Osteoarthritis: Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is defined as boney inflammation of a joint or joints. OA is the most common form of arthritis in the United States and Europe. Given the prolonged life expectancy in the United States and the aging of the “baby boomer” cohort, the prevalence of OA is expected to increase further. Although the precise cause of OA is unknown, it is likely that multiple causes and many factors influence disease expression.

Epidemiology, Causes, and Predisposing Factors

Epidemiological and observational studies provide important clues to the mechanisms by which OA develops and progresses and, thus, identify risk factors that might comprise intervention targets for OA prevention and management.

Advanced age is the strongest risk factor for the development of OA across all anatomical sites. Prevalence rates for both radiographic OA and, to a lesser extent, symptomatic OA (moderate or severe) increase with age, with a steep rise after the age of 50 years in men and age of 40 years in women. Radiographic OA of the hand is the most prevalent form, followed by knee, then hip. It is not unusual to find incidental radiographic OA in an otherwise asymptomatic older patient. Symptomatic OA of the knee and hip OA are the most prevalent in both sexes, with symptomatic involvement of the hands increasing in women beginning at menopause.

Changes in the hormonal milieu are thought to contribute to OA pathogenesis and are supported by reports of reduced risk of incident hip OA in women receiving hormonal therapy. However, estrogen/progestin replacement has not been proven to reduce the chance of developing knee pain or disability in women with knee symptoms. Whether estrogen or hormonal therapy is beneficial with regard to OA thus remains controversial and further emphasizes that OA symptom and disease pathogenesis likely develop through different mechanisms.

Joint trauma of a severity that causes swelling and discomfort lasting several days or longer has been shown to increase risk of knee OA. Prior surgical removal of a meniscus in the knee is also a predisposing factor to OA of the knee. Meniscectomy is associated with a sixfold increase in risk for development of radiographic OA, even if limited rather than total meniscal resection is employed. Obesity, female sex, and preexisting early-stage OA of the knee and concurrent hand OA compound the risks incurred following meniscectomy. Occupation- and sports-related repetitive injury and physical trauma contribute to the development of OA of specific joints (e.g., knees in soccer players, elbows of baseball pitchers, and upper limbs of air hammer operators) and account for occurrence at sites not usually affected by OA. Although the prevalence of knee OA is greater in adults who have engaged in occupations that require repetitive bending and strenuous activities, an association with intense exercise or recreational physical activity such as jogging has not been proven. Joint malalignment and varus–valgus laxity increase the risk of developing OA. Malalignment of the knee appears to explain some of the risk of knee OA progression attributable to obesity. Altered alignment, as in the case of acetabular dysplasia, may also increase risk of hip OA. Although laxity and malalignment may coexist, laxity independently increases risk of OA.

Obesity and excess weight comprise an important risk factor for the development and progression of knee, hip, and even hand OA. It is estimated that persons in the highest quintile of body weight have up to 10 times the risk of knee OA than those in the lowest quintile. Although mechanical factors are assumed to explain the increased risk of knee and hip OA associated with excess weight and obesity, the association with hand OA with weight raises the possibility of alternative mechanisms.

Weakness of the knee extensor muscles appears to be both a consequence and a risk factor for the development of knee and hand OA. However, muscle strengthening has not been proven to protect individuals from progression of OA. In fact, higher strength has been associated with greater risk of progression in malaligned knees, and also of proximal interphalangeal and carpal–metacarpal joint OA in men and metacarpophalangeal joint OA in men and women.

Classification and Pathophysiology

The term “primary OA” is used to denote idiopathic OA in contrast to “secondary OA” that results from damage induced by another process (gout, rheumatoid arthritis, and bacterial). Although OA can involve any joint, it is most prevalent in the fingers and thumb base of the hands, knees, hips, and also spine. The classification system developed by the American College of Rheumatology (Table 116-1) integrates patient age, radiographic features, clinical symptoms, and physical abnormalities of the hands, knees, and/or hips. Such classification systems define phenotypes of clinical presentation that may lend clarity to the development of specific treatment modalities in the future. OA that is radiographically apparent but not associated with clinical features specified in the ACR criteria is referred to as “radiographic OA.”

HAND | KNEE | HIP |

|---|---|---|

Hand pain, aching, or stiffness | Knee pain | Hip pain |

and | and | and |

Hard tissue enlargement of two or more joints | Radiographic osteophytes | Two or more of the following: |

and | and | *ESR <10 mm/h |

Fewer than three swollen MCP joints | One or more of the following: | Radiographic femoral or acetabular osteophytes |

and | Age ≥50 yr | Radiographic joint space narrowing |

Two or more DIP joints with hard tissue enlargement | Morning stiffness <30 min | |

or | Crepitus on motion | |

Deformity in two or more select joints† |

Cartilage degeneration is the hallmark of this disease, with fibrillation and ulceration that begins superficially and eventually extends into deeper layers. In addition, subchondral bone abnormalities and focal synovial inflammation can also be observed. These pathological characteristics are thought to arise owing to disruption of the balance between degradative and repair processes necessary to maintain joint health. Inflammatory cytokines, matrix degrading metalloproteinase enzymes, and chondrocyte apoptosis are likely contributors to this process. Osteophytes develop later and are thought to represent attempted repair. The process by which aging is theorized to increase risk of OA is depicted in Figure 116-1.

Figure 116-1.

The process by which aging is theorized to increase risk of OA is depicted. Some of the mechanisms and mediators demonstrated in cellular and system aging are relevant to cartilage and periarticular structures. These changes may predispose the aging individual to altered biomechanics that increase risk of joint injury to which repair is attempted but eventually fails.

Presentation

The most common initial symptom of OA is stiffness, which is most noticeable on awakening in the morning and after periods of inactivity. These symptoms are usually temporary and rarely persist for more than 30 minutes. As the disease progresses, patients experience pain with activity, which resolves on resting the joint. With further progression, patients report pain at rest and that awakens them from sleep. Validated questionnaires assessing the severity of painful symptoms referent to specific activities such as walking, stair climbing, and grasping are available and may prove useful in clinical settings, although these are primarily used in research studies of OA. Similarly, measures assessing the intensity and duration of stiffness may also prove useful—particularly in monitoring treatment response. A history of systemic symptoms such as unintentional weight loss, excessive fatigue, and prolonged morning stiffness that extends beyond an hour suggests an “inflammatory” condition such as polymyalgia rheumatica or rheumatoid arthritis, rather than OA.

Physical examination of a joint with early OA may be completely normal. Subtle prominence of the finger joints and effusion of the knee may be present early. Joint tenderness, warmth, and painful motion may be present. Crepitus may be appreciated by palpating the joint during movement. Bony prominence develop later and are exemplified by Heberden’s nodes of the distal and Bouchard’s of the proximal interphalangeal joints of the fingers (Figure 116-2). These are firm and bony on palpation, in distinction from more inflammatory etiologies that are boggy to palpation. As joint destruction ensues, crepitus and bony prominence become appreciable. Joint laxity or unexpected mobility may be observed on passive joint movement and may suggest incompetence of the supporting ligaments. As the disease progresses, joints may become malaligned and deformed. An example of this is knee deformity that is either varus (knees pointing outward beyond the femoral–tibial line) or valgus (knees pointing inward). Joint motion becomes limited as the disease progresses. Disease severity may be manifested as OA involvement of multiple joints as well as the spine. In these cases, careful examination of each joint is required to ascertain the source of painful symptoms. For example, “hip pain” may arise from OA of the hip, but also may be pain referred from the knee or spine. Similarly, OA of the neck may manifest as shoulder pain. Accurate localization of the source of painful symptoms is required for effective management.

Evaluation

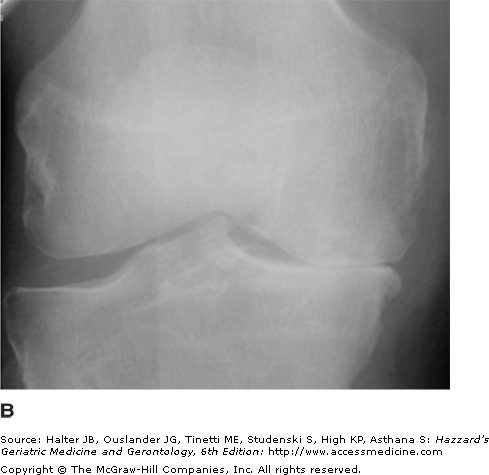

Conventional radiography remains the imaging modality of clinical choice to confirm a diagnosis of OA by the presence of osteophytes, as shown in Figure 116-3. Additional information obtainable from X-ray images includes joint space width and alignment, calcification of cartilage or periarticular structures, and soft-tissue swelling, bony defects (osteomas), and osteopenia and fracture. Scoring schema have been developed and used to assess disease severity as well as confirm disease presence. However, conventional radiographs have limited resolution and are, therefore, not capable of detecting early disease. Additionally, certain views are required to allow measurement of change in specific features (e.g., joint space width and osteophyte size) over time. Although X-rays can be useful in excluding conditions such as fracture and tumor, these can also be misleading because of the high prevalence of incidental radiographic abnormalities in older adults, as discussed further below. Therefore, X-ray abnormalities should be interpreted in the context of clinical history and physical findings or risk, mistakenly attributing symptoms from other illnesses (infection, aneurysm, etc.) to OA.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers promise for earlier detection of OA, since focal defects in cartilage can be identified in painful knees that are still radiographically normal. Furthermore, MRI has contributed to our understanding that OA involves a variety of characteristics (e.g., osteophytes, cartilage defects, and bony abnormalities), which often occur together in one or several regions within a joint in a manner that is highly correlated with persistent painful symptoms, and has led the field to appreciate that OA is not a disease that is limited to cartilage. Moreover, changes in cartilage, bone, and synovium often occur together. MRI also allows visualization of structures important to functional stability of the joint (e.g., ligament and meniscus) and should be obtained to evaluate mechanical symptoms of locking or giveway weakness in knees, instability of the hip, and impingement symptoms of the shoulder. However, clinical discretion is required in determining whether visible structural defects require surgical correction. Additionally, MRI may be useful in distinguishing other intensely inflammatory conditions from OA.

Laboratory studies are generally more helpful to exclude alternative diagnoses such as infectious arthritis, Lyme, or crystalline diseases (gout and CPPD) than to diagnose OA. Several reports of elevated concentrations of C-reactive protein in association with OA support our reconsideration of OA as a mildly inflammatory disease, but it is neither sensitive nor specific enough for diagnostic utility. Additional products of cartilage and bone turnover have been integrated into clinical OA studies but are not applicable to OA management. Collectively, these biologic indicators have contributed to our understanding of the OA process, but, at present, serum, urine, or synovial markers with acceptable test characteristics are not available for diagnostic or prognostic use.

Management

The objectives of OA management are to lessen painful symptoms and improve function and quality of life. The scope of OA management has appropriately broadened beyond medicinal agents to include physical and rehabilitative and other interventions. Primary-care practitioners can set in motion numerous services (e.g., rheumatology, physiatry, physical or occupational therapy, psychology, nutrition, social work, and orthopedic surgery) in pursuit of these objectives. Currently used management options are summarized in Table 116-2.

Patient education |

OA education—cause and treatment |

Weight management |

Exercise |

Nonmedicinal and rehabilitative |

Exercise |

Electrical stimulation |

Ultrasound |

Cryotherapy and thermotherapy |

Acupuncture |

Modalities |

Braces, orthotics, and assistive devices |

Symptom-directed medicinal agents |

Topical agents |

Simple analgesics |

Nutriceuticals |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors |

Narcotic analgesics |

Intra-articular agents |

Potential structure-modifying agents |

Surgical interventions |

Arthroscopy |

Osteotomy |

Arthroplasty |

Restorative surgery |

The effectiveness of OA management is highly dependent on patient compliance. Therefore, patient education should be considered the initial required element in OA management. Educational groups or classes provide an efficient and social vehicle to convey general information pertaining to OA and management strategies. Topics might include warning signs of medication toxicity, exercise, weight management, stress management, sleep hygiene, and general healthy living. Participants in self-management groups report less pain and reliance on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Additional benefits of participation in these programs include boosting self-efficacy, increased physical activity, and lessening the frequency of arthritis-related physician visits. However, program participation does not obviate the need for individualized patient education in matters of medication compliance and drug toxicity monitoring.

Weight loss in obese individuals with OA of the knee can reduce painful symptoms as well as slow disease progression and is, therefore, recommended for all patients who are overweight. In many cases, a structured weight management program with counseling may be required. Although a 10% reduction in weight is considered a reasonable objective, this should be achieved by combined exercise with dietary modification in older adult patients as a result of the additional benefits gained through muscle strengthening.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree