Figure 16.1. Acute dacryocystitis. Note swelling below the nasal corner of the right eye.

Dacryoadenitis, or infection of the lacrimal gland, is uncommon. Patients present with swelling in the lateral portion of the upper lid. Acute infection is most often due to S. aureus or streptococci, but Epstein–Barr virus may cause acute dacryoadenitis in mononucleosis. Chronic dacryoadenitis is usually seen as part of Sjogren’s syndrome, sarcoidosis, or other inflammatory conditions, although Mycobacterium tuberculosis may rarely cause chronic dacryoadenitis. Tumors cause 25% of cases of chronic lacrimal gland enlargement.

Canaliculitis is usually a chronic infection of the canaliculi due to Actinomyces israelii, which forms concretions (“sulfur granules”). Staphylococci and streptococci are other etiologies. Treatment is usually office curettage of the concretions, and/or topical antibiotic eyedrops. See also Chapter 9, Infection of the salivary and lacrimal glands.

Periorbital infections

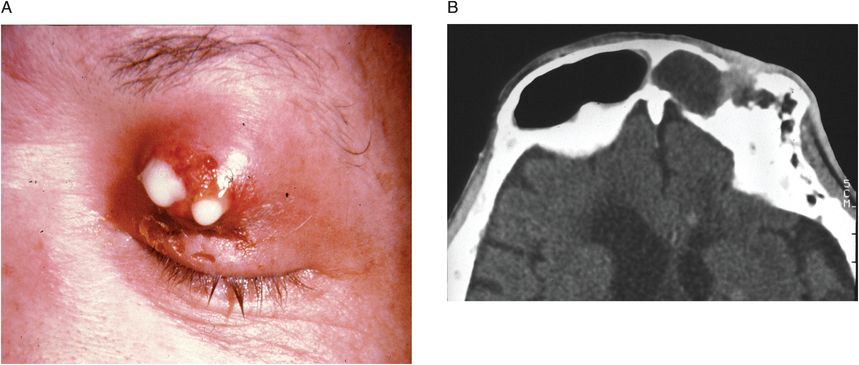

The term periorbital cellulitis is commonly used but is imprecise, as it does not distinguish between preseptal cellulitis and orbital cellulitis. The term orbital cellulitis is often used to include subperiosteal and orbital abscesses as well as orbital cellulitis. The barrier between the preseptal and orbital soft tissues is the orbital septum, a fibrous membrane that arises from the periosteum of the orbital rim and extends to the tarsal plates of the lids. The distinction between preseptal and orbital infections is important, as preseptal infections are not vision threatening and almost never extend into the orbit, whereas orbital infections may rapidly cause vision loss. Patients with either preseptal cellulitis or orbital cellulitis present with swollen, red lids (Figure 16.2). The lids may be swollen shut, but it is essential to open them and examine the eye in order to determine if there are any “orbital signs.” Orbital signs are: decreased vision, proptosis, and limitation in extraocular movement. Patients with orbital infections have at least one of these three features, while patients with preseptal cellulitis have none. Both preseptal and orbital cellulitis occur more often in children than in adults. Sinusitis is the etiology of 80% to 90% of these infections in any age group. The ethmoid sinus is the source of most infections, as it is separated from the orbit by the “paper-thin” bone, the lamina papyracea. However, frontal sinusitis may also lead to orbital infections, often from acute bacterial superinfection of a previously undiagnosed mucocele that has eroded the frontal sinus floor (orbital roof) by chronic pressure (Figure 16.3A, B).

Figure 16.2. Lid swelling and erythema, shown here, are features of both preseptal and orbital cellulitis; opening the eyelids is necessary in order to distinguish these entities.

Figure 16.3 (A) Purulent drainage in upper lid from frontal sinusitis (superinfection of chronic frontal sinus mucocele). (B) CT of patient shown in A. Chronic frontal sinus infection had led to erosion of the floor of the frontal sinus, which is also the roof of the orbit.

Preseptal cellulitis is similar to facial cellulitis, and is an infection of the superficial lid skin and preseptal soft tissues. It presents as unilateral redness and swelling of the eyelids, but with normal vision and extraocular movements. There is no proptosis. The etiology is ethmoid sinusitis in most cases. The bacterial etiology of the cellulitis is unknown but presumed to reflect the common causes of acute sinusitis, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, in addition to S. aureus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree