Patient Safety

Moi Lin Ling

INTRODUCTION

With the release of the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) report on patient safety, To Err Is Human, several healthcare organizations have responded with the development of patient safety programs. Patient safety refers to the freedom from injury or illness resulting from processes in healthcare (1). Many patient-care processes are interlinked through varied systems involving multiple handoffs. The possibility of medical errors increases with the level of complexity of care. This is not surprising because medicine remains very much an inexact, hands-on endeavor. Patients are at greater risk than nonpatients, and medical interventions are by their nature high-risk procedures with a rather narrow margin for error.

An error is defined as an unintended act, either by omission or commission, or by an act that does not achieve its intended outcome (1). This may be either a near miss or an incident in which the error results in an adverse outcome for the patient. Healthcare organizations are highly complex systems with thousands of interlinked processes that can go wrong. A healthcare-associated infection (HAI) is one of the possible outcomes of processes that did not turn out right. Other incidents considered as healthcare errors include incorrect diagnosis, inappropriate use of tests or treatments, wrong site surgery, medication errors, transfusion mistakes, patient falls, decubitus ulcers, phlebitis associated with intravenous lines, preventable suicides, and so on.

The IOM report estimated that healthcare errors occur in about 3% to 4% patients with ~2 million HAIs occurring annually in U.S. healthcare facilities, with an average of each intensive care unit (ICU) patient experiencing two errors a day (1). HAIs represent a major cause of death and disability worldwide (2). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 1.4 million people worldwide suffer from HAIs at any one time. It also is estimated that 2 million HAIs occur in the United States annually with about 80,000 deaths; in England, an estimated 5,000 HAI deaths occur annually. The economic burden is large, with an estimated annual cost of US$ 4,500 to 5,700 million a year in the United States and £1,000 million annually to the National Health Service in the United Kingdom (2).

The Swiss cheese model of system accidents proposed by James Reason (3) gives a good explanation as to how system issues play a key role in patient safety. Defenses, barriers, and safeguards have many holes just like slices of Swiss cheese. Although these systems are to prevent errors, ironically, errors will lead to bad outcomes if the holes are lined up in a manner to allow an adverse event to pass through unstopped. It is not difficult to appreciate this; we are all too familiar with the many system factors that contribute to an HAI. A key process in prevention of surgical site infection (SSI) is the timely delivery of appropriate antimicrobials to a patient at anesthesia induction (4). This process has many interlinked steps to contribute to a successful timely delivery of SSI prophylaxis: (a) the development of evidence-based guidelines on the prophylaxis regime, (b) the collaboration of the anesthesiologist with the surgeon in adhering to the guidelines (i.e., agent and timing), (c) the availability of the appropriate antimicrobial at the time of need, and (d) the act of administering it by the anesthesiologist at the time of induction. A break in any part of this process will lead to noncompliance with the guidelines and then to possible SSI development.

Errors occur because of basic flaws in the systems of a healthcare organization. Hence, in contrast to previous error reviews that assumed that these were the result of bad behavior, incompetence, negligence, or corporate greed, a new approach in the review of incidents is process review in an attempt to identify gaps in the system that need improvement.

Therefore, to improve patient safety, the prevention of errors points to designing safer systems of care. The second IOM report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, recommended that a quality healthcare system be characterized as one that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable (5). The key challenge will be the redesign of healthcare organizations to meet these expected characteristics.

BUILDING THE SAFETY CULTURE

Safety culture has been said to be the greatest challenge in the healthcare system: “The biggest challenge to moving toward a safer healthcare system is changing the culture from one of blaming individuals for errors to one in which errors are treated not as personal failures but as opportunities to improve the system and prevent harm” (5). The safety culture refers to a state in which there is a willingness to report all safety events and near misses without fear of retribution, but with an understanding of accountability (1). Staff have the ability to speak up when they have concerns. Having the understanding that each is accountable for the safety in the organization, staff want to work in teams to help each perform his or her part well. To allay all fear and anxiety and remove the blame and shame culture, the systems approach is used to analyze safety issues. In this approach, processes are examined to appreciate how they may lead to errors instead of focusing on individual blame. An integrated system is required to support the safe behavior. The organization sets the philosophy and values for an integrated pattern of behavior. Open communication about safety concerns and a nonpunitive environment can come about only when the leaders of the organization make it possible. In building a learning

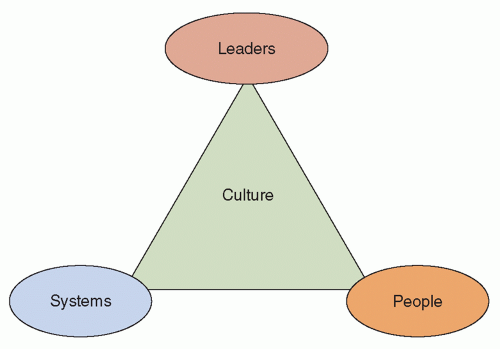

organization, which learns from errors, organizational change has to happen. Structure, processes, goals, and rewards will have to be aligned with improving patient safety. The patient safety triangle is an illustration that helps appreciate how the patient safety culture can be developed (Figure 48.1).

organization, which learns from errors, organizational change has to happen. Structure, processes, goals, and rewards will have to be aligned with improving patient safety. The patient safety triangle is an illustration that helps appreciate how the patient safety culture can be developed (Figure 48.1).

THE ROLE OF LEADERS

Leaders play a key role in developing and shaping the safety culture. They lead the change and are responsible for setting the direction for an organization. Following the example of The Joint Commission’s (TJC) annual patient safety goals (6), setting annual goals to include patient safety helps the organization to express its commitment to building a safe environment for its patients. Leaders also lead by setting examples. Its commitment of leaders to patient safety will have to be expressed in action. Resources will have to be provided to enable the program to succeed. Healthcare organizations committed to safety need to appoint a patient safety officer, usually someone of a senior-level position within the organization who will work with both administrative and clinical leaders (7). This person must have a strong partnership with the chief executive officer to successfully develop and deploy a comprehensive patient safety program as he or she plays a significant role in supervising the patient safety program. In addition to personnel, other resources may be required (e.g., budget set aside to improve the systems, enable access to safety devices or equipment). The tone is set when senior management conducts safety walkabouts on a regular basis. These executive walkabouts have been demonstrated to be successful in not only building staff confidence in management but, more importantly, engaging staff in giving contributory feedback or suggestions for making a safer environment (8). Greater synergy is present when the infection preventionist joins the patient safety walkabout, which will help to foster closer relationships between the infection control team and the ground staff.

THE PATIENT SAFETY TRIANGLE: SYSTEMS

Systems influence safety. A reporting system of incidents made easy or user-friendly helps to ensure good reporting of incidents and near misses. Anonymous reporting has been used to encourage reporting of near misses. The database of incidents from the reporting system is a wealth of information where learning points may be gathered to build a better and safer workplace. Equally important to tracking and monitoring indicators from this database is the analysis of selected critical events or sentinel events. The root cause analysis (RCA) methodology is a quality tool used in analyzing these sentinel events. The steps for this RCA analysis as recommended by TJC may be summarized (9) as follows:

Organize a team.

Define the problem using brainstorming.

Study the problem.

Determine what happened.

Identify contributing process factors.

Explore and identify risk-reduction strategies.

Formulate recommendations for improvement actions.

Implement improvement plan.

Develop measures of effectiveness.

Evaluate implementation of improvement efforts.

The final step of evaluation of implementation of improvement measures is an equally important step not to be ignored. This is aided in a system of required feedback on effectiveness of measures implemented within a set time frame by the authority receiving the sentinel event reports.

Fallibility is part and parcel of the human condition. We may not be able to change the human condition, but we are able to change conditions under which people work. Design management entails designing work so that it is easy to do it right, but very difficult or almost impossible to do it wrong. Design management is part of change management. Several methods may be adopted:

Reduce reliance on memory (e.g., the use of posters to illustrate the seven steps in hand hygiene).

Reduce or simplify steps in processes.

Use standardization (e.g., standardize the device for phlebotomy in an effort to reduce sharps and needlestick injuries and ensuring good-quality blood specimens). Use constraints and forcing functions to achieve desired behavior (e.g., only consultants/attendings may prescribe the use of vancomycin [to avoid inappropriate use of vancomycin in an effort to control the incidence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE)]).

Use protocols and checklists (e.g., the checklist used in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement [IHI] 100K Lives Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia prevention bundle comprising four components: (a) elevation of the head of the bed to between 30° and 45°, (b) daily “sedation vacation,” (c) daily assessment of readiness to extubate, peptic ulcer disease [PUD] prophylaxis, and (d) deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis [unless contraindicated] (10)).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree