© Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015

Adam I. Riker (ed.)Breast Disease10.1007/978-1-4939-1145-5_1616. Operative Management of Metastatic Breast Cancer

(1)

Department of Surgery, Health Sciences Center – South, West Virginia University School of Medicine, 1 Medical Center Drive, 9238, Morgantown, WV 26506, USA

Keywords

metastaticbreast cancerlung metastasisliver metastasisbrain metastasishematopoietic stem cellschest wall controlsurgeryIntroduction

Worldwide, breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in women. The World Health Organization estimates 1.67 million new cases of breast cancer and 521,818 deaths from the disease in 2012 [1]. The worldwide incidence of breast cancer is increasing as life expectancy lengthens and as non-western societies adopt the lifestyle practices of western society [2]. In the United States, the American Cancer Society estimates 234,580 new breast cancers will be diagnosed and 40,030 deaths will occur in 2013. For women, a new diagnosis of breast cancer in 2013 will represent 29 % of all malignancies diagnosed [3]. Despite the increase in incidence, breast cancer-related mortality has shown a steady decline over the last decade [4]. The decline in mortality can primarily be attributed to two factors: the first is a better understanding of and adherence to screening guidelines, and the second is the advances made in the systemic treatment of breast cancer patients.

The most important predictor of survival is the stage of disease at the time of diagnosis. The American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) staging of breast cancer includes the size of the tumor at diagnosis (in centimeters), how many lymph nodes are involved, and if there is metastatic spread. Staging for breast cancer ranges from Stage 0 when the diagnosis is ductal carcinoma in situ to Stage 4 when there is disease distant from the breast or regional lymph nodes. Survival estimates from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) illustrate the need to diagnose the disease in the earlier stages, if possible, as the 5-year overall survival for localized breast cancer is 98.4 %. Patients diagnosed with early-stage disease comprise approximately 60 % of the entire patient population. As the tumor spreads to the locoregional lymph nodes, the relative 5-year survival drops to 83.9 %. While the metastatic population represents only 5 % of newly diagnosed cancers, the 5-year overall survival drops dramatically to only 23.8 % [5]. By diagnosing women at an earlier stage, the disease can be treated with a curative intent. Once the patient is diagnosed with metastatic disease, treatment is designed to contain the disease and can no longer be considered as having a curative intent.

Metastatic spread of breast cancer is generally classified by the end organ affected. Solid organ metastases to the liver and lung have a better outcome when compared to those with brain metastasis, while those with bony metastasis seem to have the longest survival. The standard treatment of metastatic (Stage 4) breast cancer is palliative, with systemic treatment as the mainstay of therapy. In this situation, the primary breast cancer is most often left intact as the patient undergoes their systemic therapy. This principle is derived from the traditional belief that metastatic disease burden is the greatest predictor of survival, while the complete operative removal of the primary breast cancer seemingly has no impact upon overall survival.

The development of treatment algorithms for patients with metastatic disease has always focused upon the systemic treatment of breast cancer, reserving an operative approach with removal of the primary lesion only for palliation of uncontrolled or rapidly growing disease. Recently, several investigators have questioned the dogma of this approach, instead asking whether resection of the primary lesion (breast cancer and other tumor histologies) in the presence of known metastatic disease may be beneficial to the patient, possibly improving their overall survival. For example, the resection of a primary renal cell carcinoma improves the overall survival when compared to leaving the primary cancer intact and treating solely with chemotherapy [6]. Additionally, it is well known that maximal tumor debulking of ovarian cancer improves, though marginally, survival for women with metastatic ovarian cancer. The stem cell theory is well established in malignancies such as leukemia and has been postulated to have implications in metastatic breast cancer. In the normal setting, this is a line of cells that are self-renewing and are best exemplified by the hematopoietic system. Hematopoietic stem cells must continue to renew and differentiate to maintain hemostasis. There is now a rapidly growing body of work indicating the presence of cancer stem cells (csc) with the first clear delineation of their existence in leukemia cells [7]. Further work in solid tumor cells has been able to reproduce similar results. Of greatest interest is the potential for metastatic cancer stem cells. These cells seem to have unique properties allowing for honing on metastatic sites as well as resistance to chemotherapy and radiation therapy [8]. More specific to the metastatic spread of breast cancer, Al-Hajj et al. demonstrated the presence of a unique cell line in heterogeneous breast cancer in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency mice with a higher propensity to be tumorigenic. CD44 and CD24 are adhesion molecules, and in the work by Al-Hajj, CD44+/CD24− cell lines were tumorigenic; a similar pattern found in normal stem cells [9]. The source of such cancer stem cells is still not well understood. The following questions remain: Are the csc derived from the primary tumor or from the metastatic deposit? Is it the primary lesion or the metastasis seeding and reseeding metastatic lesions? Can removing the primary tumor not only reduce the disease burden but also the source of the cancer stem cells and thereby improve overall survival?

On these principles, Khan et al. have challenged the traditional secondary role of surgery in the newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer patient. Analysis of the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) from 1990 to 1993 indicated approximately 57 % of metastatic breast cancer patients received either a partial mastectomy or a total mastectomy. Despite their diagnosis of metastatic disease, those who did have negative surgical margins had an improvement in their 3-year survival [10]. In this chapter, we will analyze the role of resecting the primary breast cancer and the distant metastatic sites, by reviewing the recent literature for trends in the overall outcome of Stage 4 patients.

Resection of the Primary Breast Tumor

The inclusion of surgical intervention in the treatment plan of patients with metastatic breast cancer remains somewhat controversial, with several investigators questioning the utility of an operative approach in a traditionally palliative treatment plan. The 2002 paper by Khan et al. examined the NCDB database from 1990 to 1993, finding a total of 16,023 Stage 4 breast cancer patients with 9,162 undergoing either a partial or a total mastectomy as part of their treatment. This represented 57.2 % of the patient population. The median age was 62.5 years, and of the 9,162 undergoing operative intervention, 3,513 (38 %) had a partial mastectomy and 5,649 had a total mastectomy. The 3-year observed survival rate for the entire group of Stage 4 patients was 24.9 % with a mean survival duration of 19 months. Once restricted to patients having either a partial mastectomy or a total mastectomy, the mean survival duration increased to 26.9 months and 31.9 months, respectively. Similar increases in the 3-year observed survival were also noted with 17.3 % (no surgical intervention), 27.7 % (partial mastectomy), and 31.8 % (total mastectomy). Using the nonsurgical group as a reference, the hazard ratio (HR) of death was 0.88 in the partial mastectomy cohort and 0.74 in those undergoing a total mastectomy. One of the criticisms of this study, and others to follow, is the retrospective nature of the data. The authors admit there is no way to control for the biases that lead to the resection of the primary tumor [6].

In 2006, Rapiti et al. published a similar study using the Geneva Cancer Registry, examining a total of 300 metastatic breast cancer patients from 1977 to 1996. In this cohort, 127 of the 300 (42 %) women had surgical intervention, 40 patients had a partial mastectomy, and 87 patients had a total mastectomy. Negative margins were accomplished in 61 (48 %) patients, and margin status was unknown in 26 % of the population. They found that excision of the intact primary breast cancer in the face of known metastatic disease imparted an impressive 40 % risk reduction in death due to breast cancer. The 5-year breast cancer-specific survival was 27 % when negative margins were achieved and 16 % and 12 % when the margins were either positive or unknown, respectively. Those women who underwent a surgical resection, but had positive margins on the final pathology, did not have a significant difference in survival when compared to those without surgical intervention. The adjusted HR for the four groups of patients were 1.0 for the nonintervention group, 0.6 for the group with negative margins, 1.3 for positive margins, and 1.1 for the margin-unknown cohort of patients. In comparing the characteristics of the two patient cohorts, the surgical intervention group tended to be younger, treated in the private (vs. public) sector of their healthcare system, and had lower T- and N-stages (as defined by the AJCC standard staging practices for breast cancer) at initial diagnosis.

Additionally, in the Rapiti et al. analysis, 61 % of the patients who had resection had only one site of metastasis, while 41 % of the patients who did not have an operation had one metastatic site of disease. A smaller proportion of the operative group had visceral metastasis (43 %) as compared to the inoperative group (58 %). Thus, the authors conclude that the complete resection of the primary tumor improves the long-term survival in women with metastatic breast cancer [11]. When interpreting these results, it is important to recognize the role of selection bias in the sample. The younger age and less distant disease burden at the time of surgical intervention may have contributed to the differences in the improved overall survival in those undergoing operative intervention compared to those who did not.

Finally, in 2007, Gnerlich et al. looked at the data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. The SEER program began collecting data in 1973, initially collecting just a series of small datasets. It has now become the largest inclusive dataset in the United States, comprised of over 22 population-based cancer registries and encompassing approximately 28 % of the entire US population [12]. Gnerlich and colleagues analyzed data from SEER datasets between 1988 and 2003, identifying 9,734 patients with Stage 4 breast cancer. Definitive operative intervention to remove the primary breast cancer in the face of known metastatic disease occurred in 47 % (4,578) of the women. Simple mastectomy was performed on 2,485 (54.3 %) patients, and 7,844 (40.3 %) had a partial mastectomy.

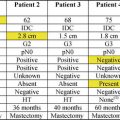

As in the study by Rapiti and colleagues, the women who had surgery were younger (age 62 vs. 66 p < 0.001) with smaller tumors that were grade 3 and estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) positive. The authors also noted that if the patients were Caucasian, married, or diagnosed earlier in the study period, they were more likely to have surgery compared to others. To control for such confounders, they developed six multivariate Cox regression models that were applied to the dataset. Utilizing the most conservative estimates of the relationship between surgery and survival, the data indicates that women who underwent an operation had a 37 % reduced risk of dying during the study period [13].

In addition to the large population-based studies, several smaller single-institutional, retrospective studies have indicated a survival benefit with extirpation of the primary breast tumor in the setting of metastatic disease. A study by Babiera et al. looked at 224 patients treated at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. They found that 82 (37 %) of the women with Stage 4 breast cancer underwent an operation (48 % had a partial mastectomy, 52 % had a total mastectomy). Twenty-nine of the 82 had an excisional biopsy, 41 had definitive treatment, and only seven had an operation for palliation of their symptoms. Again, it was found that women who were treated operatively tended to be younger in age, have a lower N-stage, have only a single site of metastatic disease, have liver metastases, have amplification of the Her-2/neu receptor, and have neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Only 14 (17 %) of the patients who underwent operative intervention had multiple metastatic sites, whereas 40 of the 142 (28 %) of the nonoperative group had multiple metastatic sites. With a median follow-up time of 32 months, the study demonstrated a trend toward an overall survival benefit to surgical resection of the primary tumor. The authors were able to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in metastatic progression-free survival for those in the surgical group with an HR of 0.54 (p = 0.0007). There was a trend toward an overall survival benefit on univariant analysis that did not reach statistical significance [14].

With the growing amount of data demonstrating a possible overall and progression-free survival benefit with resection of the primary tumor in the face of metastatic disease, Rao et al. analyzed patients treated at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center with metastatic breast cancer. They identified a study population of 75 patients and further classified them based upon the time to surgical resection from the time of their original diagnosis. They were divided into three groups: surgical resection at 0–2.9 months, 3–8.9 months, and at 9 months or more after diagnosis. During the time of the study period, from 1997 to 2002, most of the patients had an excisional biopsy to diagnose their disease (37 of 75 patients) resulting in a higher rate of incomplete resection due to the higher positive margin rate in this cohort. Forty-one underwent an operation with a curative intent and seven for palliation. The authors reported that those patients who had an operation ≥3 months after diagnosis had a better metastatic progression-free survival compared to those who were operated on within the first 3 months of their diagnosis but were not able to demonstrate a difference in overall survival. On univariant analysis, the size of the tumor, method of diagnosis, number of distant metastatic sites, and type of axillary surgery were all associated with an improvement in overall and progression-free survival. However, on multivariant analysis, only the patient’s race (Caucasian), fewer metastatic sites, and negative margins had better metastatic progression-free survival.

It was noted by the authors that most of the patients in the first group (surgery prior to 3 months from diagnosis) had an operation for purely diagnostic purposes and less for curative intent and, as expected, had a much higher rate of positive surgical margins. Additionally, they noted that those undergoing surgery at 3 months or greater had likely finished a chemotherapy regimen as their first-line treatment. Therefore, these patients were more likely to have had a response to systemic treatment, thereby highlighting the inherent selection biases of the retrospective study. The study authors recommend patients who have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis to undergo systemic therapy as a first-line treatment followed by a surgical intervention, with the goal of obtaining negative margins as these patients had an improvement in the metastatic progression-free survival without an impact on overall survival [15].

It is important to understand that breast cancer represents a markedly heterogeneous group of tumors, highly variable in both genotypic and phenotypic expressions. Such heterogeneity is highly variable between any two patients, and as such, differences seen in overall survival may be impacted by any number of factors. Extensive research has been performed in order to classify various breast cancers based upon their molecular classification, finding four major breast cancer subtypes: luminal A, luminal B, Her-2/neu positive, and basal-like. Luminal A breast cancers are strongly ER and/or PR positive and Her-2/neu negative with a low Ki67 and have the best overall survival. Luminal B cancers are ER and/or PR positive and Her-2/neu positive with a high Ki67 and comprise about 20 % of the tumors diagnosed. The so-called basal-like cancers are negative for all three markers, ER, PR, and Her-2/neu, and, as such, have the worst overall survival. The final subtype is ER/PR negative and Her-2/neu positive [16]. The most common of the subtypes are the luminal breast cancers (A and B), comprising approximately two-thirds of all breast cancers. Breast cancers with the ER-/PR-negative and Her-2/neu pattern are the second most common at approximately 20% of the population. The least common, basal-like, comprises only 10–15 % of the patient population, but these numbers vary with ethnicity. Basal-like breast cancers are more common in the Hispanic and Black patient population (16 % and 24 %, respectively) as compared to White patients (11.5 %) [17]. Acknowledging the impact of these subtypes of survival, Blanchard et al. investigated the role of the molecular classification of breast cancer and their influences upon the overall survival and metastatic progression-free survival compared to historical data.

The authors identified 16,401 patients in the database of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio who had hormone receptor assays performed. Of those patients, 807 had Stage 4 metastatic breast cancer at presentation, and in contrast to the previously discussed papers, the women receiving surgery in the study tended to be older, with an average age of 63.3 years as compared to 57.1 years in the nonoperative group. The patients in the study were more likely to be ER positive and PR negative and have T2 tumors at presentation, and the most common site of distant metastases was the bone. A total of 242 patients (61.3 %) underwent an operation with the majority of the patients undergoing a modified radical mastectomy.

In univariant analysis, significant improvement in overall survival was noted if the patients were ER positive, PR positive, or both ER and PR positive. ER-positive patients who underwent surgical intervention had a significantly improved overall survival as compared to those who did not have surgery (27.1 months vs. 16.8 months, p < 0.0001), and this was maintained in patients with ER-negative disease. On multivariate analysis, controlling for ER/PR, age, race, visceral metastases, number of metastatic sites, and histology, the surgical removal of the intact primary breast cancer in the face of metastatic disease remained an independent factor associated with improved overall survival. The authors also found that ER/PR receptor status and the total number of distant metastatic sites were independent factors; ER-/PR-positive patients and those with less metastatic sites had better overall survival. Using multivariate models, surgical intervention demonstrated an overall HR of 0.71. In subset analysis, the HR improved to 0.606 if the tumor was ER positive, but when patients had more than one metastatic site, the HR was 1.268. The group also looked at the survival differences based on site of metastases and found survival to be worse if the patient had visceral metastases or more than one site of metastatic disease [18].

Using the clinical database from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Massachusetts General Hospital, Bafford et al. examined 147 patients diagnosed with synchronous primary and metastatic breast cancer, of which 41 % underwent removal of the primary lesion. Interestingly, by examining the timing of their diagnosis as either preoperative or postoperative, they found that only 25/147 (17 %) patients were diagnosed with metastatic disease prior to their surgical intervention. There was no statistically significant difference in age, but patients receiving surgery were more likely to receive adjuvant radiation therapy and have fewer sites of distant disease. The authors further adjusted for ER and Her-2/neu receptor status, age, total number and location of metastases, and the various regimens of systemic therapy, finding that surgery was still a predictor of improved survival. The median overall survival, unadjusted, was 3.52 years in the surgical group versus 2.36 years in the nonsurgical group. Perhaps more important was the subset analysis of survival between those diagnosed before and after surgical intervention. For those patients who were diagnosed with metastatic disease prior to surgery, the overall survival was not impacted by surgical resection, and these patients had overall survival comparable to those who did not have surgical intervention at 2.4 years and 2.36 years, respectively [19].

In the Netherlands, Rashaan et al. accessed the database of two Dutch hospitals and identified 171 patients diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer between 1989 and 2009. Thirty-five percent of these patients had surgical intervention (59 of 171 patients) of whom 35 % (21 of 59 patients) were undiagnosed with metastatic disease at the time of their surgical intervention. The patients who had extirpation of their primary tumor were younger and had a lower T-stage, lower-grade tumors, and less comorbid conditions. In univariant analysis, there was an association between surgery and survival; however, this finding was not significant when examined by multivariate analysis.

The authors identified that patients who were younger at presentation and had an overall favorable health profile were operated on more frequently as a result, thus translating into a survival benefit with removal of the primary tumor. While a small patient population, and contrary to the aforementioned study by Bafford et al., they did not identify differences in outcomes between those who were operated on pre- and post-identification of metastatic disease. The authors again acknowledge the selection bias inherent in the retrospective nature of the study and recognize the need for a prospective randomized control trial to help reduce these confounders [20].

In a much larger study, Nguyen et al. identified 733 women with newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer in the British Columbia Cancer Agency (years 1996–2005). They analyzed tumor characteristics, overall survival, and locoregional progression-free survival and compared locoregional treatment to those who had no local treatment. Fifty-two percent (378 of 733) had locoregional intervention defined as surgery alone (67 %), radiation alone (22 %), or a combination of the two (11 %). Those who were less than 50 years of age and had better performance status, tumors <5 cm, and low nodal disease burden had a higher rate of locoregional intervention. Additionally, patients who had less than five metastatic lesions and/or were asymptomatic from their metastatic disease were also more likely to have locoregional treatment.

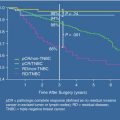

Eighty percent of those who underwent local intervention were diagnosed with metastatic disease prior to their intervention, and 20 % had distant disease diagnosed with 4 months of presentation and diagnosis. The authors found the overall survival rate and the locoregional progression-free survival were better for women who underwent locoregional treatment as compared to those who did not. The 5-year overall survival was 21 % for those who underwent local regional therapy as compared to 14 % in the group who did not (p < 0.001). Additionally, the local progression-free survival was 72 % in the regional therapy group and 46 % in those that did not (p < 0.001). Importantly, the type of locoregional therapy did not seem to play a role; it was merely that locoregional therapy had been provided. The improvement in overall survival was maintained upon multivariant analysis, with locoregional therapy associated with an improved overall survival and negative resection margins, receiving chemotherapy and hormonal therapy [21].

In 2008, Hazard et al. published a small, single-institution, retrospective review of 111 women treated at the Lynn Sage Breast Cancer Center at Northwestern University. The authors found that surgery alone did not improve overall survival, but gaining locoregional control of chest wall disease was associated with an improved overall survival. The authors determined the lack of chest wall disease, whether by surgery, radiation, systemic therapy, or any combination thereof, imparted an overall survival benefit to women diagnosed with metastatic disease. Of the 111 women included in the study, 103 had information regarding chest wall disease. Surgery was performed in 42 % of the patients, with successful chest wall control maintained in 82 % of those patients as compared to only 34 % who did not have surgical intervention. The overall hazard ratio associated with chest wall control was highly significant (p < 0.0002). Thus, the authors conclude that maintaining chest wall control, whether by surgery or not, may play a role in improving overall survival in women diagnosed with metastatic disease at presentation. The reason for this overall survival benefit is not well understood but may be related to the reduction in tumor volume and thus a potential for seeding and reseeding of metastatic sites. Again, the authors called for a randomized control trial to help discern the role locoregional intervention plays in overall survival and progression-free survival in metastatic breast cancer patients [22].

While all the previously referenced studies indicate a marginal benefit of locoregional therapy to the patient with metastatic breast cancer diagnosed at presentation, a study published in 2011 by Dominici et al. contradicts these findings. Using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Breast Cancer Outcomes Database, they looked at patients who were treated with surgical intervention prior to systemic treatment and compared them to women who received no surgical intervention. They matched the patients based on age, ER status, Her-2/neu status, and number of metastatic sites. A total of 1,048 patients with metastatic disease were identified, but the appropriate data was only available for 551 patients. The authors matched 236 patients without intervention to 54 patients with surgical intervention. They found the survival was similar between the two groups, 3.4 years in the nonsurgical versus 3.5 years in the surgical group [23].

Each of these studies provides a variation on the hypothesis that surgical intervention, or at least locoregional intervention, will help impart an overall survival benefit for patients diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. While it is easy to attribute all of the survival benefit to the selection bias inherent in retrospective studies, this may be underestimating the role primary tumor resection has on distant disease control. As our knowledge of cancer stem cells and other mechanisms of tumorigenesis improves, it is possible that reducing local disease burden with complete surgical resection, in and of itself, may play a key role in an improved overall survival. With a 5-year survival rate of less than 25 %, it behooves us to continue to strive to find ways of improving this relatively dismal prognosis. To this end, there is now one randomized controlled trial in the United States whose sole aim is to identify the possible role that surgery or locoregional treatment may play in improving the outcome in Stage 4 patients. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2108 study is a randomized phase III trial examining the value of early local therapy for the intact primary tumor in patients with metastatic breast cancer. All women enrolled in the trial will undergo induction systemic treatment after the diagnosis of metastatic disease is made. Patients may be enrolled either at the time of diagnosis or up to week 30 of systemic treatment. Systemic therapy is up to the provider, but the patient must have completed 16 weeks of therapy. Those who respond to treatment with either stable or decreased metastatic disease burden defined as (1) no new sites of disease, (2) no enlargement of existing disease ≥20 %, and (3) no deterioration of symptoms will be randomized into one of two arms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree