CHAPTER 12 Nutritional Epidemiology and Nutritional Assessment

12.1 EPIDEMIOLOGY

By the end of this section you should be able to:

• define nutritional epidemiology

• summarize its aims and limitations

• outline the concepts of population, exposure, outcome and epidemiological effect

• define validity and repeatability

• interpret results of a study taking into account possible effects of bias, chance and confounding, and the question of generalizability

• summarize criteria for assessing evidence of causality

• explain the main features of different epidemiological study designs, including their strengths and weaknesses

Introduction to the science of epidemiology

In public health and health promotion, epidemiology is important both to provide knowledge for action and to evaluate the effect of interventions. This chapter describes the basic concepts of epidemiology, important aspects to consider when interpreting results, and the most common study types – with examples from nutritional epidemiology.

Important concepts in epidemiology

The outcome

• Incidence is defined as the number of new cases appearing in the study population during a specified period of time. If a population of 100,000 people saw 190 cancer cases over a period of one year, the cancer incidence would be 0.0019 per person year, or 1.9 cancer cases per 1000 person years.

• Prevalence is the proportion of a population that is cases at a given point in time. It is a paradox that efforts to improve the survival of those with a disease without curing it will increase the prevalence.

Mortality rates are a special form of incidence rates – the incidence of death – and can have different forms: crude mortality rates relate to the population as a whole. Mortality rates for specific groups, most commonly by gender and age, contribute to a better understanding of death rates. Box 12.1 provides definitions of these terms.

The exposure

Many diseases, such as coronary heart diseases and cancer, have a long lag between the onset of the relevant exposure to manifest stages of the disease. This is called the latency period. The relevant dietary exposure affecting the risk of developing cancer may therefore be 10–20 years before the cancer is diagnosed. Without historical data on past exposures, it is sometimes assumed that measurements at a later period may serve as reasonable alternatives, and if dietary habits are stable over time present food intakes certainly can give some indication of intakes in the past. Recall of past exposures is often problematical and so measurements of current exposures are preferred as they are much more amenable to quality control.

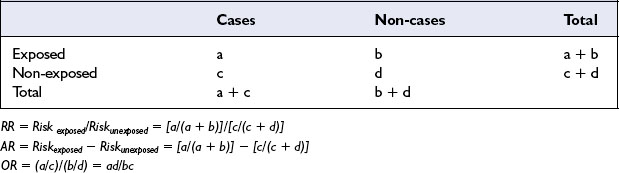

Measures of association and effect

The odds ratio (abbreviated OR) is an alternative to relative risk. The term odds refers to probability based on a ratio rather than a proportion. An example is obesity (the exposure) and gestational diabetes (the outcome). If 50 of 100 women with gestational diabetes were obese the odds of obesity among the diabetics are 50:50 (odds = 1), while if 20 of 100 non-diabetics were obese the odds of obesity among the non-diabetics are 20:80 (odds = 0.25). The odds ratio is calculated by dividing the odds of exposure among the cases by the odds of exposure in the non-cases, here:

The odds of being obese among the women with gestational diabetes are therefore four times greater than among the healthy women (see Table 12.1).

Interpretation of results

Bias

For example a group of people is invited to participate, but only a subset is willing to take part. Participants who volunteer to take part in studies are likely to be more educated and health conscious than the general population and therefore not fully representative of the study population – the results may misrepresent the true disease burden. An example of information bias is that obese subjects tend to underestimate their energy intake more than non-obese subjects do, and so self-reports of diet in a study of obesity are likely to be biased.

Causality

• Specificity (ie one particular exposure always should lead to a specific disease but this criterion is probably less relevant as many diseases have multiple causes and some factors contribute to more than one condition)

• Temporal sequence of cause and effect

• Biological gradient (where the risk increases or decreases progressively with higher exposure)

• Biological plausibility and coherence

• Experiment (reversibility) (when reducing a factor that increases the disease risk gives a corresponding drop in disease risk)

Epidemiological studies have contributed considerably to present scientific understanding of the relationships between dietary habits, social factors (including cultural and psychological determinants), and health. The failure to demonstrate associations between diet and disease may in many instances be due to the imprecision of the measures of diet rather than to the absence of an association.

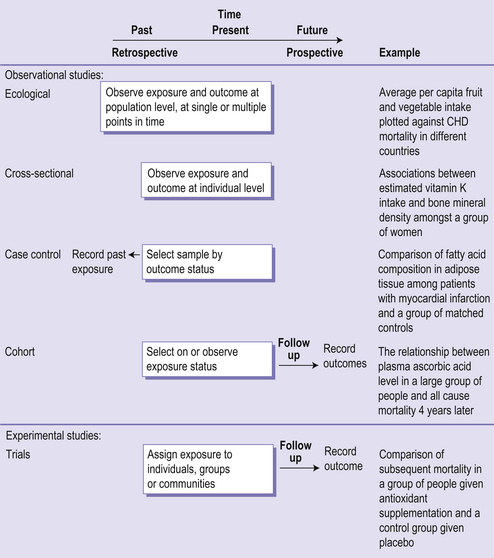

Epidemiological study designs

Figure 12.1 gives a schematic overview of the main study designs. Study designs differ according to whether the researchers observe natural processes (observational studies) or are attempting to influence the exposure (experimental studies), and according to the time order of collecting information in exposure and outcome, either at the same time or with a time difference.

Observational study designs

• Ecological studies in which the exposure and outcome measures are matched at a group or population level instead of at the individual level, either between populations or in the same population compared over time.

• Cross-sectional studies in which both the outcome and exposure status are determined simultaneously, and so it is impossible to distinguish if one appeared before the other. For example if it is found that people with high blood cholesterol eat more low fat foods than the general population, this may be due to a dietary change following diagnosis.

• Case-control studies in which patients that have developed a specific disease or condition (the cases) are compared with healthy controls who are representative of the population these cases come from (the controls).

• Cohort studies in which a group of people is followed over time to record which individuals develop the outcome of interest, usually a disease or a cause-specific death.

Experimental study designs

• Randomized controlled trials assess the effects of an intervention or treatment by comparing it with an established treatment or placebo (inactive treatment).

• Community intervention studies with interventions designed to promote health at the community level, using mass media, supermarkets, workplaces or other settings believed to offer cost-effective means of influencing population behaviour. Such intervention studies may involve a control group, or consist of an uncontrolled before-and-after design.

Systematic reviews

With the ever-increasing flow of newly published articles, gathering and evaluating the evidence is a massive task for any researcher, not to mention health practitioners. Systematic reviews summarize the results of similar studies. Meta-analysis is a sub-category of systematic reviews. Results from several independent studies are combined and analysed. When meta-analyses are well conducted, they provide an unbiased and more precise estimate of the effect of interest. The Cochrane Collaboration (http://www.cochrane.org/) was founded in 1993 with an aim ‘to help people make well-informed decisions about health care by preparing, maintaining and ensuring accessibility to systematic reviews’. The main emphasis of the Cochrane Collaboration is on the effects of health care interventions.

Nutritional epidemiology

Diet is not a simple behavioural variable such as smoking, but a series of variables, including nutrients, non-nutrients, single food items and food groups. Recently, increased attention has also been given to physical characteristics of a food, meal composition and food patterns, just adding to this list of exposure variables to consider. Dietary variables are also very challenging to analyse because these are strongly correlated; for instance, persons with a high intake of vitamin C often also have high intakes of fibre, β-carotene and other antioxidants. This is because foods rich in one nutrient may be rich in other nutrients.

• Population is the population of interest for a particular study question

• Outcome is the disease or health-related variable being studied

• Exposure is any factor that may influence the risk of the outcome

• Measure of association and effect is the quantified relationship between exposure and outcome

• Validity is the degree to which a measurement assesses the aspect it is intended to measure

• Reproducibility is the degree to which a measurement produces the same result when used repeatedly under given conditions

• An observed exposure–outcome association can be due to four factors: bias, chance, confounding or a true causal relationship

• Bias – systematic deviation of results from the truth – takes two main forms: selection bias (related to the sample) and information bias (related to the data)

• Chance – random variation may produce a plausible or implausible finding

• Confounding – confusion between two processes – may distort study findings

• Causality can rarely be proven, but if bias, chance and confounding have been considered and the Hill criteria are broadly met, then causal inference is appropriate

• The essential question a study seeks to answer guides the decisions regarding the study sample, how exposure and outcome are measured and the preferred study design

• The external validity (generalizability) of a study depends on its design and execution

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree