CHAPTER 25 Skin Problems

Introduction

There is a remarkable paucity in the medical literature concerning skin problems in immigrants from developing countries compared with those born in industrialized nations. One of the few reviews of immigrant dermatological problems was carried out in the late 1980s by five European hospital-based dermatology clinics, one each in the Netherlands and Germany, and three in the UK.1 In the Dutch clinic, the top diagnoses among im-migrants, mostly from Surinam, Turkey, Indonesia, Morocco, and the Caribbean, were contact dermatitis, alopecia, dermatophytosis, psoriaisis, herpes simplex, vitiligo and pityriasis versicolor. In hospitalized patients in Germany, made up mostly of Turks and Yugoslavs, idiopathic urticaria and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) were the primary diagnoses. In a South London clinic, made up mostly of Afro-Caribbeans, the major disorders were those of pigmentation and hair. Curly hair was associated with folliculitis of the scalp, ingrown hairs of the beard, abscess formation, and keloid scarring. Traction alopecia was seen with changes in hair fashion. On the other hand, in the Asian population of South London, eczema, warts, dermatomycosis, and acne were the primary presenting diagnoses and were similar to the non-immigrant population. The middle-class Asian population reviewed in Leicester, England, were most likely to complain of pigmentary disorders (vitiligo, postinflammatory pigmentary alterations, and facial hyperpigmentation), idiopathic pruritus, and atopic eczema, compared with the non-Asian population. Among both Asian populations surveyed, there was considerable social stigma attached to vitiligo and other skin conditions that leave visible marks, especially those found in young women (Table 25.1).

Although dermatological problems among newly arrived immigrants are not well documented, several reviews have focused on skin problems in ethnic communities of which the majority would be immigrants.2 A survey of 75 589 patients seen over 2 years at the National Skin Centre in Singapore documented the spectrum of disease in its Asian population.3 The majority of its patients were Chinese with 5–10 % each of Indian, Malay, and others. The 11 most common diagnoses were: dermatitis (34.1%), acne (10.9%), viral infections (5.7%), fungal infections (5.4%), urticaria (4.7%), contact dermatitis (4.0%), psoriasis (3.3%,) bacterial infection (3.0%), alopecia (2.4%), nonvenomous insect bites (2.3%), and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (1.9%).

Sanchez recently reported his findings on dermatological problems in 2000 Latinos in a large hospital based clinic.4 The top 10 diagnoses included: eczema/ contact dermatitis (20.1%), condyloma/warts (17.5%), acne (12.3%), tinea/onychomycosis (9.3%), pyoderma (8.8%), hyperpigmentation (7.5%), seborrheic dermatitis (7.2%), psoriaisis (5.5%), facial melasma (4.1%), and pruritus (2.3%).

In a recent study from France of 622 ill returned travelers, dermatological problems were the most frequent reason for consultation, making up 23.4% of all the medical conditions found in these travelers.5 Immigrants accounted for one-third of the 149 travelers with skin problems, only slightly less than tourists.

Physical Examination

Unlike many other aspects of infectious disease, where the history is the most important element in diagnosis, the physical examination is paramount in those presenting with a skin problem. One of the cardinal rules of the physical examination involving a dermatological complaint is that the physical examination must be complete and comprise all areas of skin, including the breasts, buttocks, and scalp. In patients with suspected leprosy, superficial cutaneous nerves must be examined as well (see Ch. 34). For some immigrant populations, it might be necessary for a different examiner of the same gender as the patient to carry out the examination in order to examine the skin thoroughly.

Laboratory Investigations (General Principles)

Laboratory investigations may be non-specific, such as a complete blood count, or specific, such as disease serology or biopsy and culture of a lesion. It is important to understand that alterations in the white blood count, such as eosinophilia, may or may not be related to the clinical problem under investigation (see Ch. 21). Not infrequently, immigrants from developing countries have eosinophilia due to a cryptic helminth infection; therefore, eosinophilia in the presence of skin lesion may be completely unrelated to the clinical problem. Along the same lines, serological tests for infectious diseases, particularly when the disease is chronic, cannot distinguish between an active infection and one that has been treated and cured. For example, a patient who has leishmania antibodies and a skin ulcer may not have active cutaneous leishmaniasis but rather evidence of a previous, silent infection.

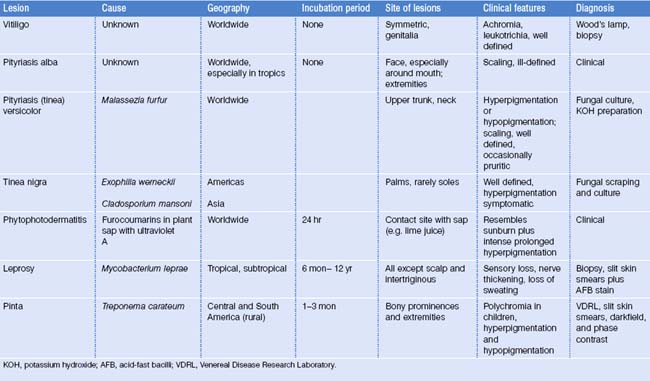

It would be impossible for one to cover all of the possible infectious skin disorders found in immigrants and refugees. Febrile illnesses associated with rash have been covered in the tabular approach to differential diagnosis. In this chapter, cutaneous infectious diseases that are most common among immigrants, or that are rare, but less likely to be recognized by practitioners have been selected for a more detailed discussion. Other diseases, including some found in other chapters, have been included in table form according to their clinical appearance (Table 25.2).

Table 25.2 Tropical dermatology quick reference: differential diagnosis

Papular Lesions

Scabies

Although scabies has been a scourge of humans for thousands of years, it has enjoyed a resurgence recently because of the HIV epidemic and its association with a form of disease which is highly infectious due to the large numbers of mites present. Scabies is caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabei var. hominis, an ectoparasite requiring an appropriate host on which to feed. Symptoms of scabies usually begin 10–30 days after the onset of the infection, but may occur within 48 hours of a repeat infection because of host hypersensitivity.6,7

Human scabies is transmitted mainly by direct personal or sexual contact, and less often by contact with infested bedding or clothing. The gravid female mite burrows into the skin. Mature adults lay eggs at the rate of two or three per day, and a new cycle of replication will occur. At any given time, the average infected human has approximately 10–15 adult female mites. Scabies is characterized by severe pruritus. The characteristic primary lesion is the burrow. It appears as a white or gray linear, raised papule with a small vesicle at one end. These primary lesions are found in the web spaces of the fingers, on the flexor surfaces of the wrists and the elbows, on the penis, the scrotum, umbilicus, beltline and on the areola of the breasts in women. Secondary papules, pustules, vesicles, and excoriations may be present. The secondary lesions, often more numerous and more spread out than the burrows, likely represent an immune response to the infection. While scabies lesions are very uncommon on the head and neck area, infants not infrequently have involvement of the face and may have widespread, extensive lesions.

Norwegian or crusted scabies occurs in those patients who are immunocompromised, particularly among homeless individuals and those with AIDS. In this infection, the individual has severe cutaneous crusting due to hundreds to thousands of adult mites.8 In contrast to scabies in the immunocompetent host, papules and burrows may be limited or absent and pruritus may not occur. Crusted lesions may be found in the head and neck region and are found around the buttocks and perianal region.

Treatment of scabies includes management of the pruritus, treatment of secondary bacterial infection, eradication of the scabies mite, and prevention of secondary transmission.9 Topical antiscabetic treatments include sulfur compounds, benzyl benzoate, crotamiton oil, lindane, malathion, permethrin, and ivermectin. Currently, the drugs of choice include 5% permethrin and ivermectin. The former should be applied from the neck down at bedtime and washed off in the morning and repeated in 1 week. All household members should be treated and all bedding and clothing of the symptomatic case should be washed in hot water. Ivermectin, in a single dose of 150–200 μg per kg, is a very safe avermectin derivative that is taken orally.10,11 It is the treatment of choice for Norwegian scabies and in the case of an institutional outbreak. It is a convenient oral medication, but may be costly when a large family requires treatment. The pruritus of scabies may take 6–8 weeks to resolve after successful treatment because of the hypersensitivity reaction to parasite antigen in the skin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree