Radiologic Evaluation of the Head and Neck Cancer Patient

Jeffrey A. Bennett

INTRODUCTION

Cross-sectional imaging studies are an essential part of the care of the head and neck cancer patient, from initial diagnosis and staging to surveillance for cancer recurrence. This chapter will begin with a general discussion of normal imaging anatomy because this knowledge is very important for interpretation of the images. The appearance of pathology will then be addressed with emphasis on what needs to be in the radiology report. This includes a description of the full extent of the primary tumor, including which anatomic spaces of the head and neck are involved, whether or not there is bone or cartilage invasion, and whether there is perineural or perivascular spread of disease. What makes a lymph node positive or suspicious for cancer will be addressed, including extracapsular spread of disease and involvement of the dermal lymphatics. Finally, the identification of distant metastatic disease will be discussed. This approach to imaging is fundamental to the accurate staging of cancer and appropriate treatment, so that there will be no surprises at surgery and so that radiation portals can be optimally created. The pros and cons of the available imaging techniques, primarily computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET), will be discussed throughout the chapter. The reader is referred to the site-specific chapters in Section 2 for suggested CT and MRI protocols and imaging concerns specific to disease in those locations.

IMAGING ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Nasopharynx

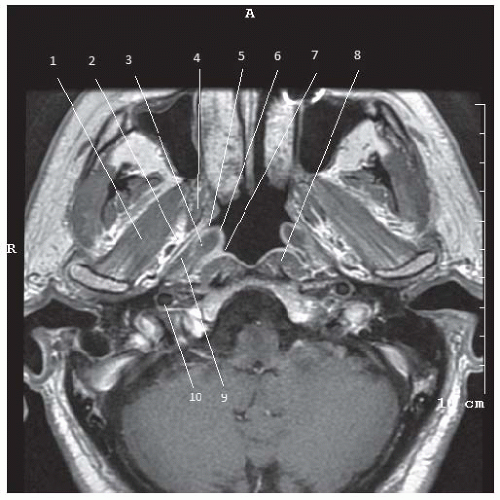

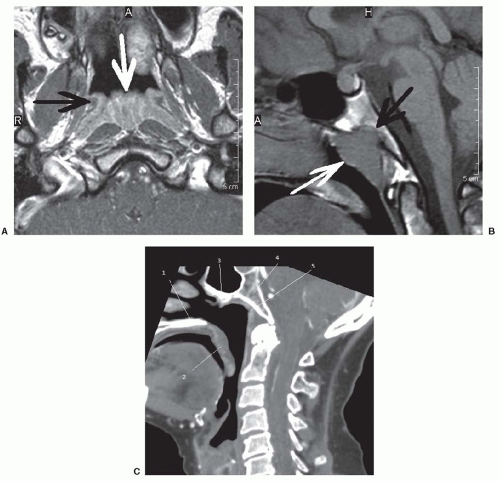

The nasopharynx (Fig. 4-1) is the epithelium-lined most superior aspect of the pharynx and is supported and held open by the rigid and strong pharyngobasilar fascia. The superior boundary is the skull base at the floor of the sphenoid sinus and the upper portion of the clivus (Fig. 4-2). Anterolaterally are the medial pterygoid plates. The inferior boundary of the nasopharynx is at the level of the hard palate where it merges with the oropharynx. Anteriorly the nasopharynx is continuous with the nasal cavity by way of the posterior choanae. Posteriorly the nasopharynx is bordered by the retropharyngeal space, and posterior to that is the prevertebral space. Laterally the nasopharynx is separated from the fat-filled parapharyngeal space by the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle and palatal muscles. The pharyngobasilar fascia is medial to the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle and tensor veli palatini muscle. The levator veli palatini muscle is medial to the pharyngobasilar fascia and attaches to the Eustachian tube.

The torus tubarius is seen on axial sections at the level of the mid- and upper nasopharynx. It is made up of the distalmost part of the cartilaginous portion of the Eustachian tube, whose orifice is just anterior to the torus tubarius. The Eustachian tube and the levator veli palatini muscle pass through an opening in the pharyngobasilar fascia called the sinus of Morgagni. This opening in the fascia provides a potential conduit for spread of nasopharyngeal carcinoma into the parapharyngeal space and to the central skull base.1 The Eustachian tube connects the nasopharynx to the middle ear. In close to 50% of patients with a nasopharyngeal mass, the Eustachian tube becomes obstructed, leading to serous otitis media.2 Thus, a finding of middle ear and mastoid opacification should prompt a search for a nasopharyngeal obstructive mass (Fig. 4-3).

The fossa of Rosenmüller is a mucosal recess located posterior to the tori and lateral to the flexor muscles of the neck, the longus coli and longus captitus muscles, which lie in the prevertebral space. Tumors that originate in the fossa of Rosenmüller are often clinically occult.

Along the roof of the nasopharynx are the adenoids, or nasopharyngeal tonsil. This lymphoid tissue varies in appearance with age (Fig. 4-2), normally involuting by age 30, but can remain prominent in smokers and in patients with HIV.3 As it appears similar in density to carcinoma on CT, when the finding is made of apparent lymphoid tissue infiltrating into the adjacent deeper tissue planes, a tumor should be suspected, as normal lymphoid tissue does not do this.

There is an extensive submucosal capillary lymphatic plexus in the nasopharynx, which explains the high incidence of positive lymph nodes in cases of nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.4 Primary drainage is to the retropharyngeal lymph nodes and level 2 nodes.

The lateral retropharyngeal nodes of Rouviere lie in the retropharyngeal space medial to the carotid sheath and lateral to the flexor muscles of the neck. One to three nodes can normally be present on each side, usually at the level of C1, but they can be seen as low as the level of C3. The retropharyngeal nodes atrophy with age, possibly because of frequent upper airway infections in childhood. Normal retropharyngeal nodes in children measure 10 mm ± 2 mm and in adults measure 5 mm ± 2 mm (Fig. 4-4).

Oropharynx

The oropharynx (Fig. 4-5) is bounded anterolaterally by the anterior tonsillar pillars, inferiorly by the pharyngoepiglottic folds, and superiorly by the soft palate, which is considered part of the oropharynx. The palatine tonsils are contained in the oropharynx as are the glossotonsillar sulci, which connect the lateral oropharyngeal wall with the tongue base. The anterior tonsillar pillar is made up of mucosa covering the palatoglossus muscle, whereas the posterior tonsillar pillar is made up of mucosa covering the palatopharyngeus muscle. In between these pillars is the tonsillar fossa containing the partially encapsulated palatine tonsil. This contains a variable amount of lymphoid tissue from side to side as well as with age. Lateral to the palatine tonsil is the fat-filled parapharyngeal space. This space gets smaller in its more inferior aspect where it communicates freely with the submandibular space.

The posterior third of the tongue, referred to as the tongue base, is also contained in the oropharynx. It extends from the circumvallate papillae to the vallecula. The mucosa of the vallecula and the anterior surface of the free margin of the epiglottis is part of the oropharynx, whereas the mucosa over the posterior surface of the free margin of the epiglottis is included in the supraglottic larynx (Fig. 4-6).

The lingual tonsil is incorporated into the mucosa of the tongue base. Like the adenoids and palatine tonsils, this lymphatic tissue has increased prominence with younger age and in smokers.

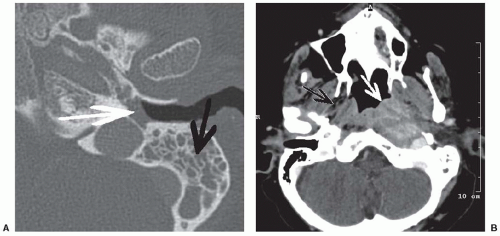

The Oral Cavity and Floor of the Mouth

The oral cavity consists of the lips, anterior two-thirds of the tongue, and the hard palate. The hard palate and soft palate are best evaluated with imaging in the coronal plane. Also best evaluated in the coronal plane is the floor of the mouth, which lies between and includes the mucosa of the floor of the mouth and the mylohyoid muscle (Fig. 4-7). The mylohyoid muscle attaches to the mylohyoid line of the mandible and posteriorly to the hyoid bone. It is a U-shaped muscle with a median raphe in the midline and creates an opening posteriorly.

The submandibular space, actually part of the suprahyoid neck, is located below the mylohyoid muscle, although the submandibular gland itself extends around the posterior edge of the mylohyoid to enter the sublingual space in the floor of the mouth.

The genioglossus muscles, which are extrinsic muscles of the tongue, and the geniohyoid muscles attach to the genial tubercles on the lingual surface of the mandible. Between these paired muscles is the midline septum of the tongue. The sublingual space containing the sublingual gland is located between these muscles and the mylohyoid. The submandibular duct, lingual nerve, and hypoglossal nerve all course through the sublingual space. The sublingual gland and lingual nerve, which is a branch of V3, course lateral to the hyoglossus muscle, whereas the lingual artery and vein and the hypoglossal nerve are medial to the hyoglossus muscle (Fig. 4-8). The lingual artery supplies blood to the tongue, with the lingual septum preventing much anastomosis across the midline.

The buccal mucosa is the mucosa of the cheek. The buccinator muscle lies deep to the mucosa and attaches to the maxillary alveolar ridge, the body of the mandible, and posteriorly inserts on the pterygomandibular raphe. The pterygomandibular raphe is a thick, vertically oriented fibrous band that also serves as the insertion of the orbicularis oris and superior constrictor muscles. It serves as a relative barrier to the spread of cancer. It lies deep to the mucosa of the retromolar trigone, which is the triangular mucosal surface behind the third mandibular molars and covers the ascending ramus of the mandible (Fig. 4-9). A surgical landmark superior to this region is the maxillary tuberosity, which is a bony bulge behind the third maxillary molar.

The mucosa covering the lingual alveolar surface and buccal alveolar surface of the maxilla and mandible is called the gingiva. The junction between the gingiva and buccal mucosa is called the upper and lower gingivobuccal sulcus, respectively, and is a common location in the oral cavity for squamous cell carcinoma to arise (Fig. 4-10).

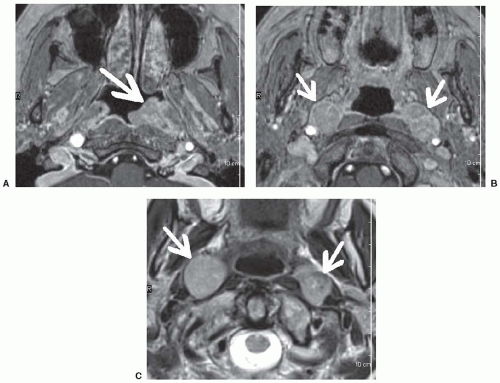

The Suprahyoid Neck

The compartmental organization of the neck is based on the superficial and deep fascial layers. On imaging studies, the fascia itself usually blends in with the structures it surrounds such as muscles and blood vessels.5 However, fat contained in the spaces created between fascial boundaries is of low attenuation on CT scans and high signal compared to muscle on T1-weighted and fast spin echo T2-weighted images, and thus provides contrast that is very helpful for the localization of masses. The prestyloid parapharyngeal space, for example, contains mostly fat, although it also contains the ascending pharyngeal neurovascular bundle

and the tensor muscle of the palate. This fat is easily visualized on imaging studies and will be displaced laterally by a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal mass, medially by a masticator space mass, and anteriorly by a retrostyloid parapharyngeal space mass (Fig. 4-11).

and the tensor muscle of the palate. This fat is easily visualized on imaging studies and will be displaced laterally by a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal mass, medially by a masticator space mass, and anteriorly by a retrostyloid parapharyngeal space mass (Fig. 4-11).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree