48 Neuro-Oncology in the Developing World

A 35-year-old man with a 10-month history of headaches and blurry vision presented to the neurosurgeon at the University Teaching Hospital. He had sought help for his symptoms from a traditional medicine man. As his symptoms progressed, he had been reluctant to present at the referral center because of the distance from his village and the expected long wait to see the specialist. He has lost vision in the right eye and barely counts fingers on the left. The left fundus showed papilledema. At consultation the neurosurgeon requested a computed tomography (CT) scan, and this meant the patient had to travel back to his village to raise the funds for it. He returned after 4 weeks and had the CT scan done, which revealed a large right frontal meningioma. By this time he had become blind in both eyes. He was operated on 4 weeks later with subtotal excision of the tumor due to significant intra-operative blood loss. Due to processing delays and the fact that only one of the institution’s pathologists was conversant with neuropathology, the histology of the excised tumor was reported as grade III 2 months postoperatively. The radiotherapy facility was 700 km away and there was no guarantee of its staff attending to the patient immediately due to the backlog of patients and frequent machine malfunction. This man’s tumor progressed and he deteriorated clinically.

This case scenario is an example of what is often encountered in developing countries around the world. This chapter discusses the challenges in neuro-oncology in developing countries and suggests solutions.

There are various indices that have been used in the definition of a developing country. The World Bank based its classification on gross national income per capita (GNI). This stratifies countries into low-, middle- (upper and lower), and high-income countries. The term developing is then applied to the low- and middle-income countries. This results in a heterogeneous mix of countries, at different developmental stages with varying indices. The World Bank states, “The use of the term ‘developing’ is convenient; it is not intended to imply that all economies in the group are experiencing similar development or that other economies have reached a preferred or final stage of development.” Classification by income does not necessarily reflect development status. Based on this category, all of Africa and the Middle East except Israel, most countries in the Caribbean and South America, and a part of Europe are classified as developing countries.1

Neuro-Oncology as a Subspecialty

Neuro-Oncology as a Subspecialty

The evolution of neurosurgery as a specialty over the last century has birthed many subspecialties including neuro-oncology, which has over the years become well established in most neurosurgical centers in the technologically advanced world. Neuro-oncology has gone further to become a distinct entity even within neurosurgical associations such as the Tumor Section of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons.2 The Society of Neuro-Oncology was also formed to be a torchbearer for the subspecialty both in basic and clinical research. Neuro- oncology has not only become progressively technologically driven, but there is continued emphasis, as in most other neurosurgical subspecialties, on a multidisciplinary approach.3 Thus, it is heavily dependent on the availability of both structural and personnel resources. The persistent pursuit of excellence in neuro-oncology practice has become part of the needed impetus for the development of new and expensive technologies directed at improving patient safety and the quality and quantity of survival.

The availability of the enormous resources at the disposal of the neuro-oncologist in the developed world is taken for granted and is viewed as a needed sine qua non for safe practice. Although patients all over the world would be appreciative of these revolutionary efforts in neuro-oncology, the state of the practice of this subspecialty in the less privileged settings is lagging behind. Central nervous system (CNS) tumors, as with every other disease, know no boundaries, and even though the precise incidence and prevalence are not as well documented in the developing world, their abundant presence in the developed world is clearly evident.4–9

Epidemiology of Brain Tumors in the Developing World

Epidemiology of Brain Tumors in the Developing World

Although the main efforts in neurosurgery in the developing world have centered on trauma and pediatric neurosurgical care, satisfying an undeniable need for these lifesaving treatments, increasing evidence demonstrates that tumors of the CNS comprise a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the developing world.10 Similar epidemiology for pediatric CNS tumors in Morocco as in previously published data for developed countries has been demonstrated,11,12 although others have reported a significantly different distribution of malignancies of childhood cancer compared with that in the developed nations.13 The distribution of CNS tumor types among all age groups in a retrospective study of pathology specimens in Egypt demonstrated overall similar breakdown of tumor types and demographics.14 A report of skull base operations in Nigeria seems to parallel the epidemiology of adult skull base pathology in developed nations.15

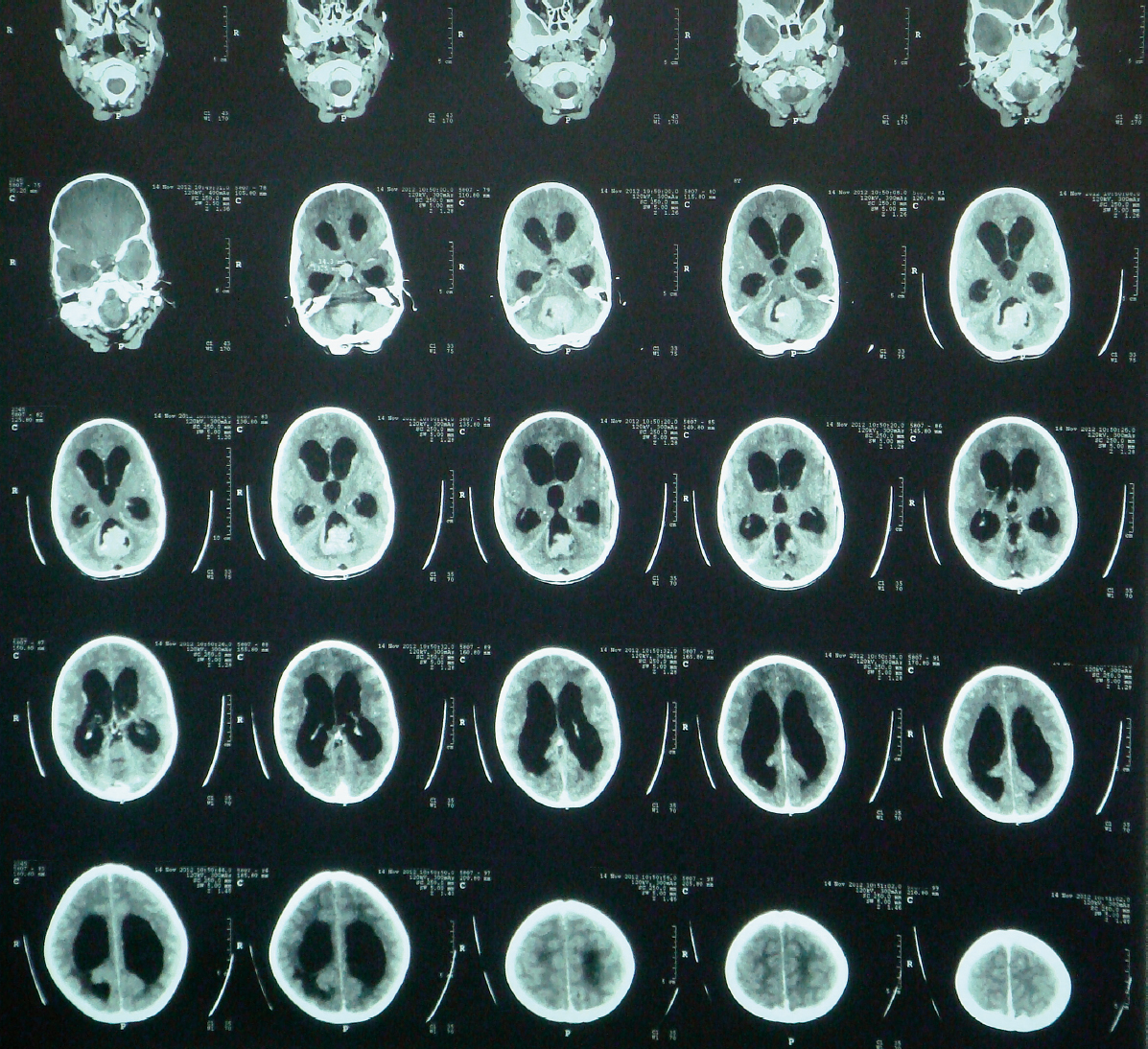

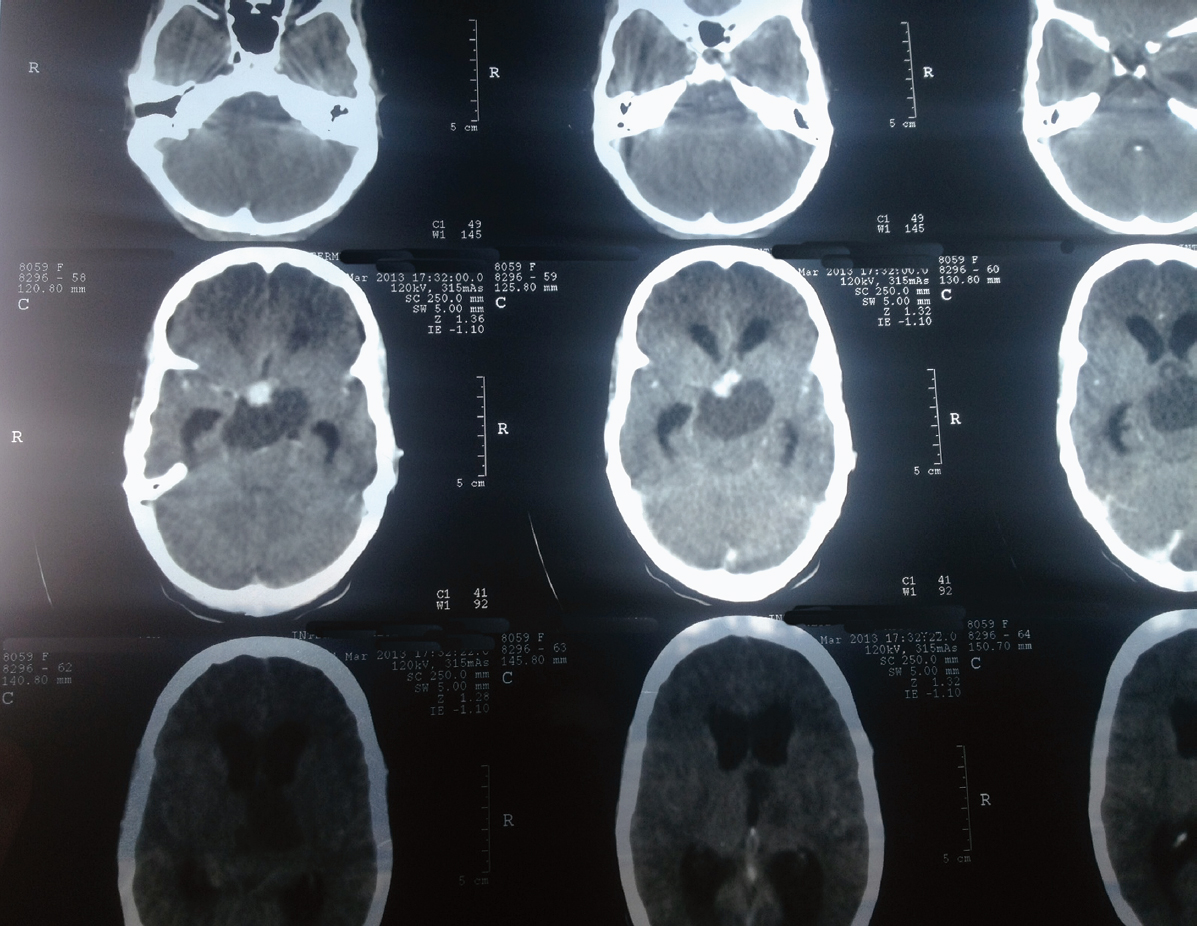

However, some key epidemiological differences do exist such as a preponderance of Burkitt lymphoma metastatic brain lesions reflecting the increased risk of Burkitt’s lymphoma in Africa.16 Because of delayed diagnosis, patients in developing countries often present with advanced disease, with up to 60% of patients having a Karnofsky Performance Scale score of less than 70, due to a variety of factors (Figs. 48.1 and 48.2).15,17 In addition, some preliminary studies of tumor biology have suggested some geographical differences.18

The Surgical Neuro-Oncologist

The Surgical Neuro-Oncologist

The adequately trained surgical neuro-oncologist is the key to the surgical treatment of tumors of the CNS. The paucity of neurosurgeons in the developing world is well documented, with various efforts being implemented to increase their numbers (Table 48.1).4,19–23 The ratio of neurosurgeons to the population may be as low as 1 to 10.5 million in Tanzania23 and as high as 1 to 85,449 in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.19 In Asia one neurosurgeon serves from 600,000 to 3.5 million people.4

Access to the few neurosurgeons is further hindered by their location within big teaching hospitals, in the urban centers.19 The limited number of available providers and the restricted access to care with increasing patient load results in delayed presentation and resultant enormous morbidity and mortality seen in patients with CNS tumors in these countries.4,19–23 These factors have strengthened the call for the training of more general neurosurgeons and even the training of general surgeons to manage neurosurgical conditions. It is important to note that although these calls seek to find solutions to the inadequate manpower, it has also deemphasized subspecialty training. Neuro-oncology practice has over the years become established through the training of surgical neuro-oncologists, and the impact of this has been underscored.20 Therefore, this may necessitate a paradigm shift in developing countries whereby instead of focusing exclusively on basic neurosurgical needs such as trauma and hydrocephalus, one gradually entrenches surgical neuro-oncology as an established subspecialty.

Special Consideration

• Focus on the care of trauma and congenital abnormalities should not stunt the growth of neuro-oncology as a distinct subspecialty in developing countries.

Neuro-Oncology in the Preoperative Period

Neuro-Oncology in the Preoperative Period

The effective preoperative care of the neuro-oncology patient involves timely recognition, referral, clinical evaluation, and imaging. Delay of care often occurs at each of these stages. Referral depends foremost on detection of neurologic abnormality, which is often not brought to the attention of medical personnel until at an advanced clinical stage, because of the lack of access to medical care, the lack of funds, or the initial use of traditional healing.24 Religious, cultural, and financial factors have also been identified as all playing a role in delayed diagnosis of CNS tumors in adults in Africa.17 The importance of educating both general practitioners and the public regarding sentinel symptoms of malignancy have included resources such as a public television campaign and translated material from international cancer organizations in their future educational projects.25

Imaging modalities include anatomic, physiological, and functional techniques. The availability of imaging facilities aids not just in the delineation of tumors, but also in the establishment of their spatial relationship with normal structures to help improve the accuracy of diagnosis and optimize surgical planning. Most developing countries are lacking the most basic of these facilities or have, at most, CT capability.5,21 A report published as recently as 2001 indicates that X-ray is a common imaging modality for the diagnosis of brain tumors.26 Available magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines are of low tesla strength, requiring longer imaging durations and therefore the scans are more susceptible to motion artifact.27 In spite of this, the utility of low-field MRI in evaluating sellar lesions has been demonstrated, where pertinent anatomic relations are visible such as encasement or narrowing of the carotid in sellar meningiomas and the presence of microadenomas.27 Aside from access to imaging studies, the impact of unrelated disease burden may make interpretation of imaging studies more complex than in developed countries. Difficulties have been recorded in interpreting positron emission tomography (PET) scans in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) because of direct effects of both the disease and its treatment in South Africa.28

Pitfall

• Other comorbidities may affect the interpretation of imaging studies.

It is undeniable that the factors contributing to preoperative detection and workup of CNS tumors are varied and include the immense challenges of lack of funding and infrastructure.19,21,22,29,30 The absence of strong, coordinated, and persistent advocacy by the existing neurosurgeons in these regions may also continue to impede development in the area of neuro-oncology.19

Pitfall

• The excision of CNS tumors using the most basic neuro-surgical instruments is generally not as safe as surgery with advanced technology.

In the Operating Room

In the Operating Room

The essence of the operating room is captured in these words: “The operating room is a work of art with a choreography and emotion of its own…. The patient has trusted the neurosurgeon with his life, his person, his speech, and his memory.”31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree