6.1 Introduction

This chapter focuses on the best approaches to developing effective interventions at the individual level. Chapter 5 covered ecological level interventions. The distinction between an ecological (groups, communities or whole population) and an individual-level intervention is the level at which the intervention is targeted, and thus also the level at which the impact is evaluated. To some extent, the desire to use an ecological rather than an individual approach arises out of a broader perspective of health, with a desire to address the basic and underlying causes of problems. The ecological approach accepts that health is determined not solely by an individual’s behavior, but by an interaction between an individual and the wider environment. Even if an individual wants to change their behavior they may be constrained by wider socioeconomic factors. An individual approach fits more comfortably with a narrower view of public health that seeks to address risk factors at an individual level and focuses on removing illness.

In this chapter the focus is on interventions at the individual level. These interventions are likely to be more effective if supported by a consideration of the wider social, economic and political context in which the individuals live their lives. Interventions can vary from the simple provision of information to intense individual support. The choice of the intervention most likely to be effective will depend on the target group. Several interventions may be used to reinforce the message that is trying to be communicated. However, if people cannot afford to do what is being asked, or they do not have the skills required, it will be unlikely that the intervention will be effective or sustainable.

Possible approaches to intervention

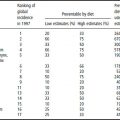

Having identified what the problem is, and defined a goal and targets (as outlined in Chapter 1), the aim should be to develop a program of work that will be most effective in achieving the required change. Before starting work the aim should be to weigh up the pros and cons of all the different potential programs of work, and then select the most effective approach or approaches. It is somewhat artificial to separate out the individual and ecological approaches as it is likely that a mixture of both may be most effective. For example, if a program is aimed at improving the quality (nutrient density) of a diet the options for the program may include education to improve knowledge, attitudes and perceptions, skills to allow previously uneaten foods to be consumed, food-based intervention, supplementation, food fortification, income to reduce economic constraints, and improved physical access to foods (price and availability). Food fortification, income and price policies may be considered as ecological interventions, because they do not directly target each individual, but aim to change the whole population. Interventions to improve knowledge and skills, or food-based interventions or supplementation may be seen as individual-level interventions because they target the individual. It is always helpful to review previous research to identify which approaches have been shown to work.

Some problems may be conducive to an ecological or population approach. Perhaps the best example internationally is the fortification of salt with iodine, and more recently bread or flour with folate or other micronutrients. Another population approach that is gaining support is for food manufacturers to reduce the salt or sugar or fat content of foods; none of the changes requires any effort, or even awareness, on the part of individuals. There is a philosophical divide as to whether the food supply should be manipulated by producers (either under regulation or not) to change levels of consumption. As highlighted in Chapter 5, programs aimed at increasing the desire by individuals to eat more fruits and vegetables will not be effective unless the desire can be translated into action by the foods being available (physical and economic access).

It should not be assumed that the only approach to achieving change is by attempting to change knowledge or attitudes in an individual. Nor can it be assumed that these are the major constraints to individuals making changes to their diet or level of physical activity without evidence. Caution should always be exercised in generalizing from one population or subgroup to another, and the interplay of factors may be quite different. It may also be important to consider where the push for change comes from: is it bottom–up or top–down. Is it addressing a perceived need, or is it motivated by cost (promoted by a government to save money) or an ideological perspective?

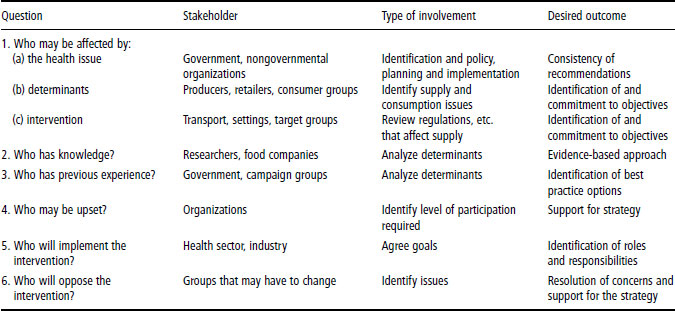

It is essential to consider all of the stakeholders that may need to be involved or who could have an influence on the effectiveness of the intervention (Table 6.1).

The rest of this chapter will focus on past experience and summarize what is known about the most effective approaches to achieving change at the individual level, within a public health rather than a clinical context. Examples will be taken from three important reviews (Roe et al., 1997; Allen and Gillespie, 2001; Eurodiet Project, 2002). The aim is to draw out the general principles on the best way to solve problems, be they problems of overnutrition or undernutrition, and irrespective of locality.

Table 6.1 Factors influencing effectiveness of intervention

Table 6.2 Key steps involved in planning, implementing and evaluating an intervention

A. Planning the program (PHN cycle steps 1–5) Identify the problem: epidemiological evidence I. Identify the determinants: (a) food supply (economic and physical access) (b) knowledge, attitudes and perceptions (c) skills (d)social and environmental factors II.Assess risks and benefits for possible or likely impact of the program: (a) likelihood of health risk or benefit (relative and absolute risk, population attributable risk, risk difference, number needed to treat) (b) vulnerable and target groups at greatest risk: (i) population and/or targeted approach (c) assess expected health benefit of intervention (change in risk estimates) (d) potential to succeed (e) nature and strength of evidence (f) other sources or causes of the same risk; interaction and overlap in population (g) impacts on other factors III. Assess needs and constraints in the population, including any subgroups: (a) structural, social and other determinants of behavior (b) barriers to change (c) environmental influences (d) educational and organizational (predisposing, enabling, reinforcing) factors (e) administrative and policy factors IV. Identify appropriate theoretical models upon which to base strategy (see Chapter 1, 5 and 8 for more details) V. Identify and appraise intervention options: (a) identify decision-making criteria: (i) effectiveness (ii) feasibility (iii) acceptability (iv) cost (b) consider types of interventions that may be appropriate: (i) policy (ii) programs (iii) infrastructure support (c) consider settings and approaches for options under (b): (i) define best practice within each setting (social marketing, point of sale, schools, worksites, food service, community, health sector, food supply) VI. Decide on the intervention portfolio VII. Choose indicators for evaluation VIII. Develop a budget for program IX. Establish partnerships and stakeholders: (a) engage stakeholders and put the problem in context (b) establish key players and who will own activity (c) consider those who may be adversely affected by program (companies, lobby groups) X. Project planning (develop written study protocol, built-in quality control and standards) B. Implementation of the program (PHN cycle step 6) I. Building the team, developing the protocol: (a) training and networking II. Implementation of the protocol: (a) piloting and feasibility, revision and refinement (b) monitoring and feedback, with sufficient flexibility to adapt project plans C. Evaluation (PHN cycle step 7) I. Formative evaluation II. Attainment of objectives III. Effects (e.g. behavior, risk factors, morbidity/mortality, structural or policy changes) IV. Costs V. Process VI. Other consequences VII. Feasibility for other subgroups, regions or countries (generalizability) |

PHN: public health nutrition.

Interventions may be broadly grouped into the following types:

- growth monitoring and promotion

- promotion of breast-feeding and appropriate complementary feeding

- communications of behavioral change

- supplementary feeding

- health-related services.

The distinction is whether the intervention includes supplementary feeding or not. The rest of this chapter will first consider interventions aimed at supplementing or changing food intake, and secondly interventions aimed at changing behavior without adding food or nutrients. The detail of identifying public health priorities, developing goals and targets and how to consider program options was covered in more detail in Chapter 1 and will not be repeated in this chapter. Table 6.2 modifies the public health nutrition (PHN) cycle to highlight the key steps involved in planning, implementing and evaluating an intervention. This is a modification of the precede–proceed model and was described in more detail in Chapter 1.

6.2 Interventions of supplementary feeding, foods or nutrients

A vast literature has been summarized by systematic reviews that explore the effects of changing diet on nutritional or health status, such as studies aimed at improving birth outcomes, childhood growth and micronutrient status. In addition, there are many reviews of the effects of changing diet on chronic disease risk factors, particularly blood pressure and blood lipids. The main findings of these reviews are summarized in the relevant chapters in this book. The aim of this chapter is to draw some conclusions and lessons about the process of undertaking these studies. Two types of question are asked: does it work in theory (efficacy), and does it work in practice (effectiveness)? In public health terms the interest is primarily in terms of effectiveness; often a program appears to work in theory, but when it comes to putting it into routine practice there are various practical (skills, resources, environment in general) factors that reduce its effectiveness. It is therefore important to be able to identify what these practical constraints are, and how to overcome them.

Some of the reasons why programs work in theory, but not in practice, are summarized in Box 6.1.

The principles of interventions using nutrients (aimed at assessing efficacy) in a controlled trial are exactly the same as those that apply to experiments in the laboratory: they must ensure blinding, randomization, and measures of compliance and loss to follow-up, and the sample size needs to be large enough to measure the expected and biologically relevant change (see Chapter 2).

There are many examples of randomized controlled trials of nutrients that can be shown to have improved the nutritional status of women and children. The impact on health is more difficult to assess, as there is often a complex interaction of factors that alter the demands for nutrients and therefore lead to apparently different effects of changing supply, at the same level of intake. It may also be difficult to measure intermediary markers of early change in functional state or health, such as cognitive performance or fetal health. Most obvious is the impact of infection, and perhaps for pregnant women, workload and or smoking. Previous malnutrition may have longer term effects on metabolic competence that alters the effect of current intake. During pregnancy it is critical to think about when to increase consumption: before conception, during the first, second or third trimester, or throughout pregnancy? The impact of supplementation may also differ depending on the age and parity of the woman, and the effects of changing the quantity of diet may be quite different depending on the overall quality of the diet. It may be that increased birth weight can be achieved not only with modest changes in energy intake, but also by improving the quality (increased nutrient density) of the diet.

- Problems with the reliability of supply, delivery and distribution of foods or nutrients

- Inadequacies in institutional capacity (training, supervision, monitoring, evaluation, community involvement)

- Poor targeting and control (leakage) over who receives nutrients

- Inadequate quantity, quality or density of foods, so that target audience does not receive enough

- Culturally unacceptable foods used

- Lack of understanding of beliefs and perceptions about intrahousehold food distribution practices

- Lack of counseling about needs for supplementary foods

- Failure to address other important causes of undernutrition

- Assess behavior (diet and activity levels, breast-feeding, etc.) before the intervention and identify sources of variation within the population: identify the problem and develop goals and targets (as outlined in Chapter 1) for the at-risk or target group

- Assess options as to the most effective way to achieve the target: when, what, how, when, cost

- Assess what support and infrastructure is required, whether it available, and if not how it will be developed

- Build in an evaluation strategy early on in the development of the intervention

Key points required in developing an individual intervention program are summarized in Box 6.2.

Evaluating effectiveness

Randomized double-blind controlled trials are not possible for food-based interventions and are very difficult for assessing effectiveness. In particular, there are ethical and practical issues about a control group that does not receive the intervention. Before and after studies may be the only options for assessing the impact of community-wide interventions.

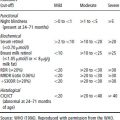

It is common to evaluate the effectiveness of fortification programs using an individual level of data collection, even though the intervention applies at a community level. For example, blood or urine samples may be taken from random samples of children both before and after fortified foods have been introduced into an area or country to assess mean changes in levels. It is not possible to link actual intake with levels because intake is not measured. It is assumed that any change in blood levels is due to changes in intake; this may be a reasonable assumption where areas with and without fortification are compared and are comparable in terms of background health status. It may be possible to randomize communities either to receive or not to receive fortified foods, but in general fortification is introduced to the whole community at once and it is therefore not possible to have a proper control group.

Factors influencing effectiveness

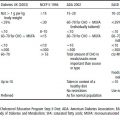

Lessons from anemia prevention trials can be used to illustrate the factors that influence effectiveness. Under carefully controlled circumstances (efficacy), giving more iron increases hemoglobin levels. However, effectiveness is affected by:

- lack of supplements on a reliable basis

- lack of information

- education and communication campaigns

- skills of health workers.

Factors that enhance the effectiveness of food-based interventions aimed at promoting growth include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree