Abstract

Neuroblastoma originates from primordial neural crest cells that normally give rise to adrenal medulla and sympathetic ganglia. While it accounts for 7% of all childhood malignancies, neuroblastoma accounts for 15% of childhood cancer mortality. Neuroblastoma is a disease of early childhood, though this tumor is occasionally seen in adolescents and young adults. Neuroblastoma usually presents with an adrenal mass or a tumor arising along the sympathetic neural chain. The most common presenting feature is an asymptomatic abdominal mass, with metastases detected at the time of diagnosis in 75% of cases. Biologic features of neuroblastoma tumors are of critical importance for risk assessment. Amplification of MYCN is strongly correlated with advanced-stage disease and treatment failure. Other key prognostic factors include age at diagnosis, disease stage, tumor histology, tumor cell ploidy, and the status of specific chromosomal segments. Modern treatment regimens are risk-based. Reduction in toxicity is a major goal in current trials for patients with non-high-risk neuroblastoma. Integration of multiple treatment modalities with targeted therapeutics is being studied in the setting of high-risk disease.

Keywords

Neuroblastoma, biology, prognosis, therapy

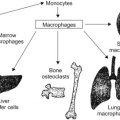

Neuroblastoma originates from primordial neural crest cells that normally give rise to adrenal medulla and the sympathetic ganglia.

Epidemiology

- •

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid tumor in children, accounting for 7% of all childhood malignancies. It accounts for 15% of childhood cancer mortality.

- •

Neuroblastoma is the most common malignancy in infants with an annual incidence of 10 per million live births.

- •

At diagnosis, 50% of patients are under 2 years of age, 75% under age 4, and 90% under age 10. Peak age of incidence is 2 years.

- •

In situ neuroblastoma is detected in one in 259 autopsies among infants less than 3 months of age. This 400-fold increase in the autopsy incidence of neuroblastoma compared with the clinical incidence of the tumor indicates that involution or maturation of the tumor occurs spontaneously in a moderate number of infants.

Predisposition

- •

Disorders involving the autonomic nervous system are occasionally seen in patients with neuroblastoma. Conditions associated with neuroblastoma are listed in Table 24.1 .

Table 24.1

Conditions Associated with Neuroblastoma

Neurofibromatosis type I

Hirschsprung disease with aganglionic colon

Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome

Pheochromocytoma

Heterochromia

Turner syndrome

Noonan syndrome

Cardiac malformations

- •

A family history of neuroblastoma is identified in 1–2% of cases and the tumors that arise in patients with familial disease are heterogeneous. The study of neuroblastoma predisposition has yielded remarkable insights into the biology of this disease.

- •

Mutations in PHOX2B (a key regulator of normal development of the autonomic nervous system) have been noted in a subset of patients with hereditary neuroblastoma.

- •

Heritable mutations in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene are an important cause of familial neuroblastoma.

Pathology and Biology

The diagnosis of neuroblastoma is based on the presence of characteristic histopathologic features of tumor tissue or the presence of tumor cells in a bone marrow aspirate or biopsy accompanied by elevated levels of urinary catecholamines. Neuroblastoma is one of the small round blue cell tumors of childhood and tumors are classified as histologically favorable or unfavorable according to the International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification (INPC) as shown in Table 24.2 .

| International neuroblastoma pathology classification | Original Shimada classification | Prognostic group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroblastoma | (Schwannian poor) a | Stroma-poor | |

| Favorable | Favorable | Favorable | |

| <1.5 years | Poorly differentiated or differentiating and low or intermediate MKI | ||

| 1.5–5 years | Differentiating and low MKI | ||

| Unfavorable | Unfavorable | Unfavorable | |

| <1.5 years | (a) Undifferentiated tumor b | ||

| (b) High MKI | |||

| 1.5–5 years | (a) Undifferentiated or poorly differentiated tumor | ||

| (b) Intermediate or high MKI tumor | |||

| ≥5 years | All tumors | ||

| Ganglioneuroblastoma, intermixed | (Schwannian stroma-rich) | Stroma-rich intermixed (favorable) | Favorable |

| Ganglioneuroma | (Schwannian stroma-dominant) | ||

| Maturing | Well differentiated (favorable) | Favorable c | |

| Mature | Ganglioneuroma | ||

| Ganglioneuroblastoma, nodular | (Composite Schwannian stroma-rich/stroma dominant and stroma poor) | Stroma-rich nodular (unfavorable) | Unfavorable c |

a Neuroblastoma subtypes detailed in Shimada et al. (1999) .

b Rare subtype, especially diagnosed in this age group. Further investigation and analysis required.

Clinical Features

Neuroblastoma usually presents with an adrenal mass or less commonly as a tumor arising anywhere along the sympathetic neural chain. The most common presenting feature is an asymptomatic abdominal mass, with distant metastases detected at the time of diagnosis in 75% of cases.

Anatomic Site

Clinical findings related to the anatomic site of the primary tumor are listed below:

- •

Head and neck

- •

Unilateral palpable neck mass

- •

Horner’s syndrome (myosis, ptosis, enophthalmos, anhydrosis)

- •

- •

Orbit and eyes

- •

Orbital metastases with periorbital hemorrhage (“raccoon eyes”)

- •

Exophthalmos, palpable supraorbital masses, ecchymosis, edema of eyelids and conjunctiva, ptosis

- •

Opsoclonus (“dancing eyes syndrome”)

- •

Heterochromia iridis, anisocoria

- •

- •

Chest

- •

Upper thoracic tumors: dyspnea, pulmonary infections, dysphagia, lymphatic compression, Horner syndrome

- •

Lower thoracic tumors: usually no symptoms

- •

- •

Abdomen

- •

Anorexia, vomiting

- •

Abdominal pain

- •

Palpable mass

- •

Massive involvement of the liver with metastatic disease; may result in respiratory insufficiency in the newborn

- •

- •

Pelvis

- •

Constipation

- •

Urinary retention

- •

Presacral mass palpable on rectal examination

- •

- •

Paraspinal area (dumbbell or hourglass-shaped neuroblastoma)

- •

Localized back pain and tenderness

- •

Limp

- •

Weakness of lower extremities

- •

Hypotonia, muscle atrophy, areflexia, hyperreflexia

- •

Paraplegia

- •

Scoliosis

- •

Bladder and anal sphincter dysfunction.

- •

- •

Lymph nodes: enlarged

- •

Bone: pain, limping and irritability in the young child associated with bone and bone marrow metastasis

- •

Lung: pulmonary parenchyma or pleura may rarely be involved. Lung involvement should be proven by biopsy or MIBG (I 131 -meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan) avidity due to its rarity in this disease

- •

Brain: metastatic involvement of the brain has been described, though it is more common in the setting of recurrent rather than newly diagnosed disease.

Other Symptoms

- •

Nonspecific constitutional symptoms include lethargy, anorexia, pallor, weight loss, abdominal pain, weakness, and irritability. These symptoms are more commonly seen in patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis.

- •

Intermittent attacks of sweating, flushing, pallor, headaches, palpitations, and hypertension related to catecholamine release can occur, but are relatively rare.

- •

Hypertension in children with neuroblastoma is usually due to renovascular compromise rather than catecholamine secretion.

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

- 1.

Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) secretion (Kerner–Morrison syndrome):

- a.

Signs and symptoms include intractable watery diarrhea resulting in failure to thrive, associated with abdominal distention and hypokalemia

- b.

Symptoms are due to the secretion of an enterohormone, VIP, by the neuroblastoma cells

- c.

VIP-secreting tumors typically have favorable histology

- a.

- 2.

Opsoclonus myoclonus ataxia syndrome (OMAS):

- a.

Signs and symptoms include bursts of rapid involuntary random eye movements in all directions of gaze (opsoclonus); and motor incoordination due to frequent, irregular, jerking of muscles of the limbs and trunk (myoclonic jerking)

- b.

Symptoms may or may not resolve after the tumor is removed

- c.

Prognosis for survival is favorable because OMAS is typically seen in patients with low-stage, biologically favorable tumors

- d.

There is a high incidence of chronic neurologic deficits, including cognitive and motor delays, language deficits, and behavioral abnormalities

- e.

All children presenting with this syndrome should be evaluated for the presence of neuroblastoma.

- a.

Diagnosis and Staging

When neuroblastoma is suspected, levels of the catecholamines homovanillic acid (HVA) and vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) should be analyzed to facilitate diagnosis. Tumor biopsies should be performed and should contain enough tissue to permit assessment of tumor histology and sufficient material for the molecular genetic analyses that are central to correct risk stratification and treatment planning. Open biopsies are preferred rather than needle biopsies. Criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis are described in Table 24.3 .

| Established if: |

| 1. Unequivocal pathologic diagnosis a is made from tumor tissue by light microscopy (with or without immunohistology, electron microscopy) |

| OR |

| 2. Bone marrow aspirate or trephine biopsy contains unequivocal tumor cells a (e.g., syncytia or immunocytologically positive clumps of cells) and increased urine or serum catecholamines or metabolites b |

a If histology is equivocal, karyotypic abnormalities in tumor cells characteristic of other tumors (e.g., t(11;22)) excludes a diagnosis of neuroblastoma, whereas genetic features characteristic of neuroblastoma (1p deletion, MYCN amplification) support this diagnosis.

b Includes dopamine, HVA, and/or VMA (levels must be >3.0 SD above the mean per milligram creatinine for age to be considered increased and at least two of these must be measured).

Once the diagnosis of neuroblastoma has been confirmed, a complete staging workup should be performed consisting of the following:

- •

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for evaluation of tumors in the abdomen, pelvis, or mediastinum. MRI decreases imaging-associated radiation exposure, especially when serial imaging evaluations are required.

- •

MRI is essential when evaluating paraspinal lesions as it permits evaluation of intraforaminal extension with the potential for cord compression.

- •

I 123 -MIBG scintigraphy is recommended for detection of bony metastases and occult soft tissue disease. MIBG is taken up by approximately 90% of neuroblastoma tumors.

- •

18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) may be useful to visualize primary and metastatic sites of disease, especially soft tissue disease, and should be utilized to diagnose and monitor response in patients whose tumors are not MIBG avid.

- •

Bone marrow disease should be assessed by performing bilateral bone marrow aspirates and biopsies. Standard histological analyses, including use of neuroblastoma immunohistochemical staining of biopsy specimens (e.g., CD56 or PGP9.5), should be performed.

- •

Table 24.4 shows the recommended tests for the assessment of extent of disease.

Table 24.4

Tests Recommended for Assessment of Extent of Disease

Tumor site

Recommended tests

Primary tumor

CT and/or MRI scan a with 3D measurements; MIBG scan b

METASTATIC SITES

Bone marrow

Bilateral posterior iliac crest marrow aspirates and trephine (core) bone marrow biopsies required to exclude marrow involvement. A single positive site documents marrow involvement. Core biopsies must contain at least 1 cm of marrow (excluding cartilage) to be considered adequate

Bone

MIBG scan; if tumor does not take up MIBG use 18 F-FDG-PET

Lymph nodes

Clinical examination (palpable nodes), confirmed histologically. CT and/or MRI scan for non-palpable nodes (3D measurements)

Abdomen/liver

CT and/or MRI scan a with 3D measurements

Chest

CT/MRI necessary if abdominal mass/nodes extend into chest, or evidence of soft tissue MIBG uptake. Consider inclusion if patient has non-thoracic primary with disseminated disease to allow evaluation for distant nodal metastases

AP, anteroposterior.

From: Brodeur et al. (1993) and Sharp et al. (2009) .

a Ultrasound considered suboptimal for accurate 3D measurements in complex locoregional tumors; may be considered for serial monitoring if expertise in US imaging exists and tumors are well circumscribed (INRGSS L1).

b The MIBG scan is applicable to all sites of disease. I-123 MIBG is the recommended tracer.

Staging Systems

Table 24.5 shows the International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS) and the more recently developed International Neuroblastoma Risk Group Staging System (INRGSS).

- •

The INSS uses extent of surgical resection, presence of lymph node involvement, and metastatic disease to determine disease stage

- •

The INRGSS uses presurgical assessments of extent of disease based upon results of imaging studies and bone marrow morphology. Radiologic features are used to distinguish locoregional tumors that do not involve local structures (INRGSS L1) from locally invasive tumors (INRGSS L2, exhibiting image-defined risk factors (IDRF)). Table 24.6 shows neuroblastoma IDRF. Stages M and MS refer to tumors that are metastatic, however the MS designation refers to patients under 18 months of age who have metastases restricted to skin, liver, and/or bone marrow.

Table 24.6

Neuroblastoma Image-Defined Risk Factors (IDRF) By Location

NECK:

Tumor encasing carotid and/or vertebral artery and/or internal jugular vein

Tumor extending to base of skull

CERVICO-THORACIC JUNCTION:

Tumor encasing brachial plexus roots

Tumor encasing subclavian vessels and/or vertebral and/or carotid artery

Tumor compressing the trachea

THORAX:

Tumor encasing the aorta and/or major branches

Tumor compressing the trachea and/or principal bronchi

Lower mediastinal tumor, infiltrating the costovertebral junction between T9 and T12

Significant pleural effusion with or without presence of malignant cells

THORACO-ABDOMINAL:

Tumor encasing the aorta and/or vena cava

ABDOMEN/PELVIS:

Tumor infiltrating the porta hepatis

Tumor infiltrating the branches of the superior mesenteric artery at the mesenteric root

Tumor encasing the origin of the celiac axis and/or of the superior mesenteric artery

Tumor invading one or both renal pedicles

Tumor encasing the aorta and/or vena cava

Tumor encasing the iliac vessels

Pelvic tumor crossing the sciatic notch

Ascites with or without presence of malignant cells

DUMBBELL TUMORS WITH SYMPTOMS OF SPINAL CORD COMPRESSION:

Any localization

INVOLVEMENT/INFILTRATION OF ADJACENT ORGANS/STRUCTURES:

Pericardium, diaphragm, kidney, liver, duodeno-pancreatic block, mesentery, and others

From: Monclair et al. (2009) , with permission.

| INSS | INRGSS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 . | Localized tumor with complete gross excision, with or without microscopic residual disease; representative ipsilateral lymph nodes negative for tumor microscopically (nodes attached to and removed with the primary tumor may be positive) | Stage L1 . | Localized tumor not involving vital structures (as defined by the list of image-defined risk factors, Table 24.6 ) and confined to one body compartment |

| Stage 2A . | Localized tumor with incomplete gross excision; representative ipsilateral non-adherent lymph nodes negative for tumor microscopically | Stage L2 . | Locoregional tumor with presence of one or more image-defined risk factors |

| Stage 2B . | Localized tumor with or without complete gross excision, with ipsilateral non-adherent lymph nodes positive for tumor. Enlarged contralateral lymph nodes must be negative microscopically | ||

| Stage 3 . | Unresectable unilateral tumor infiltrating across the midline, a with or without regional lymph node involvement; or localized unilateral tumor with contralateral regional lymph node involvement; or midline tumor with bilateral extension by infiltration (unresectable) or by lymph node involvement | ||

| Stage 4 . | Any primary tumor with dissemination to distant lymph nodes, bone, bone marrow, liver, skin, and/or other organs (except as defined for stage 4S) | Stage M . | Distant metastatic disease (except stage MS) |

| Stage 4S . | Localized primary tumor (as defined for stage 1, 2A, or 2B), with dissemination limited to skin, liver, and/or bone marrow b (limited to infants <1 year of age) | Stage MS . | Metastatic disease in children younger than 18 months with metastases confined to skin, liver, and/or bone marrow |

a The midline is defined as the vertebral column. Tumors originating on one side and crossing the midline must infiltrate to or beyond the opposite side of the vertebral column. A grossly resectable tumor arising in the midline from pelvic ganglia or the organ of Zuckerkandl would be considered stage 1. A midline tumor that extended beyond one side of the vertebral column and was unresectable would be considered stage 2A. Ipsilateral lymph node involvement would make it stage 2B, whereas bilateral lymph node involvement would make it stage 3. A midline primary tumor with bilateral infiltration that was not resectable would be considered stage 3. A tumor of any size with malignant ascites or peritoneal implants would be stage 3 (but a thoracic tumor with malignant pleural effusion unilaterally would be stage 2B).

b Marrow involvement in stage 4S should be minimal, that is, <10% of total nucleated cells identified as malignant on bone marrow biopsy or on marrow aspirate. More extensive marrow involvement would be considered to be stage 4. The MIBG scan should be negative in the marrow.

Treatment

Treatment modalities used are surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy. The role of each is determined by clinical and molecular characteristics determined at diagnosis such as age, stage, and biological features.

Surgery

The role of surgery is to establish the diagnosis, provide tissue for biologic studies, stage the disease, and excise the tumor (when feasible).

- •

Timing of surgical resection is dependent upon radiographic features of response to treatment and upon a patient’s risk stratification.

- •

Residual tumor does not adversely affect prognosis in low- or intermediate-risk disease, while an attempt at complete surgical resection is recommended for patients with high-risk disease if resection can be performed without significant morbidity.

- •

Attempted surgical resection of localized tumors (INSS stage 1 or stage 2, INRGSS L1) is the mainstay of therapy. Recent studies, however, demonstrated that infants less than 6 months of age with small localized tumors (INSS stage 1, INRGSS L1) of the adrenal gland are likely to have spontaneous tumor regression. An alternative treatment option in this cohort of patients is to perform surgery only in those cases in which an increase by greater than 25% from baseline in tumor size is demonstrated by serial imaging studies.

- •

Surgical resection that may result in loss or damage to vital organs should be avoided, especially in the setting of low- and intermediate-risk neuroblastoma. In such cases, chemotherapy should be administered prior to attempted surgical resection.

- •

Delayed surgical resection of primary disease should be performed in patients with evidence of metastatic disease.

Radiation Therapy

Although neuroblastoma is an extremely radiosensitive tumor, the long-term risks of radiotherapy are generally not warranted in patients with low- and intermediate-risk disease. Radiotherapy is, however, an important component of therapy for patients with high-risk disease.

Radiotherapy may be warranted in the following clinical scenarios involving patients with low- or intermediate-risk neuroblastoma:

- •

Neonates with INSS stage 4S neuroblastoma who develop respiratory distress secondary to hepatomegaly or hepatic failure and for whom treatment with chemotherapy is not feasible or has been ineffective.

- •

Children with neuroblastoma-associated spinal cord compression and neurologic compromise for whom there is a contraindication to the use of emergent chemotherapy. Laminectomy has also been used to rapidly reduce cord compression. Both radiation and surgery are associated with a significant incidence of vertebral body damage and scoliosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree