Which provider (gynecologic oncologist, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, other specialist, or the primary care provider) will be responsible for each aspect of the patient’s care, including posttreatment cancer surveillance, management of treatment-related adverse effects, pain management, management of non-cancerrelated medical problems, and routine cancer screening (e.g., screening for breast and colorectal cancer)?

What will be the frequency of surveillance visits and why?

What methods will be used for cancer surveillance?

When should the patient expect lingering treatmentrelated symptoms to resolve?

What symptoms should cause the patient to contact her provider before scheduled visits?

Assuming the patient does not develop recurrence or adverse effects that require special interventions, how long will she require monitoring by an oncologist, and how much of her cancer surveillance can be shared with her primary care provider?

TABLE 9.1 Potential Survivorship Quality of Care Measures (2006) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

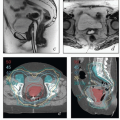

Central recurrence after initial definitive surgical treatment. Radiation therapy (RT) or chemoradiation is the usual treatment for isolated central recurrence after definitive surgery unless definitive surgical resection can be accomplished without major organ compromise (CS 12.3, 13.8, 13.9).

Regional nodal recurrence after initial definitive surgical treatment. Isolated nodal recurrences are usually treated with chemoradiation (CS 12.10, 13.6, 13.7).

Nodal recurrence near the margin of RT fields. Depending on the size of the recurrence and its relationship with previous RT fields, marginal nodal recurrences after RT may be treated with RT or surgical resection followed by RT (CS 13.5, 15.3).

Isolated central uterine, cervical, vaginal, or vulvar recurrence near the margin of RT fields (CS 10.8, 12.9). Depending on the size and extent of the recurrence and its relationship with previous RT fields, isolated central recurrences after RT may be treated with radical surgery, radiation, or palliative chemotherapy.

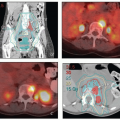

Oligometastasis. Because most patients with distant metastases are incurable, the focus of their treatment is usually palliative (Chapter 16). However, in rare cases, isolated metastases in surgical scars, lungs, or other sites may be amenable to definitive targeted treatments (CS 13.9).

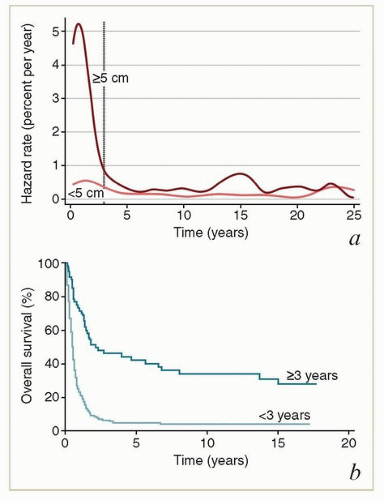

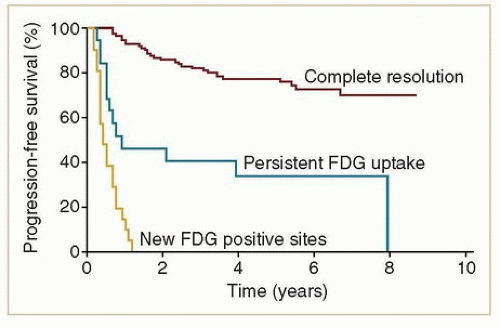

of the recurrences occurring more than 3 years after treatment undoubtedly reflected the development of new HPV-related cancers. These late recurrences were the ones most likely to be treated successfully with surgery (usually pelvic exenteration) (Fig. 9.1b). These data suggest that patients who have been cured of locally advanced cervical cancer continue to have a greater risk of developing new preinvasive and invasive cancers of the lower genital tract than does the general population.

and reflect the need for closer surveillance during the initial posttreatment period, when the risk of recurrence is highest (Table 9.2).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

recommendations vague, although they agree that routine imaging of every gynecologic cancer patient is inappropriate (Table 9.2).14,15,16

symptoms do not begin until many years later, when patients are no longer routinely followed by oncologic specialists. For this reason, it is important to use the first several years of more intensive surveillance to educate patients about the possible late adverse effects of RT and to encourage them to seek specialized care if symptoms develop.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree