Peripheral blood cells

Normal peripheral blood contains mature cells that do not undergo further division. Their numbers are counted by automatic cell counters which also determine red cell size and haemoglobin content.

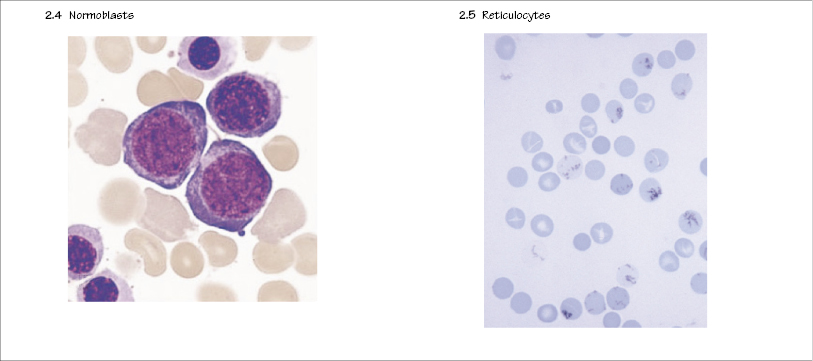

Red cells (erythrocytes)

Red cells are the most numerous of the peripheral blood cells (1012/L) (Fig. 2.1). They are among the simplest of cells in vertebrates and are highly specialized for their function, which is to carry oxygen to all parts of the body and to return carbon dioxide to the lungs. Red cells exist only within the circulation – unlike many types of white blood cells they cannot traverse the endothelial membrane. They are larger than the diameter of the capillaries in the microcirculation. This requires them to have a flexible membrane.

Haemoglobin

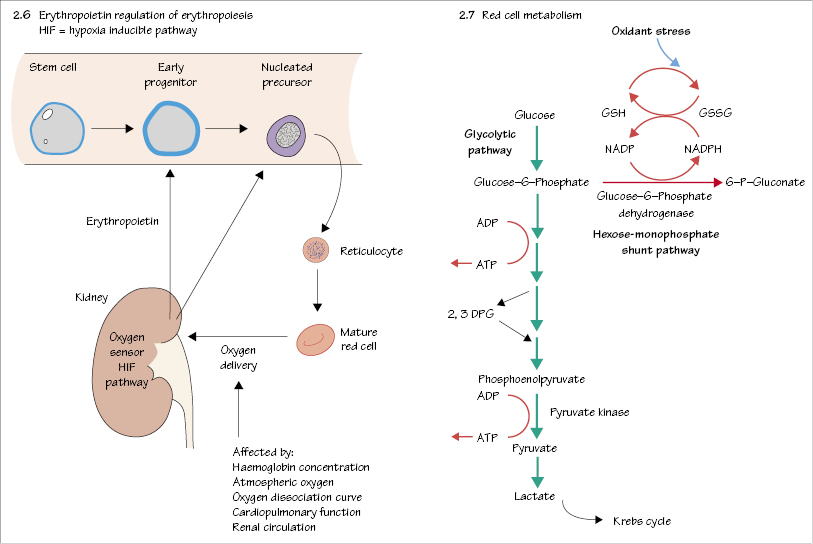

Red cells contain haemoglobin which allows them to carry oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2). Haemoglobin is composed of four polypeptide globin chains each with an iron containing haem molecule (Fig. 2.2). Three types of haemoglobin occur in normal adult blood: haemoglobin A, A2 and F (Table 2.1). The ability of haemoglobin to bind O2 is measured as the haemoglobin–O2 dissociation curve. Raised concentrations of 2,3-DPG, H+ ions or CO2 decrease O2 affinity, allowing more O2 delivery to tissues (Fig. 2.3). Some pathological variant haemoglobins are similar to Hb F in having a higher oxygen affinity than Hb A (Fig. 2.3); this leads, in adults, to a state of relative tissue hypoxia and the body compensates by increasing the number of red cells (secondary polycythaemia, see Chapter 26). In contrast, some pathological variant haemoglobins (e.g. Hb S, the major haemoglobin in sickle cell disease, see Chapter 17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree