CHAPTER 42 Preventive Healthcare and Management of Chronic Diseases in Adults

Introduction

Complex interactions between the patient, the healthcare delivery system, and providers all have an impact upon both the ability to, and interest in, participating collaboratively in preventive healthcare and aggressive chronic disease management. This chapter will highlight the dangers of generalization and the need for a disciplined, consistent approach to health promotion and prevention, as well as chronic disease management. Well-documented disparities in preventive healthcare and in chronic disease outcomes exist for immigrants, even after correcting for access to care. Issues of access and language are key determinants of use of preventive health services and chronic disease management, and are discussed elsewhere in detail in this text. However, interesting data on cultural considerations in preventive healthcare and chronic disease management exist, and can assist with the design of culturally competent prevention and treatment programs.

Preventive Services and Chronic Disease Management: General Considerations

Access to care

Racial differences in access to care are a primary contributor to health disparities for immigrants, particularly for the undocumented. However, even after correcting for access to care, minority patient outcomes are worse than majority.1 For example, in one study of primary care office visits utilizing National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys between 1985 and 2000, neither patient HMO membership nor physician HMO participation was greatly associated with racial disparities in primary care.2 This study concluded that changes in HMO membership alone are unlikely to affect disparities in receipt of primary care, for better or for worse.

While the healthy migrant effect has been confirmed in national studies (see Ch. 3), less use of the healthcare delivery system by immigrants is complex and multifactorial, reflecting barriers of access, language, and cultural beliefs which may clash with American healthcare. It is also difficult to separate data specifically for refugees after immigration, as they become subsumed under the foreign-born, or immigrant category.3

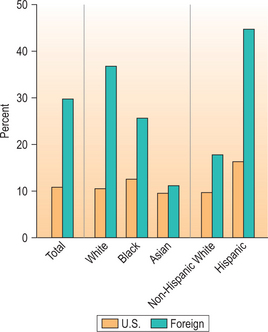

Health insurance facilitates access to care. The uninsured report more problems getting care, have poorer health status, and are diagnosed at later disease stages (Fig. 42.1).1

Language, transportation, and cross-cultural barriers

Other barriers to care include language, transportation, and cross-cultural issues between providers and patients.4 Age, gender, country of origin, and length of time in the US all have been shown to impact immigrants’ utilization of healthcare services. A recent survey of Latinos in Philadelphia showed income and education determined having health insurance, time in the US and health insurance determined having a regular source of care, and having a source of care and being female determined visits to the doctor in the past year.5

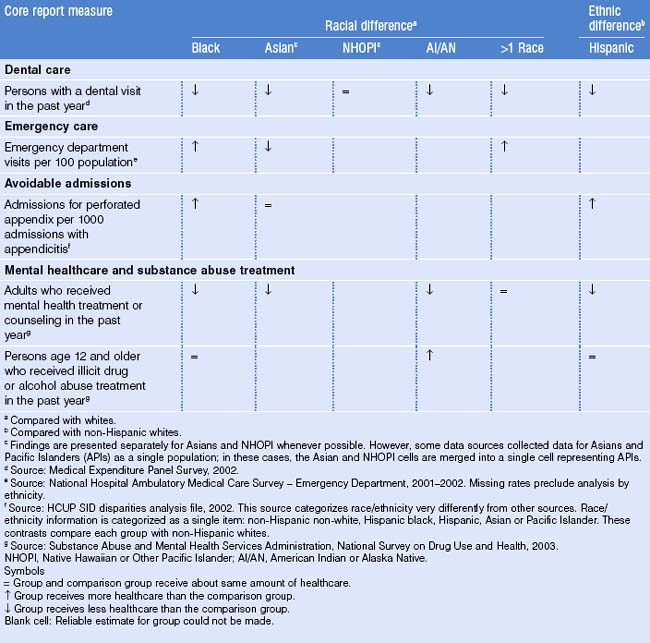

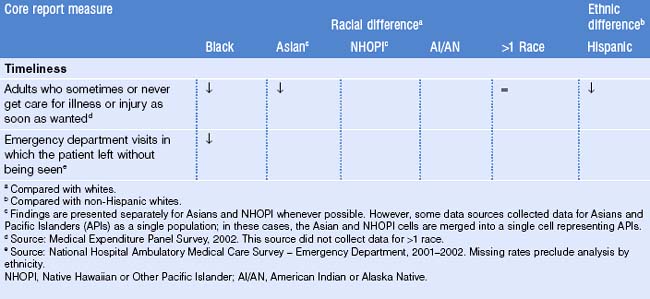

Racial differences in utilization of care are summarized in data from the 2005 National Health Care Disparities report, shown in Table 42.1.

A study of elderly Chinese immigrants in Boston revealed that patients underutilized services for multiple complex reasons including language, transportation, cost, long waits for appointments, and cross-cultural issues including fear and distrust of Western medicine.6 A prospective study of behavioral risk factors and preventive healthcare practices of immigrants seen in the emergency department at Bellevue Hospital Center, New York, revealed that immigrant women were more likely never to have had a Papanicolaou test (16.1% versus 1.4%) and never to have performed a breast self-examination (20.8% versus 7.5%). Immigrants were more likely not to use condoms (63.4% versus 42.8%) and never to have visited the dentist (21.2% versus 7.8%). These differences were independent of age, gender, marital status, employment, education, income and health insurance status. When analyzing the immigrant group alone, region of origin, length of time in the United States, and English ability were significant independent predictors of higher-risk behavioral profiles and poorer preventive healthcare practices.7

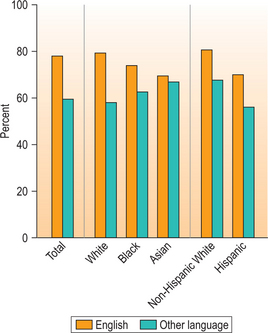

Language, job security, and education top the list of concerns for immigrants in successfully adapting to life in a new country. Language is a primary barrier to care, and is related to probability of having a primary care provider (Fig. 42.2).

Unequal treatment

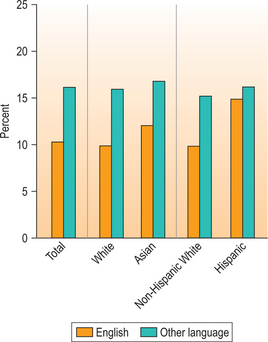

In a national survey of physicians in 2002, the majority of doctors tended to say the healthcare system ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ treats people unfairly based on various characteristics such as race/ethnicity, language, or country of origin, though significant minorities of physicians, including female physicians and physicians of color, disagreed.8 African-American physicians, for example, were much more likely than other physicians to be aware of existing disparities in treatment for heart disease and HIV/AIDS based on race. Doctors who said racial and ethnic disparities happened at least ‘somewhat often’ were most likely to say that a lack of doctors in minority communities and communication difficulties were the primary reasons. Providers are not alone in this belief: in a nationally representative sample of Americans age 18 or over, 68% of Americans were unaware that disparities in the quality of healthcare exist.9 Forty-four percent of African- Americans and 56% of Hispanics/Latinos felt they received worse care than whites. Patients’ perceptions of bias on the part of providers have been shown in other studies. In a study from the Commonwealth Fund in 2002, African-Americans (15%), Hispanics/Latinos (13%), and Asian-Americans (11%) were more likely than whites (1%) to feel they are treated with disrespect when receiving healthcare, experience barriers to access to care such as lack of insurance or not having a regular doctor, and feel they would receive better care if they were of a different race or ethnicity (Fig. 42.3).10

Pre-emigration healthcare experiences

Generational status, pre-emigration healthcare experiences, and acculturation all play a role in utilization of services. Elderly immigrants from the former Soviet Union extensively utilized health services in one study.11 Providing support for depression and loneliness, educating immigrants about the role of primary care providers in the US as well as realistic expectations of American medicine, and managing care to decrease the use of unnecessary services were all recommended.

One intriguing study of Russian-speaking immigrants across three age groups demonstrated that immigrant women accessed healthcare services based on their patterns of utilization in their countries of origin. Younger and middle aged women tended to utilize the emergency room for episodic care, and older women accessed services at clinics.12 Lack of connection to a specific primary care provider or clinic, as previously outlined, is a barrier to care for immigrants.

Perceptions of health services attributes were influenced by families’ sociocultural referents and pre-emigration experience in one study of immigrants to Montreal. The primary attributes upon which families based their evaluation, selection, and adoption of health services were geographical and temporal accessibility, interpersonal and technical quality of services, and language spoken by health professionals and staff.13 Many immigrants come from countries where appointments were not utilized, and expectations of the ability to walk in for care without an appointment persist after arrival in the US. Timeliness of care differs by race and ethnicity in the United States, as shown in Table 42.2.

In one study of Bosnian immigrants (more than 300 000 of whom have come to the United States since the 1990s), participants were universally critical of the US system and compared their experience with prewar Bosnian healthcare. They were specifically critical of confusion about health insurance coverage, lack of personalized quality of care, access to primary and specialty care, and a perception of US healthcare as bureaucratic.14 In 150 Latino immigrant families, even perceived social acceptance, such as being identified as Latino, affected health behavior, emphasizing the complexity of factors which interplay in health behavior.15

Cultural issues affecting use of preventive services

Concepts of prevention vary across cultures, are complex and multifaceted, and relate to beliefs about disease causation. In many immigrant communities, the Western biomedical model of disease causation is alien, and illness may be thought due to bad karma, soul loss, curses such as the evil eye, or punishment for wrong-doing in a previous life (see Chs 7 and 8). Concepts of disease prevention and treatment exist in all cultures, and are based on belief systems of disease causation.

Patients therefore may not be coming to a Western provider with a desire for obtaining a diagnosis (they may already have a belief about what is causing their illness), but specifically for symptom relief. In many cultures, any procedures done in the setting of lack of symptoms, such as mammography and colonoscopy, are considered invasive and unnecessary. A focus group with Iranian women in Sweden revealed that complex relationships and reasoning about health maintenance and disease prevention were related to perceptions of body and self, and to the continual construction of social roles throughout the lifespan. ‘Cultural’ differences in cancer prevention behavior appear to have been as related to social roles and phases in the life cycle as to ethnicity. Providing information which focused on potential serious diagnoses, such as ‘we may find an early cancer,’ was viewed as leading to negative outcomes.16

‘I didn’t see doctors even when I had high blood pressure, colitis and other problems – since they are all chronic. I know all about the drugs, diet, etc. I have some prescription drugs at home; friends buy them for me in Russia. So you can figure out yourself that I have no time and no right mindset for preventive check ups. I just take it easy – what will be, will be’.

Preventive health concerns were low on the personal agenda of female immigrants, burdened by more immediate needs including income, housing, and support of other family members. Other barriers included lack of referral from primary care providers, fear of cancer diagnosis, apprehension regarding irradiation and pain involved in mammography, a fatalistic general attitude toward health and illness, and distrust of current cancer therapies. Older women (60+), whose risks were actually higher, shared a false belief that breast cancer strikes younger women and that they were already past the age of concern. Older informants avoided gynecological clinics because of the male gender of most gynecologists, their poor command of Hebrew, and a belief that gynecological checkups were irrelevant and even shameful at their age. The study concluded that female immigrants, particularly older ones, must be a special target group for preventive health interventions.17 In another study, intervention with socioculturally tailored breast health articles in Urdu and Hindi in South Asian community newspapers resulted in improved self-reporting of ‘ever had’ routine physical checkup, clinical breast examination, and knowledge, as well as decreased misperception of low susceptibility to breast cancer, and short survival after diagnosis.18

In an editorial by Dr. Antonella Surbone, an oncologist from Italy, the observation was made that what is beneficent from a Western biomedical ethics perspective – that patients are given informed consent for diagnosis and treatment of cancer – may actually be maleficent in other cultures.19

End-of-life care/advance directives

Research has identified three basic dimensions in end-of-life treatment that vary culturally: communication of ‘bad news’; locus of decision-making (individual versus extended family/community); and attitudes toward advance directives and end-of-life care.20

Bosnian immigrants in one study were interviewed about their views of physician–patient communication, advance directives, and locus of decision-making in serious illness.21 ‘It’s like playing with your destiny,’ one immigrant stated. Many indicated they did not want to be directly informed of a serious illness. There was an expressed preference for physician- or family-based healthcare decisions. Advance directives and formally appointed proxies were typically seen as unnecessary and inconsistent with many respondents’ personal values. Findings of this study suggested that the value of individual autonomy and control over healthcare decisions may not be as applicable to cultures with a collectivist orientation. Designing care to be patient-centered is one of six key recommendations from the Institute of Medicine’s Quality Chasm report,22 and yet to do so can create direct conflicts with Western biomedical ethical principles including the principles of autonomy and informed consent. Provision of effective informed consent for patients with limited health literacy has been improved via a ‘teach back’ method, in which patients are asked to recount information during the informed consent process, in order to demonstrate their level of understanding.23

Unfamiliarity with services

Immigrants may not be as aware of existing community resources, including health promotion resources. In the 1999 National Survey of America’s Families, compared to US-born citizens, immigrant citizens were at highest risk of not being aware of health and community resources for most outcomes.24 Parental race/ethnicity, education level, employment status, and child age were other significant independent risk factors. This study clearly documented disparate awareness among parents of different immigrant status. Recommendations were made that community and health resources should reach out to immigrant populations, in linguistically and culturally appropriate ways, to alert them to the availability of their services. In one study of the effectiveness of a community-based advocacy and learning intervention for Hmong refugees, participants’ increased quality of life could be explained simply by their improved satisfaction with existing resources of which they had been previously unaware (Table 42.3).25

Table 42.3 Selected factors shown to contribute to differences and disparities in preventive health services for immigrants

| Patient issues | Care delivery systems issues | Provider issues |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Access/lack of health insurance | Lack of financial alignment to encourage or support providers caring for immigrants |

| Gender | Lack of organizational commitment to disparities reduction | Lack of language concordant providers |

| Language ability | Lack of adequate spoken language resources | Lack of knowledge of immigrant groups’ medical issues based on race/ethnicity or country of origin |

| Competing needs: housing, job, education | Lack of adequate data collection on outcomes and satisfaction by population | Lack of knowledge of immigrant groups’ cross-cultural issues |

| Transportation | Lack of adequate reimbursement for care and services | The culture of Western biomedicine |

| Cross-cultural beliefs | Lack of adequate resource allocation for safety net populations (social workers/case management/community health workers) | Lack of diverse providers reflecting the cultural perspective of communities served |

| Lack of knowledge of existing resources | Location in areas of need | Time pressures |

| Fear, lack of trust, perceptions of bias, stereotyping and racism | Lack of adequate written language materials | Lack of access to educational resources on a real time basis |

| Previous experiences with health services in country of origin/region of origin | Lack of culturally competent outreach and education programs | Attitudinal issues, including bias, racism and stereotyping |

| Length of time in the US | Lack of connection to communities being served |

The healthy migrant effect and chronic health conditions

In general, many immigrants arrive in the US healthy (unless they are older immigrants) and their health gradually erodes over time (see Ch. 3). A Canadian study revealed that there is robust evidence that the healthy immigrant effect is present for chronic conditions for both men and women, and results in relatively slow convergence to native-born levels. Region of origin was an important determinant of immigrant health. The healthy immigrant effect was thought to reflect convergence in physical health rather than convergence of screening and detection of existing health problems.26 The paradoxically low mortality of recent immigrants may be in part due to a temporal advantage. Mortality from treatable, communicable, and maternal conditions, so high in many countries of origin, quickly declines to levels close to those of the host country. Mortality from ischemic heart disease, the most common cause of death in industrialized host countries, takes years to decades to rise to comparable levels. After adopting a Western lifestyle, immigrants face an increasing risk of ischemic heart disease.27 In one study, Canadian ‘new immigrants’ (those who immigrated less than 10 years previously) had better health than their longer-term counterparts (those who immigrated 10 or more years previously), whose health status was similar to that of Canadian-born persons. Older (age 65 and over) recent immigrants had poorer overall health compared to Canadian-born persons.28 A longitudinal analysis of health status and healthcare for immigrants in Canada revealed that health status of immigrants quickly declined after arrival, with a concomitant increase in use of healthcare services.29 In a US National Health Interview Survey on Asian and Pacific Islander health, the immigrant health advantage consistently decreased with duration of residence.30 For immigrants whose duration of residence was less than 5 years, 5–10 years, and 10 years or more, the odds ratios for activity limitations were 0.45, 0.65, and 0.73, respectively. Subgroup analysis noted that Pacific Islanders and Vietnamese were found to have less of a healthy immigrant advantage on US arrival.

Country of origin as a predictor of health

In one intriguing study, the ability to disaggregate health status of black Americans into subgroups (US-born blacks, black immigrants from Africa, the West Indies and Europe) revealed differences in the status of US-born and foreign-born blacks compared to that of US-born whites on three measures of health: US-born and European-born blacks had worse self-rated health, higher amounts of activity limitation, and higher odds of limitation due to hypertension compared to US-born whites.31 In contrast, African-born blacks had better health than US-born whites on all three measures, while West Indian-born blacks had poorer self-rated health and higher odds of limitation due to hypertension, but lower odds of activity limitation. The study concluded that grouping together foreign-born blacks may result in missing important variations within this population. The black immigrant health advantage varied by region of birth, and by health status measure.

Self-ratings of health status

Data from the 1992–1995 National Health Interview Surveys revealed significant differences in health characteristics between groups classified by race and nativity.32 Over 87% of foreign-born black persons assessed their health as excellent to very good, compared with 52% for US-born black persons, and similar to US- and foreign-born white persons (69% for each group). Eleven percent of foreign-born black persons were limited in performing some type of activity, compared with 20% of their US-born counterparts. Among white persons, 14% of foreign-born and 16% of US-born individuals were limited in activity. The study concluded that information about the nativity status of black and white populations may be useful in public health efforts to eliminate health disparities. Most health systems collect data by race and ethnicity, rather than by country of origin, and important population differences may be lost as a result.

Disease Prevention/Health Promotion

The danger in generalizing among various immigrant groups

Different immigrant groups have different health behaviors. In one study of newly arrived (less than 90 days) adult refugees in United States, rates of overweight were highest among Bosnians and lowest among Vietnamese.33 Cubans reported the most physical activity and Kosovars the least. Rates of smoking were highest among Bosnians and lowest among Cubans. Older refugees were more overweight and reported less physical activity and more smoking than younger adults. The study concluded that different groups have different health promotion needs. A 2005 telephone survey of middle-aged and older Asian Indian immigrants to the US showed that average length of residence in the US was over 25 years.34 Fifty-two percent were of normal weight, 55% incorporated aerobic activity into their daily lifestyle, and only 5% smoked. Younger age, longer length of residence, and a bicultural or more American identity were associated with greater participation in physical activity. Higher income, a bicultural or more American ethnic identity, and depression were associated with higher fat intake. A multitude of factors influenced the practice of healthy behaviors and perceived health of Asian Indian immigrants, and needed to be taken into account when developing culturally appropriate health promotion interventions. One study of refugees’ knowledge and perceptions of nutrition, physical activity, and smoking behaviors indicated that they had a realistic perception of their weight (55% felt they were overweight), and none thought obesity was a positive characteristic.35 For all categories discussed, refugees were in the pre-contemplative stage of change. Health behaviors were expected to change over time after arrival. For Korean immigrant women to the US, needs for and attitudes toward physical activity were influenced by cultural context and immigration, and strongly associated with their daily experiences.36

Obesity in immigrants

Throughout the world, there are now more people who are overweight (1 billion) versus those who are underweight (850 million).37 The WHO standard classification for obesity in adults, and its relationship to co-morbidities, is as shown in Table 42.4.

Table 42.4 WHO standard classification of obesity (1997)

| BMI | Risk of comorbidities | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal BMI* | 18.5–24.9 | Average |

| Overweight | ||

| Pre-obese | 25.0–29.9 | Increased |

| Obesity class I | 30.0–34.9 | Moderate |

| Obesity class II | 35.0–39.9 | Severe |

| Obesity class III | >40 | Very severe |

* Body mass index (BMI) is defined as the individual’s body weight divided by the square of their height.

As the worldwide move from rural life to urban environments continues, chronic health problems worsen. For thousands of years, Israeli Bedouins lived in the desert, traveled by foot, hauled water from wells, and ate what they could raise.38 As they moved to cities, the prevalence of high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes increased, and 70% of Bedouins in Israel are now overweight or obese.

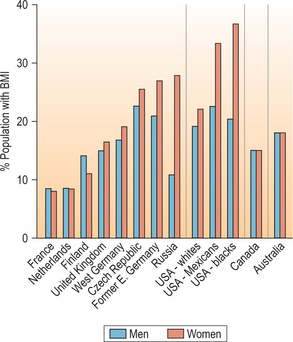

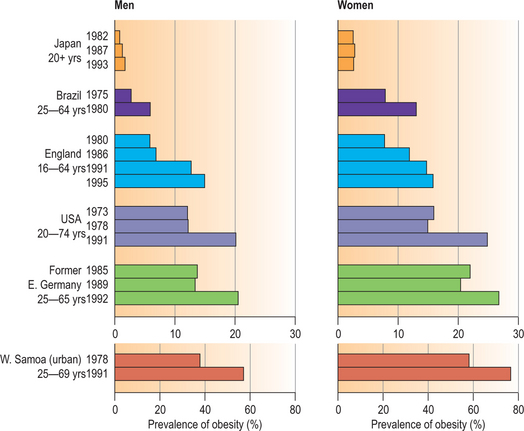

Obesity is worsening in women and men, and is not limited to industrialized countries. In the past 20 years, the rates of obesity have tripled in developing countries that have been adopting a lifestyle involving decreased physical activity and overconsumption of cheap, energy-dense food.109 The highest prevalence is in the Pacific Islands, where on the island of Nauru, for example, noted 79% of adults were obese (body mass index [BMI] >30) in 1994.39 Prentice et al. in this same study noted the lowest rates worldwide are in less-developed Asian countries, with rates elsewhere varying from 3% in Ghana, 10% in Iran, 15% in Canada, 21% in South Africa, 28% in the United States, and 29% in Bahrain (Figs 42.4, 42.5).

Nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases exacerbated by obesity include type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and selected cancers including endometrial, breast, and colon cancer.40

In a cross-sectional national study, prevalence of obesity was 16% among immigrants and 22% among US-born individuals.41 The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of obesity was 8% among immigrants living in the United States for less than 1 year, but 19% among those living in the United States for at least 15 years. The prevalence of obesity among immigrants living in the United States for at least 15 years approached that of US-born adults, with the exception of foreign-born blacks. Early intervention with information about diet and physical activity was thought to represent an opportunity to prevent weight gain, obesity, and obesity-related chronic illness. A Seattle, Washington, study on dietary acculturation noted that immigration to the US was usually accompanied by environmental and lifestyle changes that can markedly increase chronic disease risk, particularly adopting dietary patterns that tend to be high in fat and low in fruits and vegetables. Dietary acculturation was found to be multidimensional, dynamic, and complex, and varied considerably based on personal, cultural, and environmental attributes. The authors recommended that practitioners working with immigrants should determine the degree to which dietary counseling should be focused on maintaining traditional eating habits, adopting the healthful aspects of eating in Western countries, or both.42

A 2005 Canadian study demonstrated that, on average, immigrants are substantially less likely to be obese or overweight upon arrival in Canada.43 Rates of obesity and overweight converged slowly to native-born levels, but there was marked variation by the ethnicity of the immigrant. The authors found evidence that ethnic group social network effects exerted a quantitatively important influence on the incidence of being overweight and obese for members of most ethnic minorities, tempering the process of adjustment to Canadian lifestyle norms that may be driving excess weight gain with additional years in Canada.

Perceptions of body image

In many of the world’s less-developed countries, being overweight or obese was associated in the past with wealth and better health as outlined in one report from the WHO in Samoa, where obesity is epidemic (Table 42.5).

Table 42.5 Samoan perceptions of ‘big’

| Pacific idea | Western idea |

|---|---|

Source: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific Report on Workshop on Obesity Prevention and Control Strategies in the Pacific, Apia, Samoa, September 2000.

Hispanics in the United States and sub-Saharan Africans have for centuries considered overweight and obesity to be a sign of success, wealth, and good health.44 As outlined by Renzaho,44 the cultural exposure of sub-Saharan Africans to the suffering of HIV, war, natural disasters, and high levels of malnutrition, has been demonstrated to affect cultural perceptions of body image. These cultural preferences for larger body sizes prevalent in people from developing countries were also reported in white people from developed countries at the turn of twentieth century. Unlike the developed world, which has shifted from preferring larger to lean body size, sub-Saharan Africans have maintained their preference for larger body size even after migration to developed countries, regardless of the length of stay in their host country.45

However, the dangers of generalizing are again emphasized, as more recent studies indicate that as standards of living improve and obesity worsens, many societies recognize the health dangers of obesity. In a 1996 study, both male and female Polynesians from the Cook Islands preferred to be smaller.46 For Senegalese women, being overweight was the most desirable body size, however obesity was associated with greediness and the development of diabetes and heart disease.47 In a study of British Bangladeshis with diabetes, patients saw obesity as unattractive, unhealthy, and linked to diabetes and heart disease.48 Erroneous stereotypes regarding patients’ perceptions should be abandoned in favor of culturally competent nutritional outreach and education programs.

Recommended approaches

Recommendations for how to best promote healthy eating in immigrant women were outlined in a Toronto, Canada, literature review, and included the need to consider the social context of immigrant women’s experience, address cultural, linguistic, economic, and informational barriers, and consider how these change over time.49 Another New Zealand study looked at Islamic women’s barriers to fitness and exercise, and suggested innovative solutions to facilitate Somali women’s access to fitness and exercise opportunities, including exercise classes in a community center used by the Somali community, and trial memberships at a women-only fitness center.50 Many immigrants become more aware of the need for increased physical activity after adopting sedentary lifestyles after immigration. A study of married Mexican immigrant women revealed that the majority (78%) were not involved in regular physical activity and had, on average, poor cardiovascular fitness (76%).51 However, 93% had a positive attitude towards exercise, were well informed of the benefits, and perceived physical activity to be a health-promoting behavior. Cultural values and beliefs about physical activity, gender roles, and social and physiologic factors were described as barriers to women’s intention to engage in physical activity.

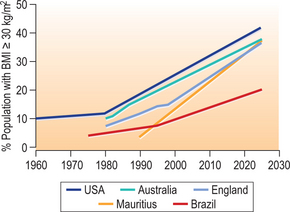

Lastly, the projected trends for obesity prevalence worldwide underscore the importance of concentrated efforts to stem the epidemic (Fig. 42.6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree