Sexuality, Sexual Function, and the Aging Woman: Introduction

Until recently, little has been known about women’s sexuality in later life. Negative societal attitudes about aging, sexuality among older people, and women’s sexuality in particular, present a significant barrier to scientific inquiry and medical attention to older women’s health concerns. Proven interventions for promoting female sexual well-being or treating women’s sexual problems are not widely available. Public health attention to older women’s sexuality is virtually nonexistent.

The 2005–2006 National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP), funded by the National Institutes of Health, provides the first population-representative, baseline data on sexuality among older women and men in the United States and informs many of the insights presented in this chapter. The study enrolled a national probability sample of 3005 community-residing men and women aged 57 to 85 years (75.5% weighted response rate), with oversampling of African-American, Hispanic, and men in the 75- to 85-year-old age group. About half the respondents were male, half were female, and they were divided approximately equally across three age strata: 57 to 64, 65 to 74, and 75 to 85 years. Respondents participated in a face-to-face questionnaire covering social, psychological, and health domains, including detailed information on sexual relationships and functioning. It is the first comprehensive, population-based study of older women’s sexuality.

This chapter first locates older women’s sexuality in a sociodemographic context, describes sexual activity, behaviors and problems experienced by women in later life, reviews physiological changes that affect sexual functioning as women age, and recommends a clinical approach to evaluation, prevention, and treatment of sexual problems common among older women. Older women, and their sexual relationships, are very heterogeneous. Generalizations made in this chapter, based on population data from the NSHAP study and findings from other sources, are rooted in statistical norms but should not be interpreted as a normative prescription for older women’s sexuality.

The interactive biopsychosocial model (IBM) provides a conceptual framework for understanding the relationship between sexuality and health throughout the life course (Figure 47-1). To the degree that medicine attends to matters of sexuality, the orientation is largely negative. The medical model approach to understanding sexuality focuses on sexual dysfunction as a problematic consequence of aging, disease, or treatment. Occasionally, medical texts suggest that older patients’ complaints about sexual problems, particularly male erectile difficulties, may herald serious underlying disease and ought not be ignored. While clinically valid, this narrow conceptualization of sexuality defies its multidimensional nature and limits understanding of the meaning of sexuality for health.

A broader framework, as defined by the IBM, conceptualizes a bidirectional relationship between sexuality and health. Sexual behavior can result in health problems, such as sexually transmitted infection, victimization, and, in younger women, unwanted pregnancy. Aging, physical and mental health problems, surgeries, and medications can cause sexual dysfunction. The IBM acknowledges this reciprocal relationship between sexuality and health but incorporates the possibilities that sexuality may also be health-promoting and that aging, or even illness, may confer advantages for sexual life.

In this model, health comprises biological, psychological, and social components and is conceptualized as jointly produced by a woman in conjunction with her spouse or other intimate partner. Joint production of health means that both partners of the couple contribute assets (or liabilities) to the “health endowment,” and these assets and liabilities impact the health of the other. The hourglass shape symbolizes the dynamic nature of both health and intimate relationships over time. Clinically, this model can be used as a mnemonic for the broad domains of inquiry pertinent to assessing a patient’s sexual history and reminds the clinician of the importance of ascertaining the presence, and health, of the patient’s intimate partner.

Sociodemographic Context of Older Women’s Sexuality

Sexuality in later life for most, but not all, people occurs in the context of a long-term marital relationship. For men, aging is largely a partnered experience. Men are significantly more likely than women to have a spouse or other romantic partner in later life and to be engaging in a satisfying sexual relationship, even despite a high prevalence of erectile difficulties. As a result of greater longevity, women, in contrast, are much more likely to experience aging, illness, and death without their life partner (Figure 47-2).

Figure 47-2.

Prevalence of relationships and sexual activity by age and health status. Panel A shows the percentage of survey respondents who were in a spousal or other intimate relationship. Panel B shows the percentage of respondents who were sexually active in the previous year among those with a spousal or other intimate relationship. Blue symbols denote men, red symbols women, plus signs respondents who reported being in excellent or very good health, triangles respondents who reported being in good health, and circles respondents who reported being in fair or poor health. (Adapted from Lindau ST, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762–774.)

Still, many older women regard sexuality as important for health and relationships and, among those with a spousal or other intimate relationship, many engage in regular sexual activity. Women tend to be less satisfied with sex in later life than their male counterparts and also report a high frequency of sexual problems including low desire, vaginal dryness, and difficulty experiencing orgasm. An older married woman is often healthier and more vital than her spouse and commonly assumes a caregiver role, which can interfere with the romantic dynamic of the relationship. Physical health problems, medications, and medical treatments affect the sexual lives of older couples; older heterosexual adults with a spouse or other intimate partner who are not sexually active most commonly attribute this to the male partner’s health problems.

Sexuality is widely valued by older adults, even those without a partner, as an important aspect of health and life. In his 2001 report, the U.S. Surgeon General, David Satcher, acknowledged that “Sexuality is an integral part of human life…Sexual health is inextricably bound to physical and mental health…(it) is not limited to the absence of disease or dysfunction, nor is its importance confined to just the reproductive years…” Although some aspects of aging are regarded as detrimental to sexual life, older women also identify ways in which aging is beneficial for sexuality (Table 47-1).

Effects of aging on sexuality | Beneficial | Partners know each other better; decreased sexual inhibition; more time; fewer distractions; know own body |

Detrimental | Less intense physical sexual response; increased inhibition because of poor body image; societal prejudice; need for secrecy | |

Effects of sexuality on aging | Beneficial | Better circulation; form of exercise; feeling of youthfulness or completeness; security of not being alone; pride in body; optimistic outlook on life; indicative of good general health; happiness/endorphins; physical release; physical outlet; alleviates arthritic pain |

Detrimental | Worry about transmitting or contracting infection; lost status as respected elder if sexually active |

Lack of formal sexuality education combined with widely restrictive social, religious, and cultural practices around female sexuality during much of the twentieth century have influenced the current generation of older women’s sexual expectations throughout their life. As a result, many report that they have never discussed nor would they initiate discussion of sexual matters with anyone, including their spouse. Most older women report that they have never spoken of sexual matters with a physician, yet feel that sexuality is an appropriate issue for physicians to address and that the physician, rather than the patient, should initiate the discussion (Table 47-2). Gender and age differences between women and their physicians can also present barriers to communication about sexual matters. In addition, older women perceive physicians to be poorly trained to deal with patients’ sexual concerns and that physicians presume older women to be asexual or disinterested (Table 47-2).

Why patients don’t discuss sex |

|

Why physicians don’t discuss sex |

|

Aging of the baby boomers, the generation of the sexual revolution, is expected to increase demand for medical attention to sexual matters over the next several decades. Although male longevity is expected to increase, older women will continue to outnumber older men through 2050; this presents a significant gender disparity in the opportunity for formation of new sexual relationships in later life and, in some cases, results in multiple women sharing a single male partner. Little is known about the implications and consequences of nonmonogamy in later life, but health assessment of older women, as discussed in detail below, should include questions to ascertain sexual activity, number of current sexual partners, and partner monogamy as this information may be relevant to risk for sexually transmitted disease (STD) and/or psychological well-being.

Although older women’s sexuality has largely been a taboo subject, residential institutions for elderly people have long recognized that sexual expression and desire continue even among individuals affected by dementia, frailty, and other life-threatening illness. Dementia, mental illness, and some medications, including dopaminergic medications such as those used to treat Parkinson’s disease, can result in sexual disinhibition or hypersexuality, sometimes directed at nursing home staff. The U.S. federal and many state governments declare a right to privacy for residents of nursing homes or elder care institutions; protection of privacy for sexual expression by institutionalized elders is not explicitly guaranteed by the government and therefore relies on individual institutions and providers to respect privacy and maintain individuals’ sexual dignity.

Some responsive institutions have addressed this problem by providing private rooms for residents and by training staff to understand and accept elder sexuality in a respectful manner. Sometimes, sexual relationships form among older residents with dementia who have, but may not remember, a community-residing spouse. Likewise, community-residing spouses may initiate new intimate relationships while maintaining involvement with and commitment to their institutionalized spouse. The implications of these relationships for health and integrity in later life are a growing reality, but poorly understood and often a cause of distress for families. Sexual exploitation and abuse of older women living in residential facilities (and in the community) is poorly documented, but vulnerability is heightened by cognitive impairment, which can interfere with a woman’s ability to consent to sexual relations.

Sexual Activity, Behavior, and Problems

The NSHAP study provides the first comprehensive population-representative data on sexual activity, behavior, and problems experienced by community-residing women (and men) aged 57 to 85 years in the United States. For older women, sexual activity is largely determined by availability of a sexual partner. Among women aged 57 to 64 years, about 85% have a current spouse or other romantic or intimate partner. Nearly all of these relationships are reported as heterosexual, monogamous, and involve sexual activity. However, the proportion of women with a partner declines with age, because of earlier male mortality, and by age 85 years, only about 40% of women have a partner, and fewer than 20% engage in sexual relations.

As compared with younger women, those 57 years and older report fewer total sexual partners over the lifetime. In the NSHAP study, 5% of women reported ever having a female sexual partner and only 5 women (0.3%) reported currently being in a relationship with another woman. Although data on lesbian relationships at older ages are very limited, estimates from the younger population suggest that women in this study may have underreported same-sex relationships. Additionally, qualitative research and clinical experience reveals cases of older women choosing or demonstrating receptivity to female partners for the first time in later life. Some women explain this as a choice caused by the scarcity of men and others are fulfilling a lifelong interest. Most sexually active older women report that their relationships are monogamous. However, women with nonmarriage partners are significantly more likely to report that their partner has had other sexual partners during the relationship. In the NSHAP study, nearly 1 in 10 married women and twice as many nonmarried women with a sexual partner believed that their current partner had other sexual partners during the relationship.

Among those who are sexually active (defined in the NSHAP study as engaging in “any mutually voluntary activity with another person that involves sexual contact, whether or not intercourse or orgasm occurs” during the prior 12 months), the kinds and frequency of sexual activity in which women engage are not substantially different from that observed among younger women. Most commonly, sexual activity involves vaginal intercourse, hugging, kissing, or other forms of sexual touching, and about 45% of sexually active women engage in oral sex. On average, the frequency of sexual activity for those with a sexual partner ranges between monthly and two to three times per month. Again, this is similar to that observed among younger sexually active adults. About a quarter of women aged 57 to 85 years report masturbating in the previous year. Interestingly, the prevalence of masturbation among women without a partner is the same as it is among women with a partner. This is also true for older men (50% report masturbating) and suggests that older adults maintain an individual desire for sexual pleasure and/or release, even in the absence of a sexual partner.

Among sexually active women, approximately half report having one bothersome sexual problem; almost one-third report having two. In contrast to older men whose sexual problems are heavily concentrated around erectile difficulties, older women are more likely to have sexual problems in multiple domains. The most common sexual problems experienced by older women are summarized in Table 47-3. Lack of interest in sex, pain with intercourse, unpleasurable sex, and inability to experience orgasm are much more common among older women as compared with their male counterpart. Of course, some proportion of sexually inactive women discontinued sexual activity as a result of bothersome sexual problems and, therefore, the NSHAP study underestimates the prevalence of problems in the whole population. On the other hand, many older women engage in sex despite bothersome problems. The explanation for this is unknown: the rewards or gains of sexual engagement may outweigh these negative experiences, some women may obligatorily participate in sex, others may lack the ability to refuse.

PERCENTAGE BY AGE GROUP† | |||

|---|---|---|---|

57–64 | 65–74 | 75–85 | |

Lacked interest in sex (n = 504) | 44 | 38 | 49 |

Difficulty lubricating (n = 495) | 36 | 43 | 44 |

Unable to climax (n = 479) | 34 | 33 | 38 |

Pain during intercourse (n = 506) | 18 | 19 | 12 |

Sex not pleasurable (n = 498) | 24 | 22 | 25 |

Anxious about performance (n = 500) | 10 | 12 | 10 |

Avoided sex because of problems (n = 357) | 34 | 30 | 23 |

Problems related to sexuality in later life, including female sexual dysfunction, can result from sexually transmitted infection, trauma, and sexual violence or abuse. These topics are discussed below. Sexual dysfunction, including clinical diagnosis and treatment, is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and NSHAP provide the only U.S. population prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among older women. Overall, prevalence of most infections in the general population is very low, although it maybe higher in some elder residential communities or geographic regions with high concentrations of sexually active older adults (e.g., Florida and Hawaii in the United States), or in other subpopulations. STD prevalence among older adults is likely underestimated because of lack of uniform tracking systems and underidentification in the clinical setting. One study showed that physicians are more likely to counsel older African-American and married women about human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other STDs, but the majority of older women report that a physician has never initiated such discussion.

Viral infections, including genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) and human papillomavirus (HPV), are among the more prevalent STDs found in older women. HSV-2 seroprevalence among men and women 70 years and older based on NHANES III data (1988–94) was 28%, but women had a higher overall prevalence than men and rates were much higher among blacks (74%) and Mexican Americans (45%). High-risk, or oncogenic, HPV (HR-HPV) prevalence among women aged 57 to 85 years, based on 2005–2006 NSHAP data was 6% and did not vary significantly across age or racial/ethnic groups. The prevalence of this sexually transmitted infection is similar to that documented by NHANES for women aged 50 to 59 years and calls into question age-based eligibility criteria for screening and prevention strategies, including implementation of HPV vaccination.

While there is evidence for new infection in later life as a result of sexual transmission, and infection of sexual partners by infected older women occurs, the majority of incident infections occur earlier in life and either persist or are latently expressed. HR-HPV is an important factor in cervical dysplasia and cancer, a leading cause of female cancer death in the world. In the United States, about 20% of cervical cancer cases, but more than a third of cervical cancer deaths, occur in women aged 65 years and older. Most screening and prevention strategies, including HPV vaccine, use age-based eligibility criteria that largely exclude older women.

Although data are very limited and likely underestimate prevalence (as explained above), population incidence estimates of other STDs among older women are lower than 1% for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, and Syphilis. U.S. population data on Trichomonas vaginalis among older women are not available; late twentieth century data from Danish and Chinese epidemiological studies indicate that very few cases occur among women older than 60 years. Changes in the cervical epithelium caused by loss of estrogen in older women may account for reduced susceptibility to some infections such as HPV and Chlamydia.

The vast majority of cases of HIV/AIDS in the United States and the world occur among people younger than age 50 years. However, the rate of new HIV infection among older women in the United States, particularly those of minority racial and ethnic groups, has been increasing over the last several years, due mostly to transmission by heterosexual sex. Prolonged survival of individuals infected with HIV in their fourth and fifth decades primarily accounts for increasing prevalence of HIV and AIDS in the United States among older adults. Of all prevalent HIV infections in the United States, 10% to 13% are estimated to occur among people aged 50 years and older. In 2002, 25% of Americans diagnosed with HIV/AIDS after the age of 55 years were women. Public health messages regarding HIV/AIDS prevention and detection have not targeted older women, and physicians rarely offer HIV counseling or testing to this group.

STD prevention strategies have not been well-tested for older adults. Few older women, including those in nonmarital sexual relationships, report using condoms. Condom use by older couples to prevent STDs may be compromised by similar knowledge, communication, behavioral, and cultural barriers experienced by younger couples and by changes in male and female physiology that occur with age. A condom is best applied when the penis is fully erect, but for some older men, full erection may not occur until after coitus is initiated. For women, increased susceptibility to condom-induced vaginal irritation or abrasion may result from vaginal dryness and/or atrophy caused by estrogen depletion.

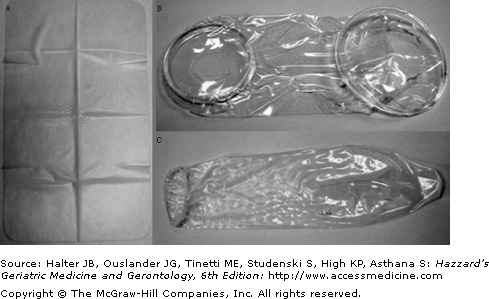

Counseling women with new or multiple sexual partners warrants attention to prevention of STDs including discussion of barrier methods such as male and female condom and the dental dam (for oral sex) (Figure 47-3). Couples receptive to using condoms should be taught proper application, encouraged to use foreplay to encourage full penile erection and maximal female arousal before penetration, and consider water-based lubricants (oil-based lubricants or vaginal medications can reduce condom effectiveness) to reduce vaginal and vulvar friction. Condoms with spermicide are not necessary for postreproductive age women and should be avoided because they have a shorter shelf-life and have been associated with urinary tract infection in younger women. Male and female condoms and dental dams are for one-time use only.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree