Advances in the treatment of primary rectal cancer, including total mesorectal excision (TME) and neoadjuvant chemoradiation, have reduced the local recurrence (LR) rate to approximately 10% in the modern era.1–3 While the LR rate following resection of rectal cancer significantly exceeded that of colon cancer in older publications, the two are now roughly equivalent.4–6 Given the present incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in Western countries of approximately 130,000 cases annually,7 the burden of LR nevertheless remains significant.

Without treatment, the median survival from time of detection of LR is approximately 3 to 9 months.8,9 With palliative chemotherapy and/or radiation median survival is approximately 17 months.10–12 Surgical resection, in combination with other modalities, can achieve prolonged survival and even cure in appropriately selected patients. With radical extirpation, 5-year overall and recurrence-free survival rates of approximately 50% have been published in recent series.13–19

Greater attention to technical detail, patient selection, and multidisciplinary care has improved the management of patients with recurrent CRC. Increasingly complex patients are now being treated with curative intent. However, there is limited good-quality evidence available from the literature on recurrent CRC, which consists mainly of retrospective case series that focus on locally recurrent rectal cancer (LRRC). This chapter reviews the literature and provides an approach to the assessment and management of patients with locoregional recurrence of colorectal cancer. We will focus on LRRC, with mention of recurrent colon cancer where relevant.

There is a greater risk of LR in men than women.20 Both T and N status predict LR.21,22 A positive circumferential margin of resection portends a higher risk of LR.20,21 The advent of TME has been associated with a significant improvement in circumferential margin status, and many surgical series document this relationship.20,23–25

Advanced histopathologic stage is the most significant risk factor for LR following resection of primary colon cancer.26 Poorly differentiated tumors have a higher risk of LR compared to well- and moderately differentiated colon cancers. Distal colon cancers have been associated with a higher risk of LR, in some but not all studies.27,28

The overexpression of the tumor suppressor protein p53 by rectal cancers has been associated with a high rate of LR after resection and chemoradiation of the primary tumor.29 In one series, rectal cancers that had both increased p53 nuclear accumulation and decreased expression of Bcl-2, which is inhibited by p53, had the highest risk of LR.30

CD133 and CD44 have been identified as potential cancer stem cell markers for CRC and other malignancies.31 In one study, these markers showed a trend toward being higher in primary rectal cancer specimens from patients who later developed a locoregional recurrence.

Despite clinical and imaging surveillance, symptoms were present and led to the diagnosis of LR in 65% to 67% of patients with rectal cancer and 52% of patients with colon cancer in retrospective series.32–34 Patients with a LR of CRC most commonly present with abdominal, back, or flank pain, or rectal bleeding. The presence of rectal discharge, a change in bowel habits, malaise, nausea and vomiting, or other obstructive symptoms should also suggest the possibility of LR.22,32 The development of new genitourinary or lower extremity neurologic symptoms may be the first manifestation of a pelvic recurrence. Any new symptoms should prompt a full functional inquiry, physical examination, and further investigations.

Review of symptoms with particular attention to new pain and gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and/or neurologic symptoms should be undertaken and recorded in detail. Functional inquiry should establish performance status and ability to tolerate various treatment modalities. Physical examination should focus on the abdomen and pelvis, with rectal examination, and pelvic examination in women. Groin, axillary, and neck adenopathy should be sought and documented. Lower extremities should be examined for motor and sensory functions. A general physical examination, including cardiorespiratory function, is also advisable.

Indicators of hematologic, hepatic, renal, and nutritional status should be examined to assess suitability for active treatment. The CEA level is compared to previous, and also serves as a baseline for future comparison.35

Endoscopic examination of the anastomosis or rectal stump, with biopsy, should be performed to assess luminal involvement, with the recognition that the majority of pelvic recurrences do not penetrate intraluminally. Full colonoscopy is also indicated to assess for new primary tumor elsewhere.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be done to assess for regional adenopathy and distant metastatic disease,36 as well as structural manifestations of locally recurrent disease such as hydroureter, bowel obstruction, and invasion of surrounding structures. In difficult cases, comparison of cross-sectional imaging to baseline indices early after primary resection is particularly helpful.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis should be done if there is suspected or confirmed LR. MRI enables more accurate assessment of the extent of LR and allows for detailed surgical planning. Recurrent tumor size, location, and extension into adjacent pelvic organs and structures can be accurately assessed by MRI.15,36,37

Positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) is indicated in selected patients undergoing investigation for LR. It is indicated when CEA is elevated but a standard workup fails to identify the site of recurrence, or when CT or MRI are not definitive for the presence of metastatic disease.38 It may also be useful for discriminating between fibrosis and tumor recurrence,39 although false-positive and false-negative results can occur, even with expert interpretation.

A biopsy of the suspected area of recurrence, based on imaging, may be obtained to confirm LR histopathologically. However, evidence of progression on serial imaging, especially with an elevated CEA or positive PET-CT, is highly suggestive of a recurrence and may substitute for the pathologic diagnosis.13,36 Assessment and management in such cases should be undertaken following discussion at a multidisciplinary case conference36 to minimize the possibility of radical treatment for an entity that is not recurrent colorectal cancer.

Cystoscopy can show frank invasion of pelvic recurrence into the bladder lumen, but a negative cystoscopy does not rule out significant extrinsic penetration of the bladder wall. This is better assessed on MRI.

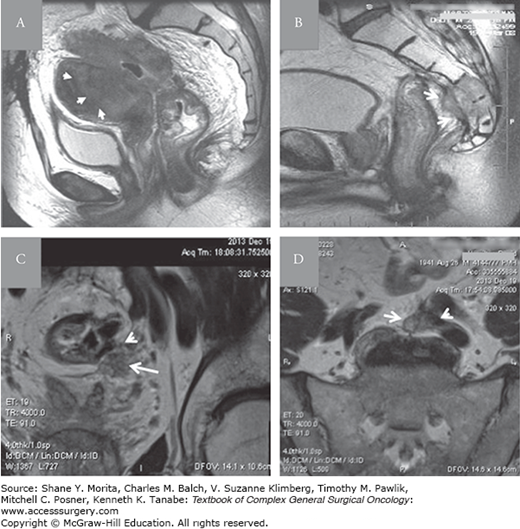

A number of schemes have been proposed for the staging of LRRC, and there is currently no agreement on which system is most useful. Selected representative schemes are shown in Table 114-1. The ideal system would be based largely on variables that can be ascertained preoperatively, chiefly through imaging, and would allow accurate prediction of attaining R0 status, which is the most consistent predictor of re-recurrence and survival (see the section on Prognosis Following Resection). Pelvic MRI is the cornerstone of preoperative classification and also guides the operative strategy (Fig. 114-1). Preoperative staging should also identify the presence of distant metastatic disease, typically assessed by CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which can be supplemented by PET scan as indicated (see the section on Diagnostic Evaluation of Suspected Locoregional Recurrence). The majority of proposed classification schemes for LRRC discriminate central pelvic recurrences from those involving the lateral pelvic sidewall and include a category for presacral/sacral involvement. Lateral and sacral recurrences have been associated with decreased rates of R0 resection and increased rates of re-recurrence, according to many authors.40,41 Lateral recurrences have also been associated with decreased overall and cancer-specific survival.40,42 While negative margins can be achieved with well-planned sacral resections,43 obtaining an R0 resection in the case of lateral recurrence is more challenging because of several anatomical and technical reasons. Moreover, resection of lateral recurrence is typically associated with higher risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality.40,44

Classification Schemes for Locally Recurrent Rectal Cancer

| Authors | Classification | Definition | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyle et al34 | Central | Tumor confined to pelvic organs or connective tissue without contact onto or invasion into bone |

| |

| Sacral | Tumor present in the presacral space and abuts onto or invades into the sacrum | |||

| Sidewall | Tumor involving the structures on the lateral pelvic sidewall, including the greater sciatic foramen and sciatic nerve through to piriformis and the gluteal region | |||

| Composite | Sacral and sidewall recurrence combined | |||

| Guillem and Ruo47,a | Axial | Not involving anterior, posterior, or lateral pelvic walls; includes anastomotic recurrence after low anterior resection, local recurrence after transanal or transsphincteric excision, and perineal recurrence after abdominoperineal resection |

| |

| Anterior | Involving the urinary bladder, vagina, uterus, seminal vesicles, or prostate | |||

| Posterior | Involving the sacrum and coccyx | |||

| Lateral | Involving the bony pelvic sidewall or sidewall structures including the iliac vessels, pelvic ureters, lateral lymph nodes, pelvic autonomic nerves, and sidewall musculature | |||

| Suzuki et al48,b | Symptoms |

| ||

| S0 | Asymptomatic | |||

| S1 | Symptomatic without pain | |||

| S2 | Symptomatic with pain | |||

| Degree of fixation | ||||

| F0 | No site | |||

| F1 | One site | |||

| F2 | Two sites | |||

| F3 | Three or more sites | |||

FIGURE 114-1

Representative MRI images of LRRC classified according to scheme presented in Table 114-2: A. Central and anterior perianastomotic recurrence invading the uterus (arrows). B. Central and posterior recurrence invading the sacrum (arrows) following an abdominoperineal resection. Coronal (C) and axial (D) lateral and posterior recurrence (arrow) invading the left external iliac vein and obstructing the left ureter (arrow head).

Many of the published classification schemes for LRRC were derived from intraoperative findings at exploratory laparotomy and/or postoperative pathologic findings. With the widespread use of high-quality MRI and more educated interpretation of the same, the “discovery” aspect of laparotomy has been minimized, and one does not expect to rely on multiple intraoperative frozen sections to define the extent of disease.

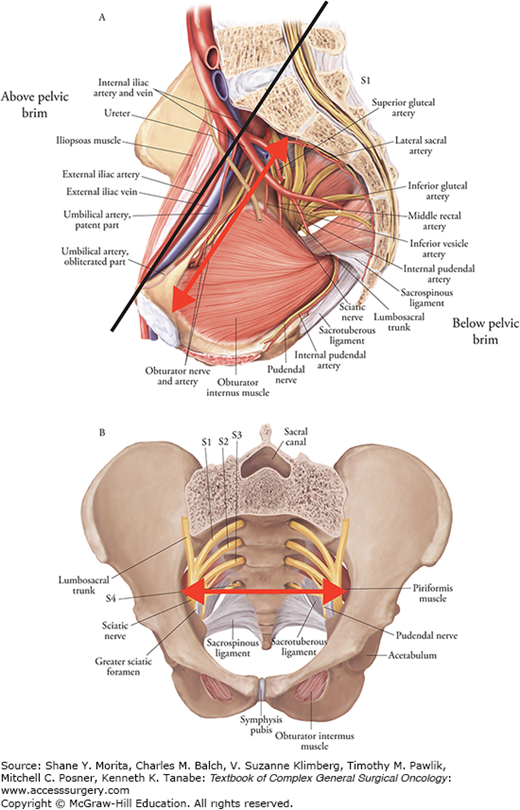

We utilize a pragmatic classification system that relies on MRI evaluation of location and involved structures (Figs. 114-1 and 114-2, Table 114-2). The fundamental distinction is between tumor location above, versus below, the pelvic brim, with further segmentation of tumors confined below the brim into central versus lateral categories along an anterior-posterior axis. This system is based on difficulty of attaining R0 margin of resection, with compounding of difficulty mandating ever greater positive patient factors (i.e., fitness, supports).

Proposed Classification Scheme for Locally Recurrent Rectal Cancera

| Location | Structures Involved | Resection |

|---|---|---|

| Below Pelvic Brim | ||

| Central Only | Colorectal anastomosis/rectal stump, bladder, vagina, uterus, prostate, seminal vesicles | Redo low anterior resection, abdominoperineal resection, multivisceral resection, or pelvic exenteration |

| Central and Anterior-Posterior | Central plus pubic symphysis anteriorly, sacrum and coccyx posteriorly, sacral nerve roots |

|

| Lateral Only | Internal iliac vessels, external iliac vessels, ureter, sciatic nerve, obturator internus, piriformis, obturator nerve and vessels, sacral nerve roots | Selected cases |

| Lateral and Anterior-Posterior | Lateral plus pubic symphysis anteriorly, sacrum and coccyx posteriorly, sacral nerve roots | Highly selected cases |

| Above Pelvic Brim | Common iliac vessels, aorta, vena cava, ureter, femoral nerve, psoas, iliacus, small bowel, lumbar spine | Highly selected cases |

Locoregional recurrence of colon cancer has likewise been classified by a number of schemes, though there is no widely accepted system. Representative examples are provided in Table 114-3. The scheme proposed by Harji et al50 is analogous to several of the LRRC classification schemes, while that proposed by Bowne et al32 is comprehensive and correlates with prognosis.

Classification Schemes for Locally Recurrent Colon Cancer

| Authors | Classification | Definition | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowne et al32 | Perianastomotic | Occurring at the anastomosis |

|

|

| Mesentery/Nodal | Tumor present in the mesentery of nodal basin | |||

| Retroperitoneum | Tumor involving the retroperitoneum | |||

| Peritoneum | Peritoneal deposits or carcinomatosis | |||

| Harji et al50 | Anastomotic | Occurring at the anastomosis |

| |

| Abdominal | Divided into nodal, anterior abdominal wall, and retroperitoneal | |||

| Pelvic | Divided into anterior, lateral, central, and posterior |

Given that patients have been previously irradiated and the surgical planes distorted during the primary operation,13 modified strategies must be utilized in the management of patients with LRRC.

The locally advanced nature of many of these recurrences has pushed surgeons to explore techniques used in the treatment of other malignancies, such as retroperitoneal sarcomas and primary spinal malignancies, and apply these techniques to LRRC.

The most fundamental decision is whether to attempt curative resection, and this must be predicated on the expected oncologic outcomes as well as a variety of other factors (see the section Decision-making below). Table 114-4 shows outcomes and prognostic factors in patients undergoing surgery for LRRC since 1994, as presented in retrospective case series published between 2004 and 2016. The most consistently important prognostic factor identified is margin status, with R0 resection portending improved local control and survival. Thus the prime directive is to obtain R0 status, and to offer resection only when it appears feasible. Pelvic sidewall involvement, preoperative pain, and a lack of radiation treatment have been associated with inferior R0 resection rates.13,41

Retrospective Case Series Published during 2004 to 2016a

| Study | Resected (n) | R0 (n, %) | Outcomes (Entire Cohort) | Outcomes for R0 | Prognostic Factors for Survival (p < 0.05) | Prognostic Factors for R0 Resection (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moore et al (2004)41 | 119b | 61 (51%) | Pelvic sidewall, ureteric, or iliac vessel involvement (−) | |||

| Wells et al (2007)43 | 52 | 41 (79%) |

| Margin status | ||

|

| M1 (−) | ||||

| ||||||

| Dresen et al (2008)13 | 147 | 84 (57.2%) |

|

| Margin status | Radiation treatment (+) |

|

| Radiation treatment (+) | Pain (−) | |||

|

| Stage of primary | ||||

| Sagar et al (2009)37 | 40 | 20 (50%) |

| Margin status | ||

| You et al (2011)51 | 75 | Margin status | ||||

| Pain severity (−) | ||||||

| Rahbari et al (2011)52 | 92 | 54 (58.7%) |

|

| Margin status | |

| M1 (−) | ||||||

| Bhangu et al (2012)53 | 70 | 45 (64%) |

| Margin status | ||

| Median survival not reached at 3 years | M1 (−) | |||||

| Number of involved compartments (−) | ||||||

| You et al (2016)19 | 229 | 184 (80.3%) | 5-year OS 41.6% | 5-year OS 50.4% | Margin status | |

| 5-year DFS 47.3% | Secondary failure (−) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree