Mechanical pain responds well to stabilization of the spine with bracing or surgical fixation.

Radicular pain occurs in the setting of nerve root compression either from tumor extension into the neuroforamen or with pathologic fractures that obliterate this space. It is often described as sharp, shooting, or stabbing in nature. With cervical or lumbar lesions, radicular pain is usually unilateral, radiating to the upper or lower extremity, respectively. In the thoracic region, radicular symptoms can be bilateral and are described as a bandlike sensation around the chest or abdomen.

Motor weakness is the next most common presenting symptom of epidural cord compression (35%–85% of cases). Similar to traumatic injuries, patterns and distribution of weakness is dependent on the region of cord involvement. Patients with cervical involvement may have a lower motor neuron pattern of weakness in the upper extremities and upper motor neuron pattern in the lower extremities. Thoracic lesions may result in upper motor neuron findings in the lower extremities, with flexor musculature weaker than extensor. Lumbosacral involvement affects the lower extremities in a lower motor neuron pattern.

Sensory impairments are rarely the initially reported symptom of epidural cord compression but are usually present at the time of diagnosis. Similar to motor weakness, the distribution of sensory impairments is dependent on the location of nerve root or spinal cord involvement.

Nerve root compression may result in a dermatomal distribution of paresthesias. Compression of the dorsal columns may result in loss of conscious proprioception, vibration and light touch from the ipsilateral body, and information about visceral distension. Individuals may report an ascending pattern of tingling and numbness or a sensation of tightness about the trunk or limb. They may experience ataxia and balance impairments as a result of proprioception loss. Lhermitte’s phenomenon, an electric shock sensation that extends into the back and sometimes limbs with changes in neck or head position, can be seen with cervical and upper thoracic dorsal column involvement.

Involvement of the lateral spinothalamic tracts results in a loss of pain and temperature perception one or two dermatomes below the level of injury, on the contralateral side of the body. Spinothalamic involvement rarely causes paresthesias.

Autonomic symptoms are unusual as an initial symptom but can be present with epidural cord compression. These symptoms usually correlate with the degree of motor involvement and may include bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction, loss of sweating below the level of compression, and orthostatic hypotension.

Gait and truncal ataxia may occur with compression of the spinocerebellar tracts. Spinocerebellar involvement can be differentiated from cerebellar involvement by the absence of upper extremity ataxia, dysarthria, and nystagmus.

Other clinical findings of epidural cord compression may include the eruption of herpetic zoster at the level of cord involvement, Horner’s syndrome (C7-T1 involvement), and neuropathic facial pain (high cervical lesions with involvement of the descending fibers of the trigeminal-thalamic tract).

Intradural Extramedullary Tumors

Patterns of spinal cord injury from extramedullary tumors are similar to those from epidural lesions. Approximately 70%–90% of individuals present with pain as the initial symptoms of cord involvement. This pain is often axial and/or radicular in nature and is worsened in recumbent positions. There is however a higher rate of neurologic impairment with extramedullary involvement. In addition, neurologic impairments may occur in the absence of pain. More than 60% of individuals referred for surgical resection of LMD have some degree of weakness.

Almost all patients with extramedullary cord involvement have some degree of sensory impairments. Bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction are also common (30%–80% of cases) and tend to be an early finding. The constellation of symptoms with extramedullary cord compression may resemble those of Brown-Séquard, conus medullaris, or cauda equina injuries.

Intramedullary Tumors

Intramedullary tumors may also present with surprisingly similar symptoms to their epidural counterparts. Pain, the most common initial symptom (30%–85% of cases), is often described as a dull/aching posterior midline pain, paravertebral stiffness/tightness, or radiculopathy. (KIM) Neurologic impairments are also common and typically involve cord segments below the level of tumor involvement. More than 92% of patients with intramedullary tumors have some degree of weakness, 62%–87% sensory deficits and approximately 70% have bowel and/or bladder dysfunction on examination.

Similar to extramedullary cord compression, intramedullary lesions may resemble Brown-Séquard, conus medullaris, and cauda equina syndromes. In addition, they may present with central cordlike findings and Horner’s syndrome.

Spinal Instability

Spinal instability is defined as a loss of spinal integrity as a result of a neoplastic process. Instability is associated with movement-related (mechanical) pain, symptomatic and progressive spinal column deformity, and/or neurologic compromise under a normal physiologic load. Factors considered by treating teams when evaluating the structural stability of the spinal column include presence of mechanical pain, location of the tumor, alignment of involved spinal segments, extent of vertebral body involvement, presence of posterior element involvement, bone lesion quality, and overall bone mineral density.

The presence of multiple contiguous or noncontiguous lesions, loss of intervertebral disc integrity, facet joint arthropathy, prior surgical interventions, and treatments such as radiation therapy and hormonal therapies may also influence the risk for spinal instability. There are various scoring scales available to assess spinal stability in the cancer population. Any concern about potential instability warrants a surgical referral.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree