PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Part of “CHAPTER 99 – PREMENSTRUAL SYNDROME“

The pathophysiology of PMS is unknown. There appear to be two primary determinants. The first is cyclic function of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis, because, without ongoing ovarian activity, the cyclic disruption in mood and behavior does not occur. The second factor is the intensity of coexisting life stresses. Together, they determine the timing and severity of PMS.

The linkage between the diverse manifestations of PMS and the cyclic changes in ovarian steroid production is unknown; some symptoms are probably a direct effect of circulating sex steroids, whereas others are mediated through changes in brain and hypothalamic neurotransmitters. Breast tenderness and enlargement are likely the result of direct sex steroid effects, leading to localized proliferation of ductal tissue and intralobular edema, whereas constipation and bloating reflect progestational

effects on bowel function. The regulation of behavior, appetite, sleep, and temperature is more complex and probably involves a variety of neurotransmitter systems.

effects on bowel function. The regulation of behavior, appetite, sleep, and temperature is more complex and probably involves a variety of neurotransmitter systems.

Numerous theories of pathophysiology have been advanced, some of which are invalid and none of which are entirely satisfactory.7 Several are described in the following section.

ABNORMALITIES OF ESTROGEN, PROGESTERONE, OR TESTOSTERONE

Studies purporting to show abnormal levels of estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone in PMS suffered from significant methodologic flaws. Subsequent investigations have confirmed normal circulating levels of gonadal steroids.8,9 The demonstration of normal pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in the luteal phase challenged the long-held supposition that disordered neuroregulation of corpus luteal function could be implicated in PMS.10 Treatment with progesterone vaginal suppositories was popularized as a means to correct the postulated progesterone deficiency; however, numerous randomized double-blind trials have since failed to demonstrate the efficacy of this therapy.11,12

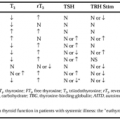

Contrary to the widespread view that estrogen excess in the circulation triggers PMS, some evidence supports the concept that central (hypothalamic) estrogen deficiency may be the inciting factor.13 Many women with PMS experience a brief period of intense symptoms coinciding with the drop in circulating estrogen that accompanies ovulation at midcycle (Fig. 99-1, pattern C). Women with PMS have a high incidence of hot flushes at the time they are symptomatic, in contrast to age-matched controls, who infrequently show this manifestation.6 Whether central estrogen deficiency could occur in the face of normal circulating estradiol levels caused by progesterone-induced depletion of hypothalamic estrogen receptors is speculative; however, this might provide the “missing link” to connect ovarian cyclicity with changes in central neurotransmitters.14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree