Pneumonia: Introduction

Pneumonia is a common, expensive (in 2002, the total cost was $8 billion to treat pneumonia in the United States), and often serious infection with considerable morbidity and mortality. The major burden of pneumonia in a community is borne by the elderly. Successful management of pneumonia, in any patient, but especially in the elderly requires considerable skills.

Definitions

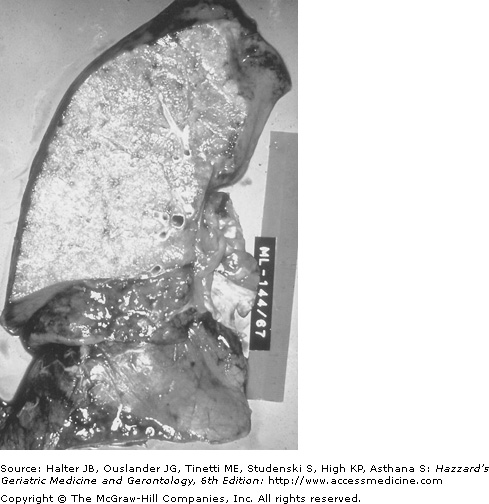

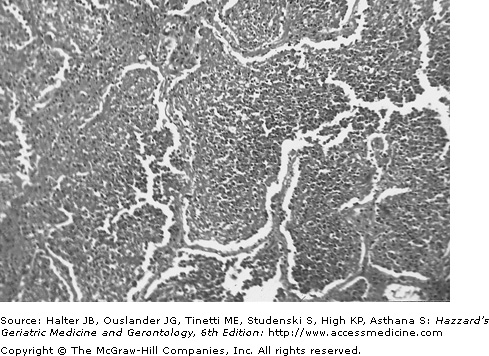

From the viewpoint of the pathologist, pneumonia is an inflammatory response in the lung caused by an infectious agent that involves the alveoli and terminal bronchioles. It is manifested by increased weight of the lungs, replacement of the normal lung sponginess by consolidation and alveoli filled with white blood cells, red blood cells, and fibrin (Figures 126-1 and 126-2).

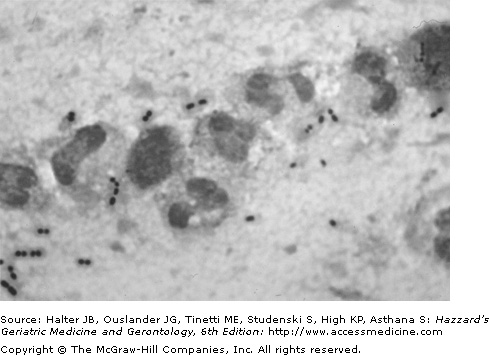

The clinician defines pneumonia as a combination of symptoms (fever, chills, cough, pleuritic chest pain, sputum), signs (hyper or hypothermia, increased respiratory rate, dullness to percussion, bronchial breathing, aegophony, crackles, wheezes, pleural friction rub), and an opacity (opacities) on a chest radiograph (Figure 126-3). In addition, laboratory findings; such as, increased white blood cell count and decreased level of oxygen saturation, may also be part of the definition.

The epidemiologist or clinical trialist defines pneumonia as two or more of the symptoms listed above, one or more of the physical findings listed above and a new opacity on chest radiograph that is not because of a condition other than pneumonia (such as, congestive heart failure, vasculitis, pulmonary infarction, atelectasis, or drug reaction).

Pneumonia may also be categorized according to the site of acquisition—community, hospital (nosocomial) or nursing home. Some authorities categorize nursing home acquired pneumonia as community-acquired, while others insist it more closely resembles nosocomial pneumonia and should be labeled institutionally acquired pneumonia. However, nursing homes or long-term care facilities have residents who range from fully functional to those who are bedridden. We prefer to consider nursing home/long-term care facility acquired pneumonia as a separate category.

It is useful for the practicing clinician to remember definitions for the certainty with which an agent can be implicated as the cause of the pneumonia. An agent is said to be the definite cause of pneumonia if it is isolated from blood (although some blood isolates, such as coagulase negative staphylococci, are usually contaminants and not pulmonary pathogens), from pleural fluid or from pulmonary tissue; if it isolated from sputum and is a pathogen that does not colonize the upper airway (such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Legionella spp.; Nocardia spp.); or if a microbial antigen is detected in urine (Streptococcus pneumoniae; Legionella pneumophila). Amplification of DNA or RNA of a microbial agent from pulmonary tissue or from nasopharyngeal secretions if that agent does not colonized the upper airway would allow categorization of the agent as the definite cause of the pneumonia. An agent is the presumptive or probable cause of pneumonia if it is isolated from a sputum sample which has >25 polymorphonuclear leucocytes per low power field and <10 squamous epithelial cells or if there is a fourfold or greater rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent serum samples. Amplification of DNA or RNA of a viral agent from nasopharyngeal secretions would qualify that agent for status as a possible cause of the pneumonia.

Epidemiology

Data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey in the United States indicate that between 1990 and 2002 there were 21.4 million hospitalizations among those 65 years of age and older. Infectious diseases accounted for 48% of these hospitalizations and 46% of the infectious diseases hospitalizations were caused by the lower respiratory tract infections. Death resulting from these infections was reported to be 48%. There has been a 20% increase in pneumonia as a first or any listed diagnosis in those 65 years of age and older from 1988 compared to 2002. The in-hospital mortality rate was 1.5 times higher for pneumonia compared with the other most common causes of hospitalization.

Pneumonia and influenza are listed as the 6th leading cause of death, and approximately 70% of hospitalized cases of pneumonia among adults occur in the elderly. Annual hospitalization rates for pneumonia and influenza were 23.1 per 1000 men aged 75 to 84 years of age and 13.3 per 1000 women in this age group. The corresponding numbers for men and women, respectively, in the 65 to 74 age group were 8.3 and 5.8 per 1000. Approximately 60% of the episodes of pneumonia among those 65 years of age and older are treated in the community. The admission rate for pneumonia is subject to considerable variation from region to region within a province or state and even from hospital to hospital within a single city. This variation cannot be explained solely on the basis of severity of illness and likely reflects variation in physician practice.

In a population-based study the following were identified as independent risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia: alcoholism, relative risk (RR) 9; asthma, RR 4.2; immunosuppression, RR 1.9; and age, RR 1.5 for those >70 years of age (vs. 60–69 years of age).

The overall mortality rate for patients with community acquired pneumonia (CAP) who require admission to hospital ranges from 6% to 15%. For those who require admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) for treatment of pneumonia, the mortality rate ranges from 45% to 57%. The annual per capita cost of pneumonia from an employer perspective is five times higher than the costs for typical beneficiaries. For elderly patients there is a burden of care for family members.

In an effort to determine the risk factors for pneumonia, investigators studied 101 patients aged ≥65 years old who were admitted with CAP, each patient with pneumonia was age and sex matched with a control subject who arrived at emergency within ±2 days of the case and was subsequently admitted. By multivariate analysis, the following were identified as risk factors for pneumonia—suspected aspiration, low serum albumin, swallowing disorder, and poor quality of life. Significant predictors of a fatal outcome were bedridden state prior to onset of pneumonia; temperature ≤37°C; presence of a swallowing disorder; respiratory rate ≥30 breaths/minute; shock; creatinine greater than 1.4 mg/dL and ≥3 lobes involved on chest radiograph.

The attack rate for pneumonia in adults is highest among those residing in nursing homes with rates of 1.2 episodes of pneumonia per 1000 resident days. Pneumonia is the leading reason for transfer of nursing home patients to hospital. In many areas, nursing home/long-term care facility acquired pneumonia accounts for 10% to 18% of all pneumonia admissions. Lower respiratory tract infections are the fourth most common infection among residents of long term care facility (LTCFs) affecting 2.1% of the residents. In a nursing home population, old age, odds ratio (OR) 1.7; male sex OR 1.9; swallowing difficulty, OR 2; and inability to take oral medication were significant risk factors for pneumonia. In another study, profound disability (Karnofsky score of <10), bedfast state, urinary incontinence, presence of a feeding tube, or deteriorating health status were risk factors for pneumonia in this setting.

For specific etiologies of pneumonia, risk factors may differ from those for pneumonia as a whole. Thus, dementia, seizures, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, tobacco smoking, and chronic obstructive lung disease are risk factors for pneumococcal pneumonia. Fifty percent of patients with bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia were homozygous for FcγRIIa-R31, which binds weakly to IgG2, compared with 29% of uninfected controls suggesting that genetic factors may also be important risk factors for pneumococcal pneumonia.

Among HIV-infected patients the rate of pneumococcal pneumonia is up to 41.8 times higher than age matched patients who are not HIV-infected. Risk factors for Legionnaires’ disease (LD) include male gender, tobacco smoking, diabetes, hematologic malignancy, cancer, end stage renal disease and HIV infection.

In a large study of 3474 adults hospitalized for the treatment of CAP, the mean length of stay (LOS) was 8.6±6.3 days and the median LOS was 6.4 days. Patients were divided into those who stayed <7 days versus those who stayed >7 days and factors associated with these LOS were examined by multivariate analysis. Older age, ex-smoker status, home care prior to admission, reduced pre-morbid functional status and longer time to first dose of antibiotic were all associated with a longer stay. In contrast male gender, pathway use (refers to use of a critical pathway for treating CAP), residence at home without home care and shorter time to receipt of first dose of antibiotic were associated with a shorter stay. LOS was also independently associated with the hospital to which the patient was admitted. Thus, there are patient, institution, and physician factors that influence LOS in elderly patients with CAP.

Etiology

There are more than 100 microbial (bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and other parasites) causes of community-acquired pneumonia. S. pneumoniae is the most common cause of CAP accounting for approximately 50% of all cases. Advances in technology such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction are changing our knowledge of the etiology of pneumonia. It is apparent that viral pneumonia is more common in adults than was previously thought and in many instances a viral upper respiratory tract infection impairs ciliary clearance and pneumonia results from microaspiration of oropharyngeal microflora. Table 126-1 gives the most common causes of CAP. Table 126-2 identifies clues that might be obtained from the history to suggest a particular organism(s) as the cause of the pneumonia. It is important to remember that the relative frequency of each pathogen may vary geographically and seasonally. Many elderly persons travel for pleasure, placing them at risk for a variety of pathogens (Table 126-2). Vacations in the sun to Arizona or parts of California can result in acquisition of the fungus Coccidioides immitis by inhalation. In most instances, the infection is asymptomatic. However, atypical pneumonia, hilar adenopathy or lung nodules may result. The latter are often misdiagnosed as carcinoma and the nodules excised. Elderly women who are receiving hormone replacement therapy may be at greater risk for the pulmonary nodule presentation of coccidioidomycosis. Legionellosis is also associated with travel.

|

FACTOR | POSSIBLE AGENT(S) |

|---|---|

Travel | |

Southeast Asia | Burkholderia pseudomallei (melioidosis); M.tuberculosis |

Many countries | M. tuberculosis |

Arizona, parts of California | C. immitis |

Occupational History | |

Health care workers | M. tuberculosis, acute HIV seroconversion with pneumonia (if recent needlestick injury from an HIV positive patient) |

Veterinarian, farmer, abattoir worker | C. burnetii |

Host Factor | |

Diabetic ketoacidosis | S. pneumoniae, S. aureus |

Alcoholism | S. pneumoniae, Kelbsiella pneumoniae, S. aureus, oral anaerobes; Acinetobacter spp. |

Chronic obstructive lung disease | S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis |

Solid organ transplant recipient | S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, Legionella spp., P. jiroveci, (pneumonia occuring >3 mo cytomegalovirus, Strongyloides stercoralis after transplant) |

Sickle cell disease | S. pneumoniae |

HIV infection and CD4 cell count of <200/μL | S. pneumoniae, P. jirovecii, H. influenzae, Cryptococcus neoformans, M. tuberculosis, Rhodococcus equi |

Dementia, stroke, altered level of consciousness | Aspiration pneumonitis |

Structural lung disease (bronchiectasis) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Environmental Factors | |

Exposure to: contaminated air conditioning, cooling towers, hot tub, recent travel stay in a hotel, exposure to grocery store mist machine, or visit to, or recent stay in a hospital with contaminated (by Legionellaceae) drinking water | L. pneumophila or other Legionellaceae |

Exposure to: mouse droppings in an endemic area | Hantavirus |

Pneumonia after windstorm in an area | C. immitis of endemicity |

Outbreak of pneumonia in shelter for homeless men or jail | S. pneumoniae, M. tuberculosis |

Outbreak of pneumonia occurs in military training camp | S. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae, Adenovirus |

Outbreak of pneumonia in a nursing home | C. pneumoniae, S. pneumoniae, Respiratory syncytial virus, Influenza A virus; M. tuberculosis |

Pneumonia associated with mowing a lawn in an endemic area | Francisella tularensis |

Exposure to bats, excavation or residence in an endemic area (Ohio and Mississippi river valleys) | Histoplasma capsulatum |

Exposure to parturient cats in an endemic area | C. burnetii |

Sleeping in a rose garden | Sporothrix shenkii |

Camping, cutting down trees in an endemic area | Blastomyces dermatiditis |

Worldwide S. pneumoniae continues to be the most common cause of CAP. It accounts for approximately 50% of all cases of pneumonia requiring admission to hospital for treatment and for 60% of all cases of bacteremic pneumonia. While there are more than 90 capsular polysaccharide types of S. pneumoniae, 80% of the strains that cause invasive disease are present in the 23-valent-pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. These include serotypses 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19A, 19F, 20, 22F, 23F, 33F. Vaccination of children with a 7-valent protein conjugate vaccine (contains serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, 23F) has resulted in a decrease in invasive pneumococcal disease not only in children but also in elderly persons as well. Recently there has been emergence of outbreaks of invasive pneumococcal disease caused by serotype 5 among homeless adults.

One of the problems facing clinicians treating patients with CAP is drug-resistant S. pneumoniae. If an isolate is resistant to penicillin, it is likely also that it is resistant to three or more drug classes (multidrug resistant). Currently, 12% to 25% of S. pneumoniae isolates in North America are resistant to penicillin—approximately half demonstrate low-level resistance (minimal inhibitory concentration 0.1–1.0 mg/L) and half have high-level resistance (MIC ≥ 2 mg/L). In many communities, the levels of penicillin resistance are much higher than this. In the United States and Canada, approximately 20% of isolates of S. pneumoniae are resistant to erythromycin and the other macrolides. This resistance may be because of an efflux pump mechanism or to alteration of the target site of erythromycin action through a mutation in the erm gene. Approximately 70% of pneumococal erythromycin resistance in North America is as a result of an efflux pump mechanism and these isolates may respond to treatment with a macrolide. Isolates that are resistant as a result of the target site modification will not respond to treatment with a macrolide. Risk factors for penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae (PRSP) include β-lactam antibiotic use within the previous 6 months; residence in a nursing home; residence in a day care center or being a parent of a resident in a day care center; and immunocompromised state. Age <5 years and nosocomial acquisition of the infection were independent predictions of macrolide resistance. Resistance among isolates of S. pneumoniae is also beginning to appear to fluoroquinolones, although at present it is uncommon with a 1% to 2% level of resistance. Risk factors for fluoroquinolone-resistant S. pneumoniae are presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; nursing home residence; fluoroquinolone use within the last 12 months and nosocomial acquisition of the infection. More than 30% of S.pneumoniae isolates are resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and approximately 15% are resistant to tetracycline. In general, third-generation cephalosporins can be used to treat patients with drug-resistant S. pneumoniae. If central nervous system infection complicates the pneumonia, vancomycin should be added. Cefixime, cefibuten, cefaclor, and loracarbef have poor activity against S. pneumoniae and should not be used to treat pneumonia caused by this microorganism.

Early mortality (within the first 3 or 4 days) in patients with bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia may not be influenced by antibiotic therapy. An APACHE II (the acute physiology and chronic health evaluation scoring system) score of ≥28 is associated with a mortality rate of 80% in patients with bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia.

Staphylococcus aureus is an uncommon cause of CAP, accounting for 1% to 5% of cases. However, it is approximately the third most frequent cause of bacteremic pneumonia and it is more common in patients with severe pneumonia who require treatment in an ICU. It is also more common as a cause of pneumonia among residents of long-term care facilities. S. aureus pneumonia has classically been described as a secondary bacterial pathogen in the setting of a primary influenza virus upper respiratory tract infection. In the setting of bacteremic S. aureus pneumonia one should always exclude endocarditis (often right sided), especially if there are multiple rounded opacities on the chest radiograph (septic emboli). Methicillin resistance (Methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]) among isolates of S. aureus was first reported in 1961 and is now common in both community and hospital acquired infections caused by this microorganism. Fortunately, vancomycin resistance, while it has been reported, is uncommon. More recently, community-acquired MRSA infections have been caused by strains producing the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL). In 1932, Panton and Valentine described leukocidin as a virulence factor. Production of this leucocidin is now known to be associated with tissue necrosis. In one study, hemopytsis was found in 38% of 16 patients with severe pneumonia associated with S. aureus strains carrying PVL genes compared with 1 of 33 PVL negative patients. To date PVL S. aureus infections including pneumonia have been more common in young patients.

Chlamydophila pneumoniae is commonly implicated serologically as a cause of CAP. It is more frequent in those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In the older adults, it usually manifests as reactivation of previous infection, while in younger adults it can be a primary infection. It is not necessary to include diagnostic studies for C. pneumoniae in working up a patient with CAP since in more than 50% of cases it is a copathogen and patients recover without specific treatment directed at C. pneumoniae. Outbreaks of pneumonia in nursing homes have been caused by this agent.

This microorganism is usually a cause of pneumonia in young adults; however, it can also cause pneumonia in older adults. It has rarely been responsible for outbreaks of pneumonia in nursing homes. M. pneumoniae has a number of extrapulmonary manifestations including—cold agglutinin induced hemolytic anemia; leukoerythrophagocytosis; encephalitis; cerebellar ataxia; stroke like syndromes; arthritis; erythema multiforme; and a maculopapular rash.

The most common cause of LD is L. pneumophila serogroup 1, although just under half of the more than 40 recognized species in the Legionellaceae family can cause LD. Legionella spp. often cause a severe pneumonia with a high mortality rate. Epidemiologically, there is frequently a history of exposure to a contaminated water source. Outbreaks have been associated with exposure to a variety of aerosol-producing devices, including showers, a grocery store mist machine, cooling towers, whirlpool spas, decorative fountains, and evaporative condensers. It is also likely that aspiration of contaminated potable water by immunosuppressed patients is also a mechanism whereby Legionella is acquired. Outbreaks of pneumonia caused by Legionella spp. appear to be uncommon in nursing homes (but they have occurred) and are more likely to occur in a community or hospital setting. In the United States, rates of LD are higher in northern states and during the summer. From 1980 through 1998, there was a change in the methods of diagnosing LD in the US with a decline in the number of cases diagnosed by culture and direct fluorescent antibody test and serology and an increase in the number of cases diagnosed by the detection of antigen in the urine. These trends were associated with a decrease in the mortality rate from 26% to 10% for community-acquired cases and from 46% to 14% for nosocomial cases. Severe headache combined with hyponatremia are features that should raise a clinical suspicion of LD although the clinical features are usually not distinctive. L. pneumophila serogroup 1 accounts for most cases of LD in the United States. Legionella longbeachae accounts for 72% of the cases of LD in western Australia. In this area, cases have occurred in active gardeners and the organism has been isolated from potting soil. When patients with LD are compared with those with community-acquired pneumonia caused by other agents the patients with LD are more likely to have myalgias, headache, diarrhea, and a higher mean oral temperature at the time of presentation. They also present to hospital sooner after the onset of symptoms—4.7 days versus 7.7 days (p = 0.02). When patients with LD were compared with patients with bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia the following features were associated with L. pneumonia—male sex, OR 4.6 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.48–14.5; heavy drinking 4.8 (1.39–16.42); previous β-lactam therapy 19.9 (3.47–114.2); axillary temperature >39 C 10.3 (2.71–38.84); myalgias 8.5 (2.35–30.74); gastrointestinal symptoms 3.5 (1.01–12.18). Negative associations included pleuritic chest pain, previous upper respiratory tract infection and purulent sputum.

In a study from Barcelona, 104 patients <65 years of age with LD were compared with the 54 patients who were older than 65 years of age. The older patients had more comorbidities and a greater likelihood of receiving corticosteroids while the younger patients were more likely to be male, smoke, have alcoholism and HIV. Fever, diarrhea and headache were less frequent in those older than 65 years of age. There was no difference in complications or requirement for mechanical ventilation. While the mortality rate was twice as high in the elderly, 11.2% versus 4.8%, the difference was not statistically significant.

Enterobacteriaceae are commonly isolated from the sputum of elderly patients with CAP. The problem is distinguishing colonization from infection since these microorganisms commonly colonize the upper airway of elderly persons. Elderly patients who are bacteremic (usually secondary to pyelonephritis), with Escherichia coli in particular may have secondary seeding of the lungs.

Nursing home residents account for 20% of cases of tuberculosis in older people. In the 1980s, approximately 12% of persons entering a nursing home were tuberculin positive, and active tuberculosis developed in 1% of isoniazid (INH) treated tuberculin positive patients compared with 2.4% of those who did not receive INH. The incidence of active tuberculosis among nursing home patients is 10 to 30 times greater than among community-dwelling elderly adults—thus, tuberculosis should always be considered in nursing home patients with pneumonia.

There are a large number of viruses that affect the respiratory tract (predominately the upper respiratory tract). These include influenza A and B viruses; parainfluenza viruses 1,2,3,4; adenovirus; respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumoviruses (HMPVs) A and B, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) CoV, coronaviruses, hantaviruses and varicella. Viruses are estimated to be the cause of adult CAP in 10% to 31% of cases. In a prospective study of 338 nonimmunocompromised adults with a diagnosis of CAP in whom paired serology for respiratory viruses were obtained, 61 patients (18%) had a respiratory virus identified. Influenza virus was the most common (37 patients), followed by parainfluenza (11 patients), respiratory syncytial virus (5 patients), adenovirus (5 patients), and mixed viruses (3 patients). In most instances the virus infects the upper airway, impairs ciliary function so that bacteria which are microaspirated into the LRT are not cleared and bacterial pneumonia results.