Clinical syndrome

Commonly associated fungi

Therapy

Onychomycosis

Onychocola, Alternaria

Itraconazole or terbinafine

Subcutaneous nodules

Exophiala, Alternaria, Phialophora

Surgery ± itraconazole or voriconazole

Keratitis

Curvularia, Bipolaris, Exserohilum, Lasiodiplodia

Topical natamycin ± itraconazole or voriconazole

Allergic fungal sinusitis/Allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis (disease)

Curvularia, Bipolaris

Corticosteroids ± itraconazole or voriconazole

Pneumonia

Ochroconis, Exophiala, Chaetomium

Itraconazole or voriconazole (amphotericin B if severe)

Brain abscess

Cladophialophora (C. bantiana), Ramichloridium (R. mackenzei), Ochroconis

See text

Disseminated disease

Scedosporium (S. prolificans), Bipolaris, Wangiella

See text

Guidelines are available for the handling of potentially infectious fungi in the laboratory setting. Cultures of certain well-known pathogenic fungi, such as Coccidioides immitis and Histoplasma capsulatum, are suggested to be worked with in a Biosafety Level 3 facility, which requires a separate negative pressure room. Recently, certain agents of phaeohyphomycosis, in particular Cladophialophora bantiana, have been included in the list of fungi that should be kept under Biosafety Level 2 containment [5]. This seems reasonable given their propensity, albeit rarely, for causing life-threatening infection in normal individuals.

Epidemiology

These fungi are typically soil organisms and generally distributed worldwide [6]. However, there are species that do appear to be geographically restricted, such as Ramichloridium mackenzei, which has only been seen in patients from the Middle East [7]. Exposure is thought to be from inhalation or minor trauma, which may not even be noticed by the patient. Anecdotal reports suggest that smoking may be a risk factor in patients who are immunodeficient [8]. Surveys of outdoor air for fungal spores routinely observe dematiaceous fungi [9]. This suggests that most if not all individuals are exposed to them, though they remain uncommon causes of disease. These fungi may also be found to be contaminants in cultures, making the determination of clinical significance problematic. At one institution, only 10 % of positive cultures were associated with clinical disease [10]. A high degree of clinical suspicion as well as correlation with appropriate clinical findings and histopathology is required when interpreting culture results.

Pathogenesis and Immunology

Little is known regarding the pathogenic mechanisms by which these fungi cause disease. One of the likely virulence factors is the presence of melanin in the cell wall, which is common to all dematiaceous fungi. It may confer a protective advantage by scavenging free radicals that are produced by phagocytic cells in their oxidative burst that normally kill most organisms [11]. In addition, melanin may bind to hydrolytic enzymes, thereby preventing their action on the plasma membrane [11]. In the yeasts Cryptococcus neoformans and Wangiella dermatitidis, disruption of melanin production leads to markedly reduced virulence in animal models [12, 13]. Melanin has also been associated with decreased susceptibility of fungi to certain antifungals, possibly by binding these drugs [14, 15]. It is interesting to note that almost all allergic diseases and eosinophilia are caused by two genera, Bipolaris and Curvularia, though the virulence factors responsible for eliciting allergic reactions are unclear at present [16].

Clinical Manifestations

Superficial Infections

Superficial infections are the most common form of disease associated with phaeohyphomycosis. These may be divided into tinea nigra, onychomycosis, subcutaneous lesions, and keratitis and are generally associated with minor trauma or other environmental exposure. Although many pathogens have been reported, relatively few are responsible for the majority of infections.

Tinea nigra is primarily seen in tropical areas, and involves only the stratum corneum of the skin. Patients are generally asymptomatic, presenting with brownish-black macular lesions, almost exclusively on the palms and soles. Hortaea werneckii is the most commonly isolated species, though Stenella araguata has also been cultured from lesions [17]. Tinea nigra may be confused with a variety of other diseases, including dysplastic nevi, melanoma, syphilis, or Addison’s disease. Diagnosis is made by scrapings of lesions and culture. As it is a very superficial infection, simple scraping or abrasion can be curative, though topical treatments such as keratolytics or imidazole creams are also highly effective [17].

Dematiaceous fungi are rare causes of onychomycosis, and the term fungal melanonychia has been used to describe this entity, which is seen predominantly in tropical regions [18]. Clinical features may include a history of trauma, the involvement of only one or two toenails, and the lack of response to standard systemic therapy [19]. Twenty-one species have been implicated as causes, including Alternaria, Curvularia, and Scytalidium have been reported, with the latter being highly resistant to therapy [18].

There are numerous case reports of subcutaneous infection due to a wide variety of species [20, 21]. Minor trauma is the usual inciting factor, though it may be unrecognized by the patient. Lesions typically occur on exposed areas of the body and often appear cystic or papular. Immunocompromised patients are at increased risk of subsequent dissemination. Occasionally, these infections may involve joints or bone.

Fungal keratitis is an important ophthalmologic problem, particularly in tropical areas of the world. In one large series, 40 % of all infectious keratitis was caused by fungi, almost exclusively molds [22]. The most common fungi are Fusarium and Aspergillus, followed by dematiaceous fungi (up to 8–17 % of cases) [23]. Approximately, half of the cases are associated with trauma; prior eye surgery, diabetes, and contact lens use have also been noted as important risk factors [23]. In a study from the USA of 43 cases of Curvularia keratitis, almost all were associated with trauma [24]. Plants were the most common source, though several cases involving metal injuries were seen as well.

Allergic Disease

Relatively few species have been associated with allergic disease. Alternaria alternata is thought to be involved in some cases of asthma [25]. Whether dematiaceous fungi may be responsible for symptoms of allergic rhinitis is unclear, as it is difficult to quantitate exposure and to distinguish them from other causes [26].

Bipolaris and Curvularia are responsible for most cases of allergic fungal sinusitis (AFS) and allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis (ABPM). Patients with AFS usually present with chronic sinus symptoms that are not responsive to antibiotics. Previously, Aspergillus was thought to be the most common fungus responsible for allergic sinusitis, but it is now appreciated that disease due to dematiaceous fungi actually comprises the majority of cases [27]. Criteria suggested for this disease include (1) nasal polyps, (2) the presence of allergic mucin, containing Charcot–Leyden crystals and eosinophils, (3) hyphal elements in the mucosa without the evidence of tissue invasion, (4) positive skin test to fungal allergens, and (5) on computed tomography (CT) scans, characteristic areas of central hyperattenuation within the sinus cavity [28]. Diagnosis generally depends on the demonstration of allergic mucin, with or without actual culture of the organism.

Allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis (ABPM) (or disease (ABPD)) is similar in presentation to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), which is typically seen in patients with asthma or cystic fibrosis [29]. Criteria for the diagnosis of ABPA in patients with asthma include: (1) asthma, (2) positive skin test for fungal allergens, (3) elevated IgE levels, (4) Aspergillus-specific IgE, and (5) proximal bronchiectasis [30]. Similar criteria for ABPM are not established, but finding allergic mucin (Charcot–Leyden crystals and eosinophils) without tissue invasion, as in AFS, makes this diagnosis highly likely [31].

Pneumonia

Nonallergic pulmonary disease is usually seen in immunocompromised patients, and may be due to a wide variety of species, in contrast to allergic disease [16, 31–34]. Clinical manifestations include pneumonia, asymptomatic solitary pulmonary nodules, and endobronchial lesions which may cause hemoptysis.

Brain Abscess

This is a rare, but frequently fatal manifestation of phaeohyphomycosis [35]. Interestingly, over half of the reported cases have occurred in patients with no risk factors or known immunodeficiency. Lesions are usually solitary. Symptoms may include headache, neurologic deficits, and seizures, though the classic triad seen in bacterial brain abscess (fever, headache, and focal neurologic deficit) is not usually present. The most commonly isolated organism is Cladophialophora bantiana, particularly in immunocompetent patients. The pathogenesis may be hematogenous spread from an initial, presumably subclinical pulmonary focus. However, other risk factors such as chronic sinusitis or smoking have been implicated in case reports [8, 36]. It remains unclear why these fungi preferentially cause central nervous disease (CNS) disease.

Disseminated Infection

This is the most uncommon manifestation of infection seen with dematiaceous fungi. Most patients are immunocompromised, though occasional patients without known immunodeficiency or risk factors have developed disseminated disease as well [37]. In contrast to most invasive mold infections, blood cultures are often positive. The most commonly isolated fungus, Scedosporium prolificans, may also be associated with septic shock. Peripheral eosinophilia, seen in 11 % of cases, is more commonly associated with Bipolaris or Curvularia.

Diagnosis

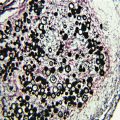

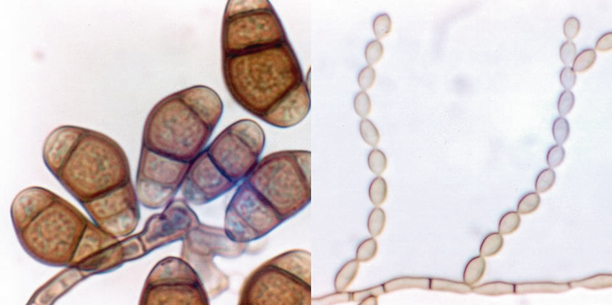

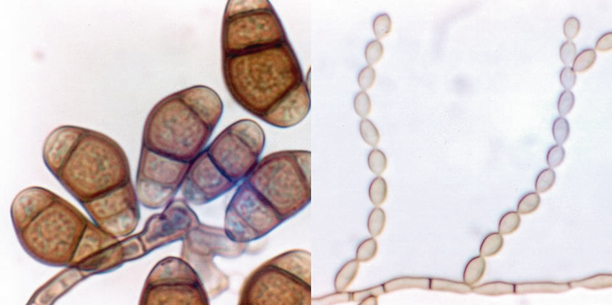

In contrast to other common mycoses that cause human disease, there are no specific serologic or antigen tests available to detect these fungi in blood or tissue. However, the nonspecific serum 1,3-β-d-glucan test may be positive in certain cases of invasive disease [38], and certain species have been demonstrated to contain the FKS gene responsible for its production [39]. The diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis currently rests on pathologic examination of clinical specimens and careful gross and microscopic examination of cultures (Fig. 12.1). Hospital laboratories can generally identify the most common genera associated with human disease (Fig. 12.2), though referral to a reference laboratory is often needed to identify unusual species. As many of these are rarely seen in practice, a high degree of clinical suspicion is required when interpreting culture results. Increasingly, molecular techniques such as internal transcribed sequence (ITS) sequencing are being used to definitively identify isolates to the species level and are becoming the standard to distinguish between closely related strains and establish novel species [4].

Fig. 12.1

Diagnostic approach for phaeohyphomycosis

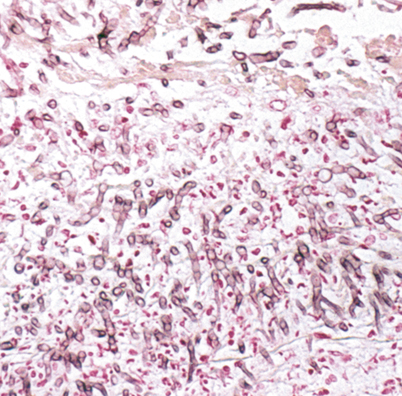

Fig. 12.2

Commonly seen fungi causing phaeohyphomycosis. Left panel, Curvularia lunata; right panel, Cladophialophora bantiana

In tissues, these fungi stain strongly with the Fontana-Masson stain, which is specific for melanin (Fig. 12.3) [3]. This can be helpful in distinguishing these fungi from other species, particularly Aspergillus. In addition, hyphae typically appear more fragmented in tissue than seen with Aspergillus, with irregular septate hyphae and beaded, yeast-like forms [3].

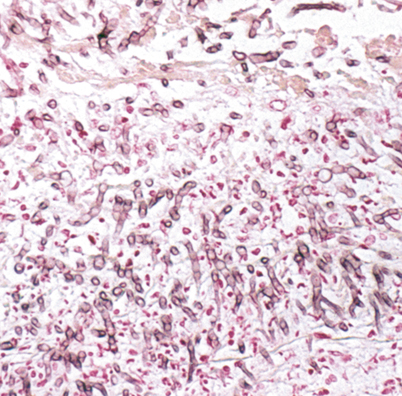

Fig. 12.3

Fontana-Masson stain of Bipolaris infection in the lung, demonstrating irregular hyphae and beaded yeast-like forms

Treatment

Therapy is not standardized for any of these clinical syndromes, and randomized trials are unlikely given the sporadic nature of cases. Itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole demonstrate the most consistent in vitro activity against this group of fungi, though far more clinical experience has accumulated with itraconazole [40]. Isavuconazole is a novel triazole with good in vitro activity, though it is not yet approved for use [41, 42]. Amphotericin B may be used for severe infections in unstable patients; high doses of lipid formulations may have a role in the treatment of refractory cases or in patients intolerant of standard amphotericin B. However, some species of dematiaceous fungi are resistant to this agent. Once the infection is under control, longer-term therapy with a broad-spectrum oral azole is often reasonable until complete response is achieved, which may require several weeks to months.

Other agents have limited roles in treating these fungi. Ketoconazole is not well tolerated, and fluconazole has poor activity against these fungi in general. Terbinafine and flucytosine have occasionally been used for subcutaneous infections in patients refractory to other therapy. Echinocandins do not appear to be very useful as single agents. Combination therapy is a potentially useful therapeutic strategy for refractory infections, particularly brain abscess and disseminated disease, though it has not been well studied. Suggested therapies for specific infections are summarized in Table 12.1.

Superficial Infections

Itraconazole and terbinafine are the most commonly used systemic agents for onychomycosis, and may be combined with topical therapy for refractory cases [43]. There is no published experience with voriconazole.

Subcutaneous lesions will often respond to surgical excision alone [44]. Oral systemic therapy with a broad-spectrum azole antifungal agent in conjunction with surgery is frequently employed and has been used successfully, particularly in immunocompromised patients [45, 46].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree