Rheumatoid Arthritis and Other Autoimmune Diseases: Introduction

Our understanding of the pathogenesis and approach to treatment of autoimmune diseases continue to evolve. However, key questions concerning the epidemiology, pathogenesis and optimal treatment of these diseases in the elderly population remain unanswered. Despite the many exciting new therapeutic advances, immunosuppression in elderly patients with autoimmune diseases continues to pose a dilemma. Changing population demographics and the advent of biologics, coupled with the lack of the availability of a rheumatologist in many smaller communities, will significantly impact the geriatrician’s role in the care of older adults with autoimmune diseases in the coming years. This chapter summarizes key recent advances, with specific references to the geriatric population.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that preferentially affects diarthrodial joints. The current and most widely used classification criteria for RA were developed in 1987 by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), based on the study of predominantly middle-aged patients attending hospital outpatient clinics (Table 120-1). While the criteria set is useful for diagnosing established and active disease in younger patients, its usefulness in detecting early disease and elderly-onset (>60 years old) rheumatoid arthritis (EORA) has not been established. This is important because the disease presentation in EORA may be distinct from that of young-onset RA (YORA).

Rheumatoid factor | Using a method with positive results in <5% of normal controls |

Rheumatoid nodules | Subcutaneous nodules over bony prominences, extensor surfaces, or in juxta-articular regions |

Radiographic changes | Typical changes of RA on hand and wrist radiographs, including erosions or unequivocal bony decalcification localized in or adjacent to the involved joints |

Arthritis of the hand joints | Swelling of wrist, metacarpal phalangeal (MCP), or proximal phalangeal (PIP) joints for at least 6 weeks |

Arthritis in three or more joints | Soft-tissue swelling or fluid present simultaneously for at least 6 weeks. Possible areas include PIP, MCP, wrist, elbow, knee, ankle, and metatarsal phalangeal joints |

Arthritis that is symmetrical | Simultaneous involvement of the same joint areas on both sides of the body for at least 6 weeks |

am (morning) stiffness | Morning stiffness in and around the joints, lasting at least 1 h before maximal improvement at anytime in the disease course |

One important advance that may lead to the eventual modification of the ACR classification criteria for RA is the discovery that the majority (70–90%, depending on the assay) of patients with RA has in their blood circulating anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies. Citrullination is a posttranslational modification of protein-bound arginine into the nonstandard amino acid citrulline, and many citrullinated proteins have been found to be expressed in inflamed joints. Anti-CCP antibodies are as sensitive as, and more specific than, IgM rheumatoid factor (RF) in early and fully established disease. Furthermore, the presence of these antibodies is a marker for erosive disease and may predict the eventual development of RA in patients presenting with undifferentiated arthritis. These antibodies may also be detected in healthy individuals years before the onset of clinical RA. Unlike classical RF, the incidence of anti-CCP antibodies does not appear to increase with normal aging, making it a particularly useful marker for this disease in the elderly population.

In addition to classification criteria for the diagnosis of RA, the ACR has established criteria for functional status and for determining clinical remission in RA. The usefulness of these classification systems in older patients who often suffer functional disability from concomitant osteoarthritis, soft-tissue rheumatism, and cardiovascular or neurological diseases is unclear.

Although the overall incidence of RA may be declining, the disease still affects approximately 1% of the population in the United States and in many western developed countries. Lower prevalence rates of 0.2% to 0.3% have been observed in China, Japan, some regions in Greece, and Africa. Southern Europeans may have a milder disease, with less extra-articular complications and less evidence of radiographic damage. Conversely, a much higher prevalence rate (up to 7%) and a more aggressive clinical course have been reported in several American-Indian and Alaska native populations. Gender and age are important factors in RA. Overall, women are affected by the disease two to three times more than men. However, this gender parity disappears in old age. The prevalence of RA increases with age and is commonest in the most elderly group studied (often 65 years and older or 70 years and older). Approximately 5% of women older than the age of 55 years are affected by the disease. The incidence of RA also increases with age, with the peak incidence occurring in the sixth to eighth decades (Figure 120-1). The reason for the age-associated increase in disease susceptibility is currently unknown.

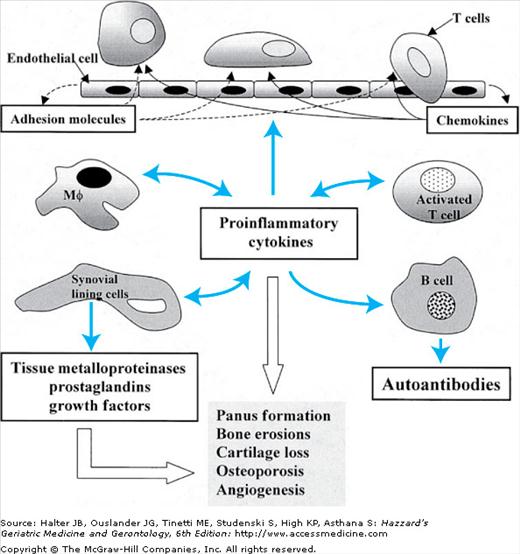

RA begins as a disease of the synovium. Earlier on in the disease the normally one- or two-cell-layer-thick synovium becomes markedly hyperplastic and edematous, accompanied by prominent new blood vessel proliferation. Left unchecked, this is followed by the activation and recruitment of T cells into the RA joint, which set into motion a complex cascade of inflammatory responses (Figure 120-2). This results in further accumulation of inflammatory cells, panus formation, localized osteoporosis, bony erosions, and destruction of periarticular structures, which are characteristic of this disease. Rheumatoid synovitis is accompanied by the accumulation of inflammatory joint fluid with white cell count typically in the range of 2000 to 20 000 cells per milliliter. Soluble proteins that have been implicated in the inflammatory process include a number of proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1, IL-6, IL-13, IL-15, and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]), metalloproteinases (stromelysin, collagenases, and gelatinases), transforming growth factor-β, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and activated complement components.

There appears to be a genetic susceptibility component to RA. The concordance rate for monozygotic twins is between 12% and 15%, approximately three times that of dizygotic pairs and much higher than the 1% background prevalence rate of the general population. The fact that most monozygotic twins are discordant for RA also highlights the importance of environmental factors. The association between RA and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) has been refined to alleles coding for a “shared” epitope (the sequences QRRAA or QKRAA) on the HLA-DRB1 genes. The presence of the DRB1*04 (DR4) allele (especially if both alleles are present) is a marker for increased susceptibility and severe disease. Population differences in the prevalence of the “shared epitope” may help to explain in part the geographic variation in the prevalence of RA.

An infectious etiology for RA has been postulated for more than half a century. The onset of RA can be heralded by polyarthralgias, fever, and malaise that are indistinguishable from an acute infection. The joints are known targets for diverse microorganisms from gonococci to Borrelia burgdorferi and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acute and chronic “reactive” arthritis can follow specific gastrointestinal (GI) or genital urinary infection. A transient RA-like illness can be seen in viral infections including parvovirus B19, Epstein–Barr virus, and human T-lymphotropic virus type 1.

Tantalizing evidence of a potential pathogenic role for microorganisms in RA includes the following: (1) Retroviral-like particles have been observed in RA synovial fluid. (2) Viral or bacterial superantigen can reawaken a latent or subclinical disease in animal models of inflammatory arthritis. (3) Heat shock proteins (viral and cellular) can act as autoantigens. Interestingly, both the dnaJ class of bacterial heat shock protein and the gp110 capsid protein of Epstein–Barr virus have the QKRAA “shared epitope” amino acid sequence.

Despite these observations, a direct role for infection in the pathogenesis in RA has not been proven. It is possible that transient exposure of the joints to microorganism protein with homology to normal antigen could attract lymphocytes to the synovium. This, in turn, may set up an autoimmune response through a molecular mimicry mechanism without requiring the presence of the inciting organism (the “hit and run” theory). Some investigators have shown that RA synovial cells may have defective apoptosis and a transformed phenotype. This opens up the possibility that environmental agents, including viruses, may transform synovial or lymphoid cells to cause inflammation and tissue destruction without requiring the presence of the inciting agent.

Gender differences in reproductive hormones may explain the high female prevalence in RA. However, since the peak incidence of RA in women is in their fifties, high levels of female sex hormones may play a modifying, but not necessary, role in the pathogenesis of this disease.

The linkage of RA to specific major histocompatibility complex alleles, the abundance of specific T-cell subsets in synovial tissue and fluid, and other evidence from animal models of inflammatory arthritis all point to a central role of T lymphocytes in the immunopathogenesis of this disease. RA is considered to be a Th (T helper) 1-mediated disease based on the cytokine and more recently the chemokine receptor profile of T cells in synovial joints. Although it is tempting to postulate that RA-associated DRB1 epitope triggers disease by presenting an arthrogenic peptide to T cells, extensive search of unique peptides that are displayed selectively by RA-associated HLA molecules has so far been unsuccessful. Costimulatory molecules, including CD28 and CD60, may play a role in activating T cells in RA joints. However, their precise role in human disease is unclear. Signal transduction through the T-cell receptor is defective in RA, suggesting that non-T-cell-receptor-activating pathways may be important in T-cell activation in this disease.

The reason for the age-associated increase in RA susceptibility is unclear. The traditional view that aging is associated with a “decline” in immune response does not explain the high incidence and severe onset of this autoimmune disease that is commonly seen in older adults. Decline in sex hormone production in postmenopausal years also cannot account for the high incidence of RA in elderly females. Unlike their younger counterparts, EORA occurs with equal frequency in males and females. Again, the rising incidence of RA in postmenopausal women suggests that while reproductive hormones may influence the disease manifestation, they are unlikely to play a major pathogenic role in the elderly population.

Animal studies suggest that aging is accompanied by a shift from a Th1 to a predominantly Th2 cytokine profile. However, such changes cannot explain the high incidence of RA, a predominantly Th1-mediated disease, in the elderly population either. Studies on the effect of age on the adenovirus vectors model of inflammatory arthritis have yielded conflicting results, with some strains showing more chronic and destructive arthritis in older female animals. The enhanced production of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-1, in aging, may contribute to the clinical features of EORA. The recruitment and retention of T cells in the RA synovial joint are complex processes determined by the interaction of leukocyte adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors interacting with their respective ligands expressed by synovial and vascular endothelial cells. T cells from aged animals may express high levels of selective chemokine receptors that are important in the recruitment of T cells to RA joints. These lines of research may eventually provide the explanation for the increased susceptibility and severity of RA in elderly people.

Whether EORA is a different disease from YORA is controversial. The clinical studies that address the issue were mostly descriptive or cross-sectional studies done in the 1950s and 1960s that have significant methodologic problems. The older definition of RA used in these studies also allowed terms such as “classical,” “definite,” and “probable” RA, which are no longer used today. As mentioned before, the most widely accepted classification of RA currently in use has not been validated in the elderly population.

Table 120-2 summarizes the features of EORA. In general, patients with EORA have a more equal gender distribution. The large joints, including the shoulder joint, are more often involved at presentation in EORA. Whether this is a result of concomitant rotator cuff disease that is prevalent in this age group is unclear. Symptoms in the proximal girdles have led to the belief that EORA may present with a polymyalgia rheumatica-like illness. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) normally increases with age, especially in females. Elevated ESR is also more common in EORA. The prevalence of RF similarly increases after the age of 60 years, reaching 30% by the age of 90 years. Earlier reports suggest a lower frequency of RF in EORA than YORA. However, this has not been confirmed in more recent studies. As in younger patients, patients with EORA who are seropositive for RF have more severe clinical disease, more bony erosions on x-ray, worse functional outcome, and increased mortality. Whether patients with EORA who are seropositive have worse prognosis than do their younger counterparts is unclear. It is possible that the poor prognosis of EORA reported in some studies reflects the greater number of comorbid conditions that are present in older patients.

Age of onset >60 yr |

Male:female ~1:1 |

Acute presentation |

Oligoarticular (two to six joints) disease |

Involvement of large and proximal joints |

Systemic complaints, e.g., weight loss |

Absence of rheumatoid nodules |

Sicca symptoms common |

Laboratory: high erythrocyte sedimentation rate; often negative rheumatoid factor |

“Benign polyarthritis of the elderly” person occurs in up to a third of patients with EORA. They have a more explosive disease onset associated with systemic features such as fever and night sweats. The clinical features have led some to describe the disease as “infectious like.” The disease is called benign because its general prognosis is good, with most people going into remission within 1 year with or without treatment. Within this group can be included a peculiar syndrome unique to the elderly population called the RS3PE (remitting, seronegative, and symmetric synovitis with pitting edema) syndrome. This typically affects elderly men (2–3:1, male:female ratio) and is characterized by acute onset of symmetric polyarthritis/tenosynovitis with pitting edema involving both upper and lower extremities. As the name implies, these patients generally have negative RF and antinuclear antibody (ANA). They often have high ESR and respond to low-dose prednisone. The association with HLA-B7 has been reported inconsistently. RS3PE may occasionally be associated with other rheumatic diseases, including polymyalgia rheumatica, spondyloarthropathies, psoriatic arthritis, RA, and sarcoid, and, rarely, malignancies.

The assessment of RA in older adults is different from that of the younger age group. The nonspecific symptoms and signs of RA are prevalent in the geriatric population. Rheumatic diseases that can mimic EORA, such as polymyalgia rheumatica, osteoarthritis, and crystal-induced arthritis, are prevalent in the elderly population. Anti-CCP antibody measurement may be useful in distinguishing EORA from polymyalgia rheumatica. In one small study, 65% of patients with EORA were anti-CCP antibody positive, but none of the patients with PMR or the aged healthy subjects had the antibodies. Arthritis associated with malignancy can be misdiagnosed as RA before the correct diagnosis is made months or years later. Other differential diagnoses of RA in the elderly population include inflammatory (erosive) osteoarthritis, late-onset spondyloarthropathy, endocrinopathy (e.g., hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, and diabetic cheiroarthropathy), amyloidosis, and the edematous phase of scleroderma. Conditions such as sarcoidosis, adult Still’s disease, hemochromatosis, and glycogen storage diseases can mimic RA but are unlikely to present for the first time so late in life.

In addition to the above considerations, the initial evaluation of an elderly patient with RA should include a careful assessment of the patient’s living condition, social support, and cognitive and functional status. Many elderly patients have the misconception that there is no effective treatment for arthritis, and they should accept their physical suffering as part of normal aging. Older adults are often embarrassed about their arthritis pain. They may minimize their symptoms by using terms such as “aching” and “stiff” instead of pain. Unfortunately, many clinicians also do not take their symptoms seriously, resulting in the patients frequently feeling that their care resembles “a lick and a promise.” Because pain is, by far, the commonest presenting symptom of RA, pain assessment should be an integral part of the patient’s evaluation at presentation and in subsequent office visits. This can be difficult in the elderly patient who has significant cognitive or verbal impairment. Information from caregivers, nonverbal pain behavior, physical evidence of active joint inflammation, and decline in functions are important clues that more aggressive therapy may be necessary.

The ACR classification system for assessing the functional status of patients with RA is shown in Table 120-3. However, use of this classification for an elderly patient may be difficult because of functional disability from other coexisting diseases. This quick assessment tool is useful for describing the global functional status and allows patients to be grouped for studies. Patients with RA with the worst (class IV) functional status were reported to have extremely poor prognosis, with survival similar to patients with multiple vessel coronary artery disease and stage IV Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Many clinicians now feel that the prognosis for RA has improved with the advent of better therapeutic regimens for RA in the past two decades. Whether this translates into prolonged survival remains to be determined. Concomitant medical conditions affecting the patient’s hearing, eyesight, continence, and balance need to be addressed to optimize functional ability and to prevent falls. Current and past medical histories are important elements of the initial evaluation. This information is important in determining the selection of specific treatment (see “Management” section). In contrast, family history is not as helpful in assessing elderly patients with RA.

Class I | Completely able to perform usual activities of daily living (self-care, vocational, and avocational) |

Class II | Able to perform usual self-care and vocational activities but limited in avocational activities |

Class III | Able to perform usual self-care activities but limited in vocational and avocational activities |

Class IV | Limited in ability to perform usual self-care, vocational, and avocational activities |

In addition to excluding diseases mentioned above, a new patient suspected of having RA should be tested for the presence of anemia, cytopenia, liver or renal dysfunction, RF, and elevated ESR. The presence of extremely high RF should prompt the clinician to consider the possible diagnosis of cryoglobulinemia. Some patients have negative RF but positive ANA. These patients tend to have more severe disease, similar to the patients with positive RF. A workup for secondary Sjögren’s syndrome should be done in patients with concurrent sicca symptoms (dry eye and dry mouth). In general, ESR is a better indicator of disease activity than changes in the titer of RF. For some patients C-reactive protein level may more closely parallel their clinical course than ESR.

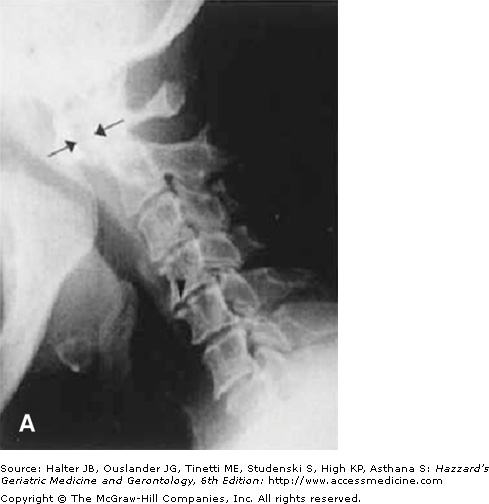

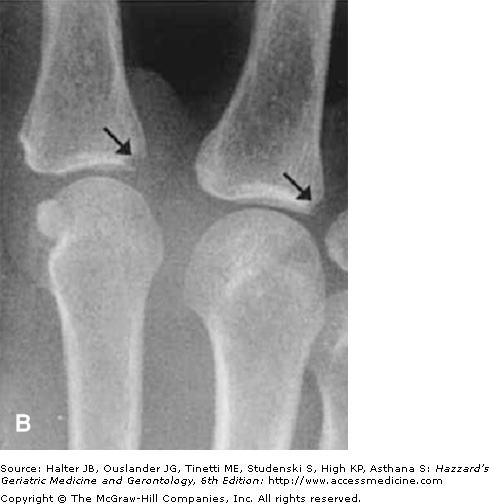

Radiographic joint examination is an integral part of the evaluation of patients with RA. Elderly patients with RA for more than 10 years are at particular risk of cervical spine disease and atlantoaxial joint instability. This is an important consideration before a patient is submitted to a surgical procedure, as overextension of the cervical spine during intubation may compromise the brainstem or spinal cord. Early x-ray changes include soft-tissue swelling and regional osteoporosis around the joint. Typical erosions in hands and feet involve the juxta-articular “bare areas” of bone not covered with cartilage (Figure 120-3). Isolated erosions in the first and second metacarpophalangeal joints may prompt the clinician to search for occult calcium pyrophosphate depositive disease, hyperparathyroidism, or hemochromatosis. Erosions are less common in the knee and hip joints. At these sites, RA typically causes cartilage loss and joint-space narrowing. Joint-space narrowing occurring predominantly in the lateral compartment of the knee and diffusely in the hip without bony proliferation is helpful features for distinguishing RA from osteoarthritis. To assess for joint-space narrowing of the knees, clinicians should request semiflexed weight-bearing films.

Figure 120-3.

Radiographic changes of rheumatoid arthritis. (A) x-ray of the cervical spine in the flexed position showing severe atlantoaxial joint subluxation in a patient with chronic rheumatoid arthritis, with arrows highlighting the abnormal distance between the posterior surface of the anterior arch of the atlas and the anterior surface of the odontoid process. Arrowhead points to the erosion on the surface of C5. (B) Early erosive changes in the metacarpal phalangeal joints affecting the “bare area” of the bone not protected by cartilage. (C) Bilateral hand x-ray with advanced rheumatoid arthritis. Some of the features include juxta-articular osteoporosis, collapse of the carpal bones, radial deviation of the radiocarpal joint of the wrist (arrows), and erosion and destruction of metacarpal phalangeal joints (arrowheads). Note also the symmetric nature of the disease. (Courtesy of Curtis Hayes, MD, University of Michigan.)

Because of the limitation of clinical examination in detecting subtle signs of inflammation, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging have been used for detecting synovitis. It is clear that these modalities are extremely sensitive for detecting active inflammation. One study found that the majority of patients with treated disease and considered by their physicians to be in remission continued to have magnetic resonance imaging evidence of active synovitis. The unanswered question is whether more aggressive treatments of patient with clinically inactive disease but imaging evidence of ongoing synovitis affect patient outcomes such as long-term disability. Elderly patients with RA have additional facets that need to be taken into consideration, such as a more limited lifespan and greater infection risk with immunosuppression. At this point, the utility of these sensitive imaging modalities in clinical practice is undefined.

There is no evidence that patients with EORA are more likely to develop extra-articular disease, as compared to those with YORA. However, the elderly population may be disproportionately affected because extra-articular manifestations are more common in chronic RA. High titer of RF is a risk factor for extra-articular RA, especially in male patients. Rheumatoid nodules are the most characteristic extra-articular manifestation of RA and are present in up to 40% of seropositive white patients. These are most commonly found in areas of pressure such as the elbows, heels, and sacrum. Their presence does not correlate with disease activity and may increase in number during methotrexate therapy when synovitis is improving. Rheumatoid vasculitis affects vessels of all sizes. This complication may present as cutaneous vasculitis, mononeuritis multiplex, nail fold infarcts, or deep “punched-out” ulcers at atypical sites that fail to respond to conventional therapy. Pleuritis and pericarditis are found in 20% to 30% of patients with RA and do not usually cause any symptom. Other respiratory complications of RA include pulmonary granuloma (often in the upper lobes), Caplan’s syndrome, fibrosing alveolitis, and bronchiolitis obliterans. Felty’s syndrome (RA with splenomegaly and neutropenia) typically occurs in white patients with long-standing, chronic erosive RA. These patients are at increased risk of developing lymphoproliferative malignancies. Thrombocytopenia may occur, in part, because of splenic sequestration. Mild-to-moderate normochromic, normocytic anemia is extremely common in patients with chronic RA. Iatrogenic causes (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] and methotrexate) of anemia need to be excluded in all patients with RA who have anemia.

Successful management of RA involves patient participation in his/her care. In addition, family, social, and psychological supports are particularly critical in maintaining the older RA patients’ independence. Older patients diagnosed with the disease may be particularly fearful of what it means to their independence or may become depressed. Establishing a good rapport, gaining the trust of the patient and the family, providing information about the nature of the disease, and setting realistic goals are all important elements of the initial management of RA. Many patients and their relatives also find it helpful to seek out support groups in their local area. Increasingly, elderly patients and their families are turning to the Internet, health magazines, and other nontraditional sources for information about treatment options, including over-the-counter complementary therapies. It is important that health-care professionals be aware of the pros and cons of these options. In this regard, resources such as The Arthritis Foundation’s Guide to Alternative Therapies can be helpful. Unfortunately, the unexpected side effects of over-the-counter medications are increasingly being recognized. The latest information is often not available in traditional textbooks. Directing the patients to reputable websites such as that offered by the National Institute on Aging can be useful for more up-to-date information.

Nonpharmacologic therapies are crucial components of the total care of the patient with RA, which should be emphasized throughout the treatment course. In addition to their inherent usefulness, participation in these treatment modalities often provides the patients and their families with a sense of control over their chronic illness. The team approach that typifies geriatric medicine is eminently suitable for treating elderly patients with chronic arthritis. Physical and occupational therapy should be offered to every patient with RA, including those with mild and early disease. Education about rest/activity, use of cold/heat, massage, adaptive devices (to improve function and to prevent/correct joint deformity) are important. Performing exercises to strengthen muscles and ligaments for joint protection, gait training, and fall prevention can make a big difference in the life of patients with RA. Community-based exercise programs such as PACE (Patients with Arthritis Can Exercise, the Arthritis Foundation) are a good resource for those who are able to participate. Psychological counseling and support groups are often helpful, especially to those who are socially isolated because of their arthritis. Depression is increasingly recognized as a common problem in the elderly and in those with chronic illness. Adequate treatment will help break the vicious cycle of pain, depression, and disability. Although nonpharmacologic therapies have not been shown to affect the course of RA, these can improve the patient’s quality of life and help to reduce the requirement for pain medications that have significant potential for side effects in this vulnerable population.

Recent years have seen an exciting explosion of new drugs available for the treatment of RA. Pharmaceutical companies have increasingly included the geriatric population in pre- and postmarketing clinical trials. Although this provides some reassurance to clinicians, knowing that these agents may be efficacious in the elderly population, it is important to remember that subjects participating in these studies rarely mirror the patients geriatricians see in their clinic who have multiple comorbidities and who already suffer from polypharmacy. The costs of these new agents may be out of reach for patients who do not have prescription coverage. Because of the complexity of modern treatment regimens, coupled with the need to monitor many potentially serious side effects, drug therapy for RA should ideally be instituted in consultation with a rheumatologist. Involvement of physicians experienced in the use of immunosuppressive therapies (e.g., hematologists and oncologists, or a gastroenterologist in the case of infliximab) will be helpful in patients living in isolated communities where there may not be a local rheumatologist.

The gradualism of the “pyramid approach” to RA treatment in the 1980s has been replaced with the widespread belief that rheumatoid inflammation should be suppressed as completely and as soon as possible once the diagnosis is confirmed. This change in philosophy is, in part, a result of the recognition that joint damage occurs much sooner than was previously believed. Results of well-designed clinical trials in the past decade have persuaded many that this new standard is attainable with more aggressive drug regimens. In the ACR updated 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis, it is suggested that the majority of patients with newly diagnosed RA should be started on disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy within 3 months of diagnosis.

Although NSAIDs are useful adjunct therapies for RA, many geriatricians are reluctant to prescribe this class of medication because of concern that elderly persons are vulnerable to the potential serious toxicity that can occur in almost every major organ system in the body. Meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990s found that NSAID use is associated with a 5- and 3.5-fold increased risk of serious upper GI tract disease in women and men, respectively. Age alone is a risk factor for upper GI bleeding (relative risk of 4.5 in 70–80 years age group, and 9.2 in those older than age 80 years). Because of the high background rate of upper GI events in the elderly population, the relative risk for GI bleeding only increases modestly in elderly patients on NSAID. Not surprisingly, elderly patients with history of GI bleeding are at the greatest risk of serious GI complications when they are placed on an NSAID. The concurrent use of glucocorticoids further increases the risk of GI bleeding.

The use of selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors has decreased substantially in recent years when it was discovered that some of these agents are associated with an increased incidence of cardiac events in large population studies. In addition, COX-2 inhibitors shares similar renal toxicity, including hypertension, peripheral edema, and rising serum creatinine as traditional NSAIDs. Chronic use of these agents should, therefore, be avoided when possible. NSAID-induced renal complications are more likely to occur in patients who are on concurrent diuretics or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. One study showed that prolonged dosing of ibuprofen blocked the platelet inhibition effects of aspirin. Although other NSAIDs tested so far do not appear to have the same problem, this raises the concern that the aspirin/ibuprofen combination may not be ideal for patients having RA with cardiovascular risk factors. Concurrent use of low-dose (≤325 mg/day) aspirin increases the already high risk for GI events in elderly patients taking traditional NSAIDs and may negate most of the GI-sparing effect of COX-2 inhibitors. At present, it appears that most at-risk elderly patients with RA requiring a traditional NSAID or a COX-2 selective agent plus aspirin should receive GI cytoprotection.

Low-dose glucocorticoid is effective for short-term symptom control in patients with active RA. There are also intriguing data showing that prednisone in early disease may be “disease modifying.” Unfortunately, elderly patients commonly develop significant side effects but become functionally dependent on the drug. The lowest dose, and, if possible, alternate-day dosing should be prescribed. Assessment, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis, cardiovascular risk factors, diabetes, and GI complications are important. Judicious use of intra-articular steroid injections may provide local (and systemic) symptom relief and may be safer than oral glucocorticoids in elderly patients with poorly controlled diabetes, severe osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.

Antimalarials including hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine are useful in mild cases of RA and are most often prescribed as part of a combination regimen. Hydroxychloroquine is often preferred over chloroquine because it has a lower incidence of ocular complications. Approximately 50% of hydroxychloroquine is protein bound in the plasma, a property that is important in elderly patients with low serum albumen and who are taking other highly protein-bound drugs. The mechanism of drug action is uncertain but is postulated to include changes in intracellular pH, which, in turn, affect antigen presentation by immune cells. An added benefit in patients with RA who are at increased risk of coronary heart disease is the drug’s favorable effect on serum cholesterol level. There are also intriguing new data suggesting that patients with RA on hydroxychloroquine have up to 77% less risk of developing diabetes. The major side effect of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine is retinal (macular) toxicity with the classical “bull’s-eye” lesion. The patients most susceptible to this complication are those older than 70 years who are on >6.5 mg/kg daily dose or who have a cumulative dose of >800 g of the drug. Elderly patients with macular degeneration or inoperable dense cataract are not candidates for this drug.

Sulfasalazine is only occasionally used as monotherapy in the United States, although there are data showing that the drug may slow the progression of radiographic damage in RA. Its mechanism of immunosuppression is unclear but may include reducing immunoglobulin (Ig) levels, suppressed T- and B-cell proliferative response, and cytokine inhibition. Cytopenias (particularly leukopenia), GI symptoms (nausea and vomiting, and dyspepsia), and skin rashes are the commonest side effects. In addition to monitoring for hematologic toxicity, some experts recommend that liver enzyme levels should be tested regularly as well.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree