CHAPTER 48 Screening for Mental Health Problems and History of Torture

Screening for Mental Health Problems

Primary care clinicians may encounter refugees in a variety of settings delivering primary healthcare services, including community- and hospital-based ambulatory care clinics, public health screening programs, school-based programs, and resettlement agency programs. Evidence for screening – defined here as the early identification of patients with unsuspected and remediable mental health disorders – in any of these service settings is slowly developing. From an evidence-based medicine and public health perspective, screening must be shown to fulfill several criteria. These criteria include: (1) that the screening detects important and treatable disorders; (2) that screening instruments exist that are effective, practical, and acceptable to both patient and provider; and (3) that the screening is effective in routine practice settings, not only in research settings. As discussed elsewhere in this book, the mental health disorders that clinicians might screen for, such as major depression, are prevalent and treatable. However, fulfilling the second and third criteria remains problematic and forms the subject of this chapter.

Mental Health Instruments

Primary care providers working with immigrants and refugees may select from a wide variety of instruments to assess for mental health problems (Table 48.1).1–4

Table 48.1 Selected instruments for assessing refugee mental health in primary care settings1–3

| Measurement subject | Languages translated | Validity/reliability testing in any refugee groups |

|---|---|---|

| PTSD | ||

| Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) | Bosnian, Cambodian, English, Dari, Khmer, Laotian, Vietnamese | Yes |

| Impact of Events Scale (IES) | Spanish, Serbo-Croatian, English | Validity, yes; reliability, no |

| Post-traumatic Stress Checklist-Civilian | Spanish, English | Yes |

| Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) | English, Farsi, Pashto | Yes |

| DSM-IIIR PTSD Checklist | Cambodian, English, Laotian, Vietnamese | Validity, no; reliability, yes |

| Anxiety | ||

| Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25) | Amharic, Bosnian, Cambodian, Dari, English, Khmer, Laotian, Pashto, Tibetan, Vietnamese | Yes |

| Health Opinion Survey | English, Khmer, Laotian, Persian, Spanish, Vietnamese | No |

| PRIME-MD | English, Spanish | No |

| Anxiety disorder module of the Structured | Spanish, Vietnamese, English | Yes |

| Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) | ||

| Depression | ||

| Hopkins Symptom Checklist, Depression (HSCL-25) | See Anxiety | |

| Zung Depression Scale | Cantonese, English, Hmong, Laotian | Validity, no; reliability, yes |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) | English, German, Russian | No |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | Dari, English, Hebrew, Pashto, Turkish, Russian | Yes |

| CES-D | Bosnian, Chinese, English, Hebrew, Pashto, Russian, Turkish, Korean, Portuguese, Spanish, Vietnamese | Validity, no; reliability, yes |

| PRIME-MD | See anxiety | |

| Vietnamese Depression Scale (VDS) | Vietnamese, English | Yes |

Unfortunately, no instrument has been studied in all the refugee populations that primary care providers will encounter. Choices among instruments include language availability, domains of interest (depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder), length, and evidence basis in the target population. For instance, if clinicians are caring for Spanish-language immigrants, modules of the PRIME-MD7 and the Post-traumatic Stress Checklist–Civilian8,9 may be useful. Other instruments commonly used in refugee populations include part 4 of the self-report Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ),10 the 25-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25),11 and the Impact of Events Scale (IES).12 The HTQ lists 30 symptom items, 16 coming from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition (DSM-III-R) criteria for PTSD. However, its sensitivity and specificity in community samples is 16% and 100%, respectively, and it is unknown in primary care populations.13 The HSCL-25, a self-administered questionnaire originally designed to measure symptom changes in anxiety and depression, has been validated in the general US population and has good reliability and validity in clinical refugee samples. An average-item score greater than 1.75 indicates clinically significant distress. The Impact of Events Scale has been used to screen for PTSD; it has 15 items on 3-point descriptive scales measuring intrusive thoughts and somatic sensations and avoidance behaviors after trauma.

Inquiring About a History of Torture

When a mental disorder such as depression or PTSD is diagnosed, primary care providers should inquire about traumatic exposures and human rights violations that may be associated with the disorder. Where such events, such as torture, are reported, it is important to document the events and the resulting mental health problems to support legal claims.14 This includes asking for details of trauma exposure as well as documenting physical, emotional, and mental health evidence of torture or abuse. Linkages with other health professionals, including professional organizations, local human rights organizations, and international partnerships can be important in addressing this forensic documentation.15 Organizations such as Physicians for Human Rights (http://www.phrusa.org/) and Doctors without Borders (http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/) can provide training, resource materials, and even services that assist primary care providers document the effects of torture and abuse. Documentation should only occur if agreed to by the patient.

While often there is an expectation that diagnostic processes may be complicated due to patients’ reluctance to speak about their traumatic experiences, in fact patients are usually accepting of physicians’ inquiries about violence exposure. Furthermore, research shows that, in the process of screening, refugees are often willing to let health professionals know they are suffering and accept help in the form of mental health intervention.16,17

Recommendations for torture detection instruments in research settings are that they utilize a ‘checklist’ approach that includes specific torture and trauma events to determine exposure to torture.18 This avoids the problem of differing conceptualizations of torture that may exist between cultures. Several traumatic event checklists are available, each developed for a different cultural group with different trauma events. To date, no screening instrument has been tested and validated for its ability to identify persons with a history of torture in primary care settings. Previous studies have used the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) to measure whether or not participants had experienced torture.10 The HTQ was designed to empirically measure trauma events and PTSD in Indochinese patients referred to a specialty mental heath clinic. It has one item inquiring about a history of torture, embedded within 17 items chosen to be historically accurate for this population’s trauma experience. Although the health components of the HTQ have been validated, the torture items have not yet been validated. The HTQ validation study sample, moreover, had a known high prior probability of exposure, and thus the effect of spectrum bias on particular items is uncertain.

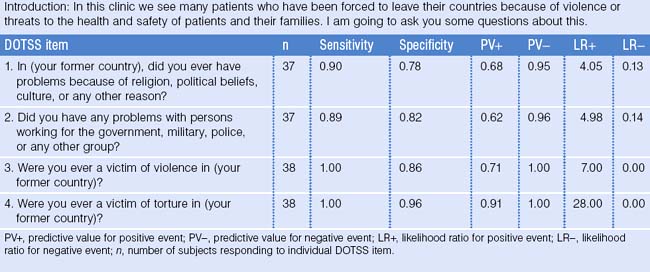

Since this study was not conducted in populations that are representative of general clinic populations, we designed and tested a single item inquiring about a history of exposure to torture. Our objective was to validate the use of one question regarding a first-hand experience of torture that is embedded in a context of rapport-building and context-setting questions. We developed the Detection of Torture Survivors Survey (DOTSS) to accurately identify individuals who have been exposed to torture in the heterogeneous populations that attend ambulatory care clinics.19

Data were collected from a convenience sample of foreign-born adult patients (born outside of the United States and US territories) who presented to the emergency department or adult primary care clinic. Patients with altered mental status, or located in the critical care section of the emergency department, were excluded. Interviews were performed in English or Spanish, and interpreters were provided for other languages when necessary.

Inter-rater reliability was determined by having both research assistants score responses to the assessment instruments at the same time. Convergent validity was examined using the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) to determine the presence or absence of a history of torture. This scale was selected as a comparative measure since it currently serves as a screening tool for measuring torture events and trauma. Participants also underwent a blinded in-depth clinical interview to determine criterion validity. The blinded interviewers were all drawn from the clinical staff of the Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture and are all trained physicians or psychologists with several years of diagnostic, therapeutic, and research experience with torture. A clinical reference was chosen for criterion validity because a prior study found a clinical interview to have good diagnostic accuracy for defining exposure to torture.20 The clinical assessment determined whether the participant had been tortured as defined by the World Medical Association, Declaration of Tokyo, which states that torture is: ‘… the deliberate, systematic or wanton infliction of physical or mental suffering by one or more persons acting alone or on the orders of any authority, to force another person to yield information, to make a confession or for any other reason.’21 Final clinical assessment of exposure to torture was made after discussion with the study investigators. In no cases did the clinical interview or study investigators disagree on exposure status.

The degree of agreement between the two raters on the DOTSS was determined with Kappa coefficients of inter-rater reliability. The mean Kappa coefficient for the 16 DOTSS items (including DOTSS sub-items) was 0.94 ± 0.09 (range = 0.78–1.00). Results of the blinded, in-depth clinical interview were compared to answers from the 9 DOTSS-base items to evaluate the success of the DOTSS as a screening instrument for a history of torture. ‘Were you ever a victim of torture?’ was highly predictive of torture/not tortured status on the basis of the blinded in-depth clinical interview (Table 48.2). In fact, this item correctly classified 37 out of 38 cases (LR+ = 28). The success of the DOTSS as a screening instrument for assessing exposure to torture is demonstrated by its convergent validity with the HTQ. The association between total scores on the DOTSS and HTQ was examined by calculating a Pearson correlation (r = 0.94, p < .0001, n = 39). This correlation indicates that high total scores on the DOTSS were associated with high total scores on the HTQ.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree