Introduction

Preventive geriatrics is not an oxymoron. It is, however, a challenging area of medicine for many reasons. (1) How can guidelines for prevention take into account the variability seen among older persons? (2) How can preventive geriatrics balance the dichotomy between the treatment of populations and the treatment of the individual? (3) How can clinicians handle the unclear areas or ‘grey zones’ of preventive geriatrics? (4) Does early detection or case finding equate with better outcomes?

To deal with these questions, this chapter presents a model of preventive geriatrics called the Health Maintenance Clinical Glidepath, which is primarily for office-based practices. It addresses screening for geriatric specific areas (e.g. cognition, gait and balance) and also screening for common medical illnesses and diseases (e.g. certain cancers, heart disease).

Background

Prevention in medicine has traditionally been divided into primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. Primary prevention is the prevention of disease before it actually starts.

The traditional definition of secondary prevention is the detection of disease at an early stage. This can be detection of asymptomatic disease by screening tests or identification of unreported problems by case finding. The following caution needs to be added to the definition. Detection should only be done if detection is likely to improve outcomes such as mortality, morbidity, function or quality of life. The priority and importance of outcomes need to be made based on patient preference.

Tertiary screening, using a comprehensive geriatric assessment approach, allows for identification and intervention of established health conditions such as cognitive impairment, gait and balance disorders, malnutrition and urinary incontinence. The goal of the intervention would be to prevent or minimize a patient’s functional decline in order to maintain their independent lifestyle, since functional decline and loss of independence are not inevitable consequences of ageing.

The Health Maintenance Clinical Glidepath

The Health Maintenance Clinical Glidepath answers the first two questions above and addresses the limitations of two types of clinical decision-making tools: practice guidelines and evidence-based medicine (EBM). Although practice guidelines and EBM have been important in raising the standards of healthcare in the past decade, their use in preventive geriatrics is limited. Many guidelines do not include older age groups and, if they do, they are no more specific than ‘over 65 years of age’. EBM emphasizes outcomes of populations, whereas clinical practice emphasizes the outcome of the individual. One of the limitations of EBM is the discrepancy between patients in the EBM studies and in clinical practice. For example, many randomized controlled trials of medication interventions for common diseases such as congestive heart failure and osteoporosis exclude patients who are frail, demented or at the end of life.

The older we get, the more unique we become. Chronological age does not equate with physiological or functional age. Guidelines for preventive geriatrics need to take this into account. One approach is to use life expectancy and functional status to help delineate categories of older persons that are more useful than those based on chronological age. Overall health status is a good predictor of life expectancy compared with age alone and functional capacity among older persons has been found to be a predictor of mortality. Four categories can be used to help guide decisions about preventive measures. Although overlap exists and functional status may fluctuate, Gillick proposed the following: Robust (life expectancy of >5 years and functionally independent); Frail (life expectancy of <5e years and significant functional impairment); Moderately Demented (life expectancy 2–10 years and may or may not be functionally impaired); and End of Life (usually a life expectancy of <2 years).1

Preventive geriatrics requires making decisions. Healthcare decisions are complex, involving society, healthcare workers and patients. Guidelines for preventive geriatrics need to take into account the following practice principles: (1) patients’ expectations and needs, including quality of life, satisfaction and reassurance; (2) physicians’ need for diagnostic certainty; (3) physicians’ comfort with risk taking and concerns about malpractice; (4) the need for cost-effective medical care; (5) variations in practice patterns, particularly with regard to subspecialty care; and (6) the practical realities of running a practice.2

Healthcare decisions are not black and white. Thus, four levels of recommendation were developed to allow for decisions to be made on a ‘graded’ rather than an ‘all or nothing’ basis and to allow for better patient involvement in decision-making. The four levels are also based, when available, on the strength or weakness of EBM that exists or does not exist. The four levels are ‘Do’, ‘Discuss’, ‘Consider’ and ‘* * * *’. ‘Do’ reflects the strongest recommendation. ‘Discuss’ reflects a recommendation that the physician discusses the risk–benefit of the decision with the patient. ‘Consider’ reflects a recommendation that the physician gives consideration, but does not necessarily need to discuss the decision with the patient. ‘* * * *’ reflects that a particular evaluation or management measure is not recommended, based on these principles.

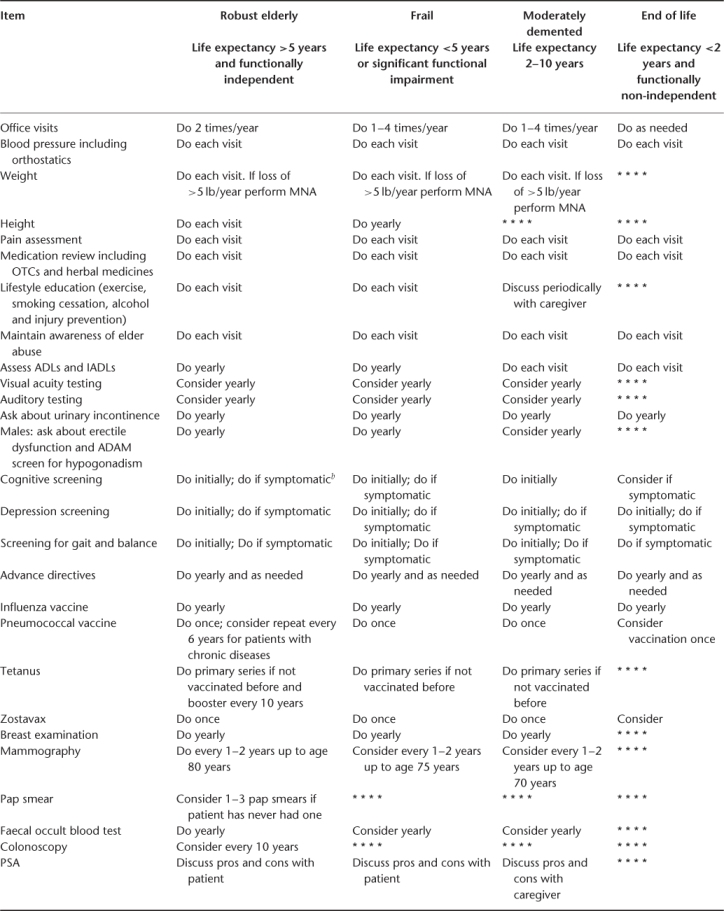

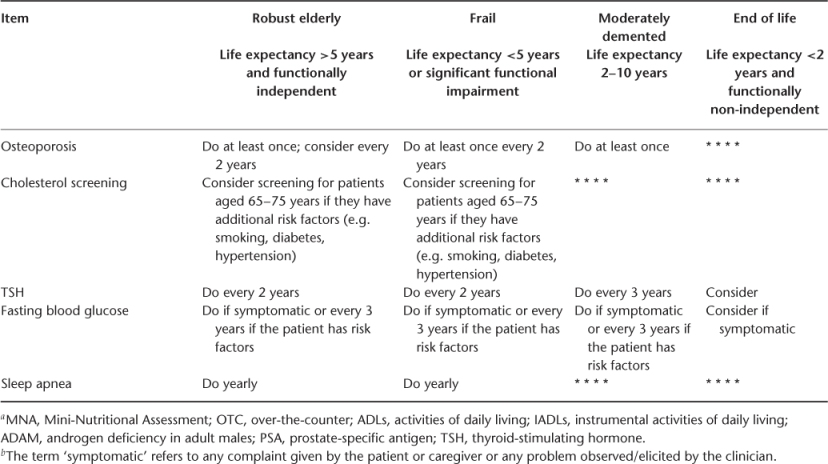

Table 12.1 is a shortened version of the original Health Maintenance Clinical Glidepath which details the recommendations for each area of prevention and for each category of Robust, Frail, Moderately Demented and End of Life. It will be noted in the following sections whether recommendations are based on organizational guidelines, EBM or expert consensus. All areas of the Glidepath underwent a Delphi process.3

Table 12.1 The Health Maintenance Clinical Glidepatha.

Office Visits

Although there is no direct evidence available on how often Robust elderly versus Frail or Moderately Demented elderly need office visits, because other screening procedures need to be done, the minimum frequency should be once per year. ‘Do as needed’ is recommended for elderly at the End of Life because of potential limitations or inability on the part of the patient to get to the office.

Blood Pressure (BP) Including Orthostatic Measurements

Performing BP measurements in all groups is recommended at each visit. Although this pertains to screening for hypertension in all four categories, it also pertains to hypotension (and associated symptoms) in the Frail, Moderately Demented and End of Life categories. Recommendations for hypertension screening are based on organizational guidelines. Although most organizations agree on the importance of screening for hypertension, they do not agree on how often. For example, the recommendations of the American College of Physicians (ACP) for BP screening for adults range from every 1–2 years to every 2–5 years for normotensive patients. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee for Hypertension (JNC 7) and The United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF)4 recommend BP screening for normotensive patients every 1–2 years and yearly for prehypertensive patients.5 Note that these organizations do not take into account extreme ages of the elderly (for example, the difference between an 85-year-old and a 65-year-old person). They also set the upper limits of normal fairly low compared with more geriatric-oriented groups. The Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) Project recommends screening for systolic hypertension begin at a BP >160 mmHg.

Screening for orthostatic hypotension (OH) is based on evidence that OH is prevalent among older patients (13–30%) and that there is an association between OH and adverse outcomes. JNC 7 recommends screening all patients treated for hypertension for orthostatic hypotension, but the frequency is not specified.

Although no studies have been carried out to show improved outcomes if this screening is done, the cost and risk of the intervention are low enough that postural blood pressure measurements are recommended.

Weight

Weight loss in older patients is associated with increased mortality, morbidity and other unfavourable outcomes (e.g. loss of muscle mass, decreased muscle strength, altered immune function, decreased wound healing). The data on the benefit and outcome of nutrition management are somewhat controversial, but mostly positive. Oral nutritional supplement was shown to improve weight in nursing-home elderly, supplementation was shown to improve weight and reduce falls in frail elderly living in the community and dietary supplementation led to moderate weight gain and improvements in general well-being in homebound elderly.6–8 A meta-analysis concluded that oral nutritional supplements can improve nutritional status and seem to reduce mortality and complications for undernourished elderly patients in the hospital. Current evidence does not support routine supplementation for older people at home or for well -nourished older persons in any setting.9

Since screening for weight loss is very low cost and low risk and the benefits of intervention are mostly positive, it should be done for patients in all categories except End of Life. Outpatient screening of unintentional weight loss of 10% or greater in 1 year is indicative of significant malnutrition. Utilizing a validated screening tool, such as the Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA), can identify patients who are malnourished or at risk for malnutrition.10

Height

Since measuring height is a low-cost screening intervention and as bone loss occurs height may decrease, it may be an effective and economical method to identify early osteoporosis of the spine for Robust and Frail elderly. One study showed a significant association with historical height loss of 1.5 cm and vertebral fractures.11

Pain

Pain should now be considered the fifth vital sign and should be assessed at every visit for patients in all categories. Use of Likert scales (e.g. 1–10) or pictorial scale (e.g. facial expressions) can be useful to quantify pain. Even patients with dementia can be evaluated for pain, using such tools as the CNA Pain Assessment Tool (CPAT) and the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD-G).12, 13

Medication Review Including Over-The-Counter (OTC) and Herbal Medicines

The risk of adverse drug events, poor compliance and drug–drug interactions, and even the risk of hospitalization, are most associated with number of drugs, while underlying comorbidities and to some extent age contribute to this risk.14, 15 Patients should maintain an up-to-date medication list including OTC and herbal preparations, to bring in at each office visit or hospitalization. Medication reviews should be performed for patients in all four categories at each office visit, to assess for duplication, drug–drug or drug–disease interactions, adherence, affordability and side effects.

Lifestyle Education

Recommendations about areas of lifestyle education in general apply mainly to the Robust and Frail elderly, with a lower level of recommendation for the Moderately Demented elderly. Activity level should be queried because a low level of activity is a significant predictor of mortality among older adults.16 In robust elderly, physical activity plays an important role in prevention and reduction of mortality and treatment of various chronic and disabling conditions (e.g. obesity, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, depression, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, cognitive decline). Frail elderly undergoing randomized trials of exercise experienced fewer falls, injuries and healthcare utilization. Although the USPSTF does not recommend behavioural counselling of elderly patients by primary care physicians to promote increased physical activity, other professional organizations, such as the ACP, American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) do support exercise promotion in the elderly. Specific recommended exercises fall into four categories: aerobic, muscle strengthening, flexibility activities and balance training.

Physicians should ask patients about smoking and should clearly and directly advise all smokers to quit. Patients who want to quit should be assisted with self-help materials, encouraged to set a quit date, be referred for behavioural therapy or be advised to try OTC or prescription medications.

Alcohol abuse can initially be screened for by asking what quantity a patient consumes on a regular basis. Men who consume more than four drinks per day and women who consume more than two drinks per day are at risk of alcohol-related problems.17 A more thorough assessment should include screening tools such as the CAGE questionnaire, MAST or AUDIT. Of these three, the CAGE questionnaire has the best sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing alcohol dependence.18 Both the USPSTF and the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) recommend that primary care providers screen their older patents for alcohol misuse.

Areas of education for injury prevention include the use car seat belts, alcohol-related risks in relation to driving, home environmental hazards to reduce falls and the restriction of access to firearms and driving with depressed and cognitively impaired patients.5

Maintain Awareness of Elder Abuse

Physicians and other healthcare professionals should maintain awareness at all times for patients in all categories. A review of elder abuse screening and assessment instruments have shown that older adults were unlikely to report episodes of elder mistreatment and identification of 70% or more of elder mistreatment comes from third-party observers.19 Healthcare providers should consider referral to a social service agency for evaluation of mistreatment if elderly patients present with unexplained contusions, burns, bite marks, genital or rectal trauma, pressure ulcers and a BMI of less than 17.5%.

The term ‘awareness’ is used because no particular standardized evaluation tool for elder abuse has been shown to be better than others.20

Assess ADLs and IADLs

Prevention of functional decline is one of the hallmarks of geriatric care. Loss of function among older persons is associated with long-term care placement, morbidity and mortality. Thus, although there is no direct evidence on how often to screen older patients in each of the four categories for functional change, given the importance of this health parameter it is recommended for patients in all categories at the intervals as noted in Table 12.1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree