Number of Positive Lymph Nodes

The number, size, and location of positive cervical lymph nodes define the N stage for HNSCC and provide important information regarding prognosis and selection of treatment. The number of cervical lymph nodes histologically positive for squamous cell carcinoma provides one of the simplest, and perhaps most important, prognostic markers in head and neck cancer. Mamelle et al. retrospectively reviewed 914 patients who received cervical lymph node dissection as a component of initial therapy for oral cavity, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal SCC.

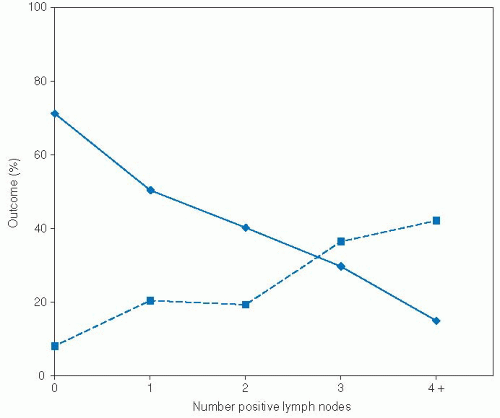

121 Patients with palpable lymph nodes >3 cm underwent radical lymph node dissection, and all other patients underwent selective neck dissection on sentinel nodes with immediate pathologic evaluation. Those patients with positive sentinel nodes then received ipsilateral modified radical neck dissection and contralateral selective neck dissection. Thus, all patients, regardless of their clinical N stage, received pathologic evaluation of their cervical lymph nodes. Those patients with positive cervical lymph nodes received 50 Gy to the neck with a 15 Gy boost in areas of extracapsular spread. In this study, lymph node number exhibited a strong dose-response correlation with distant metastasis and survival (

Fig. 3-1). In multivariate analysis stratified by tumor site and patient age, number of positive nodes was a significant, independent predictor of survival. Furthermore, although extracapsular spread and node location (upper vs. middle vs. lower neck) were significant predictors of survival in univariate analysis, after controlling for number of positive lymph nodes,

they lost their prognostic significance. Thus, with this particular treatment algorithm, the number of positive nodes emerged as an important, independent predictor of prognosis.

The importance of positive cervical nodes has been noted in many other studies and appears to correlate with risk of regional recurrence and distant metastasis. Studies have demonstrated a correlation between increasing number of positive nodes and regional recurrence in patients with advanced SCC who receive postoperative radiotherapy,

122 patients who do not receive radiotherapy,

64 patients with oral cavity

30 and hypopharyngeal or lateral epilaryngeal primary tumors,

123 and patients who receive neck dissection for mucosal HNSCC from any site.

124,125 Furthermore, number of positive nodes clearly predicts risk of distant metastatic disease for all sites of HNSCC.

11,108,121,126,127,128,129,130 Number of positive nodes predicts both regional recurrence

64 and distant recurrence,

129 even after controlling for other prognostic variables in multivariate analysis.

Finally, the number of positive cervical lymph nodes consistently correlates with survival in univariate analysis for all major sites of HNSCC.

9,30,62,122,123,126,131,132,133,134,135 The relative importance of ECE versus number of positive nodes remains somewhat controversial. In addition to the Mamelle et al. study,

121 Moe et al. found the number of positive nodes to predict poor survival independent of ECE in 159 patients with advanced laryngeal cancer.

11 However, cohorts of 136 patients with clinically node positive oral cavity cancer

63 and 281 patients with supraglottic cancer

46 found that ECE, not number of positive nodes, was an independent predictor of poor survival. Differences in treatment modalities and stratification of pathologic variables may explain some of the differences noted in these studies. Regardless, patients with either multiple positive lymph nodes or ECE are at higher risk for recurrence and should be considered for aggressive therapy.

Extracapsular Extension

ECE occurs in roughly 60% of patients with positive cervical nodes and is of paramount importance in predicting patient outcomes.

136,137 A recent study of 337 patients reported a strong association between the presence of ECE and clinical N stage, with ECE present in 10.5% (18/171) of clinical NO patients, 35% (26/75) of clinical N1 patients, 55% (35/64) of clinical N2 patients, and 74% (20/27) of clinical N3 patients.

135 The extent of ECE can be stratified into the following three levels based on the morphology of the involved cervical lymph nodes: (a) macroscopic extracapsular spread with involvement of adjacent anatomic structures such as the internal jugular vein or skeletal muscle, (b) macroscopic extracapsular spread confined to the perinodal fibro-adipose tissue, and (c) microscopic extracapsular spread.

22 A recent study of 96 dissected cervical lymph nodes with ECE measured the maximum distance from the capsule border to the farthest extent of the tumor.

138 The mean extension was 2.2 mm, and in 96% of lymph nodes the maximum extension was <5 mm. Rarely, the extension measured up to 9 mm. These findings have important implications for target delineation in the setting of intensity modulated radiation therapy to treat lymph nodes at high risk for ECE.

As a general marker of tumor invasiveness and biologic aggressiveness, some authors have proposed that the presence of ECE in cervical lymph nodes may predict recurrence at the primary site. This hypothesis remains unresolved, as two studies conducted on a total of 207 patients with laryngeal cancer noted a significant association between ECE and local recurrence,

139,140 but two other studies conducted on a total of 392 HNSCC patients failed to confirm this association.

123,136Regardless of its relationship with local recurrence, ECE is a significant determinant of prognosis due to its association with increased risk of recurrence in the neck and distant metastatic disease. For example, in a review of 284 patients with HNSCC who received neck dissection as a component of initial therapy, the presence of gross or microscopic ECE tripled the risk of neck recurrence in multivariate modeling.

64 In addition, patients with gross ECE were 1.5 times more likely to develop regional recurrence when compared to patients with microscopic ECE, although this trend did not reach statistical significance. Many other series have confirmed this relationship for the following sites: oral tongue,

22 oral cavity and oropharynx,

5,29 hypopharynx and lateral epilarynx,

123 pyriform sinus,

9 supraglottic larynx,

139,141 larynx,

140,142,143 and all sites combined.

70,122,124,125,144 The association between ECE and regional recurrence is independent of other prognostic variables in HNSCC.

64,125,142The presence of ECE also increases the risk of distant metastatic disease. In a review of 281 patients who received a neck dissection as a component of initial therapy for HNSCC, the presence of ECE tripled the risk of distant metastasis as the first site of failure (19.1% in ECE positive patients vs. 6.7% in ECE negative patients).

127 These findings have been reproduced in several large studies.

108,126,128,135,145 Currently, it is unclear whether the relationship between ECE and distant metastatic disease is independent of the number, size, and location of positive cervical lymph nodes.

In addition, ECE is a significant predictor of poor disease-free, cause-specific, and overall survival. In a retrospective study of 281 patients with supraglottic SCC treated with surgery with or without postoperative radiotherapy, pathologic NO patients experienced a 5-year overall survival of 65%, compared to 49% in node-positive patients without ECE and 20% in node-positive patients with ECE.

46 In a multivariate model, the presence of ECE conferred the highest risk of death, resulting in a sixfold increased risk of death when compared with node-negative patients. In contrast, patients with positive nodes but no ECE experienced a threefold increased risk of death. This independent association between ECE and poor cause-specific or overall survival has been confirmed for the following sites: oral cavity,

63 oral cavity and oropharynx,

5 supraglottic larynx,

62 larynx and hypopharynx,

143 and all sites combined.

49,125,142The importance of ECE as compared to other pathologic factors was underscored in a prospective randomized clinical trial conducted by Peters et al. that evaluated radiation dose in the postoperative setting.

146 In this trial, patients with ECE experienced significantly higher local-regional recurrence rates than patients without ECE. In addition, in the subset of patients without ECE, only those patients with four or more adverse risk factors experienced a local-regional recurrence rate comparable to those patients with ECE. Adverse factors examined included oral cavity primary, close or positive margins, PNI, two or more positive nodes, largest node >3 cm, Zubrod score ≥2, and delay in starting radiotherapy. As a result, the study authors concluded that ECE is the dominant pathologic risk factor in HNSCC. Furthermore, this study showed that, in patients with ECE, localregional control increased from 52% to 74% as dose increased from 57.6 to 63 Gy. No such dose-response was evident for patients without ECE, suggesting that tumors with ECE require a higher dose of postoperative radiation to achieve adequate localregional control.

Due to the poor prognosis associated with ECE, several investigators have explored the potential benefit of postoperative chemoradiation in this patient population. The first randomized data to support a benefit of chemoradiation was reported by Bachaud et al. in 1996.

147 This trial included 83 patients with histologically documented ECE treated with surgery and postoperative radiation with or without concurrent cisplatin (50 mg given weekly with radiation for seven to nine cycles). The addition of cisplatin lowered the risk of local-regional recurrence, from 41% in the radiation alone group down to 23% in the chemoradiation

group. Subsequently, large multicenter trials conducted by the Radiation Therapy and Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) randomized patients with high-risk, resected head and neck cancer to receive postoperative radiation or postoperative radiation with concurrent cisplatin (100 mg/m

2 given on days 1, 22, and 43).

58,59 A

post hoc pooled analysis revealed that the addition of cisplatin was specifically beneficial for patients with ECE, lowering the relative risk of local-regional recurrence by 50% and also improving overall survival.

60 The updated data on the RTOG 9501 Intergroup Phase III trial has failed to show an overall benefit to the addition of chemotherapy, with a median follow-up of 9.4 years.

148 However, the subgroups with positive resection margins or extracapsular spread did have improved loco regional control with the addition of chemotherapy.

Node Location

The anatomic location of positive cervical lymph nodes has been classically described by dividing the neck into five anatomic levels.

149 Level I refers to nodes within the submandibular and submental triangles. Levels II, III, and IV refer to the chain of nodes along the upper, middle, and lower third of the jugular vein, respectively. Level V refers to nodes along the spinal accessory nerve and within the posterior cervical triangle. Using these categories, Mamelle et al. defined sentinel nodes as those nodal groups that provide the primary lymphatic drainage for a particular site within the head and neck.

121 Thus, sentinel nodes for oral cavity tumors were defined as levels I, II, and III; and sentinel nodes for oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal tumors were defined as levels II and III. Applying this classification to cervical node pathologic specimens from 914 HNSCC patients, Mamelle et al. found that the presence of nodal metastases outside the sentinel node region independently decreased 5-year survival by more than 50% and nearly doubled the rate of distant metastasis. Furthermore, node location inside versus outside of the sentinel area predicted survival independent of number of positive nodes and extracapsular spread. The increased risk of regional recurrence, distant recurrence, and death associated with positive low cervical lymph nodes has been noted in several other studies of patients with HN-SCC.

11,36,123,129,131,132,134,150,151 Setton

152 reported that low-lying cervical metastases (levels IV, VB) were independent predictors of distant metastasis. Finally, de Bree et al. found that 33% of HNSCC patients with low jugular lymph node metastases showed evidence of concomitant distant metastatic disease on preoperative CT of the thorax.

1 Clearly, patients with positive lymph nodes outside of the sentinel node regions merit aggressive preoperative screening for distant disease and are at increased risk of treatment failure and death following aggressive local-regional therapy.