Hugh Spear Pemberton [2]. (By courtesy of the University of Liverpool Library)

Hugh Spear Pemberton was born on June 3, 1890, in Liverpool, England, the youngest son of Thomas Shepherd Pemberton and Elizabeth Marion [1]. He attended the Liverpool Institute and Liverpool University and graduated in 1913 with first class honors with M.B. and Ch.B. degrees. In the fall of 1913 after obtaining his qualifying medical degrees, he became a resident physician and joined the staff at the David Lewis Northern Hospital in Liverpool where he worked for his entire career. Dr. Pemberton married Sarah Ann Hanley in 1914 and his daughter, Lesley Mary, was born in 1916 [2].

His tenure at the David Lewis Northern Hospital was interrupted by World War I, in which he served in the Royal Army Medical Corps in France and Russia. He returned to the David Lewis Northern Hospital in 1918 and was appointed junior physician. He became a member of the Royal College of Physicians in 1921 and achieved the rank of senior consultant at the David Lewis Northern Hospital in 1924.

Dr. Pemberton was a lecturer in clinical medicine at Liverpool University and was recognized for his skills as a teacher. In addition to the Northern Hospital, he also worked at Liverpool Hospital for Women, the Liverpool Radium Institute and the Neston, Hoylake and West Kirby Cottage Hospitals. He became a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in 1941. He was chairman of the Birkenhead and Wirral Division of the British Medical Association from 1946 to 1950 and vice president of the Section of Medicine in 1950.

Dr. Pemberton had special interests in diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, thyroid disease, and hospital planning, publishing several papers in the British Medical Journal over the course of his career. In 1922, he founded a diabetes clinic, thought to be the first of its kind in England, at the David Lewis Northern Hospital. He also helped found the peripheral vascular disease clinic at the Northern Hospital. He was the principal author of the Northern Hospital’s diet book, first published in 1935. He was actively involved with the diagnosis and management of diabetic patients with peripheral vascular disease.

Dr. Pemberton was a dedicated clinician who worked long hours at the hospital and rarely took a day off. He was meticulous, paying close attention to detail and staying late to care for his patients. He was an outstanding teacher who enjoyed discussing medicine with younger colleagues and students. They enjoyed learning from him so much that it became competitive to obtain a position on his team, which was affectionately known as “Pem’s firm” [3]. His devotion to the Northern Hospital was especially evident during World War II when he organized and led the evacuation of patients to a local collegiate institution.

Hugh Spear Pemberton was the first to describe an important physical examination finding in patients with substernal goiter that would later become known as Pemberton’s sign . In a short letter published in the October 5, 1946, issue of The Lancet, Pemberton wrote, “There is a useful sign given by a submerged or intrathoracic goiter which I have employed and taught for many years. It consists in getting the patient to elevate both arms until they touch the sides of the head; after a moment or so, congestion of the face, some cyanosis, and lastly distress become apparent—presumably from narrowing of the thoracic inlet and obstruction of the venous return. I have not seen it in superior mediastinal block. Doubtless the sign has been described before and even bears a name, but I am unaware of it” [4] (Fig. 1). This finding was subsequently termed Pemberton’s sign and has been widely referred to ever since its first description.

Fig. 1

A patient with a positive Pemberton sign. (Reprinted with permission from Dr. Bill Fleming)

Pemberton’s wife died in 1950 and he married Dorothy Alice Parker in 1951. He continued to work as a senior physician at the Northern Hospital until his mandatory retirement in June 1955 at the age of 65. He died in his home in Neston, Cheshire less than 6 months after his retirement on January 15, 1956, at the age of 65.

The Superior Thoracic Aperture

Pemberton’s sign is a manifestation of impingement on the already limited space in the superior thoracic aperture. The superior thoracic aperture is bounded anteriorly by the sternum, posteriorly by the upper border of the first thoracic vertebra (T1), and laterally by the first ribs [5]. It is approximately 5 cm in anteroposterior diameter (manubrium to T1) and 10 cm in width (rib to rib). The superior aperture can be divided into right lateral, left lateral, and medial compartments. The lateral compartments contain the apices of the lung and pleura, the brachial plexus, and vasculature of the upper extremities. The medial area contains the trachea, esophagus, the sympathetic trunk, the vagus, recurrent laryngeal and phrenic nerves, the vertebral and common carotid arteries, and the internal jugular and inferior thyroid veins.

Substernal Goiters

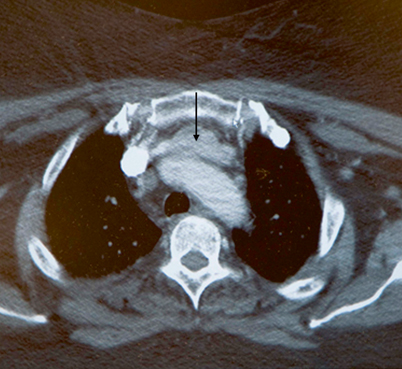

The term substernal goiter has traditionally been used to describe thyroid enlargement with at least 50 % of the thyroid tissue extending below the superior thoracic aperture [6–9] (Fig. 2) . However, patients may experience compressive symptoms related to impingement on vital structures from a retrosternal component that is less than 50 % of the total thyroid mass. As a result, a more liberal definition is often used, consisting of an estimated 3 cm of thyroid tissue below the sternal notch when the patient’s neck is extended [10]. The normal swallowing mechanism, the negative intrathoracic pressure, and the force of gravity are factors that are felt to contribute to the development of a substernal goiter [11].