| Schistostomes Schistosoma mansoni Schistosoma japonicum Schistosoma mekongi Schistosoma intercalatum, Schistosoma guineensis Schistosoma haematobium | South America, Caribbean, Middle East, Africa China, Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand Cambodia, Laos West and Central Africa Africa, Middle East |

| Biliary and liver flukes Clonorchis sinensis Opisthorchis viverrini Opisthorchis felineus Fasciola hepatica | China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Vietnam Thailand, Laos, Cambodia Eastern Europe, former Soviet Union Europe, North Africa, Asia, western Pacific, Latin America |

| Lung flukes Paragonimus westermani and other species | Far East, South Asia, Philippines, Central and South America, West Africa, Mississippi River Basin (USA) |

| Intestinal flukes Fasciolopsis buski Heterophyes heterophyes Metagonimus yokogawai Nanophyetus salmincola | Far East Far East, Egypt, Middle East Far East Pacific Northwest |

Schistosomiasis

Clinical presentation

A history of contact with possibly infested freshwater in an endemic area should prompt an evaluation for schistosomiasis, even in the absence of symptoms (Figure 197.1). Clinical manifestations that suggest the diagnosis vary according to the stage of infection. Some persons complain of intense pruritus or rash shortly after the infective cercariae penetrate the skin. Previously uninfected visitors to endemic areas may develop acute schistosomiasis, or Katayama fever, 2 to 12 weeks after exposure, as the immune system responds to maturing worms and eggs. Symptoms range from mild malaise to a serum sickness-like syndrome that lasts for weeks and may be life-threatening. Common features include fever, headache, abdominal pain, myalgia, dry cough, diarrhea, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, urticaria, and marked eosinophilia.

Figure 197.1 Shallow pond infested with Biomphalaria, the snail host of Schistosoma mansoni in Brazil.

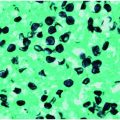

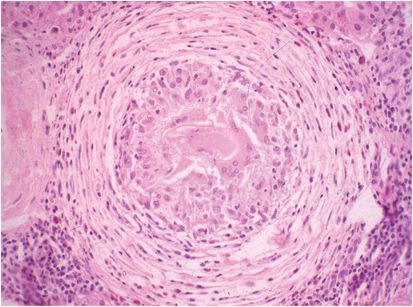

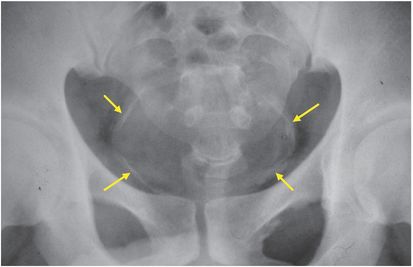

Chronic infections with schistosomes usually are asymptomatic; slight or moderate eosinophilia occurs frequently. Long-term residents of endemic areas may harbor heavy infections for long periods and thus are more likely than transient visitors to have symptoms. Disease results from egg deposition in tissues and the ensuing inflammatory and fibrotic response (Figure 197.2). In infections due to Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma japonicum, Schistosoma mekongi, Schistosoma intercalatum, and Schistosoma guineensis, involvement of the bowel leads to mucosal inflammation and microulcerations, diarrhea, bleeding, polyps, and strictures. Embolization of eggs to the liver results in hepatosplenomegaly, periportal fibrosis, portal hypertension, and esophageal varices. Hematuria and dysuria are early symptoms of chronic infection by Schistosoma haematobium; later, fibrosis and calcification of the bladder and lower ureters results in hydroureter and hydronephrosis (Figure 197.3), and squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder may develop. Ectopic deposition of eggs in the skin, genitalia, and other organs occurs during both the acute and chronic stages of infection. Transverse myelitis, seizures, and other serious sequelae result from egg deposition in the central nervous system. In endemic areas, chronic infections of even moderate intensity have been associated with anemia, poor nutritional status, and cognitive impairment.

Figure 197.2 Granuloma around egg of Schistosoma mansoni that embolized to the liver and was trapped in a small branch of the portal vein.

Figure 197.3 Plain radiograph of the pelvis showing calcification of the wall of the bladder and lower ureters (arrows).

Diagnosis

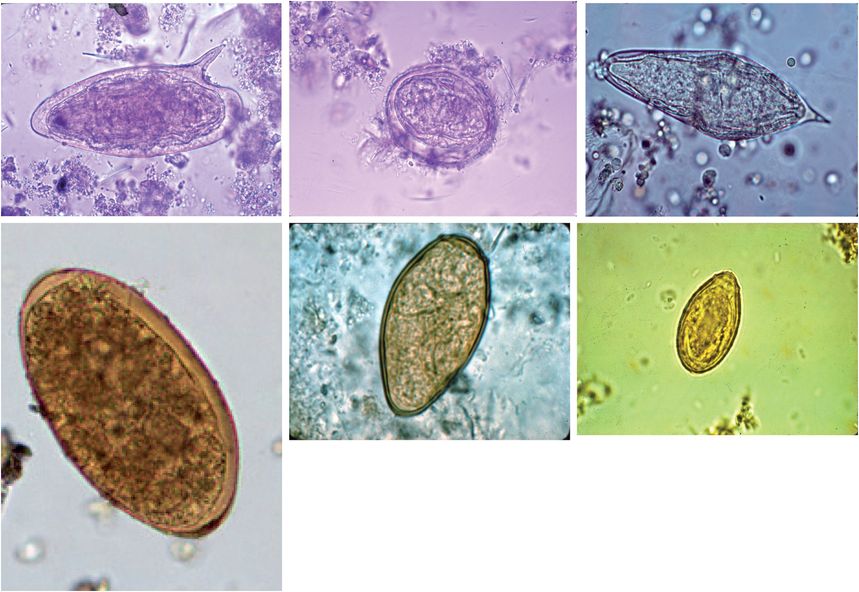

The most direct method of diagnosis is microscopic examination of stool or urine for schistosome eggs (Figure 197.4). Because egg output is low in light infections, concentration techniques and examination of several specimens obtained on different days should be routine. Eggs should be counted to estimate the intensity of infection and to monitor the response to therapy. Counts above 400 eggs per gram of feces or 10 mL of urine are considered heavy and are associated with higher rates of complications. Microscopic examination of snips of rectal mucosa obtained at proctoscopy may reveal eggs when stool examination is negative.

Figure 197.4 Trematode eggs. Top row, left to right: Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma japonicum, Schistosoma haematobium. Bottom row, left to right: Fasciola hepatica, Paragonimus westermani, Clonorchis sinensis.

Serologic tests for antibodies to schistosomes are available at commercial laboratories in the United States and at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta. The CDC uses a sensitive and specific Falcon assay screening test/enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (FAST-ELISA) for screening and a highly specific immunoblot for confirmation and species determination. These tests cannot distinguish active from past infections but are useful for the diagnosis of acute schistosomiasis before eggs are shed in the stool. Serologic tests should be used to screen previously unexposed travelers and expatriates; a positive serologic test is presumptive evidence of infection even if subsequent microscopy is negative.

Persons with confirmed infections due to the intestinal schistosomes should be evaluated with measurement of liver function tests and tests for chronic hepatitis B and C to rule out concomitant hepatocellular disease. Heavy infection or evidence of liver disease should prompt an ultrasound to document periportal fibrosis and signs of portal hypertension (Figure 197.5). Esophageal varices are visualized by barium swallow or endoscopy. Urinalysis, urine culture, and serum creatinine determination are indicated for persons with S. haematobium

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree