Learning objectives

- •

The importance of screening for osteoporosis.

- •

Risk factors predisposing to osteoporosis.

- •

Who, when, and how to screen for osteoporosis.

- •

Unnecessary laboratory and imaging studies should be avoided.

The case study

Reason for seeking medical help

- •

SF, a 51-year-old Caucasian woman, is concerned about osteoporosis because the mother of her best friend died about 4 weeks ago after sustaining a fragility hip fracture subsequent to a fall in her carpeted bedroom. SF is asymptomatic and enjoys good health. She is asking whether she should have a DXA scan done.

Past medical and surgical history

- •

No height loss.

- •

No history of falls, near-falls, dizzy spells, and no fractures.

- •

No history of arthritis, no renal calculi, no food allergies, regular bowel functions.

- •

Menarche at age 12 years, regular menses up to about a year ago.

- •

Five healthy children aged 25, 23, 21, 19, and 15 years. She breast-fed all, each one for approximately 1 year.

Lifestyle

- •

She drinks on average one glass (8 oz) of milk and a glass of calcium-fortified orange juice every day. She also has a cup of yogurt (6 oz) daily and regularly eats cheese (at least two slices) and calcium-fortified bread (at least two slices).

- •

She drinks only one cup of coffee every morning.

- •

She avo

- •

ids salty food.

- •

She does not consume soda drinks.

- •

She never smoked cigarettes.

- •

She drinks a glass of wine four to five times a week with dinner. She does not exceed one small glass.

- •

She leads an active physical lifestyle. She was in the army for about 25 years and then became a physical education teacher and personal coach. She spends at least an hour, five times a week in a gym doing a combination of aerobic and resistive exercises.

Medication(s)

- •

Multivitamin tablet once a day.

Family history

- •

Negative for osteoporosis; both parents are alive, healthy, and lead physically active lifestyles.

- •

Two older sisters (56 and 54 years) and two younger ones (49 and 47 years) all in good health, on no medication.

Clinical examination

- •

Weight 107 pounds, height 5′5″, arm span 65″, BMI 18.4. Except during her five pregnancies, SF’s weight has always been around 110 pounds. She had been investigated for low body weight about 10 years and again 2 years ago and no pathology was identified. Hyperthyroidism, celiac disease, malabsorption, anorexia nervosa, and the female athlete syndrome have been ruled out.

- •

No significant clinical finding: no kyphosis, no loss of height, no point tenderness along the vertebral spines, no localized paravertebral muscle spasms, no limitation in the range of movement of the lumbar vertebrae.

Laboratory result(s)

- •

A complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), serum thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and 25-hydroxy-vitamin D levels done about 6 weeks ago, as part of her annual medical checkup, were within normal limits.

Multiple choice questions

- 1.

In SF’s case, the following increase the risk of osteoporosis:

- A.

Female gender.

- B.

Caucasian race.

- C.

Alcohol consumption.

- D.

A and B.

- E.

A, B, and C.

Correct answer: E

Comments:

Osteoporosis is the most common metabolic bone disease. It affects both genders and all races, but women more frequently than men, and Caucasians more than Blacks. Fragility fractures are expected to affect about 50% of the female population over the age of 50 years and 25%–30% of the male population.

Osteoporosis is silent, i.e., asymptomatic, until a fracture is sustained. However, once a fragility fracture is sustained, the risk of further fractures is substantially increased, and the long-term outcome often is not good, even after the patient receives excellent orthopedic care. Many patients also enter a downward spiral: pain, limited physical capability, fear of falling, reduced exercise tolerance, withdrawal, unsteadiness, reduced cognitive functions, further gradual withdrawal from physical activities, worsening muscle wasting, sarcopenia, unsteadiness, cognitive impairment, and increased risk of falls and fractures. Once this cycle is entered it is difficult to overcome and reverse.

An osteoporosis treatment gap has been identified and needs to be addressed: men are less frequently screened for osteoporosis and, compared to women, are less frequently diagnosed and treated. Underdiagnosis is a major factor in the development of this treatment gap.

It is easier, more effective, and cheaper to prevent a fracture than to manage it, rehabilitate the patient, and prevent another fracture from occurring. And yet, many patients with fragility fractures, i.e., the hallmark of osteoporosis, are neither identified nor treated for the osteoporosis.

Screening is the first step toward identifying patients with, or at risk, of having osteoporosis. To this effect a number of assessment tools have been developed including the Simple Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE), Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI), Osteoporosis Index of Risk (OSIRIS), DXA-HIP Project, and Osteoporosis Self-Assessment tool.

It is sobering to realize that in women over the age of 50 years, the projected incidence of osteoporotic fractures exceeds the combined risk of myocardial infarction, strokes, and breast cancer, and yet, osteoporosis remains largely underdiagnosed and undertreated, even after a fragility fracture has occurred. A fragility fracture is defined as a fracture precipitated by trauma that ordinarily would not be expected to result in a fracture. Sometimes the osteoporotic fracture occurs spontaneously in the absence of trauma or while managing her daily activities and is referred to as “atraumatic fracture.”

Women are more susceptible than men to develop osteoporosis, and White women are more at risk of sustaining fractures than African American women. This may be due to several factors including a smaller bone mass, hip axis length, and femoral neck geometry. Several other nonmodifiable risk factors affect the risk of fractures, including age, parental history of hip fracture, age of menarche, and menopause.

Seventy to 80% of peak bone mass is genetically determined, and several genes have been associated with osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. Twenty to 30% of peak bone mass is determined by nongenetic, potentially reversible factors such as poor nutrition, cigarette smoking, sedentary lifestyles, and lack of physical exercise. Several other risk factors such as older age; parenteral history of fracture, especially hip fractures; age of menarche; and menopause are nonmodifiable. Pregnancy- and lactation-associated osteoporosis has been described. They are nevertheless rare.

Alcohol consumption in moderation, i.e., one to two daily serving, is associated with an increased bone density and possibly a reduced fracture risk. A cellular mechanism has been advocated for the apparent positive effect of moderate alcohol intake. It is, however, not clear whether these apparent positive effects of moderate alcohol consumption are due to the alcohol intake, per se, or whether they reflect the lifestyle of people who consume alcohol only in moderation, such as leading a more active physical lifestyle and having a better nutritional intake than those who abuse alcohol. Notwithstanding, it is not recommended to encourage nondrinkers to start consuming alcohol to improve their bone health.

In the USA, a standard alcoholic drink is:

12 oz of beer

5 oz of wine

1.5 ounce of spirits

Excessive alcohol consumption, on the other hand, is associated with reduced bone mineral density and increased risk of fractures. In addition, excessive alcohol intake interferes with balance, equilibrium, and postural reflexes, thus inducing unsteadiness and increasing the risk of falls and subsequent fractures. Excessive alcohol consumption also has negative effects on gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and hepatic functions which may interfere with the gastrointestinal absorption of calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D metabolism. Excessive alcohol consumption is also often associated with undernutrition and malnutrition. SF consumes alcohol only in moderation, and there is no need to recommend she changes her habits ( Table 1 ).

Table 1

Recommended daily calcium and vitamin D intake.

Adapted from Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference In takes for Vitamin D and Calcium. Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, et al. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2011.

Calcium

Vitamin D

Age group

RDA a

ULI b

RDA a

ULI b

Years

mg/day

mg/day

IU/day

IU/day

1–3

700

2500

600

2500

4–8

1000

2500

600

3000

9–18

1300

3000

600

4000

19–50

1000

2500

600

4000

51–70, men

1000

2000

600

4000

51–70, women

1200

2000

600

4000

>70

1200

2000

800

4000

a RDA: recommended daily allowance.

- A.

- 2.

SF’s low body could be due to:

- A.

The female athlete syndrome.

- B.

Anorexia nervosa.

- C.

Malabsorption.

- D.

Would be significant if she weighed less than she did when she was about 25 years old.

- E.

B and C.

Correct answer: D

Comments:

As body height, body weight, and body fat are closely intertwined, the Body Mass Index (BMI) is a measure derived from body height and weight and is used in the evaluation of patients with low or elevated body weights. The NIH classifies BMI as follows: underweight: ≤18.5, normal weight: 18.5–24.9, overweight: 25–29.9, and obese ≥30. SF’s BMI is 18.4, marginally below normal. Although all listed conditions are associated with low body weight, it is unlikely that SF has any of these conditions. As she has been menstruating regularly, it is unlikely she has either the female athlete syndrome or anorexia nervosa. Malabsorption is a possibility. However, in the absence of any other supporting evidence, and given her regular bowel functions, and that she has been previously thoroughly investigated twice for low body weight, malabsorption remains a possibility rather than a probability. The normal serum TSH level rules out hyperthyroidism.

A body weight less than 127 pounds, per se, increases the risk of osteoporosis. Similarly, postmenopausal women who weigh less than they did when they were 25 years old have an increased fracture risk ( Fig. 1 ).

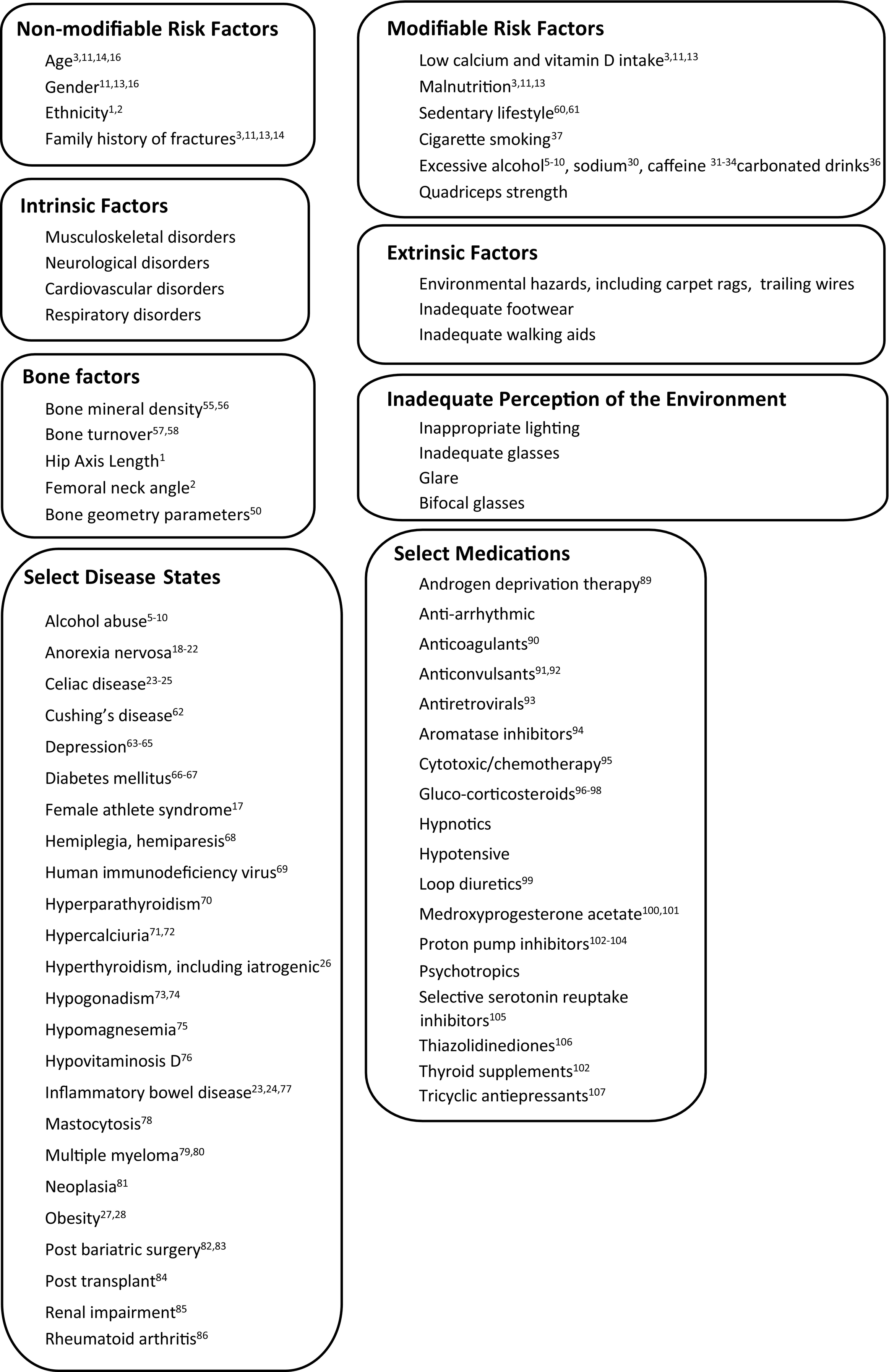

Fig. 1

Factors increasing fracture risk.

Although obese patients are less likely to develop osteoporosis because of the additional weight, obesity may increase the risk of osteoporosis possibly because the increased adipose tissue may be associated with hypovitaminosis D and secondary hyperparathyroidism. SF weighs 107 pounds, she is 64″ tall, her BMI is 18.4, just below the normal range.

- A.

- 3.

Excessive intake of the following increases the risk of bone demineralization and osteoporosis:

- A.

Sodium.

- B.

Caffeine.

- C.

Phosphoric acid.

- D.

A and B

- E.

A, B, and C.

Correct answer: E

Comments:

All listed food ingredients may induce a negative calcium balance and increase the risk of bone demineralization. Excessive sodium and caffeine intake increases the renal calcium excretion. Phosphoric acid, often found in soda and carbonated drinks, binds to calcium in the gastrointestinal track and interferes with the calcium bioavailability. A positive association between caffeine consumption, urinary calcium excretion, and fractures has been documented ( Table 2 ).

Table 2

Approximate calcium content of select food. a

Calcium content of food, data obtained by surveying labels in food stores

Milk, 8 oz b

300 mg

Milk fortified with calcium, 8 oz

500 mg

Soya milk, 8 oz

500 mg

Chocolate drink with water, 8 oz

300 mg

Chocolate drink with milk, 8 oz

600 mg

Chocolate drink with calcium-fortified milk, 8 oz

800 mg

Orange juice fortified with calcium, 8 oz

300 mg

Yogurt, 6 oz

400 mg

Cheese, 1 slice

100 mg

Cheese, 1 cube, 1″ side

200 mg

Bread, one slice, fortified with calcium

100 mg

Anchovies, 3 oz

125 mg

Sardines, 3 oz

320 mg

Select green vegetables

100 mg

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

- A.