Chapter Outline

CONCEPTUAL MODELS GUIDING THE PSYCHOSOCIAL CARE OF CHILDREN AND FAMILIES

PROFESSIONAL ROLES AND A TEAM APPROACH TO PSYCHOSOCIAL CARE

Presenting the Diagnosis and Plan for Treatment: Day One Talk

Parents’ Reactions to a Child’s Diagnosis

Children’s Reactions to Diagnosis

EXPECTABLE CHALLENGES DURING TREATMENT

Coping with Treatment and Adverse Effects

Maintaining Child and Family Routines

Transitions and Changes in Care

SPECIAL ISSUES THAT MAY ARISE DURING TREATMENT

The diagnosis and treatment of cancer represents a major challenge for the family and the individual child. For most families, coping with a child’s cancer will be the most stressful and difficult experience they will face. Although the majority of families will make an adequate adjustment, coping with the diagnosis and the subsequent challenges of treatment is a difficult and demanding process. In this chapter we will address the emotional and psychosocial needs of children and their families while the child receives a diagnosis of cancer and undergoes therapy, and describe some resources and interventions that may be useful. This chapter is intended primarily for oncologists, nurse practitioners, and other medical professionals who are seeking to understand and attend to the psychosocial needs of children with cancer. In each section we highlight the issues facing the child and family and suggest supportive strategies or interventions that may be helpful. A description of the psychosocial clinician’s role is included in certain sections so that oncology providers can better understand and collaborate with psychosocial clinicians, but readers looking for a detailed description of psychosocial assessment and treatment techniques will need to look beyond this chapter to more comprehensive treatments of the subject. Given the great variability in oncology diagnoses and treatments, as well as individual differences in children and families, we will focus on the issues that are most common in this population. Beginning with the crisis of diagnosis and proceeding chronologically through the treatment period to the end of therapy, we will address the issues that are expected to arise for most families.

Conceptual Models Guiding the Psychosocial Care of Children and Families

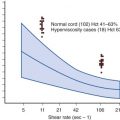

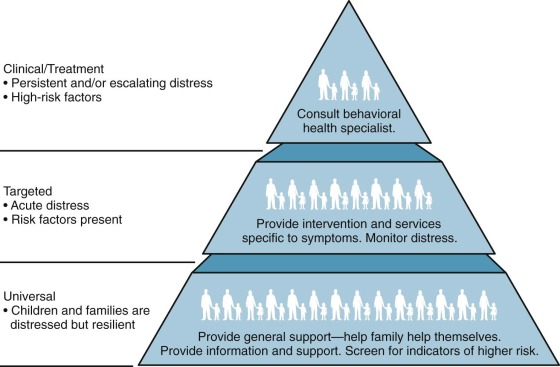

In approaching the topic of psychosocial care for the child and family, we have adopted a conceptual model developed by Anne Kazak that illustrates the different levels of need seen in families of children with cancer ( Fig. 73-1 ). In this model, adapted from the preventative mental health model, Kazak represents the distribution of families along the continuum of needs in the form of a pyramid, with the least acute needs at the bottom and the most acute needs at the top. The largest section of the pyramid at the bottom represents the majority of patients and families who have expected levels of distress but generally have adequate resources and may benefit from information and psychosocial support. Moving up the pyramid, the second largest group of families represented have more significant needs according to Kazak, either because of existing risk factors or the presence of more acute distress. Finally, at the top of the pyramid is the smallest group of families, whose level of distress is in the clinical range and for whom some significant behavioral or psychiatric intervention is required. This chapter focuses on describing the needs of the largest group of families with “universal” or expected needs and discussing the support strategies and interventions that can be helpful for them. In addition we address some of the special issues that are likely to be seen in the “targeted” group of families such as noncompliance or marital conflicts that are not typical but that the treatment team should be aware of and be prepared to address. In the less common situations in which patients or parents require significant mental health interventions, referrals to specialists are necessary; these situations will be discussed briefly at the end of this chapter.

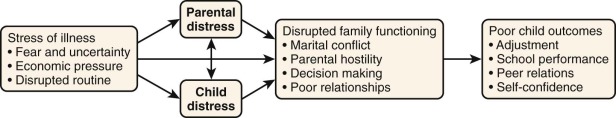

The ecological and developmental perspectives are also essential for understanding the experience of the child and family going through cancer therapy. Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) created the modern concept of the ecology of human development. In his model no one factor operates in isolation, and the biopsychosocial model is considered within a developmental context. At the core of the model, the child has genetic and environmental influences on emotions, cognition, and behavior. In addition the child’s own responses to the environment not only influence his or her emotions, thoughts, and behaviors but in turn influence the microenvironment. For example a child who responds to new situations with aggression or fear will elicit different responses from medical providers than will a child who responds with curiosity, and in that way the child shapes the environment to which he or she was initially reacting. At the next level of the model, the family system is a powerful factor that directly affects the child and shapes many of the child’s interactions with the environment. Family factors including family composition, parental emotional states, socioeconomic status, and other family stressors will influence the child’s experience of illness. For example parental depression might reduce the extent of nurturing and support provided to a child with cancer. Recommendations for family-centered care as the primary model of care delivery for children are supported by this aspect of the model ( Fig. 73-2 ).

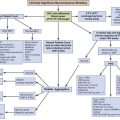

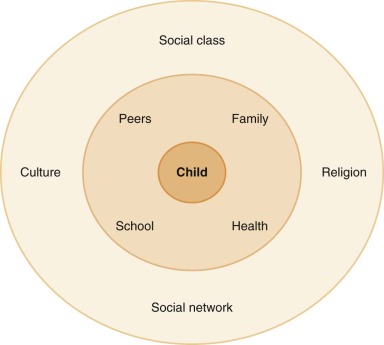

Finally, at the broadest level, racial, ethnic, community, and cultural factors can have an impact on the entire family/child system ( Fig. 73-3 ).

From a developmental perspective, children go through five recognizable stages of development from the newborn period until adulthood. These stages typically are thought of as infant, toddler, preschool, school age, and adolescence. Different developmental tasks are associated with each stage, and the needs for information, support, and care will vary in relation to the developmental stage of the child. A review of how to communicate with sick children during different developmental stages is provided by Rushforth. Pediatric health care providers are accustomed to tailoring their general approach to patients and families according to the child’s developmental stage and will draw on these skills and experience when working with children who have cancer. For example infants generally need a significant degree of parental soothing and physical contact, as do toddlers, yet toddlers need room for explanation and consistency in the environment. Preschool-aged children can understand simple information that can help reduce fears of the unknown. School-aged children need to have opportunities for peer interaction, as well as clear communication. Adolescents have a need for the development of autonomy and identity formation. When little room for individual choice is perceived by the adolescent, the drive for independence can lead to maladaptive coping, such as nonadherence to medications or refusals to come to the clinic or undergo medical procedures. Adolescents with cancer by necessity become more dependent upon their parents for physical and emotional needs and may have self-image issues related to weight loss or baldness, because during this developmental period perceptions of peer acceptance are important and sexuality develops as well. The specific needs of the adolescent patient are discussed in a separate section.

Professional Roles and a Team Approach to Psychosocial Care

No single individual is able to provide for all the psychosocial needs of the child and family undergoing cancer therapy. In many pediatric oncology settings a team approach is used, with the team composed of both medical and psychosocial care providers. The composition of the medical members of the team vary from setting to setting, but the team generally includes an attending oncologist, a surgeon, and a radiation oncologist (if these treatment modalities are indicated), as well as other oncology care providers such as an oncology fellow, a nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant, and an oncology nurse. Psychosocial members of the team may include a resource specialist, social worker, psychologist, child life specialist, or psychiatrist. Variation in the professions included in the psychosocial support team in a particular treatment setting generally has more to do with local culture and tradition than with the specific training or skills of a particular profession. Although each psychosocial discipline has its particular focus or specialized skill set (e.g., prescriptive authority or psychological testing) in working with children who have cancer and their families, considerable overlap between their roles is likely.

Psychosocial professionals have several important roles on the care team. The primary role may be as a consultant to other members of the team, including the patient and the family. Because all team members will be interacting and providing some level of information and support, they will need to attend to psychosocial concerns, and developing a consistent approach to support of the family is essential. As a consultant, the psychosocial team members should conduct a preliminary assessment of the child and family to understand their history, preferred ways of coping, important supports, and potential sources of vulnerability. Using this knowledge of the family, the psychosocial care provider may be able to help the other team members understand the family’s individual needs and consider best approaches for supporting them. Similarly when the patient or family has questions and concerns that are not resolved in the course of routine care, the psychosocial care provider may help them work on solving the issue and think about how to help them raise their concerns with the medical team. The emphasis of these consultations is on improving communication between the family and the medical team, and in most instances these consultations focus on clarifying and correcting misunderstanding rather than resolving conflicts. In cases in which the family is very reluctant to address a concern with the medical team, or when a more significant conflict exists with the medical team, the psychosocial team member may be asked to play a more formal consultant role. Psychosocial team members also fulfill the role of direct service providers to patients and families, providing individual or family meetings to offer support to the parents, patient, or family, as well as education and preparation for surgery and other medical procedures. Support groups run by psychosocial and/or nursing staff in the inpatient or outpatient setting may be very helpful for meeting families’ educational and emotional needs. Finally, the psychosocial provider’s role often includes consultation and liaison with outside agencies and community resources. This aspect may include assisting families in accessing financial and insurance resources, contacting schools, tutors, and other child care agencies, and helping identify additional support services in the community, including referrals for psychotherapy when appropriate.

Crisis of a Cancer Diagnosis

The cancer diagnosis and the events leading up to it are typically frightening, complex, and unfamiliar. The diagnosis period, which can be thought of as beginning when the child first comes to medical attention until a clear diagnosis and treatment plan are made, is foremost a period of uncertainty. At some point in this period, parents are told cancer is possible or even likely, but it may take time before a definitive diagnosis is made. During this period their child’s symptoms may persist and the child often must face painful diagnostic tests and procedures.

Until their child is diagnosed, most families have never thought about childhood cancer and don’t know anyone who has had to face it. Whereas families facing common stressful life events can be guided by their prior experiences and the experience of their friends and family, the cancer diagnosis pushes them beyond the realm of ordinary experience. Not surprisingly parents are typically overwhelmed emotionally and cognitively while they try to understand their child’s illness. In addition parents may describe feelings of unreality, “like this is not really real.” Children’s immediate reactions to illness depend largely on their age, their symptoms, and the medical procedures they have had to undergo. Except in cases of older adolescents, it is most often the parents who are most anxious to learn the diagnosis and are the first ones to be informed of the diagnosis of cancer.

Presenting the Diagnosis and Plan for Treatment: Day One Talk

The diagnostic period comes to a close when the treatment team has made a clear diagnosis of the child’s cancer and communicates this diagnosis and related treatment plan to the patient and family. Often referred to as the “day one talk,” this conversation with the family usually takes place in the form of a treatment conference between the family and several members of the care team, including physicians, nurses, and psychosocial care providers. The day one talk is a comprehensive discussion and usually the first to address the child’s prognosis and specific treatment recommendations. For many families this meeting is a pivotal event in their lives, marking the real beginning of their child’s cancer. Throughout the diagnostic phase most families maintain hope that the child does not in fact have cancer, so the day one talk is similar to other situations in which a physician must communicate bad news to the family. The literature on communicating bad news about a child’s health may be relevant, and recommendations from these noncancer settings may be instructive. Box 73-1 provides a summary of essential points for communicating the diagnosis.

Structure—Organization

- •

Establish an initial plan for communication.

- •

Communicate in a private and comfortable space where interruptions will be minimized.

- •

Communicate with the parents, child, and other family members, if desired. Nursing staff and psychosocial workers should also be included whenever possible.

- •

Hold a separate session with the child if he or she is not present for the initial communication.

Content—Information to Discuss

- •

Solicit questions from the parents and child, especially regarding their understanding of the present illness.

- •

Share information about the diagnosis, treatment, and the plan for cure and/or goals of treatment.

- •

Share information on lifestyle and psychosocial issues, particularly surrounding causation (e.g., the cancer is neither the child’s nor family’s fault).

Process—Process of Communication

- •

Communicate immediately at diagnosis and follow-up later.

- •

Communicate at a pace the family can follow, allowing the child’s or family’s emotional reaction to guide the flow of the conversation.

- •

Communicate in ways that are sensitive to cultural differences (e.g., for families who are not native English speakers, arrangements should be made for an interpreter).

- •

Encourage the entire family to talk together.

Although the medical details discussed will vary from one family to the next, challenges in communicating diagnostic, prognostic, and treatment information are consistent across families and can be considered and planned for. Planning is essential for a successful meeting with the family, and although there may be pressure from family or medical staff to have the conversation as soon as possible, some minimal amount of scheduling and organization will be required. A written protocol for communicating the diagnosis has been recommended, with the expectation that this protocol will be tailored to meet the needs of the patient and family. Conducting the meeting in a private space while all participants are free from interruptions is very important, as is scheduling the meeting so that the important members of the family and care team can attend. Because families typically find the day one talk overwhelming and may not remember many of the details discussed, some practitioners recommend providing written material or making a tape recording of the meeting for the parents to review subsequently. Reassuring families that they are not expected to remember all of the details discussed can reduce their sense of information overload, as will making explicit the critical pieces of information they are being asked to focus on.

In addition to the oncologists directly caring for the patient, the day one talk should include nurses and psychosocial caregivers whenever possible. The organization and roles of the medical center staff are often confusing to families, and taking time to introduce the different members of the team and describe their roles is essential. Both parents should attend, and they should be offered the opportunity to include other family members involved in the care of the child. Whether to include the child in all or part of this session or to arrange for a separate session for the child will depend largely on the age of the child and the parents’ preference. Although a subsequent meeting with a smaller group consisting of parents and one or two medical professionals may be more appropriate for younger children, including adolescents in the day one talk can help them develop trust in the medical team and invest in their own care.

The principal goal of the meeting is to provide the family with an overview of the child’s diagnosis, the treatment recommendations, and the prognosis. It is important to directly elicit questions the patient or family may have and to provide sufficient time to discuss their concerns. Mack and Grier emphasize the opportunity to address the family’s questions about what may have caused the child’s cancer and particularly to correct misconceptions that may lead to a sense of blame or responsibility for the cancer. Communicating prognostic information to the family is critical because it is likely to have an impact on their understanding of the treatment recommendations, but delivering this information can be difficult, especially when the prognosis is guarded or poor. How much to rely on a numeric presentation of this information is a question that frequently arises, and some evidence indicates that patients may misunderstand the information if it is not carefully explained. Numeric information about risk, such as 5-year survival rates, should not be avoided altogether because many families want this information, but care should be taken to ensure that parents receive the information in the way they find most useful and that they understand the information that is provided. Recommendations for treatment should be presented, beginning with a general overview of the modalities used and the timing and setting for treatments. The introduction of consent forms and discussion of known and likely adverse effects (short term and long term) should follow after the family understands the general outline of the treatment.

If a separate session for the child is held, the same general information about diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plan should be covered. The information will need to be tailored to the developmental level and the particular concerns of the patient, such as the ability to return home and to school, to see friends, and to participate in sports or other activities. Children should be told about specific expectable adverse effects such as hair loss, with an emphasis on concrete ways in which their appearance or activities may be affected. Older children and adolescents may be able to engage directly with the medical providers, but younger children may be more comfortable talking with their parents, who can elicit their questions and reinforce what medical providers communicate to the child directly. Most professionals will emphasize the importance of the children knowing the name of their disease and that it is cancer. Parents may initially shy away from this direct approach and particular words like “cancer,” and they may need some preparation for how to talk with their child and what words to use. Understandably many parents feel protective toward their children and may wish to avoid using the words “cancer” or “leukemia.” It is important to help parents understand that honesty, even about potentially frightening information, can decrease anxiety and be supportive for children in the long term because they can grow to trust that adults are not withholding information and that they need not fear unpleasant surprises. Similarly it is important to explain that the word “cancer” is commonly used with pediatric patients and that it is important for children not to feel that their condition is so frightening it cannot be named or spoken about. It can be helpful to share with parents that the climate of open communication with young patients comes from lessons learned in past treatment eras when communication was not open, which contributed to children’s anxiety and fear about their disease. With this sort of preparation, most parents can begin to feel comfortable with open communication with the child. Parents from different cultural backgrounds, or those who are unused to open discussions of illness, may not easily accept this openness and naming of the disease, and some careful negotiation and compromise may be required to reach an agreement of what words to use and topics to discuss with the patient. Over time families may become more comfortable being open with the patient themselves, while they meet other families and children whom they see are comfortable with this type of open discussion. In an elegant description of the day one talk in pediatric oncology, Mack and Grier highlight the importance of forming an alliance between the family and the medical provider and the ways in which this alliance can affect adjustment to the diagnosis. In particular they emphasize the importance of listening closely, making an emotional connection with the family, and acknowledging the overwhelming impact of the diagnosis on every aspect of the family’s life. Although they provide some very specific guidelines for the information that should be discussed, they conclude, “…listening and the openness of silence may be more important than the words themselves.”

Parents’ Reactions to a Child’s Diagnosis

Many factors can contribute to the overwhelming nature of the cancer diagnosis. The word “cancer” continues to have a significant social stigma, as well as personal connotations. For many parents, their personal experiences with cancer may be limited to relatives who were diagnosed later in life and may not have survived long after diagnosis. Although it can be helpful to learn about these personal associations with cancer, it is very important to clearly correct parents’ explicit or implicit assumptions as they apply to their child’s illness. Families who have lost family members to cancer may need very explicit explanations that a parent’s or grandparent’s experience with prostate or lung cancer may have little in common with a child’s diagnosis of cancer.

In the context of a new diagnosis, most parents will experience many intense emotional reactions and may even report psychiatric symptoms of acute stress. They are typically frightened and anxious about their child’s prognosis and distraught at the thought of their child’s physical suffering. If many days or weeks elapse between the child’s initial symptoms and the diagnosis, parents may feel angry at medical providers, whom they believe “missed the diagnosis” or did not listen to them or to their child. Parents’ belief that there was a delay in diagnosis may also contribute to feeling angry at themselves. Parents are ordinarily active agents in shaping every aspect of their child’s care and well-being and may feel quite dismayed at how helpless they feel to protect their ill child. This sense of responsibility may lead many parents to feel responsible for their child’s situation, perhaps blaming themselves for not bringing the child to medical attention earlier or for not understanding the significance of a child’s initial symptoms. In some cases this sense of responsibility and the need to understand the cause of the child’s illness may make parents (or other family members) wonder if they themselves are responsible for the cancer. Examples of these thoughts, many of which are not entirely rational, might be wondering if allowing their child to use certain electrical devices, or bringing some kind of contamination into the home from a work site, may have contributed to the cancer. For families coping with neurofibromatosis, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, or other genetic predispositions, a child’s diagnosis of cancer may weigh more heavily on parents and leave them more vulnerable to psychosocial distress. The psychosocial care provider can play a crucial role in helping families reframe these difficulties, which will allow them to cope more effectively. In addition encouraging families to pursue a consultation with a genetics counselor can be an important intervention in helping families gain increased knowledge about the genetic predisposition to cancer and develop strategies to decrease stigma and fear and increase appropriate management of risk. Listening to the family in crisis and providing reassurance can be the most useful responses for all members of the care team. Normalizing parents’ reactions by letting them know that parents almost universally feel overwhelmed and that intense emotional reactions are normal responses to their child’s illness can help reassure them that they are not “going crazy” and they won’t be judged for their reactions by the care team. One reason parents feel overwhelmed is their awareness that they are facing a more complicated, frightening, and demanding challenge than they may have ever faced before. Although it is helpful to acknowledge the feeling of facing this seemingly overwhelming challenge, it is also useful to let parents know that families do cope well, and with some assistance and support, there is every reason to believe their family will cope successfully, even though that may be difficult to imagine at the beginning of treatment.

During the crisis of diagnosis, many families will benefit from concrete structuring from the care team. Parents often need to be encouraged to focus on their own self-care and may need encouragement to mobilize their social supports to meet their acute needs, such as arranging extended time off from work or asking friends and extended family to help with other tasks. Many parents can benefit from some active problem solving, with staff helping them to identify needs, generate possible solutions, and then select and implement a potential solution. Social workers and resource specialists on the care team may be helpful in identifying sources of practical support (e.g., transportation, meals, and lodging), sorting through insurance issues, and helping solve problems with regard to meeting the needs of the patient and family.

Occasionally some parents experience such a strong need to act in the face of their child’s illness that they make decisions that can be premature or even impulsive. For example some parents have quit their jobs, mortgaged their homes, or moved their residence even before knowing the details of their child’s treatment and taking time to consider these major life decisions. Although parents need to decide for themselves how their family will adjust and cope with the demands of the child’s illness and treatment, it is appropriate for members of the care team to caution against making impulsive decisions and support them in making short-term plans for managing the health crisis that can be revised as circumstances change or new information becomes available.

During the crisis period parents can experience a wide range of intense emotional reactions. In most cases parents’ reactions can be managed with education and support from the care team. Specialized services from a psychosocial care provider, usually a psychologist or social worker, can be particularly useful in helping parents identify and begin to cope with their emotional reactions. Many of these reactions will be of short duration because parents often report feeling less overwhelmed after they have heard a definitive diagnosis and can focus on the demands of a treatment plan. Research has demonstrated that the initial psychological distress experienced by mothers at the time of diagnosis tends to steadily improve as long as 6 months after the diagnosis. In rare cases parents may have emotional reactions that are more enduring or problematic, which may require more targeted intervention during the crisis period. Situations involving confusion about the child’s diagnosis or requiring a prolonged diagnostic evaluation period are more stressful for parents and may be more likely to cause significant distress. Similarly parents who are managing other significant stressors such as having a parent or other family member with medical needs and parents with preexisting psychological problems will be more likely to have symptoms that interfere with their ability to function ( Table 73-1 ). Examples of these problematic reactions might include manifesting signs of clinical depression or anxiety, not being able to care for themselves adequately (i.e., not sleeping or eating), or being so frustrated and angry that they cannot consistently collaborate with medical providers. In these situations in which parents’ reactions will have a negative impact on the child and have the potential to interfere with the treatment process, it is important to address the situation directly with the parents and make appropriate referrals for intervention.

| Family Factors | Disease Factors | Environment/Resource Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Single-parent families | Unclear diagnosis(es) | Financial problems (e.g., job loss or debts) |

| Preexisting chronic or mental health | Poor prognosis | Isolation (e.g., lack of family and/or problems with peer support) |

| Concurrent illness or injury in family (e.g., parent or sibling illness) | Prolonged or intense treatment(s) (e.g., bone marrow transplant) | Language differences (e.g., foreign national or immigrant) |

| Marital problems (e.g., separation and/or divorce) | Disfiguring disease or treatment(s) (e.g., amputation) | Transportation (e.g., no car to get to the hospital) |

| Family problems (e.g., emotional or learning difficulties) | Disease status (e.g., relapse or recurrence) | Minimal or no health insurance |

| Recent stressful life events (e.g., job and/or school problems, a move, or relocation) |

Interventions for parents experiencing these problematic reactions may require more intensive services from some members of the care team, as well as consultation with and referral to other individuals. The underlying problems may predate the child’s cancer, but the focus of intervention during the crisis of diagnosis may appropriately be alleviation of symptoms. Parents showing signs of severe distress should be evaluated by an appropriate psychosocial team member or be referred to a mental health provider who can assess their psychological status and refer them for any urgent intervention they may need. In addition to supportive therapy and the problem-solving approaches previously described, psychopharmacologic intervention may be particularly helpful for parents who have severe anxiety or depressive reactions, severe sleep disturbance, or a preexisting psychopathologic diagnosis. Pastoral counseling may be useful for parents whose faith is an important source of support and for those experiencing a “crisis of faith” as they struggle to make meaning of their child’s illness.

Children’s Reactions to Diagnosis

Children will react to their diagnosis and initial treatment on the basis of their developmental level, their own individual temperament and past experiences, and to a large degree on how their parents cope with the new diagnosis and treatment. Typically the infant, toddler, and especially the preschooler will be more concerned about changes in routine and the normal home environment, separation from family, especially the primary caregiver, and bodily intrusion through physical examinations and medical procedures for diagnostic or treatment purposes. Strange environments will disrupt normal awake/sleep patterns, and sleep deprivation can reduce the child’s normal self-regulation effectiveness. For example infants who had been able to sleep through the night at home might have constant awakenings. Separation from the primary caregiver(s) then becomes an even larger issue if the parent is not present during the night or during bodily intrusion episodes to help comfort the child. Clearly this need for the parents suggests that, when possible, it is better for parents to create “shifts” to be with the child as much as possible, day and night. Such parental support also means that the issue of support for parents, both emotionally and in practical ways, needs to be addressed. Stressed parents who cope poorly will not be able to help their child self-soothe well.

One issue that the medical team can address is the manner in which examinations and procedures are carried out. For example Chen and colleagues found that children had memories of stressful and painful procedures that affected their experience and behaviors during subsequent procedures. Asking the parent to leave the room while a team of doctors and nurses in white coats enter the child’s room to carry out examinations is more likely to help create an uncooperative child who will become conditioned to be anxious around anyone with a white coat. Having one member of the team develop a relationship with the child, from toddlerhood through adolescence, will be helpful in establishing the child’s trust of the nonfamily “team.” Establishing a system for families in the hospital that sets clear guidelines for providers as they enter a child’s room can prevent significant distress. For example psychosocial providers or child life specialists can create a sign for the door that reminds providers to introduce themselves when they enter the room, let the child know up front what is going to be required of them, and hold medical discussion outside the room when appropriate. Respecting such requests fosters rapport, reiterates the message that the child and family are part of the team, and promotes the sense of being “heard” by the medical team.

For the very young child, procedures that can be performed competently and quickly while distracters are present (e.g., iPad apps, bubbles, party blowers, cartoons, and stories) can reduce fear of future procedures and help the child develop a sense of control and cooperation. The use of positive reinforcement is helpful in an effort to pair “scary” novel and intrusive experiences with positive, pleasurable experiences. The use of behavioral strategies (e.g., breathing, relaxation, imagery, and behavioral charts) can provide parents with ways to support their child in these novel and intrusive situations and help the child develop a sense of security and mastery, and they give parents the opportunity to feel successful in the context of challenging medical demands. Additionally it may be useful to encourage the family to bring in a “transitional object” for their child (e.g., a favorite blanket or stuffed animal) to bring the familiarity of “home” into the hospital.

School-aged children will be interested in concrete answers to their questions about hospitalization, expectations with regard to medical examinations, and specifics about what to expect in unfamiliar situations. Encouraging parents to answer questions directly, even when the topics may be uncomfortable, will foster open communication and minimize the chance that the child will create “answers” based on faulty assumptions that can be anxiety provoking. Parents should be reminded that this is not a one-time discussion and that providing their child with information, even upsetting information, can decrease uncertainty about the illness and potentially improve psychological functioning.

While children develop an increased understanding of their illness, they may ask, “Am I going to die?” Psychosocial providers can help guide parents in providing answers to this question based on a child’s age and diagnosis. It is important for parents to acknowledge the severity of the disease while highlighting the fact that the medical team has a treatment for the illness. Answers to this question will vary based on a child’s medical condition, particularly in the case of relapse. Exploring a child’s thoughts and fears around illness and death can be helpful; however, providing reassurance that he or she will be well taken care of and not left alone and that his or her symptoms will be treated is critical.

Adolescents are likely to want to know more information about their illness and treatment. Simple responses to questions often will not satisfy them, and parents will need to understand that adolescents may potentially turn to alternative sources beyond their parents for important information. A child or adolescent who has formed a relationship with a member of the treating team can ask questions of that team member that might seem difficult to ask parents. Some adolescents feel a need to “protect” their parents from more stress by not acknowledging to their parents their own fears, anger, and worries. Encouraging adolescents to talk about what they have learned from their medical providers, the Internet, and their peers will help eliminate misinformation and confusion while empowering adolescents to seek information in their own way. Developing a sense of mastery over the medical information can lead to a feeling of control and confidence that can be helpful for teenagers.

Finally, children of all ages often regress when they are scared, and parents need to know that changes in the child’s behavior are not unusual. Psychosocial providers can normalize behavioral reactions for parents and subsequently minimize the distress associated with particular behaviors. For instance a preschooler who has just been toilet trained may begin having accidents, and it is imperative that parents recognize that this behavior is a normal response to a stressor and that they should not focus too heavily on that behavior during a time of crisis. The following guidelines are related to children’s reactions to diagnosis and treatment:

- •

Many parents need help talking with their child, who is often scared and needs some explanation and education along with his or her parents.

- •

A variety of disciplines, such as child life, nursing, social work, and psychology, can all be helpful to parents, siblings, and pediatric patients. Interventions relating to preparation for medical procedures, supportive work with parents and other family members, and psychoeducation are important. Connections with other children and families who are having similar experiences can be helpful.

- •

Keys to getting through diagnostic procedures are good preparation and good pharmacologic and psychological pain and anxiety management.

Education and Information about Treatment

Most treatment regimens put an enormous information burden on the family. Children are often treated with several modalities (such as surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy) and may receive a large number of medications, as well as a variety of blood tests and other diagnostic procedures. Although adolescents may be active in their own care to some extent, parents are responsible for understanding and managing their child’s treatment, especially during outpatient phases of treatment when parents will need to work with home care agencies, administer treatments themselves, and monitor their child’s health. To meet these demands, parents require detailed information about their child’s treatment regimen and reactions that can be expected. Most of this detailed information will be provided by nursing and medical care providers. Patients and families are generally quite resilient and successfully accommodate even the most demanding treatment regimens, but initial apprehension about being able to understand and implement these regimens is common. Staff may need to present information several times and reinforce verbal exchanges with written materials. While remaining optimistic and encouraging families to develop competence, it is also important for providers to recognize the complexity of what they are asking of families and the burden it imposes. Normalizing the common feelings of anxiety and “information overload” while focusing on problem solving in the face of new demands is an important role for the psychosocial clinician. Talking with other families who are undergoing similar treatment can be particularly helpful, and many centers offer education and support groups for new patients and families. In addition a wide variety of books useful to parents and helpful for patients and siblings may be available from hospitals, libraries, and booksellers.

Among older children and adolescents, interest in or openness to learning more about their illness and treatment can be highly variable. Because they have more developed cognitive and language abilities than younger children, older children can ask more questions and understand more about their treatment, and like parents, they may receive educational information from nursing staff as previously described. To the extent of their capabilities, adolescents should be encouraged to participate in their own treatment by learning about their medications and schedule, helping with simple self-care activities such as routine care for a central venous line (CVL), and learning the best ways for them to cope with adverse effects or medical procedures. In some cases adolescents may not be interested in some of this information or may feel disinclined to assume even basic self-care responsibilities. It is not uncommon for adolescents to feel overwhelmed by information about their disease, particularly given the typical developmental milestones they are attempting to navigate. Feelings of distress associated with a loss of autonomy may lead adolescent patients to become more withdrawn. It can be helpful to empathize with adolescents’ plight of feeling “pushed around” while actively working with them to develop adaptive coping strategies that may lessen their feelings of helplessness. It is often important to point out that although many aspects of the situation cannot be changed (i.e., you have cancer, you need treatment, and the treatment will cause you to miss school), some aspects can be changed (e.g., you can maintain ties with friends through texting, social media, or visits, you can keep up with school work, and you can plan a party or an outing to celebrate an upcoming treatment milestone). It can be overwhelming for parents to include adolescents in difficult conversations about their illness and treatment, but adopting a model of shared decision making with adolescent patients in the early stages of treatment can empower patients, improve comprehension and understanding of the treatment plan and toxicities, and enhance communication among parents, patients, and providers.

The Internet

In addition to obtaining medical information from medical teams, outside consultations, and family and friends, parents also gather information from the Internet. The ability to access information quickly and conveniently is appealing to parents who can feel overwhelmed during medical discussions. Given that it is common for patients and parents to use the Internet to gain knowledge about their disease and treatment, it is crucial that medical providers help families identify appropriate websites where they can access accurate information. In particular providers should consider providing parents with a list of recommended websites. These websites may include local resources affiliated with the treating institution, disease-specific resources, and general pediatric cancer sites facilitated by reputable organizations such as the Children’s Oncology Group, Pediatric Cancer Research Foundation, National Cancer Institute, and the American Childhood Cancer Organization (e.g., www.curesearch.org , www.pcrf-kids.org , www.cancer.gov , and www.acco.org ). The National Cancer Institute website offers educational materials in both English and Spanish. Ensuring accuracy of information is important not only for the parents’ understanding but also for that of adolescent patients who frequently access the Internet. Using a search engine to research a cancer diagnosis and treatment does not always lead to relevant content. In addition the readability of websites is highly variable, and the information provided on some websites may be difficult for some parents and patients to understand, potentially leading to additional confusion at an already challenging time. Potential exposure to difficult material (e.g., prognosis, individual narratives, and grief) without the immediate support of the medical team can be a particular concern. Having a discussion with families about the dangers of exploring too broadly on the Internet early in the diagnosis and treatment period is important so they can avoid exposure to potentially upsetting information.

Despite the potential challenges associated with gathering information via the Internet, this avenue provides some clear advantages for parents and patients, and research is burgeoning in this area to best meet the needs of the families. Open patient-physician communication with regard to gathering information, asking questions, and researching treatment options and plans can help minimize confusion or distress based on misinformation obtained via the Internet. This approach represents a movement away from the more paternalistic approach, and medical providers can encourage families to conduct their own research and come back with questions or concerns.

Adjusting to Treatment

While the child and family come to understand the diagnosis and treatment plan, their focus begins to shift from managing uncertainty to coping with the demands of treatment. Although parents in particular will continue to worry about their child’s prognosis for years to come, the day-to-day demands of treatment along with the other demands of work and family life become increasingly salient. Families often experience a subjective sense of relief associated with a reduction in uncertainty, but they may also have an increased sense of burden. During the crisis of a new diagnosis, parents usually take time off from work and temporarily set aside many practical concerns. With the initiation of treatment, parents and children typically need to return to their regular roles and responsibilities while also taking on the new responsibilities associated with treatment. During this period of adjusting to treatment, families often benefit from continued psychosocial assessment, education, and support. In actual practice, encounters with the patient and family will blend these three objectives, especially at the initiation of treatment, but they are presented separately here for clarity of presentation.

Psychosocial Assessment of the Patient and Family

Experienced psychosocial care providers generally have a way of conducting an assessment that is comfortable for them and generates the relevant information. For illustrative purposes, a general approach to the assessment interview will be outlined here and in Box 73-2 . The process of the interview should include time for the family members to speak about their concerns, but the provider will need to actively direct the conversation to ensure that the necessary topics are covered. In an interview with both parents if possible, the provider may begin by asking about the general family history and then focus on the patient’s premorbid functioning, a developmental history, and the relevant history of any other children. Details of the patient’s functioning at school and relationships with peers and siblings should be solicited, as well as prior experience with stressful situations and any behavioral, developmental, or emotional concerns prior to the cancer diagnosis. In learning more about the parents, it is useful to know the basic outline of their families of origin, their current work or family roles, and any religious and cultural traditions that may affect their ability to cope with the illness. It is important to know if the family has had to cope with significant stressors in the past and if any other significant problems exist in the family at present. If the parents are divorced or not married, understanding this history, as well as the practical and legal aspects of any custody arrangements, is critical. Understanding the family’s practical and social resources is also an important component of the assessment.

Structure of Interview

- •

One to three intake meetings with patients and parents, conducted by a mental health professional.

- •

Meetings held in a relaxed, nonthreatening setting.

- •

Written summary of assessment to be shared with the treatment team.

Assessment Content

Illness Context

- •

Initial presentation of the illness.

- •

Diagnosis, prognosis, and anticipated treatment.

- •

Previous child and family experiences with physical health problems and behavioral problems.

- •

Family’s coping, especially cohesiveness, communication style, and ways of resolving conflicts.

Child Patient

- •

History

- •

Developmental—milestones, temperament, delays.

- •

Medical—previous diagnoses and responses to medical care.

- •

Behavioral—energy level, moods, and sleeping/eating habits before and after the illness.

- •

School and Social—relationships with parents, siblings, and peers, educational history, and functioning in school.

- •

- •

Response to diagnosis and coping style.

Parent and Family

- •

Background and History.

- •

Basic structure and involvement of extended family.

- •

Sources of social support.

- •

Relationships, sources of conflicts, and cohesion.

- •

Physical and mental health.

- •

Sibling relationships.

- •

Parent education and employment.

- •

Religious beliefs and cultural traditions.

- •

Parenting styles.

- •

- •

Initial Response to the Diagnosis

- •

Knowledge and understanding of diagnosis.

- •

Level of distress—emotional and physical symptoms.

- •

Strength and vulnerabilities during the crisis.

- •

Coping styles and experienced need for support.

- •

Expectations and sources of stress and anxiety.

- •

Resources

- •

Housing.

- •

Names and ages of family members living at home (e.g., siblings and grandparents).

- •

Available support for work, neighborhood, and school.

- •

Financial status.

- •

Health insurance.

- •

Involvement within the community and social supports.

- •

Travel time and transportation to treatment center.

- •

Resources available during the child’s ongoing medical treatment.

The assessment of the pediatric patient will vary significantly depending on the child’s age and medical status. With an infant or toddler, the child will be seen along with the parent, and the goals may be to observe the parent-child interaction, appreciate the child’s temperament and reaction to the medical setting, and establish the psychosocial provider as a friendly and nonthreatening presence. With older children the goals will also include directly assessing their reaction to their illness as they are able to express it verbally or in play. Because children typically have met many health care providers in the hospital or clinic, it is important for the provider to begin by introducing himself or herself, describing the purpose of the meeting, and reassuring the child that there will be no medical examination or use of needles during the meeting. With most children, even into adolescence, the assessment can be greatly facilitated by including action, such as unstructured play, a walk in the hospital, a craft, or a game.

With preschool and school-aged children, familiar activities such as drawing or symbolic play with dolls or puppets can serve the dual purpose of engaging them and providing an expressive medium through which they can relate their concerns. When children are engaged in this type of play, the provider can assess them by observing or participating in the play, as well as by asking them questions about their illness, their medical care, and how they are coping (e.g., “What has been the hardest part about being a patient?”). For older children, questions about life before cancer including friends, hobbies, and school activities can be a good starting place before asking about their illness and how they are coping with their medical care. It is important to ask older children directly about any worries, anxiety, and symptoms of depression or hopelessness, as well as how the adults involved in their care can best help and support them.

Adolescents may have very personal concerns about how their illness will affect them, such as by causing them to miss an upcoming social event or interfering with a particular friendship or a dating or romantic interest; such concerns may not be immediately apparent to the parents or the medical team. Asking explicitly about what they anticipate will be difficult about their treatment plan is an important part of the assessment, as is inquiring about ways they believe they will deal with the challenges of treatment. Family systems often shift in response to a child’s illness, and it can be important to understand the changes adolescents may have experienced and how those changes may be affecting them, especially because adolescents in treatment may become more dependent on their parents and spend more time with them than they normally would. Because adolescents often believe that the patient role limits their privacy, agreeing ahead of time with parents and adolescents about what information from the adolescent interview will need to be discussed with parents and what information everyone agrees can be kept confidential will be important.

After concluding the interview with the patient, it is important to give feedback to the parents about what was discussed, the child’s main concerns, and generally how the patient is coping with the illness and the demands of treatment. If the psychosocial care provider has specific recommendations for further assessment or intervention, they should be explained to the parent and patient. For illustrative purposes this description has emphasized the information that should be gathered in the assessment, but the process of the interview should accommodate both the goal of assessment and the goals of education and support.

Support for Parents and Families during Treatment

Families may require very different levels of psychosocial support during treatment, and even within a single family, needs will vary over time. Ideally psychosocial support can be offered to patients and families in a flexible way that can be tailored to their individual needs. This flexible approach requires some ongoing assessment and communication with families about their coping and adjustment, as well as the ability to quickly adjust the level of services offered to each family. Families typically require more intensive involvement from the psychosocial care provider during the diagnostic period and the beginning of treatment, as previously described. Some families may continue to have high levels of emotional distress or ongoing problems adjusting to treatment ( Table 73-1 ) and will require continued regular meetings with a psychosocial provider, but many families will not have this need. For families who are adjusting adequately to the routine of treatment, their need for psychosocial care often decreases. For these families the psychosocial care provider may briefly check in with patients and parents in the context of their regular medical care. These brief visits may be useful for assessing their adjustment and reinforcing previously offered suggestions and interventions. The psychosocial team may also offer information about educational and support groups, which can be particularly helpful for parents adjusting to treatment.

With any decrease in intensity of direct psychosocial involvement, care should be taken to ensure that patients and families do not feel abandoned by the psychosocial care provider. In most clinical settings a team model is used in which medical providers and psychosocial clinicians are in frequent communication so parents can be assured that when important medical changes occur that have potential psychological implications, psychosocial care providers will be informed and will intervene as appropriate. It is important to review with parents the expected challenges that may arise during the course of treatment (described in the next section) and encourage them to contact the psychosocial care provider if they need assistance with these or other issues that arise.

If some adjustment problems arise during the course of treatment, such as problems at school or difficulties with discipline, the psychosocial care provider should offer symptom-focused interventions such as educational support, behavioral intervention, or other counseling. Typically this intervention may involve a small number of sessions delivered as part of the patient’s regular medical visits or a referral for short-term therapy within the treating institution or in the community. While the presenting issue is resolved, children and families will typically return to their previous level of adjustment, and the intervention can be tapered off and discontinued.

Some families will experience brief periods of intense emotional distress related to the stress of cancer treatment. These episodes may occur when they are facing painful or unpleasant therapies or when treatment complications arise. Intervention for moderate to severe distress could include an increase in the intensity of routine psychosocial support services, consultation with additional mental health providers to provide crisis intervention, psychiatric assessment, and use of psychopharmacology for patients or other family members. In the outpatient setting, referral to outpatient providers in the community will also be important.

Some children and families will require a more intensive level of psychosocial care consistently throughout treatment. In most cases these families have high emotional distress, multiple stressors, or limited resources, which can often be recognized during the psychosocial assessment (see the previous section). For most of these children and families, regular ongoing psychosocial services will need to be provided for much or all of the treatment period. In these cases the psychosocial care provider should consider several types of intervention, such as play therapy, cognitive-behavioral treatment, and parent guidance. Referral to other specialists, either within the treating medical center or in the community, is useful when specialized services are needed (e.g., psychopharmacology) or the child or family needs more intensive treatment than can be accommodated within the oncology clinic. Referral for outside services such as psychopharmacology or individual or family therapy is particularly useful in cases of some preexisting mental illness, family conflicts, or multiple major stressors.

Few families will present with psychological distress or behavioral problems that cannot be successfully managed with routine psychosocial care along with some provision for brief intensive interventions. Usually families that cannot be managed in this way are those with many other stressors occurring at the same time or families that include an individual with a preexisting psychiatric disorder, such as major mental illness, substance abuse, or severe personality disorder. When families have multiple stressful events occurring simultaneously, such as a second illness in the family, a major loss, or economic instability, they may require more psychosocial support at the cancer center, as well as referral to additional outside agencies. Preexisting psychiatric disorders should be evaluated as part of the psychosocial assessment. Vulnerable persons at high risk for worsening of symptoms or relapse should be referred for mental health treatment or counseled about the need to access treatment quickly if symptoms recur. Communication between the psychosocial providers on the oncology team and outside mental health providers can be helpful to share a common understanding of the child’s cancer treatment status and updates about the mental health status of the family member in treatment, but this communication needs to be undertaken in a limited manner that preserves privacy.

Families with consistently active psychosocial needs can present a challenge to the care team because of their emotional distress and the demands they may make on staff time. By providing consultation to the nursing and oncology staff, the psychosocial care provider can help the treatment team formulate an understanding of the family’s needs and coordinate an appropriate and consistent response.

School

Shortly after diagnosis, questions often arise regarding the child’s academic needs and how these needs will be met. Will the child be able to attend school, or will a tutor be provided until the child is able to return to the classroom? How is the treatment course likely to interfere with the child’s ability to succeed academically? Will the child meet the academic requirements to be promoted to the next grade, or is it likely that the child will need to repeat a grade? These types of questions will need to be addressed by the family, school, and medical team.

School represents an important locus for the child’s cognitive, social, and emotional development, and maintaining participation in or reconnecting with school should be a priority when planning the child’s treatment and care. For the child resuming school responsibilities can feel overwhelming given the demands of treatment. Adverse effects of treatment can have a negative impact on motivation, concentration, and processing speed, making the transition back to school challenging. Despite the issues resuming academic work promptly will minimize the disruption to academic progress and maximize the child’s ability to reengage in school-related tasks. Because many children will be unable to attend school during at least part of their treatment, home- or hospital-based tutoring along with a structured schedule that provides the child with the exact time and duration of school-related work often promotes compliance.

Parents and caregivers must commit themselves to providing the necessary structure and support to promote the child’s academic progress, even when juggling numerous other responsibilities. Parents should be encouraged to let the tutors be responsible for assisting children with their academic work and avoid the urge to “help” children with their homework. Extended absences from school can lead to increased anxiety at the time of reentry and potential avoidance behavior. Psychosocial providers can work closely with patients, parents, and school personnel to help ease a child back into school while addressing anxiety issues.

The medical team is often called upon to provide the school with relevant information about the child’s ability to attend to academic responsibilities or any vulnerability the child may have as a result of treatment (e.g., risk of infection, susceptibility to illness, and potential cognitive and/or physical deficits). School personnel may be especially anxious when the child initially returns to school, resulting in multiple calls to the treating physician. Parents will play a critical role in educating the school about their child’s situation and advocating for the child’s needs. Many parents benefit from consultation with psychosocial providers about how best to negotiate the return to school and often find written guides for parents to be helpful. Some clinics have established “school reentry” programs in which staff members (e.g., child life, nursing, and mental health professionals) visit schools to present information to teachers and classmates about the child’s diagnosis and treatment. This proactive approach can be effective in providing medical information to the school nurse and other staff, as well as helping to answer questions that teachers and classmates may have about the returning child’s condition and needs. In most cases, these efforts will result in a plan for school reentry that is appropriate and comfortable for the child and parents.

If a child will need specialized instruction because of his or her illness or consequences of treatment, an individualized education plan (IEP) will be required. Federal laws, as well as the laws in several states, require that children with disabilities be accommodated in their schools, and parents who suspect their child will need some accommodation should speak with the school’s special education director and refer to their state’s Department of Education website for information about the special education procedures in their location. In most cases, parents will need to begin the process by making a written request for an evaluation. This evaluation is conducted by the school, often with significant input from medical and psychosocial providers involved in the child’s cancer treatment. If as a result of the evaluation the child is found to be eligible for special education services, an IEP will be developed and implemented by the school. If the child does not qualify for specialized education services, he or she may still qualify for accommodations under the Federal Rehabilitation Act, often referred to as a “504 plan.” A 504 plan may ensure appropriate accommodation for problems in physical mobility, fatigue, attendance, or other needs of the child that affect school performance but do not require specialized instruction. The IEP determination process can be time consuming and frustrating for parents who have already had to negotiate complex health and insurance systems for their child. Parents should educate themselves about their state’s education laws and the federal laws that govern accommodation of children with medical conditions and disabilities and consult with psychosocial providers who understand the system and academic needs. If significant issues are encountered in securing appropriate accommodations, parents may want to consider enlisting the services of educational advocates to assist them in negotiating with their school.

Peer Relationships

Relationships with peers at any developmental level provide a child or adolescent with crucial components for successful adaptation, including a sense of connection, friendship, and support. This role of peer relationships is as true for children diagnosed with cancer as it is for their healthy peers. Several research studies have focused on the role of peer relationships in the coping and adjustment of children and adolescents with cancer. Although parents have been identified as a primary source of nurturance, support, and information for children with cancer, research findings suggest that relationships either with healthy peers or with peers diagnosed with cancer are also extremely important. For example adolescents diagnosed with cancer who report close friendships have been noted to experience increased social support, increased feelings of hope, and an ease in communicating about their cancer experience. Additional research suggests that adolescents with cancer view peer relationships as vital to the continued development of their independence and identity, which are areas that can easily be derailed by illness.

Studies examining other aspects of peer interactions reveal somewhat mixed results. Some findings have suggested that both children and adolescents who are diagnosed with cancer have fewer friends than their same-aged peers and that this trend may continue after treatment has been completed. Other findings have indicated that children diagnosed with cancer may be socially isolated and withdrawn, despite the fact that their popularity and number of friendships are comparable with those of their peers. Whether these results reflect a change in the nature or quality of peer interactions because of illness-related factors (e.g., prolonged hospitalizations, significant school absences, or the inability to engage in recreational activities) is difficult to determine.

Given the importance of peer relationships in the course of normal development and the potential for disruption to these relationships during diagnosis and treatment, members of the medical team must support connections with peers whenever possible. This support may include encouraging parents to facilitate peer interactions at home and at the hospital and to work with educators to establish opportunities for the child to visit school for lunch or a single class so that peer connections can continue when the child is not well enough to attend school regularly. When appropriate, medical staff can also support an adolescent patient who wishes to share the clinic experience with a friend and invite the friend to attend an outpatient appointment. These opportunities, although often limited by the impact of treatment, help children with cancer and their peers maintain crucial relationships that will improve posttreatment adjustment. Encouraging parents to allow children and adolescents to have contact with peers who are also diagnosed with cancer can be extremely important. The Internet and social media sites can be very helpful when treatment prevents school attendance. Although parents will want to ensure that the sites that children are using are appropriate, technology that provides ways for children to share pictures, play video games with friends online, video chat, or text can be important ways for them to maintain contact with peers. Participation in summer camps or activities offered through the clinic or hospital provide opportunities for children and adolescents to enjoy activities with peers who have a shared medical experience and can improve self-concept.

Expectable Challenges during Treatment

Although psychosocial needs vary considerably between families, certain challenges commonly arise while children progress through their cancer treatment. Some of these challenges are directly related to coping with the demands of treatment, and others have to do with managing the ongoing demands of work, school, and family life while also managing the added stressors of cancer and its treatment. Understanding these challenges can help families anticipate when and how they may need to mobilize their resources. Psychosocial care providers can provide anticipatory guidance with regard to these concerns and facilitate access to appropriate intervention as needed.

Coping with Treatment and Adverse Effects

About 25 years ago, adolescents with cancer reported that their treatment and its adverse effects were the worst things about having cancer. The nausea and vomiting accompanying chemotherapy and the pain associated with procedures such as lumbar punctures and bone marrow aspirations were particularly distressing. Treatment of these adverse effects has significantly improved since then. Fairly effective antiemetic drugs are available, and for most patients, procedures are carried out after induction of light or deep sedation or general anesthesia. Despite these advances, children still find chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and various procedures to be very unpleasant and a source of significant apprehension and distress. A variety of studies have documented the effects of hypnotherapy, memory evaluation, and other behavioral therapies in reducing adverse effects in this population. Reducing procedure-related pain, anxiety, and nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy is critically important for reduction of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder, long-term pain, and psychological distress in survivors. The topics of pain and symptom management are treated more extensively in Chapter 71 .

Maintaining Child and Family Routines

Basic Needs

In the aftermath of a pediatric cancer diagnosis, family members must find ways to attend to basic needs and responsibilities. Although this process can be difficult, family members must eventually shift their focus from the diagnosed child and the isolation of the hospital room to life outside of the hospital. For many families, this process may include working to understand their insurance coverage and medical costs or negotiating with employers regarding the use of vacation or sick leave to care for their child. Grocery shopping, cleaning the house, paying bills, and keeping up with the laundry are additional activities that constitute a typical week for the average family—activities that were likely ignored or attended to by others during the early stages of diagnosis and treatment.

Transitioning from managing a medical crisis to managing the more mundane tasks of everyday life can be challenging but can also reintroduce a sense of normalcy. The reality of financial pressures can necessitate the transition back to work and create additional stress on the family system. Even with excellent insurance coverage, the costs associated with treatment can be significant, particularly for parents or caregivers who have been away from work since the child’s diagnosis.

After the initial phase of treatment, parents and caregivers typically attempt to piece together a plan that will allow the family to function effectively and attend to basic needs. This plan will likely take into account the child’s medical appointments (both scheduled and unscheduled), the child’s school reentry and ongoing attendance, parent or caregiver work responsibilities, attention to the academic and social needs of the child and the child’s siblings, and other family commitments and responsibilities. The ability of the family to successfully develop and implement this plan is dependent upon a number of factors, including characteristics of individual family members (e.g., coping style, organizational skills, and cognitive abilities), the functioning of the family as a whole (e.g., cohesion, adaptability, and flexibility), and the response of community members (e.g., a supportive network of friends, the flexibility of employers, and the commitment of school personal).

Understandably attending to basic needs and securing resources is crucial to the successful treatment of the child and the overall functioning of the family, and thus it is essential that members of the medical team support the family in their efforts to meet basic needs whenever possible. This support might include the timely completion of medical forms that will facilitate the implementation of educational services, helping eligible families secure appropriate financial resources, helping families access specialized nursing services in the home, allowing for flexibility in the scheduling of appointments to accommodate a long commute to the clinic, or simply being willing to listen empathically when parents discuss the challenges they face.

Discipline

The diagnosis and treatment of cancer in a child can disrupt every facet of family functioning, including expectations that parents have about their child’s behavior and their ability to effectively set limits and exercise appropriate discipline. Understandably many parents and caregivers are unable or unwilling to discipline their children given the difficult medical circumstances in which the family finds itself. A child’s behavioral outbursts that may include hitting, kicking, and screaming are seen as a natural consequence of a very difficult and unnatural situation. Disruptions to daily routines, invasive medical procedures, medication adverse effects, and the child’s “just feeling lousy” can provide more than sufficient rationale to let the child’s behavior remain unchecked. In addition parents and caregivers may be wrestling with their own feelings of guilt, sadness, anxiety, or exhaustion that can make it increasingly difficult to impose behavioral expectations, even for parents who previously demonstrated consistent and appropriate behavior management techniques with their children.

For children whose parents or caretakers are unable to provide effective discipline during treatment, the short- and long-term consequences can be disastrous. For example a child who does not experience appropriate limit setting may feel out of control and unsafe, leading to further behavioral disruption. Behavioral outbursts and noncompliance can interfere with medical care and have an impact on effective working relationships with staff. Inappropriate behavior can spread quickly to siblings who learn through observation that parental authority has been eroded, increasing the overall chaos within the family system. By the time the child’s treatment ends months or years later, it can be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to reestablish expectations for appropriate behavior.

To avoid these short- and long-term consequences, parents and caregivers need to provide clear and consistent expectations for their child’s behavior as quickly as possible after diagnosis. It is essential to acknowledge to the child that the pain and disruption associated with diagnosis and treatment often causes frustration, sadness, anger and despair and that this is expected. However it is equally essential to convey to the child that expressing emotions through appropriate means is imperative.