Oral Cavity: Introduction

The oral cavity serves three essential functions in human physiology: (1) the production of speech, (2) the initiation of alimentation, and (3) protection of the host. A discussion of oral–pharyngeal health and function throughout the human life span must consider the impact of any disturbance of these three functions on an older person’s life.

In order to speak, process food, and protect the host from pathogens and trauma, many specialized tissues have evolved in the oral–facial region (Table 42-1). The teeth, the periodontium, and the muscles of mastication exist to prepare food for deglutition. The tongue occupies a central role in communication, and is also a key participant in food bolus preparation and translocation. Salivary glands provide a secretion with multiple functions. Saliva, in addition to lubricating all oral mucosal tissues to keep them intact and pliable, moistens the developing food bolus, permitting it to be fashioned into a swallow-acceptable form. All these tissue activities are finely coordinated, and a disturbance in any one tissue function can significantly compromise speech and/or alimentation and diminish the quality of a patient’s life (Table 42-2).

ORAL TISSUE | FUNCTION |

|---|---|

Teeth | Mastication, bone regeneration |

Periodontium | Mastication, bone regeneration, host defense |

Salivary glands | Lubrication, buffering acids, antimicrobial activity, mechanical cleansing, mediation of taste, remineralization of teeth, oral mucosal repair |

Taste buds | Taste, host defense |

Oral mucosa | Host defense, mastication, swallowing, speech |

Muscles of mastication and facial expression | Mastication, swallowing, speech, posture |

DISEASE | ORAL MANIFESTATIONS |

|---|---|

Dental and periodontal infections | |

Dental caries | Soft to hard discolored defect on tooth surface |

Gingivitis and periodontitis | Erythematous, edematous, and hemorrhagic gingiva, which may be accompanied by gingival recession and tooth mobility |

Viral infections | |

Primary herpes simplex infection | Clear to yellow vesicles that rupture and form shallow, painful ulcers on all mucosal surfaces; gingival tissues inflamed, edematous, and painful |

Recurrent herpes simplex infection | Burning or tingling prodrome in lesion sites (lip, hard palate, attached gingiva); whitish-gray vesicles rupture to form painful ulcers, which then develop a crust |

Herpes zoster | Unilateral vesicular eruptions in areas following the distribution of ophthalmic, maxillary, or mandibular divisions of trigeminal sensory nerves |

Cytomegalovirus | Mononucleosis-like symptoms, petechial hemorrhages, enlarged salivary glands, pharyngotonsillitis |

Fungal infections | |

Pseudomembranous candidiasis | Soft, white or yellow plaques that can be wiped off to expose an underlying erythematous mucosa |

Hyperplastic candidiasis | Leukoplakic or keratotic lesions that cannot be removed by scraping |

Erythemic or atrophic candidiasis | Painful erythematous oral mucosal lesions; tongue appears “bald”; diffuse inflammation of denture-bearing areas |

Angular cheilitis | Erythematous cracked or fissured lesions at the lip commissures |

Salivary gland infections | |

Acute sialoadenitis | Tender salivary gland swelling with purulent discharge on palpation of the gland duct |

Chronic sialoadenitis | Recurrent, tender swellings of salivary gland progressing to a firm and atrophic gland |

The oral cavity is exposed to the external world and is vulnerable to a limitless number of infectious, traumatic, and environmental insults. Extensive mechanisms have evolved to protect the mouth and permit normal oral function. The oral cavity is richly endowed with sensory systems that contribute to the enjoyment of food and alert an individual to potential problems. These systems include mechanisms for taste (and its inextricable relationship with smell); thermal, textural, and tactile sensation; and pain discrimination. Also, saliva plays an important protective role and contains a broad spectrum of antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal proteins that modulate oral microbial colonization. Other proteins maintain the functional integrity of the teeth by keeping saliva supersaturated with calcium and phosphate salts and provide the first role in repairing incipient caries (tooth decay) via a remineralization process.

The use of dental services among older cohorts has improved over the past 40 years in the United States. However, findings from several national surveys indicate that a significant proportion of the elderly population does not see a dental professional on a regular basis and may thus be at risk for developing severe oral medical problems. For example, patients of all ages report more physician visits per year than dental visits, and this difference increases with greater age. More than 25% of the U.S. population aged 65+ years has not seen a dental professional in the past 5 years. In addition, elderly persons who wear complete dentures are four times less likely to visit a dentist than are those with remaining teeth.

These trends may change, however, for several reasons. First, future cohorts of older persons will have experienced improved oral health earlier in life, which will result in more patient visits than previous older-aged cohorts. Second, dental insurance coverage and retirement assets are more available for older-aged dental care than for previous generations of retired individuals. Third, nearly one-third of the elderly population is edentulous, but the prevalence of edentulousness has been decreasing steadily for the past four decades. This has resulted in an increased retention of the natural dentition, and therefore dental caries and periodontal diseases will remain substantial oral health concerns for older individuals in the future.

Half of adults aged 55+ years in the United States wear an oral prosthesis (partial or full denture), and 60% of them report problems with their appliances. This includes oral–fungal infections, traumatic lesions, and alveolar bone loss, yet edentulous adults are less likely to see dentists than their dentate counterparts. Oral and pharyngeal cancers develop in both dentate and edentate older adults, especially individuals with long-term alcohol and tobacco use, and regular cancer screening examinations are essential to diagnose and treat these tumors at early stages. Therefore, adequate oral health care for the elderly people should include preventive dental treatment and increased availability and use of dental health services. Most oral diseases are preventable and treatable at every age.

Accordingly, physicians, nurses, and aides who care for older patients need either to recruit dental expertise routinely as part of the overall assessment or to familiarize themselves with the appearance of oral health and disease states. Patient well-being is optimized when nondentists detect oral disease and recommend preventive and interventive services. Similarly, dentists should refer patients to physicians for previously undiscovered or inadequately controlled medical problems (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease). Communication is critical between dental and medical practitioners regarding medically complex patients who may need individualized health care planning to maintain oral health at minimal risk.

This chapter focuses on specific oral tissues and their functions. It summarizes “normal” oral physiologic status in older adults and explains how common systemic diseases and their treatments may affect the oral tissues during aging (Table 42-3). It also briefly reviews the evaluation and management of oral disorders frequently encountered in the elderly population. Additional information on the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders is available in several comprehensive reviews cited in the reference section.

PROCESS | HEALTHY OLDER ADULTS | MEDICALLY COMPLEX OLDER ADULTS |

|---|---|---|

Taste | Unaffected | Diminished |

Smell | Diminished | Diminished |

Food enjoyment | Unaffected | Diminished |

Salivary output | Unaffected | Diminished |

Chewing efficiency | Slightly diminished | Diminished |

Swallowing | Slightly diminished | Diminished |

Dentition

The loss of teeth has long been associated with aging. National health surveys in demonstrate that approximately one-third of Americans older than age 65 years are edentulous. Although the prevalence of edentulous adults has decreased dramatically over the past 50 years, the population older than age 65 years still has an average of 11 missing teeth. Advances in dental treatment, disease prevention, increased availability of dental care, and improved awareness of dental needs have resulted in significant gains in dental health.

Tooth loss is attributed to two major processes: dental caries (discussed below) and periodontal diseases (discussed in the next section). Caries affects the exposed dental surfaces, and periodontal diseases are confined to the supporting bony and ligamentous dental structures. With the current trends toward increasing tooth retention in aging populations, there is a correspondingly greater risk for the development of both of these disease entities.

A tooth consists of several mineralized and nonmineralized components supported by the periodontal ligament and the alveolar bone (Figure 42-1). The outer dental structure is enamel and is the hardest, most mineralized component, consisting of ∼90% hydroxyapatite. Enamel covers the coronal aspect of the tooth and is the first hard tissue exposed to caries-causing bacteria. Dentin constitutes the main portion of the tooth structure, extending almost the entire length of a tooth. It is covered by enamel on the crown and by cementum on the root. Cementum is the least mineralized of the three components (50%) and is the component most susceptible to caries-causing bacteria. The central, nonmineralized portion is the dental pulp, which houses the vascular, lymphatic, and neuronal supply to the tooth.

Tooth loss in children and young adults is caused predominantly by dental caries, whereas in middle-aged and older adults, periodontal diseases play a greater role in the loss of teeth. Longitudinal studies of generally healthy adult males have found that the principal cause of tooth extraction is dental caries. Furthermore, caries activity continues throughout life and is not a phenomenon confined to any single period.

There are two classifications of dental caries, depending on the dental surface affected. Coronal caries is characteristic of caries in young adults and children. This occurs when the enamel and dentin of the coronal portion of the tooth are affected. In older adults, if gingival recession or periodontal disease causes the root surfaces of the tooth to become exposed to the oral environment, root surface or cervical caries may occur.

The primary caries-causing microorganism is Streptococcus mutans; oral Streptococcus, Actinomyces, and Lactobacillus organisms are also associated with coronal and root surface lesions. These bacteria reside on the tooth surface in dental plaque, a soft, firmly adherent mass that contains bacteria, food debris, desquamated cells, and bacterial products. Acid production by plaque bacteria dissolves the mineral content of the enamel, dentin, or cementum. The exposed protein constituents are destroyed by hydrolytic enzymes, and caries results. Dental plaque is considered a primary etiologic factor in dental caries, as well as a principal source of pathogenic organisms in periodontal diseases.

As a dentate individual gets older, there is susceptibility to coronal caries as a result of recurrent decay around existing restored surfaces, and the prevalence of root surfaces caries increases. For example, there is an 18-fold increase in the average number of tooth surfaces with root caries between persons aged 20 years and those aged 64 years (thus root caries often begins well before old age). There are many risk indicators for root surface caries: increased age, decreased exposure to fluoride, coronal caries, periodontal attachment loss, diminished oral–motor skills required for proper oral hygiene, and additional medical, behavioral, and social factors.

Studies in the United States reveal an increase in the mean number of decayed and restored teeth among older-aged dentate adults over the last 50 years. These trends probably reflect the increased retention of the natural dentition and a greater use of dental services by older adults; it is unlikely that they represent a true increase in dental caries activity. However, epidemiologic projections suggest that significant increases in the prevalence of root surface caries will occur in aging populations in the future.

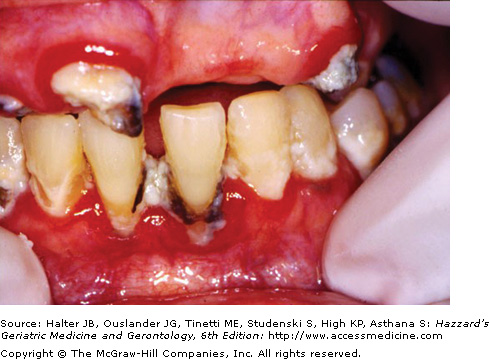

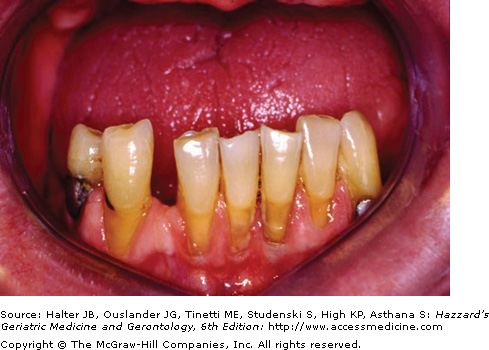

For an older person with teeth, caries is a significant concern and may be a source of pain, infection, and malnutrition. Dental caries will appear as darkish lesions that frequently are associated with dental plaque (Figure 42-2). Long-standing caries ultimately results in the destruction of the tooth with the possibility of a disseminated infection to the maxillofacial tissues and ultimately into the systemic circulation (septicemia). Once teeth have been destroyed from dental caries or periodontal disease, mastication, phonation, and deglutition may be perturbed. Also, social contact and nutritional status may be affected in a substantially edentulous aging individual.

The prevention of dental caries in an older adult is no different from that in a younger individual: fluoride, daily effective oral hygiene, and regular visits to dental professionals. Adult tooth surfaces can become resistant to decalcification and decay through repeated exposure to fluoride in water supplies, toothpaste, rinses, and gels. However, even resistant tooth surfaces can become carious when oral hygiene is inadequate and the mouth is exposed repeatedly to fermentable carbohydrates. When detected early, caries can be debrided from a tooth, and the missing tooth structure can be restored with a wear-resistant, insoluble restorative material (e.g., amalgam or composite resin). Some restorative materials contain fluoride (glass ionomer cements) and can help reduce caries risk. Untreated dental caries, however, in most circumstances progress to severe or even total loss of tooth structure and possibly pain, abscess formation, cellulitis, and bacteremia. Replacements for lost teeth are available with removable prostheses (partial dentures) or fixed prosthodontic appliances (crowns, bridges, implants).

Periodontium

The periodontium consists of the tissues that invest and support the tooth. It is divided into the gingival unit (gums) and the attachment apparatus (cementum, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bony process) (see Figure 42-1). Gingivitis occurs when the gingival unit is inflamed. Periodontitis (or periodontal disease) exists when there is inflammation and an appreciable loss of the attachment apparatus as a result of the presence of pathogenic microorganisms. Microbial species (e.g., Bacteroides, Fusobacterium, Prevotella, Actinobacillus, Capnocytophaga, Streptococcus) cross the gingival epithelium and enter subepithelial tissues, where they activate specific host defense mechanisms. Eventually, this causes tissue destruction, including bone loss and tooth morbidity.

Certain periodontal changes occur in aging individuals. For example, cross-sectional studies demonstrate that older adults show an increase in dental plaque, calculus (calcified dental plaque), and the frequency of bleeding gingival tissues. Older persons also experience greater gingival recession and loss of periodontal attachment (Figure 42-3). Longitudinal studies report that periodontitis is more prevalent and usually more extensive among black people, subjects with less education, those who have not seen a dentist recently, and those with gingivitis and certain pathogenic organisms. Currently, it is believed that periodontal disease proceeds through a series of episodic attacks rather than occurring as a slowly progressing continuous process. Furthermore, periodontal bone destruction results from an overly aggressive local immune reaction to the pathogenic organisms, triggering a cascade of cytokine and immunological events that can produce irreversible loss of alveolar bone. It is not known whether older age cohorts are more susceptible to periodontal destruction than are younger populations. Among healthy adults, periodontal attachment loss occurs at small increments in all age cohorts and does not occur in greater amounts in older healthy adults. However, many systemic diseases and therapeutic regimens commonly found in older individuals may affect adversely periodontal health. Therefore, an older medically compromised adult is especially susceptible to developing periodontal diseases and is at risk for associated dental–alveolar infections, pain, and tooth loss.