The following section describes the clinical presentations of NTM infections and the relevant outbreak investigations.

Cardiothoracic Surgery

The first reported outbreak associated with cardiothoracic surgery occurred in 1976 in North Carolina.

35 During a 10-week period, sternal wound infections caused by

M chelonae were diagnosed in 24% (19/80) of patients who underwent cardiac surgery that included valve replacement with porcine and prosthetic valves as well as saphenous vein graft. Presenting symptoms were pain at the sternotomy incision site or drainage. The source of outbreak was never identified. The second outbreak occurred during a 2-week period in which

M fortuitum sternal wound infections developed in 44% (4/9) of patients who underwent cardiac surgery.

36 This second outbreak was caused by contaminated porcine valves and resulted in a nationwide outbreak affecting eight patients overall. Relative resistance to 2% formaldehyde, used to sterilize the valves, was implicated in this outbreak.

36,37In 1981, an outbreak of sternal wound infections and endocarditis occurred in Corpus Christi, Texas, and CDC investigators described the link between NTM-contaminated water and NTM infections.

38 This polymicrobial NTM outbreak was linked to two sources: first,

M fortuitum contaminated tap water in the operating room and, second,

M abscessus contaminated hospital ice water used to cool the cardioplegia solution. It was hypothesized that contamination of the operative field occurred when the bag of cardioplegia solution given to the anesthesiologist contaminated the anesthesiologist’s scissors.

38 These findings lead to discontinuing the use of tap water as a coolant in operating rooms.

Perhaps the most striking NTM outbreak associated with devices is the recent worldwide

M chimaera outbreak due to contaminated heater-cooler units (HCUs) used during cardiopulmonary bypass to warm and cool patients’ blood. Following a series of reports of

M chimaera infections in patients who underwent cardiothoracic procedures in the United States and Europe,

39,40,41 the CDC issued reports in October 2016 warning of the risk of NTM infections due to HCUs.

42 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) continues its ongoing investigation.

43 While many patients exposed to the implicated HCUs remained asymptomatic, clinical presentations included sternal wound infections, prosthetic valve endocarditis, bloodstream infections, and vascular graft infections.

40 Currently, more than 150 confirmed cases have been diagnosed worldwide.

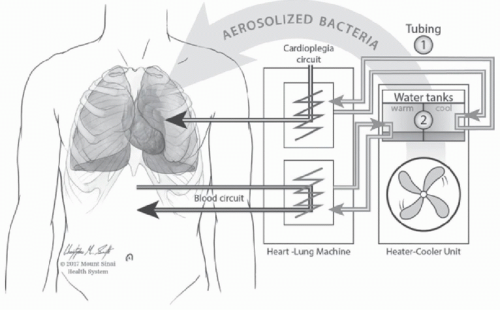

44In this outbreak, transmission occurred due to mycobacterial aerosolization from the HCUs into the operating room with subsequent contamination of the open surgical wound,

in situ replication, and subsequent dissemination.

24 The proposed route of transmission is displayed in

Figure 24-1. Because of the wide geographic distribution of cases, local contamination of the HCUs at individual hospitals seemed unlikely. Instead, the epidemiology implicated a point source outbreak. WGS of more than 100 isolates collected worldwide demonstrated that the isolates were highly related.

44 M chimaera was cultured from HCUs still in the manufacturing plant as well as water in the pump assembly area of the plant, supporting the claim that contamination occurred during production.

43 Several factors contributed to the delay in identifying this outbreak which included the sporadic attack rate, relatively long incubation period of

M chimaera, difficulty culturing NTM unless suspected, and the large geographic area involved.

The implications of this outbreak are enormous. Approximately 250 000 cardiothoracic surgical procedures requiring cardiopulmonary bypass are performed each year in the United States. Replacing all of the affected HCUs was not feasible without substantially impacting patient care.

24 M chimaera can be eradicated from external surfaces with routine disinfection of the outer surfaces of the HCU. However, the interior surfaces are inaccessible unless the units are dissembled which is not part of the usual maintenance

of HCUs and lead to these units serving as prolonged reservoirs for

M chimaera.44,45 The FDA and the manufacturer issued updated recommendations for disinfection and use of the involved HCUs.

43Notably, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) devices also run with circulating water. In 2015-2016, an outbreak with

M chimaera was linked with potable water faucet used to fill the devices.

46