Prognostically Important Features of Colorectal Carcinoma

Rhonda K. Yantiss

Although tumor stage is the single most important prognostic factor among patients with colorectal carcinoma, a number of other findings are clinically relevant. Some features, such as status of resection margins, adequacy of resection, number of detected lymph nodes, and tumor perforation, are evident at the time of gross examination. Histologic grade, small-vessel (lymphovascular and small vein) invasion, large-vessel invasion, perineural invasion, tumor configuration, tumor budding, and satellite tumor deposits are all associated with aggressive biologic behavior, and thus, comments regarding their presence or absence should be included in the surgical pathology report. Specific types of cancer are high-grade neoplasms at risk for biologically aggressive behavior, and others are associated with underlying molecular changes. Some features, such as a host inflammatory response to invasive carcinoma, are associated with a better prognosis or reflect underlying molecular alterations that impact patient management. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss characteristics of colorectal cancer that are associated with biologic behavior.

INDEPENDENT PROGNOSTIC FACTORS DETECTED ON GROSS EXAMINATION

Adequacy of Surgical Resection

The distance from the advancing edge of the primary tumor to the surgical resection margin is defined as tumor clearance, which should be documented for each resection margin on colorectal cancer specimens. Every colectomy specimen contains at least three surgical resection margins: the ends of the luminal bowel and a soft tissue resection margin. Proximal and distal resection margins that are greater than 5 cm from the tumor are rarely associated with anastomotic recurrences and, thus, represent adequate margins. However, low-lying rectal tumors are frequently removed with narrower clearance of the distal margin because wide surgical resection may compromise the anal sphincter. Most data suggest that at least 2-cm clearance is adequate for all rectal cancers, and clearance of 1 cm or greater is generally considered sufficient for carcinomas that invade no more deeply than the muscularis propria.1,2

Soft tissue resection margins are created by surgical dissection of the colon from surrounding connective tissues, and their nature varies depending on the type of specimen removed, as described in Chapter 6. The soft tissue resection margin of colonic segments that lie entirely within the peritoneal cavity is the mesenteric margin. Right and left colectomy specimens contain a mesenteric margin as well as posterior soft tissue margins reflecting dissection of the pericolic fat from the posterior abdominal wall at the hepatic and splenic flexures, respectively. The rectum lies below the peritoneal reflection and has a circumferential (radial) soft tissue resection margin. Adequate clearance of the circumferential margin is defined as a distance of at least 0.1 cm from the tumor and its value should be specifically stated. Clearance less than 0.1 cm is defined

as a positive margin. Status of the circumferential margin is the single most important factor in predicting local recurrence of rectal cancer. A positive circumferential margin is associated with nearly a fourfold increased risk of disease recurrence and twofold risk of death from disease compared to patients with negative circumferential margins.3

as a positive margin. Status of the circumferential margin is the single most important factor in predicting local recurrence of rectal cancer. A positive circumferential margin is associated with nearly a fourfold increased risk of disease recurrence and twofold risk of death from disease compared to patients with negative circumferential margins.3

Table 9.1 Classification of Residual Disease in Resection Specimens for Colorectal Carcinoma (R) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Some patients who undergo surgery with curative intent have residual disease after treatment. The AJCC/TNM seventh edition Cancer Staging Manual qualifies residual tumor after surgery with the R classification system (Table 9.1). Pathologists may use this system to denote margins of resection, thereby allowing treating physicians to make reasonable assumptions regarding residual tumor in the patient. Microscopically (R1) or macroscopically (R2) positive resection margins on colectomy specimens likely correspond to residual microscopic or macroscopic disease in the patient, respectively.4 However, use of the RO category to denote negative surgical margins represents a departure from prior staging systems. Previous classification schemes defined RO as the absence of residual disease in the patient, but did not limit evaluation to the margins of a resection specimen. Pathologists were discouraged from using RO to denote negative surgical margins because RO status implied an absence of residual disease anywhere in the patient, including distant metastatic sites.1

Complete Excision of the Mesorectal Envelope (Adequacy of Total Mesorectal Excision)

Advances in surgical techniques and introduction of the total mesorectal excision have improved local recurrence rates and overall survival among patients with rectal cancer.5 Surgeons who perform a total mesorectal excision sharply dissect the perirectal soft tissues in the areolar plane outside the mesorectal (Waldeyer) fascia, such that the rectum, mesorectum, and all regional lymph nodes are removed entirely (Figure 9.1). Cancer operations performed in this fashion are associated with local recurrence and 5-year survival rates of 8% to 10% and 68%, respectively, compared to 20% to 30% and 48% among rectal cancers removed using older techniques.5,6 Pathologic evaluation of rectal resection specimens effectively determines the adequacy of mesorectal excision and predicts both local recurrence and 5-year survival. Thus, pathologists are increasingly asked to grossly assess the mesorectum on resection specimens, as discussed in Chapter 6.

Number of Harvested Regional Lymph Nodes

The number of lymph nodes detected in resection specimens positively correlates with overall survival among patients with stage II and stage III colorectal cancer. Five-year survival rates are approximately 76% when 18 or more lymph nodes are recovered from colorectal cancer patients with node-negative disease, compared to 62% when seven or fewer lymph nodes are detected.7 Indeed, the relationship between number of recovered lymph nodes and prognosis

is so strong that the former may represent an important criterion used to stratify patients with T3N0 colorectal cancer who are under consideration for clinical trials.8 The relationship between survival and number of harvested lymph nodes reflects a combination of two factors: stage migration and host immunity. Stage migration is a term used to describe the association between appropriate stage assessment and number of harvested lymph nodes. The likelihood of detecting metastatic lymph node deposits increases as more lymph nodes are identified, resulting in assignment to a higher pathologic stage grouping that more accurately predicts outcome. Alternatively, detection of numerous lymph nodes may reflect a host immune response to cancer, which is independently associated with improved survival.9 A robust inflammatory response to colorectal cancer induces reactive enlargement of regional lymph nodes, which facilitates their detection.

is so strong that the former may represent an important criterion used to stratify patients with T3N0 colorectal cancer who are under consideration for clinical trials.8 The relationship between survival and number of harvested lymph nodes reflects a combination of two factors: stage migration and host immunity. Stage migration is a term used to describe the association between appropriate stage assessment and number of harvested lymph nodes. The likelihood of detecting metastatic lymph node deposits increases as more lymph nodes are identified, resulting in assignment to a higher pathologic stage grouping that more accurately predicts outcome. Alternatively, detection of numerous lymph nodes may reflect a host immune response to cancer, which is independently associated with improved survival.9 A robust inflammatory response to colorectal cancer induces reactive enlargement of regional lymph nodes, which facilitates their detection.

Tumor Perforation

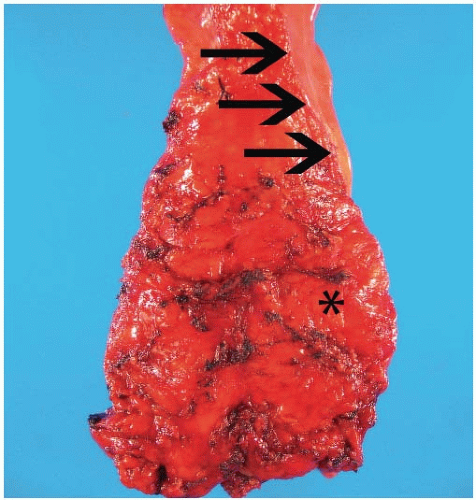

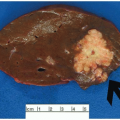

Free tumor perforation is defined by the presence of transmural necrosis and perforation at the site of an invasive adenocarcinoma. Tumor perforation is always designated pT4a and is independently associated with poor outcome.2 Although one frequently appreciates tumor perforation at the time of gross examination, tumor cells are not always readily demonstrable on the serosal surface in histologic sections.10 Similar to nonneoplastic colonic perforation, free perforation through a tumor elicits an exuberant inflammatory reaction with abscesses, a fibroinflammatory tissue reaction, and fibrin at the site of penetration that mask contamination of the peritoneal surface (Figure 9.2). Findings such as these should prompt careful examination of the gross specimen, review of the clinical information, and additional tissue sections, as discussed in Chapter 8. Tumor perforation should be distinguished from perforation of the uninvolved colon proximal to an obstructing colon cancer. Although the latter is also associated with high mortality, poor outcome reflects the frequent occurrence of generalized peritonitis and sepsis in patients with colonic perforation, rather than tumor recurrence and death from disease.2,11

HISTOLOGIC GRADING OF INVASIVE COLORECTAL CARCINOMA

Although many pathologists use “differentiation” and “grade” interchangeably, these designations are not synonymous. Differentiation describes the extent to which a cellular proliferation resembles the normal components of the organ of origin. For example, well-differentiated colonic adenocarcinomas contain mostly gland-forming elements that are similar in size and shape to nonneoplastic colonic glands, whereas poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas contain sheets of tumor cells that are not organized in well-formed glands and bear minimal, if any, resemblance to normal epithelial cells. Histologic grade, on the other hand, refers to severity of cytologic atypia as evidenced by a constellation of features including nuclear size and contour, chromatin pattern, nucleolar prominence, mitotic activity, and the presence, or absence, of necrosis. Low-grade cytologic atypia is characterized by slight nuclear enlargement with minimal nuclear membrane abnormalities, mostly dispersed chromatin, occasional prominent nucleoli, and scattered mitotic figures. Markedly enlarged, irregular, or folded nuclei with coarse chromatin and one or more large nucleoli represent high-grade cytologic features. High-grade tumors usually display easily detected mitotic figures and individual cell necrosis. Histologic grade and degree of differentiation are positively correlated in most colorectal carcinomas. Well-differentiated carcinomas tend to show low-grade cytologic features, whereas poorly differentiated carcinomas are generally high grade. However, most colorectal adenocarcinomas show a greater degree of cytologic atypia relative to gland formation compared to adenocarcinomas of other organs.

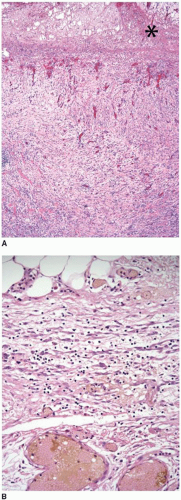

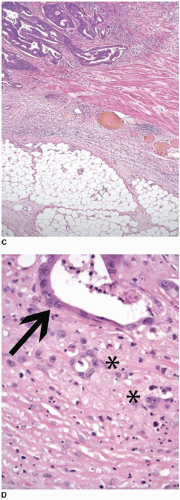

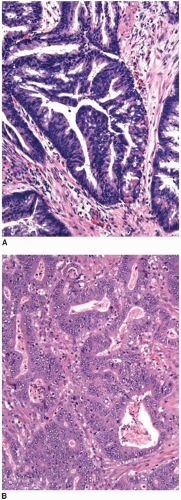

The most widely accepted colorectal cancer grading scheme is based solely on extent of glandular differentiation within the neoplasm because lack of gland formation has adverse prognostic significance independent of tumor stage.12 The WHO considers carcinomas that contain >95% glandular elements to be well differentiated, whereas those with 50%-95%, 5%-49%, and <5% gland formation are classified as moderately, poorly, and undifferentiated carcinomas, respectively (Figure 9.3).13 Unfortunately, this grading system suffers from a substantial degree of interobserver variability, particularly with respect to the distinction between well- and moderately differentiated carcinomas. Thus, the AJCC/TNM seventh edition Cancer Staging Manual recommends that this four-tiered system be collapsed into a two-tiered system (Table 9.2).4 The low-grade category includes well-to-moderately differentiated carcinomas, whereas poorly and undifferentiated tumors are classified as high-grade malignancies.

The most recent WHO colorectal carcinoma grading system also incorporates defective mismatch repair mechanisms into its classification scheme.13 Carcinomas that are microsatellite stable (MSS) are graded based solely on degree of glandular differentiation as described above, whereas those with high-frequency microsatellite instability (MSI-H) are considered to be low grade, regardless of the extent of gland formation (Figure 9.4). Inclusion of molecular features in histologic grading schemes represents a major departure from traditional criteria, although incorporating microsatellite status into grade assessment reflects the generally favorable prognosis associated with MSI-H tumors.14,15

Colorectal carcinomas are morphologically heterogeneous, and the methods used to assess grade vary widely among different practices. Colorectal carcinomas tend to be better differentiated superficially, whereas the invasive front typically shows less gland formation. Some pathologists base classification on the extent of gland formation throughout the tumor, whereas others limit their evaluation to areas that are less differentiated. The WHO considers the advancing edge of the tumor to be suboptimal for grade assessment, and as a result, pathologists have historically neglected this region when evaluating colorectal cancers for histologic grade.13 However, recent data suggest that failure to assess the advancing tumor front likely underestimates biologic potential among colorectal carcinomas. Tumors composed of

more than 50% gland-forming elements may behave aggressively, despite their classification as low-grade (moderately differentiated) cancers. Indeed, tumors that contain non-gland-forming elements occupying at least one high-power field (400× magnification) are associated with a 69% disease-related 5-year survival, compared to 99% 5-year survival among patients with cancers containing fewer than 10 solid tumor cell clusters per low-power field (40× magnification).16 These observations have led to alternative grading schemes based on objective criteria that specifically assess extent of non-gland-forming elements, rather than glandular differentiation. One such model quantifies the number of solid cell clusters containing five or more tumor cells, regardless of where they are located in the mass (i.e., advancing edge or elsewhere). Tumors with <5, 5-9, and ≥10 cell clusters per intermediate power field (200× magnification) are classified as G1, G2, and G3, respectively. When applied to stage II and stage III colorectal carcinomas, these grade assignments are associated with 5-year disease-free survival rates of 96%, 85%, and 59%, respectively.17

more than 50% gland-forming elements may behave aggressively, despite their classification as low-grade (moderately differentiated) cancers. Indeed, tumors that contain non-gland-forming elements occupying at least one high-power field (400× magnification) are associated with a 69% disease-related 5-year survival, compared to 99% 5-year survival among patients with cancers containing fewer than 10 solid tumor cell clusters per low-power field (40× magnification).16 These observations have led to alternative grading schemes based on objective criteria that specifically assess extent of non-gland-forming elements, rather than glandular differentiation. One such model quantifies the number of solid cell clusters containing five or more tumor cells, regardless of where they are located in the mass (i.e., advancing edge or elsewhere). Tumors with <5, 5-9, and ≥10 cell clusters per intermediate power field (200× magnification) are classified as G1, G2, and G3, respectively. When applied to stage II and stage III colorectal carcinomas, these grade assignments are associated with 5-year disease-free survival rates of 96%, 85%, and 59%, respectively.17

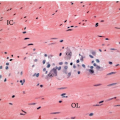

FIGURE 9.3: Low-grade adenocarcinomas include well- and moderately differentiated tumors that contain greater than 95% (A) and 50% to 95% (B) gland-forming elements, respectively. |

FIGURE 9.3: (Continued) (C) High-grade carcinomas are poorly differentiated malignancies with less than 50% gland formation or undifferentiated cancers that show rare (<5%) glands (D). |

Table 9.2 Grading Scheme for Classification of Colorectal Adenocarcinomas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

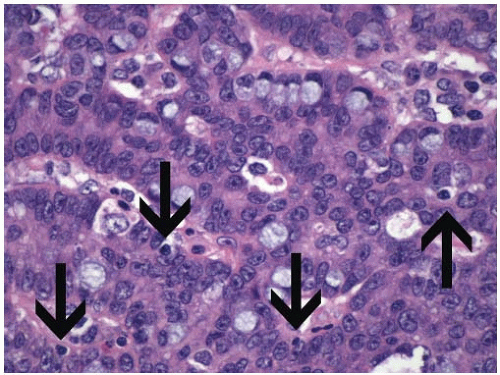

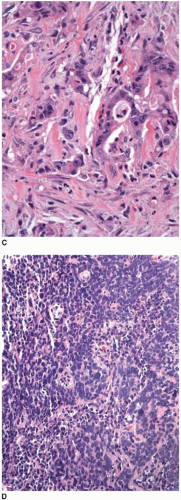

HISTOLOGIC GRADING OF SPECIFIC CANCER SUBTYPES

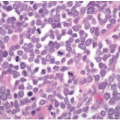

Some morphologic subtypes of colorectal carcinoma are, by definition, classified as low- or high-grade neoplasms based on their biologic behavior and molecular features. For example, medullary carcinomas are poorly differentiated inasmuch as they lack glandular differentiation, yet this phenotype is associated with improved survival compared to other colorectal carcinomas with minimal gland formation (Figure 9.5A). Medullary carcinomas are usually MSI-H and, thus, are classified by the WHO as low-grade carcinomas despite their lack of glandular differentiation.13 On the other hand, signet ring cell, (neuro)endocrine (small cell), and undifferentiated colorectal carcinomas are considered to be high-grade malignancies because they are associated with poor survival (Figures 9.5B and 9.5C).18,19 More than 75% of patients with signet ring cell carcinoma have regional lymph node metastases at the time of diagnosis, and 30% to 60% present with disseminated peritoneal disease.20 Nearly 70% of patients with high-grade (neuro) endocrine carcinoma have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. One-, two-, and three-year survivals are approximately 46%, 26%, and 13%, respectively, and the mean survival is only 10.4 months.18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree