Fig. 19.1

Poor cosmetic outcome from conservation surgery for an inferiorly placed cancer resulting in a typical bird’s beak deformity

Fig. 19.2

Poor cosmetic outcome from conservation surgery for a superiorly placed tumour resulting in size and volume asymmetry and nipple malposition

There has been a rapid growth in the use of and interest in these techniques and a proliferation of methods available [1]. Complex atlases of procedures based on the site and size of the tumour are available to aid the surgeon in selecting the optimal technique [2]. The techniques are complex and require skill and training both in understanding their indication and contraindications and in their optimal performance surgically to get good results. In some centres, these procedures are performed jointly between breast oncology surgeons and plastic surgeons. In some centres, fully oncoplastic trained surgeons perform both the ablative and restorative components of surgery. Training in oncoplastic surgery is now more widely available, and good quality training programmes and guidelines are being developed globally to make these techniques more widely available and enhance quality [3–5].

19.2 Indications for Oncoplastic Surgery

- 1.

Adverse tumour volume to breast volume ratio .

Resection of more than 15–20% of breast volume is likely to result in asymmetry and adverse cosmetic outcomes (◘ Figs. 19.1 and 19.2) as was elegantly shown by the Nottingham group [6] with patient satisfaction rates of over 90% if only 5% or less of breast volume was excised to only 25% satisfied once 20% of breast volume is lost. Whilst this may be addressed by the use of neoadjuvant systemic therapy in some cases, in others, the use of oncoplastic techniques will permit higher percentage volume loss with good cosmesis and better patient satisfaction by reshaping the breast to minimise indentation and deformity.

- 2.

Adverse tumour location (superomedial, central/sub-areolar, inferior).

Some areas of the breast are more difficult to resect tissue from than others whilst maintaining good cosmesis. Areas of concern are medially located tumours where the scar or indentation may lie in the cleavage area and where there is less breast parenchymal volume and superiorly sited tumours for the same reason. Both sites may also result in nipple malposition due to scar retraction. Resection of inferiorly sited tumours may cause nipple malposition or a bird’s beak deformity. Centrally located tumours may necessitate loss of the nipple and, if resected as an ellipse, cause a flattened off breast shape. Oncoplastic techniques allow better cosmesis following resections in these areas. A disc of nipple skin may be imported to create a base for a nipple reconstruction for centrally located tumours.

- 3.

Redo conservation surgery.

This is a more controversial indication for oncoplastic surgery [7]. There is little good quality evidence at present in support of this, but for some women who have a strong preference for a conservative approach, oncoplastic operations may contribute to acceptable cosmetic results. Caution is needed in undertaking these procedures as these women will have had breast radiotherapy and may be at higher risk of wound healing problems and pedicle hypovascularity. The oncological safety of these procedures is also not supported by high-level evidence.

- 4.

Multifocal and multicentric disease.

There is emerging evidence that BCT in multifocal (MF) disease is oncologically safe [8] but may result in a slightly inferior outcome compared with BCT in unifocal breast cancer. Patients in the MF group had higher 10-year LRR however (0.6% vs. 6.1%, p < 0.001). Oncoplastic surgery may be used to perform segmentectomy in MF disease confined to one segment with subsequent reshaping of the breast. In multicentric disease, oncoplastic techniques may also be used to resect more than one discrete area in different breast quadrants whilst retaining breast shape; however, there is little high-level evidence supporting the oncological appropriateness of this approach at present although a number of case series show acceptable oncological outcomes [9, 10].

- 5.

Macromastia.

For women with pre-existing macromastia, oncoplastic surgery offers an opportunity to simultaneously perform bilateral breast reduction which may have considerable appeal for these women. Macromastia may cause shoulder and back pain, embarrassment, difficulty finding suitable clothes and problems with skin infections in the inframammary fold. For many of these women, bilateral breast reduction may have many benefits by reducing these symptoms, but also, women with large breasts may be technically challenging for the radiation oncologist to administer whole breast radiotherapy to and may also suffer more significant post-radiotherapy complications such as breast oedema and skin reactions. The majority of studies of therapeutic mammoplasty for macromastia achieve low rates of incomplete excisions (approximately 10%) [11]. The wide local excision is usually performed prior to, and as a separate specimen to, the reduction procedure; although the tumour is in one of the primary areas where tissue is excised as part of the reduction, the tumour may be excised en bloc with the reduction sample, but care must be taken with margin marking and orientation. Rates of local recurrence with this technique are acceptable [11].

A large review including data on 276 patients [12] treated with bilateral reduction mammaplasty concluded that women with breast cancer and macromastia can obtain oncologically safe and cosmetically excellent outcomes.

A detailed review [13] of the evidence about therapeutic mammaplasty (TM) concluded that the oncological outcomes appear comparable to simple BCS. However, they note that no randomised controlled trials have been performed and the evidence in support of these techniques is all derived from case series and cohort studies.

19.2.1 Oncological Safety of Oncoplastic Techniques

Due to the sometimes complex nature of such surgery, which may make margin assessment more challenging, complicate surgery to take cavity shaves and make breast radiotherapy boost more difficult to localise, concerns have been raised about whether these procedures are oncologically safe. Whilst there have been no randomised trials to compare the outcomes of standard BCS/mastectomy with oncoplastic surgery, there have been numerous large cohort studies, often with long follow-up reported, which show that these techniques can result in acceptable local regional recurrence rates [14–18]. Even in cases with large-sized primary tumours, acceptable rates of recurrence are reported [15]. A recent systematic review has confirmed this general finding [16].

Based on the fact that oncoplastic techniques generally have the flexibility to remove larger volumes of breast tissue [14], this should give the surgeon flexibility to take wider margins and hence enhance oncological safety. However, the often complex pattern of tissue removal and repositioning means great care is needed in orienting specimens and documenting and marking cavities.

Early in the oncoplastic era, small, retrospective and relatively short follow-up series were published presenting recurrence rates and/or survival rates. One such early series in 2003 presented 101 patients with a 16% re-excision or subsequent mastectomy rate, a LRR of 9.4% and an overall survival rate of 95.7% after 44 months of follow-up [14]. Whilst a 9.4% LRR is high by modern standards and was relatively high for that time subsequent series have shown much better results. For example, Rietjans and colleagues [18] in 2007 presented 148 cases with only a 2.2% re-excision/mastectomy rate, a 3% LRR and an overall survival rate of 92.4% after 74 months of follow-up. Numerous studies have now reported on oncoplastic BCS, and the results are generally very good and similar to standard oncology outcomes [14–18].

19.3 Achieving Clear Resection Margins in Oncoplastic Surgery

Whilst rates of local recurrence are falling steadily following BCS, when it does occur, it is distressing and may result in the need for mastectomy [19] and a slightly higher late mortality disadvantage. Rates are falling due to better adjuvant radiotherapy and systemic therapy regimes, coupled with better surgery and margin assessment by pathologists. However, wider margins are not the answer. Indeed recent evidence and consensus are that a no-tumour at the inked margin is acceptable [20] and wider margins than necessary adversely affect cosmesis. Reoperation for cavity re-excision also has an adverse cosmetic impact as well as the financial costs and personal burden to the patient. There are a range of techniques to ensure that adequate margins are achieved which have proven efficacy in reducing rates of positive margins, but detailed review is out of the scope of this chapter. Excellent reviews are available [21]. Use of these techniques is very relevant in the oncoplastic setting where it may be technically challenging to go back to re-excise a positive margin.

The tumour cavity surgical margins after an oncoplastic procedure may be altered or transferred from the primary tumour location to other quadrants in the breast due to the use of local or distant displacement/replacement flaps as it happens in lateral or J-mammaplasty or reduction mammaplasty techniques such as inverted T mammoplasty. It is therefore imperative that the surgeon keeps detailed notes and diagrams of the operation and marks the original tumour bed with clips and ideally, in complex cases, uses some form of intraoperative margin assessment to minimise the need to go back for cavity shaves. Good communication with the radiation oncologists is essential when boost is planned as the skin scar may be some distance from the tumour bed and use of marker clips to the tumour bed, before rotation/translocation of the tissue, is essential [22, 23]. Placement of six clips has been proposed as optimal (medial, lateral, superior and inferior and to mark the deep fascia and subcutaneous margins).

19.4 Specimen Marking

Specimen orientation in breast surgery is of paramount importance. This is more so in oncoplastic surgery where the specimens may be irregular and asymmetric due to tissue removal for reshaping of the breast in addition to the actual tumour specimen. In oncoplastic cases, the tumour is more likely to be complex: large, multifocal or multicentric tumours or a known area of impalpable DCIS adjacent to an invasive focus, all of which must be communicated to the pathologist. Some cases may have followed primary systemic therapy, and only a marker clip may indicate the original primary location. The pathologist must be made aware of these preoperative tumour characteristics to avoid missing known second lesions at specimen «cut up» which is vital for margin assessment. Specimen X-rays should be sent to the pathology lab, especially in cases with complex tumour patterns (e.g. DCIS extent). This may help the pathologist to locate an impalpable tumour in the specimen. Each margin must be specifically marked and a detailed diagram provided showing which marker indicates which margin in the event that re-excision is needed. This will ensure that only the involved margin needs to be re-excised rather than the entire cavity re-excision [24]. Any intraoperative cavity shaves must be similarly identified and the new cut surface marked. Despite the importance of specimen marking and orientation, there is no universally accepted and implemented specimen marking system. A recent survey in the UK [25] of 117 breast units, nearly one quarter had no specimen orientation protocols. Among these, 11 were national breast screening units.

In general, the surgeon places sutures or clips during surgery, and inking of the specimen margins is done later by the pathologist in the pathology laboratory [26]. However, there may be better re-excision rates if the orientation is done intraoperatively with sutures and ink applied by the surgeon in the presence of the pathologist [27]. There are also commercially available orientation boards/holders to which specimens may be pinned and orientated in some detail to facilitate both cut up and specimen radiology [25, 28–30]. The most common protocol seems to be the method with different length/number of sutures or clips on three of the six margins [25, 31]. However, the suture-only method may not facilitate optimal specimen orientation by the pathologist, especially in small specimens (smaller than 20 cm3), whilst the presence of the skin or muscle on the specimen does not contribute to better orientation [30].

19.5 Cavity Marking

Knowing the exact position of the tumour bed has always been a great help for the radiation oncologists to deliver boost radiotherapy to breast patients. Although there are no data to support that more accurate tumour bed delineation will lead to improvement of local control, it may very well improve cosmetic outcomes [32].

Delineation of the resection cavity by seroma formation or location of the skin incision is relatively largely inaccurate [32]. The best marking method is the placement of metallic clips to the tumour cavity varying from one clip (not very accurate) to six clips for each margin of the cavity and up to 8–10 surgical clips [33] into the tumour bed after resection and before oncoplastic reconstruction. Detailed notes should be kept of clip placement.

19.6 Oncoplastic Techniques: Classification

19.6.1 Volume Replacement, Volume Displacement, Level 1 and 2

There are two broad techniques in oncoplastic surgery to reconstruct the breast parenchymal defect:

- 1.

Volume displacement: Local breast parenchyma is repositioned to fill the defect using either simple advancement or more complex pedicles (levels 1 and 2, respectively).

- 2.

19.6.2 Volume Displacement

Local breast parenchymal rotation flaps can only be used in breast conservation surgery. There are several options from small parenchymal rotations after lumpectomy and semicircular incisions up to complex breast reduction techniques, nipple transposition and local skin rotation flaps. These techniques may be divided into level 1 and 2 depending on whether a formal pedicle is used. There are a variety «atlases» of techniques for tumours in different breast quadrants [2], and surgeons should be familiar with a range of methods for each site as well as having an understanding of how they may need to be modified in certain circumstances (◘ Fig. 19.3).

Fig. 19.3

Atlas of techniques of oncoplastic reshaping according to the quadrant of the breast containing the cancer

19.6.3 Technical Atlas of Level 1 Techniques

All types of breast defect reconstructions using local breast tissue without the use of breast reduction techniques or major nipple transposition belong to level 1 techniques (◘ Fig. 19.4a–f). Typical level 1 techniques include batwing flaps (◘ Figs. 19.5 and 19.6) and round block and doughnut techniques (◘ Fig. 19.7a–f). Also intra-parenchymal flaps using dual-layer undermining (between the pectoralis and its fascia as well as between the skin and breast gland to rotate the breast parenchyma into the defect and close it) are level 1 techniques. In general, these techniques are best performed on women with dense breasts, especially if significant parenchymal flap mobilisation is used. Women with fatty breast may be at increased risk of fat necrosis.

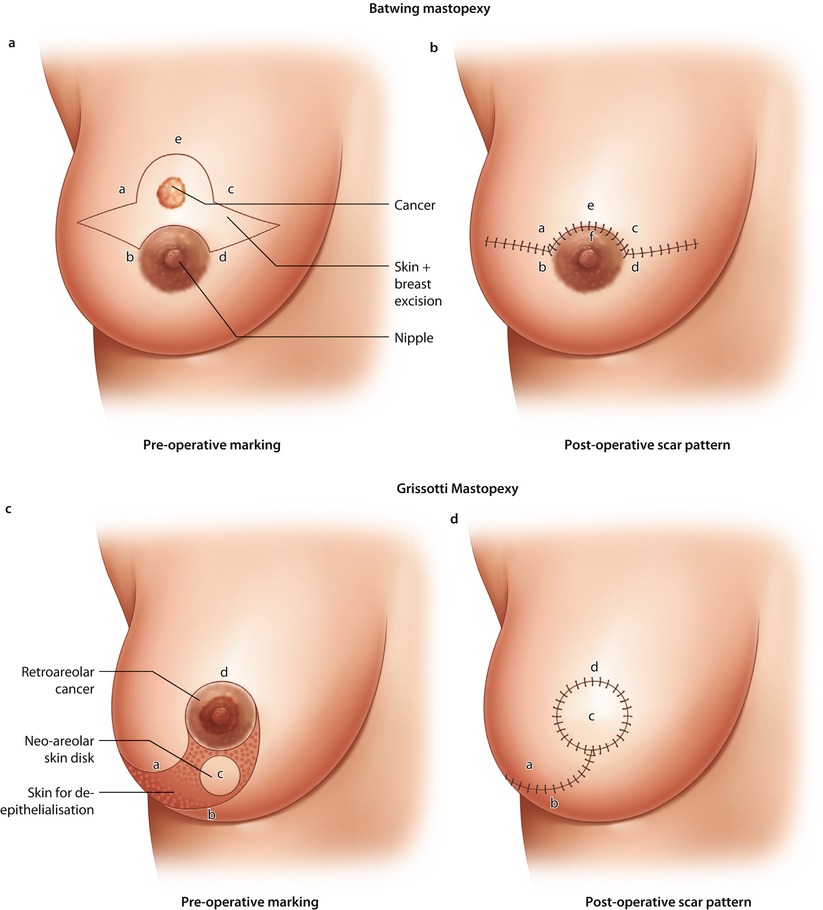

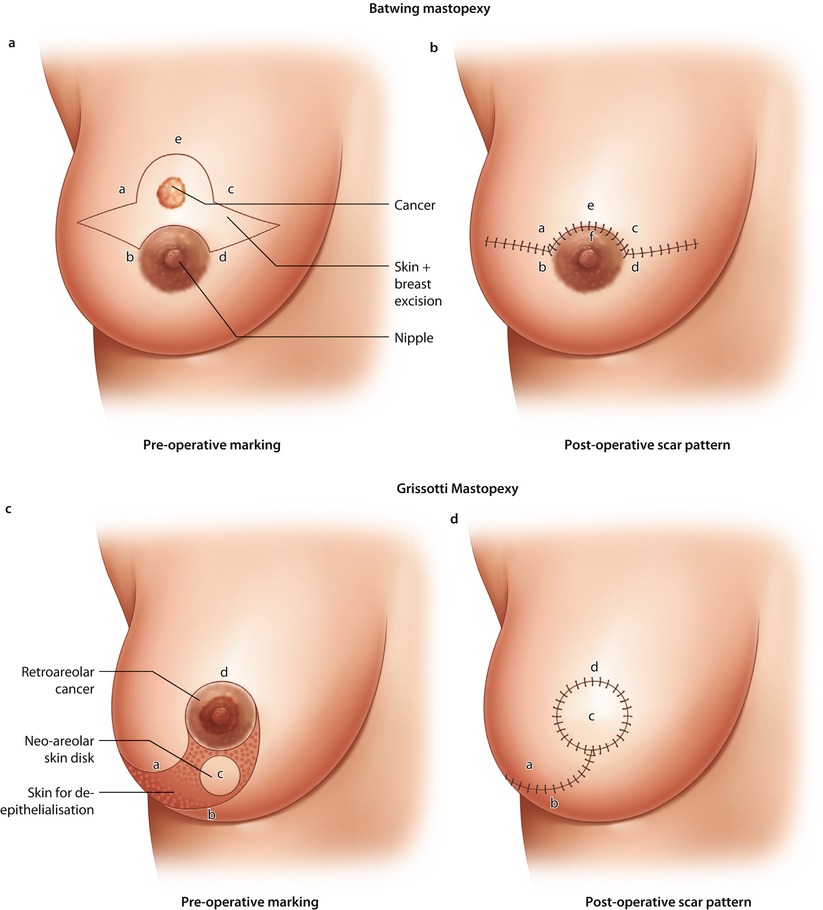

Fig. 19.4

Batwing mastopexy. a Preoperative marking. b Post-operative scar pattern. Grisotti mastopexy. c Preoperative marking. d Post-operative scar pattern. Doughnut mastopexy. e Preoperative marking. f Post-operative scar pattern, Sutures in parenchyma to close defect

Fig. 19.5

Preoperative marking of a batwing mastopexy for a tumour located in the 12.00 position

Fig. 19.6

Post-operative outcome of a batwing mastopexy for a tumour located in the 12.00 position

Fig. 19.7

Flattening of the breast mound due to higher-volume resection with a batwing mammoplasty

19.6.4 The Batwing Mastopexy

The batwing technique derives its name from the shape of the incision. In general, this technique is ideal in cases of breast tumours close to the skin behind or just above the nipple. In these cases, it is necessary to resect the skin together with the tumour. The resected skin with its underlying defect may easily be filled with the tissue located caudally from the breast tumour (Figs. ◘ 19.4a, b, ◘ 19.5, and ◘ 19.6). Women with ptotic as well as non-ptotic and smaller breasts are ideal candidates for batwing procedures. The technique has a very low morbidity as the nipple retains most of its attachments and vascular supply with very little parenchymal undermining, so there is little risk of fat necrosis. If the resection volume is too large, the resultant breast shape may be somewhat flattened (◘ Fig. 19.7). Larger defects above 20% of breast volume are not suitable for this technique. Cosmetic outcomes are generally very positive [34].

19.6.5 Doughnut Mastopexy

The doughnut technique is based on a circum-areolar incision and de-epithelialisation of the epidermis around the nipple-areola complex. The diameter of the de-epithelialised area may be chosen based on the planned resection volume and breast size. Breast tumours in any location, even behind the nipple, may be resected with this technique. It is an appropriate technique for smaller- to medium-sized breasts and more peripherally located breast tumours. Morbidity is low and cosmesis is usually excellent with a periareolar scar (◘ Fig. 19.8a–f). The size of the areola may change after surgery and may necessitate contralateral adjustment. The doughnut technique is easy to learn and has a very low morbidity rate.

Fig. 19.8

Stages of a doughnut mastopexy procedure. a Marking up. b De-epithelialisation. c Resection of tumour. d Mobilisation of breast parenchyma to fill defect. e Suture of the skin to tighten skin envelope. f Early post-operative result

19.6.6 Round Block Mastopexy

A modification of the doughnut technique is the round block technique. Without de-epithelialisation, the nipple-areola complex is circumcised completely, and the breast tissue is separated from the skin above the tumour (◘ Fig. 19.9a–d) [35]. The round block must not be used for centrally located tumours. It gives similarly excellent results to the doughnut technique.

Fig. 19.9

Stages of a round block technique. a Full circumcision of the areolar and access to the breast parenchyma for tumour resection. b Parenchymal mobilisation to close the defect. c Skin closure. d Early post-operative result

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree