Figure 180.1 High-resolution computed tomographic image of the upper lung zones demonstrates diffuse micronodules, patchy ground-glass opacities, as well as some fine reticulation, all suggestive of an interstitial process consistent with Pneumocystis pneumonia. (Courtesy of Frederic Hellwitz, MD, Department of Radiology, Albany Medical College, Albany, NY). Reprinted with permission from Thieme Publishers.

Diagnosis

Pneumocystis has no effective culture-based test and the diagnosis, if suspected on clinical grounds, usually relies on obtaining invasive respiratory specimens. Tests on routine sputum specimens are insensitive and should not be performed, although induced sputum (performed with a respiratory therapist after inhalation of nebulized hypertonic saline) is about 50% sensitive. The sensitivity varies but approaches 90% in some institutions depending on technique proficiency and the experience of the laboratory. A negative result would not rule out PCP. Optimal testing requires bronchoscopy and bronchiolar lavage. Lung biopsy is diagnostic.

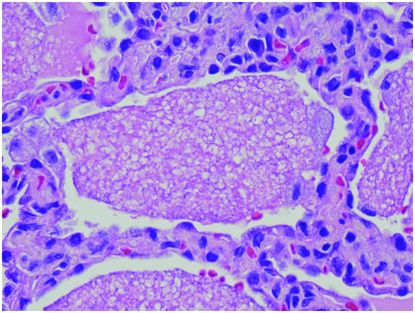

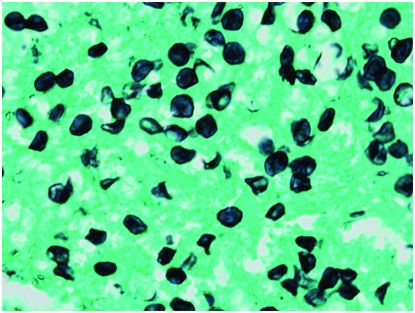

The classic histology findings are “foamy alveolar casts,” in which there is proteinaceous fluid within the alveoli (Figure 180.2). With a silver stain such as GMS, pneumocystis can be visualized as teacup-shaped organisms (Figure 180.3). Immunofluorescence techniques such as direct fluorescent antigen (DFA) can also be employed and are sensitive and specific. PCR testing is not readily available and is more difficult to interpret (carriage versus infection) due to its increased sensitivity.

Figure 180.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain of lung alveolae, showing foamy infiltrates (foamy alveolar casts). (Courtesy of Anna-Luise Katzenstein, MD, Department of Anatomic Pathology, State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY.) Reprinted with permission from Thieme Publishers.

Figure 180.3 Grocott’s methenamine silver stain of lung alveolae, highlighting the Pneumocystis organisms in black. (Courtesy of Anna-Luise Katzenstein, MD, Department of Anatomic Pathology, State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY.) Reprinted with permission from Thieme publishers.

In certain clinical settings, it may not be practical or safe to obtain invasive specimens, and noninvasive specimens are preferred. Serologic testing specific to PCP is available, but cannot reliably distinguish between past and present infection. The majority of people will, at some point, become colonized with Pneumocystis and seroconvert, although some efforts have been made towards using the specific antibody titers or responses to specific proteins as being more indicative of active infection.

The Pneumocystis cell wall contains the same 1–3 β-D-glucan (BDG) as candida and aspergillus, and an assay for serum levels of BDG (known as Fungitell commercially) has proven to be sensitive and specific for PCP, when appropriate cutoff levels are used. Because of the cross-reactivity of the assay to multiple fungi, interpretation of assay results should be done in the clinical context of the patient. PCP may be associated with somewhat higher levels of BDG than are seen in invasive candidiasis or aspergillosis. In patients with non-HIV PCP, and in children with PCP, levels tend to be higher than in HIV-associated PCP but there are no levels at which PCP can be reliably ruled in or out. In all cases, serum levels can be used to track response to treatment.

Treatment and prophylaxis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree