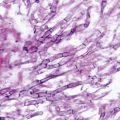

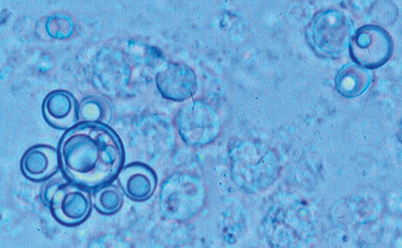

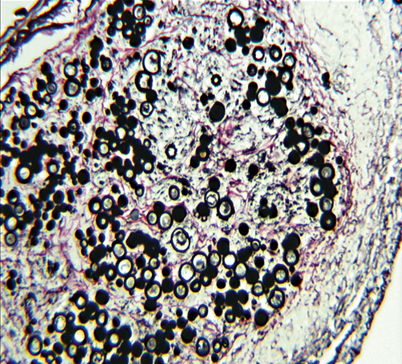

Fig. 19.1

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis yeast cell surrounded by multiple budding daughter blastoconidia (“pilot’s wheel”)

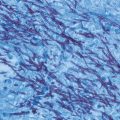

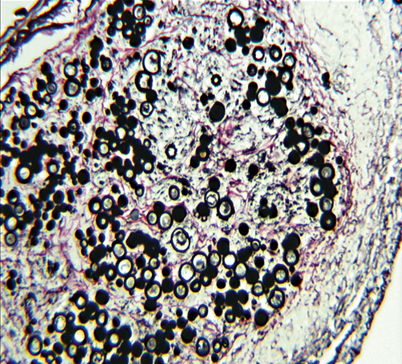

Fig. 19.2

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in tissues. Note abundant round to oval yeast cells enclosed in a granuloma. One cell has multiple buds, while other cells appear empty and degenerated. Gomori Methenamine Silver stain (GMS)

Fungi in the genus Paracoccidioides appear to have exogenous habitats in relation to their preferred human hosts but the precise locations of such niches remain unknown [1, 12, 17]. This is why the initial stages of the infectious process can only be surmised on the basis of experimental animal studies which have shown that after inhalation of the infectious particles (conidia, short mycelial fragments) produced by the fungus saprophytic form, they settle into the lungs where they promptly transform into the tissue yeast form [18, 19]. Infection is thus coupled with a thermally regulated transition from a suspected soil-dwelling filamentous form to a yeast-like pathogenic structure [3]. Molecular epidemiology studies have shown that all P. brasiliensis species—including cryptic ones—are distributed preferentially in certain regions within the endemic areas. Thus, S1 polymorphism predominates in Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela; PS2 prevails in Brazil and Venezuela; while PS3 is exclusive in Colombia [2, 3, 9]. P. lutzii occurs preferentially in the central and northern regions of Brazil [4, 9].

Epidemiology

Demographic data have consistently shown that the clinical manifestations of PCM predominate in adults (over 85 % of cases). In healthy Colombian populations, skin testing with paracoccidioidin proved reactive in 10 %, indicating a previous contact (infection) with the fungus [20]. When the same test was applied in Brazil where PCM is of greater importance, the incidence rates were higher especially in the southern, southeastern, and mid-western regions [1, 12]. Additionally, when the gp43 antigen was used for this purpose, higher (43 %) prevalence rates of infection were recorded [21, 22]. Overall, the disease prevalence rates in Latin America are low, 0.33–3 cases per 100,000 inhabitants [23, 24]. In Brazil, mortality rates attributable to the mycosis represent 3 % of all reported cases [12, 25, 26].

As a disease process, PCM is more often diagnosed in males than in females (ratio of 13:1), even though paracoccidioidin skin testing has shown similar infection rates in both sexes [1, 6, 20–22]. This mycosis is relatively uncommon in children, with approximately 5 % of all patients being less than 10 years of age. When children and adolescents (< 14 years old) are set together, approximately 15 % of all cases correspond to this age bracket, with 8 % more being less than 20 years of age [6, 12, 13, 23, 27, 28]. PCM occurs most commonly in middle-aged men (40–60 years), with the exception of immunosuppressed patients who tend to be younger [6, 11–13, 29, 30]. Most patients (73 %) have current or past agriculture-related occupations [1, 6, 11–13, 27, 28].

Risk factors include living and working in these areas, malnutrition, as well as alcoholism and smoking [1, 6, 12, 13]. A direct relation to underlying immunosuppressive conditions, including HIV disease, has not been clearly demonstrated. Sarti et al. found that in a cohort of over 1000 HIV-infected patients, PCM accounted for only 3.3 % of the deaths (in contrast with histoplasmosis which caused 38 % of fatalities) [29]. Morejon et al. estimated that in HIV patients the prevalence of P. brasiliensis coinfection was low, 1.4 % [30]. Isolated case reports of the mycosis in immunocompromised individuals are rarely found [31, 32].

One of the most relevant characteristics of PCM is its restricted geographic limitation to Central and South America from Mexico (23° North) to Argentina (34° South), sparing certain countries within these latitudes (Chile, Surinam, the Guyana, Nicaragua, Belize, most of the Caribbean Islands) [6, 11–13, 27, 28]. Also of note is the fact that within endemic countries the mycosis is not diagnosed everywhere, but in areas with relatively well-defined ecologic characteristics. These characteristics include the presence of tropical and subtropical forests, abundant watercourses, mild temperatures (< 27ºC), high rainfall (2000–2999 mm), all of which favor crops, such as coffee and tobacco [33].

According to geospatial technologies, association between climatic factors and clinical diagnosis of this mycosis, tend to indicate that Paracoccidioides spp. complex would occur preferentially at sites where the environment has a high rainfall index and the soils show optimal permeability, a combination associated with high relative humidity and abundance of vegetation and watercourses [33]. Estimates indicated that during the rainy season the water volume is high, and temperatures oscillate between 18 and 28 °C, conditions that appear favorable for spore formation and aerial dispersion of the fungus [9, 12, 33, 34]. In a southern region of Brazil, the influences of soil water storage, absolute air humidity higher than normal and presence of the climatic anomaly caused by the 1982/1983 El Niño Southern Oscillation, were shown to be associated with a cluster of acute/subacute cases appearing within a lapse of 1–2 years [35].

Approximately 80 PCM cases have been reported outside the endemic areas, namely, in North America, Europe, and Asia. Of note, every patient had a record of previous residence in recognized endemic countries [36, 37]. These cases demonstrate that P. brasiliensis primary infections can remain dormant for long periods (mean of 13 years) from the time of infection to the moment of disease manifestations [17]. No data on imported P. lutzii cases have been presented. Latency/dormancy may explain why the habitat(s) corresponding to members of the Paracoccidioides complex had not been precisely demonstrated, as with the usual delays in diagnosis, and the mycosis slow progression, one tends to forget the site and type of activities that had led to primary infection [14]. No outbreaks have been reported and the isolation of the fungus from nature (e.g., soil) has seldom been successful [38]. By means of molecular studies (nested polymerase chain reaction, PCR), sampling by aerobiological procedures detected ITS sequences in air samples that were highly similar with the homologous P. lutzii sequences kept at the GenBank database, even if the fungus could not be isolated from the environment by regular culture isolation strategies [39].

Pathogenesis and Immune Response

Lack of data on two main issues, namely, the habitat of P. brasiliensis/P. lutzii and the manifestations of primary infection, have hindered the understanding of the initial steps in the pathogenesis of PCM. Experimental animal models have been produced by initiation of the paracoccidioidal infection via inhalation of conidia (elements small enough (< 5 m) to reach the alveoli) which transform into yeast cells [18, 19]. The fungus then multiplies in the lung parenchyma and proceeds to disseminate by the venous/lymphatic routes to extrapulmonary organs (Fig. 19.3). Infection gives rise to an intense host response with alveolitis and presence of abundant neutrophils leukocytes engulfing the fungus, cells that are later on replaced by migrating mononuclears which, in turn, convert into epithelial cells thus initiating the formation of granulomas and attracting various subtypes of T lymphocytes of which the relative proportions depend on the host immune status [1, 40–42]. In mice with pulmonary infection with P. brasiliensis, fungal load was controlled by CD8 + T cells, whereas antibody production and delayed type sensitivity reactions were regulated by CD4 + T cells [43]. It has been shown that lymphocytes from PCM patients are poorly activated, express low levels of interleukin 15 receptor alpha (IL-15R alpha) and produce only basal levels of cytotoxic granules [43–46]. These findings may account for the observed defect in vitro cytotoxic activity [40, 41, 44, 46].

Fig. 19.3

Presumed natural history of paracoccidioidomycosis

The characteristics of the immune responses in patients with overt disease have been the subject of numerous studies. Immune reactivity to P. brasiliensis antigens is characterized by depressed Th1 cellular immune responses that revert to normal or almost normal ranges with treatment and patient improvement [46, 47]. Patients with the acute type disease not only have depressed Th1 but have also polarized Th2 responses, characterized by the increased release of the cytokines IL-4, IL–5, and IL-10, high levels of circulating anti-P. brasiliensis antibodies of the immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) and immunoglobulin E (IgE) subclasses, and marked eosinophilia [41, 42]. This pattern is reflected by abundant fungal multiplication and extrapulmonary dissemination with progression of disease [43, 44, 46]. This Th-2 polarization is regularly reverted with treatment. A Th1 cellular immune response to P. brasiliensis is detected in those individuals who were once exposed to the fungus but did not develop the disease [43]. More recently, a role for T-regulatory cells in cell-mediated immune suppression has been found in patients with active disease, which was also reverted with treatment [41]. The participation of the newly described Th17, Th21, and Th9 subsets in the patients’ immune response has recently been documented revealing Th17 and Th21 responses in the case of the adult type disease while Th9 response was detected mostly in the juvenile type disease [46].

The factors that determine the different outcomes of the infection are not known. In most instances, the subclinical infection is resolved, possibly leaving viable yeast cells that eventually may enter into a dormant-like state for decades [14]. The chronic adult-type disease would then originate from reactivation of these dormant yeast cells and this would explain why these patients tend to develop a chronic, progressive disease, marked by pulmonary damage, and accompanied, in most cases, by dissemination to the lymphatic system, the mucosa, the adrenals, the skin, and other organs [1, 11–13, 16, 23]. Lung damage can progress to fibrosis leaving behind sequelae with variable impact on respiratory function, reinforcing the importance of early diagnosis and treatment [1, 16, 47, 48]. In the rare instances, when the primary infection is not checked by the host’s immune responses, P. brasiliensis disseminates through the lymphohematogenous route resulting in the acute- or juvenile-type disease [1, 42, 49, 50]. Overall, the prevalence of the disease is low even in endemic areas, while that of infected-only individuals is high, reaching up to 46 % of the population in certain highly endemic settings according to skin testing studies [1, 20–22, 51].

In PCM, polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) have been implicated not only in phagocytosis and pathogen destruction but also in granuloma formation. In cases presenting only loose granulomas, a greater quantity of fungi are to be found in comparison to those corresponding to well-organized granulomas. In either case, neutrophils are present in tissues and participate in granuloma formation largely contributing to the inflammatory response [52]. The major biological significance of granuloma is the limitation of the infection to a local area but if such formation is loose, dissemination would ensue [1, 53].

Antibodies are detected in most PCM patients although the isotypes differ according to clinical type. Thus, the reactivity of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) to certain antigens was greater in patients with the acute form while immunoglobulin A (IgA) was more reactive in those with the chronic form [54–56]. Nonetheless, their role in the pathogenesis of human disease is still unclear.

Clinical Manifestations

PCM is a disorder characterized by protean manifestations that in most patients tend to run a chronic progressive course involving various organs and systems with mortality rates that average 0.9 per 1 million inhabitants in Brazil [46]. Most patients exhibit constitutional symptoms, such as general malaise, asthenia, adynamia, weight loss, and fever, as well as symptoms related to the infected organs. The primary infection occurs in the lungs, but often neither the patient nor the clinical examiner finds abnormalities at this site. On the basis of the clinical presentation and the host immune response to PCM, the disease is categorized as (1) subclinical infection, or (2) symptomatic infection, which is subdivided in two forms, the acute/subacute juvenile and the chronic adult type. A third residual form characterized by fibrotic sequelae is also recognized [1, 6, 11–13]. On the basis of gallium image studies, it is presently accepted that the various manifestations of PCM entail multiple organ involvement, thus negating the former division of the disease into a unifocal or a multifocal process [48]. With the increase in the number of immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with AIDS, the mycosis is being recognized more frequently [25, 26, 29, 30, 57]. In such patients, the corresponding clinical presentation does not allow to categorize the process as chronic or acute but rather as a mixed (opportunistic) form [58–62]. Table 19.1 summarizes the key factors leading to consider the diagnosis of paracoccidioidomycosis.

Table 19.1

Key factors leading to consider the diagnosis of paracoccidioidomycosis

History of residence in an endemic country (even if many years previously to initiation of symptoms/lesions) |

History of working in agriculture or related occupations. Mining also to be considered |

Being an adult male with a chronic, progressive illness |

Complaints related to external manifestations (mucous membrane, skin, and/or lymph node enlargement/draining) |

General malaise, weight loss, fever |

Signs and symptoms of adrenal gland dysfunction |

No major pulmonary signs/symptoms contradicted by X-rays or imaging abnormalities |

In children, young adults and immunocompromised individuals (mainly AIDS), hypertrophy of lymph node structures and/or involvement of liver/spleen |

Multiple skin lesions or bone abnormalities in the above mentioned groups |

Remember: Paracoccidioidomycosis often exhibits protean manifestations thus hindering proper diagnosis |

Subclinical Infection

The subclinical infection has no special characteristics and is detected mostly by a reactive paracoccidioidin skin testing, and sometimes by abnormal chest radiographs [11–13, 20]. Additionally, more sensitive serological or molecular techniques may also disclose healthy infected people [37, 41, 46, 47, 55]. However, P. brasiliensis may remain latent in the infected host giving rise to symptomatic PCM years after the initial contact, as demonstrated by the cases diagnosed outside the mycosis endemic areas, all of whom had the opportunity to become exposed to the fungus in their native countries where they had acquired the primary subclinical infection [14, 34, 35].

Symptomatic Infection

The clinically manifested disease varies with patient’s age and immune status.

Juvenile-Type Disease

The juvenile-type disease is a serious disorder that afflicts children and immunocompromised individuals of either sex; it represents less than 10 % of all cases. Involvement of the reticuloendothelial system organs with lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, and/or splenomegaly characterizes this form. Skin lesions, often multiple, are observed regularly along with bone involvement. Constitutional abnormalities such as fever, marked weight loss, and general malaise are hallmarks and become associated with anemia, eosinophilia, and hypergammaglobulinemia [12, 13, 28, 49, 50]. Abdominal and digestive tract manifestations, such as presence of abdominal masses, lymph node enlargement, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal distention or pain, and ascites, are also more common than in the chronic adult disease. Although respiratory symptoms are infrequent, in the juvenile patients, the fungus can be seen in respiratory secretions, and computed tomography studies not infrequently reveal abnormalities such as enlarged hilar lymph nodes, or, more rarely, miliary infiltrates [11–13, 48]. The juvenile-type disease may evolve rapidly, in weeks, and consequently, prompt diagnosis accompanied by instauration of antifungal therapy and supportive measures are required [11–13, 49–51, 57]. Mortality rates are higher than in the adult disease, reaching 10% in some series [57].

Chronic Adult-Type Disease

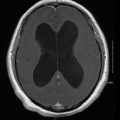

The chronic, adult-type disease predominates in all case series (80–90 %) [58]. It occurs preferentially in male patients (13 men: 1 female), aged 30 years or more with agriculture-related occupations. The disease course is characterized by protracted pulmonary and extrapulmonary organ damage especially of the mucous membranes and the skin with the lesions tending to be ulcerative, granulomatous, and infiltrated (Fig. 19.4) [58, 59]. Association with AIDS is not particularly notorious [60, 61]. Sialorrhea, dysphagia, and dysphonia are common. Regional lymph nodes are hypertrophied and may spontaneously drain forming fistulae. The adrenal glands may also become involved, with associated symptoms of adrenal deficiency. CNS involvement is more frequent than thought before and its diagnosis is difficult due to the fact that its clinical manifestations, computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings are not specific [62, 63]. At least 80 % of these patients also present pulmonary abnormalities [12, 13, 58, 59].

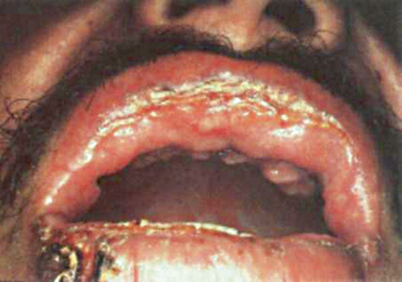

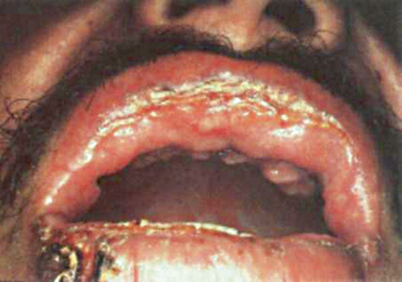

Fig. 19.4

Cutaneous and mucosal lesions in a patient with paracoccidioidomycosis. Note lip’s edema, ulceration, and scarring

High-resolution CT studies have revealed lung abnormalities in 98 % of the patients with architectural distortion, reticulate and septal thickening, and centrilobular and paraseptal emphysema [64–66]. Chest radiographs reveal mixed infiltrates, mostly interstitial but at times also alveolar; these are predominantly located in the central and lower fields respecting the apices (in contrast with tuberculosis) and are bilateral [64–66]. Sequelae, represented by pulmonary fibrosis, were observed in most patients with 30 % of them developing significant respiratory limitation [48, 59, 64–66]. Not infrequently, image studies show more important lesions in comparison with the patient’s symptoms or even with findings at auscultation [67–69]. Fibrosis may also occur in other organs and systems and is regularly associated with functional impairments (Fig. 19.5) [1, 12, 13]. In absence of treatment, adult mortality may be as high as 30–45 % based on multiple series [25–28, 51, 69].

Fig. 19.5

Pulmonary paracoccidioidomycosis. Note abundant fibronodular infiltrates in central fields and basal bullae

Disease in Immunocompromised Patients

Paraccocidioidomycosis in patients with cancer, especially with hematological malignancies, frequently results in a disease with features of both the acute and chronic forms [12, 68, 70]. In patients having an impaired immune system, the pulmonary findings corresponding to those of the chronic adult-type disease which are frequently associated with signs of lymphohematogenous dissemination, such as lymph node enlargement, hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly, and skin lesions, features of the acute type disease [49, 50]. In regard to patients with AIDS, the association between both diseases may represent 5 % of all PCM cases [29, 30, 60, 61]. Although the mycosis develops mainly in patients with low CD4+ lymphocyte counts (< 200 cells/μl), response to antifungal therapy is, in general, similar to that observed in non-immunocompromised patients with PCM [12, 29, 57]. Additionally, in severe cases, corticosteroids appear beneficial [71]. Despite the immunodeficiency, specific antibodies are detected in over 70 % of the cases [72]. Some clinicians discontinue antifungal therapy in patients who have responded to treatment and appear clinically cured when the CD4 lymphocyte count rises to more than 200 cells/µL.

Diagnosis

Direct Examination and Histopathology

In clinical specimens from oral, pharyngeal, and cutaneous lesions, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, lymph nodes, adrenal glands, or biopsy materials from other tissues, P. brasiliensis can be identified in up to 85 % of the cases by means of fresh or wet potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations; as well as on calcofluor and immunofluorescence preparations. P. brasiliensis appears as an oval to round translucent-walled yeast cell, often having multiple peripheral buds (typical “pilot wheel” configuration) (Fig. 19.1). Histopathologic preparations stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Gomori methenamine-silver (GMS), or periodic acid-Schiff are also useful as they reveal the multiple budding yeast elements, especially within granulomatous foci (Fig. 19.6 19.6). It is important to differentiate P. brasiliensis from Cryptococcus neoformans, Blastomyces dermatitidis, and even Histoplasma capsulatum [1, 6, 11, 16, 47, 73–75].

Fig. 19.6

Tissue biopsy with abundant Paracoccidioides brasiliensis yeasts enclosed within a granuloma. Gomori Methenamine Silver stain (GMS)

Culture

Isolation of P. brasiliensis from clinical specimens requires a battery of selective and nonselective culture media, such as Sabouraud dextrose, brain–heart infusion (BHI) plus glucose, or MycoselTMagar. The addition of antibacterial drugs (chloramphenicol or gentamicin) and mold inhibitors (cycloheximide) to the media has resulted in improved recovery rates of around 80 %, thus providing a useful differential tool in identification of the fungus [1, 6, 11, 16, 73–75]. Modified Sabouraud’s (Mycosel) agar and yeast extract agars incubated at room temperature (19–24 °C) are the best media for primary isolation but the growth is slow and may take 20–30 days. Microscopically, the mold shows thin septated hyphae and chlamydospores (15–30 μm). Under conditions of nutritional deprivation, some isolates produce conidia, which vary in structure from arthroconidia to microconidia, and measure less than 5 μm. Conidia respond to temperature changes, germinating into hyphae at 20–24 °C or converting into yeasts at 36 °C on appropriate media. The mycelial form is not distinctive and dimorphism must be demonstrated for identification [1, 6, 11, 16, 73–75]. At 37 °C the P. brasiliensis yeast form grows in 8–10 days as a cerebriform, cream-colored colony. Microscopically, oval to spherical yeast cells (2–40 μm) are observed. As mentioned above, the large mother yeast cell bearing multiple buds (pilot’s wheel) is characteristic of this fungus [1, 6, 16, 73, 75]. There is no commercial DNA probe test for identification of P. brasiliensis.

Immunodiagnostic Tests

Immune-based methods for antibody and antigen detection are useful not only for diagnosis but also for monitoring the patient’s treatment course [74–77]. Antibody detection has been based upon antigen preparations using either mycelial or yeast cell lysates. While a series of immunoreactive antigens (27, 43, 70, and 87 kDa) are present in these lysates, the predominant antigen is the 43 kDa glycoprotein, gp43 [76–81].Because of its simplicity, the gel immunodiffusion (ID) test is typically used in endemic countries. This test demonstrates circulating antibodies in 65–95 % of the cases and is highly specific. Commercial mycelial-form culture filtrate antigen can be obtained for in-house use in ID from IMMY (Paracoccidioides ID Antigen; IMMY), but its sensitivity has not been widely studied [75]. Complement fixation (CF) test is performed with P. brasiliensis yeast-form culture-filtrate antigen but this reagent is not commercially available. CF is less specific than the ID test, and cross-reactions can occur in cases with histoplasmosis. However, CF titers of ≥ 1:8 are considered presumptive evidence of PCM and falling CF titers are often predictive of successful treatment [75–77].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree