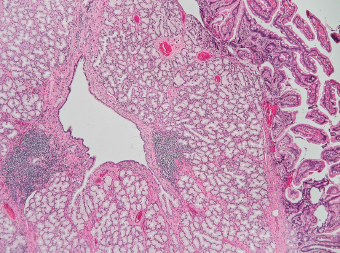

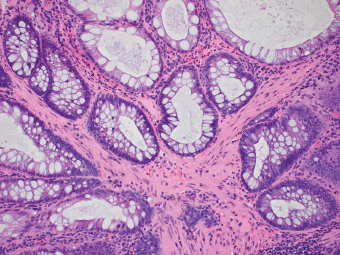

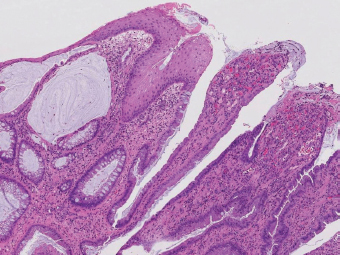

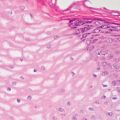

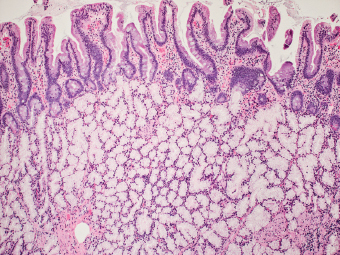

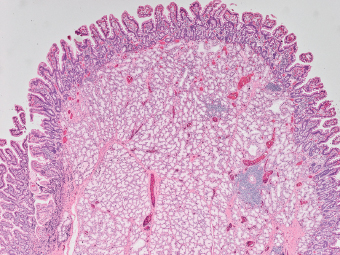

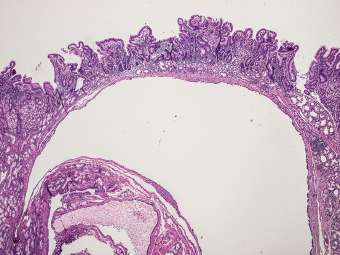

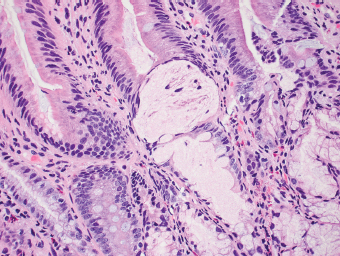

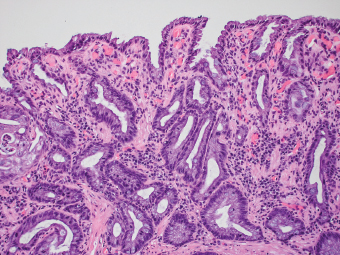

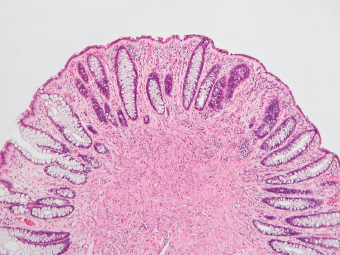

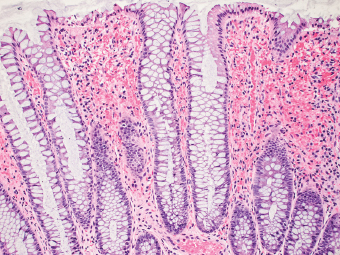

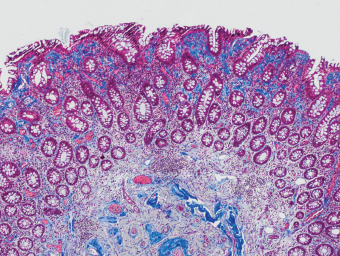

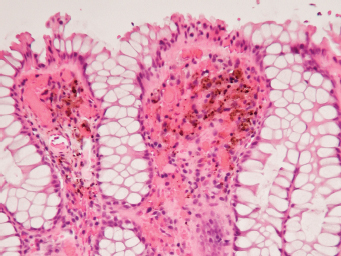

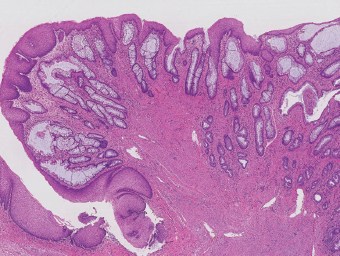

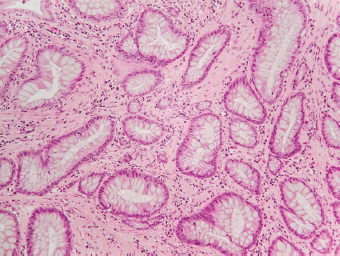

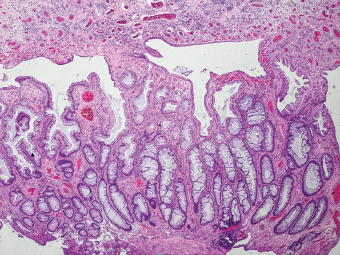

5 Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome Polyp Inflammatory Myoglandular Polyps Neoplastic mimics of the intestines can arise from any layer of the intestines, but the majority of them arise from the mucosa and submucosa. Both small and large intestines are constituted by mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and adipose tissue. These constituents of the intestines are fairly similar throughout; consequently, similar neoplastic mimics occur in both small and large intestines (Table 5.1). Neoplastic mimics of the intestines assume polypoid configuration, causing signs and symptoms indistinguishable from intestinal neoplasms, such as obstruction, intussusception, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Some, such as hyperplastic polyps, are commonly encountered during endoscopic examination, while others, such as inflammatory fibroid polyp, are less common than true neoplasm of the intestines. Polypoid neoplastic mimics of the intestines are the most common lesions encountered during endoscopic examination. They are asymptomatic when small, but when large, they can cause gastrointestinal bleeding, obstruction, or intussusception. Large polypoid neoplastic mimics can be detected by radiologic studies. The gross morphology of many of the polypoid neoplastic mimics are similar to one another. In addition, mechanical trauma, mucosal prolapse, ulceration, and subsequent regeneration impart common histopathologic features, that is, inflammatory granulation tissue formation with or without fibrinopurulent cap, atypical degenerated inflammatory cells, atypical stromal and endothelial cell proliferation, atypical surface epithelial regeneration, dark basophilic regenerative crypts, various degrees of muscularis mucosa and vascular thickening, and lamina propria fibrosis. Polypoid neoplastic mimics of the intestines include hyperplastic polyps, lesions associated with mucosal prolapse, hamartomatous polyps, inflammatory-type polyps, and heterotopic tissue. Segmental stricture or obstruction is a less common presentation of neoplastic mimics. It is often the result of chronic transmural inflammatory processes, such as Crohn’s disease, sigmoid diverticulitis, radiation enteritis, and paraduodenal pancreatitis. Crohn’s disease can occur in any segment of the small and large intestines, diverticulitis is commonly in the sigmoid, chronic radiation enteritis is in the duodenum of patients with pancreatobiliary cancer or in the ileum of patients with pelvic or rectal malignancy. TABLE 5.1 Neoplastic Mimics of the Intestines GROSS CONFIGURATION NEOPLASTIC MIMICS NEOPLASM Mucosal plaques or submucosal nodule Gastric heterotopia Adenomatous polyp Adenomyoma Adenocarcinoma, primary or metastatic Brunners gland hamartoma Adenomatous polyp Colitis/enteritis cystica profunda Adenocarcinoma Xanthoma/xanthelasma Signet ring cell, adenocarcinoma, adenomatous polyp Pneumatosis intestinalis Adenocarcinoma Malakoplakia Adenocarcinoma, sarcoma Mucosal granularity Brunners gland hyperplasia Adenomatous polyp Mucosal prolapse/solitary rectal ulcer Adenocarcinoma Polyps Mucosal prolapse polyp Adenomatous polyp Inflammatory cloacogenic polyp Adenomatous polyp, adenocarcinoma Hamartomatous polyp Adenomatous polyp Juvenile polyp Adenomatous polyp Ganglioneuroma Adenomatous polyp Mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma Adenomatous polyp Diverticular disease associated polyp Adenomatous polyp Inflammatory fibroid polyp Adenomatous polyp, stromal tumor Lipomatous hypertrophy of ileocecal valve Lipoma, adenomatous polyp, stromal tumor Inflammatory polyp Adenomatous polyp Lymphangiectasia Adenomatous polyp Hypertrophic anal papilla Adenomatous polyp, squamous cell carcinoma Stricture and/or ulceration Diverticular disease Adenocarcinoma Crohn’s disease Adenocarcinoma, lymhoma Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome Adenocarcinoma Paraduodenal pancreatitis Adenocarcinoma Brunner gland hyperplasia is a hyperplastic proliferation of mucin-secreting glands that is located predominantly in the duodenal submucosa, creating small sessile polypoid excrescences or a nodular appearance of the duodenal bulb mucosa. Although Brunner glands are predominantly located in the submucosa, they often focally transgress through the muscularis mucosa into the lamina propria, particularly in hyperplastic/inflammatory condition (Figure 5.1). A large pedunculated polyp composed of Brunner glands is often referred to as Brunner gland hamartoma, which often represents a large mucosal prolapse lesion of preexisting Brunner gland hyperplasia (Figure 5.2). The use of the term Brunner gland adenoma is discouraged because of the lack of evidence of malignancy and the potential confusion with adenomatous polyp of the duodenum. Patients may present with obstructive symptoms, intussusception, or gastrointestinal hemorrhage (297–299), but Brunner gland hyperplasia and hamartoma are usually incidental findings. Brunner gland hyperplasia and hamartoma are composed of mucin-secreting glands with basally located nuclei, similar to those of pyloric glands, arranged in lobules that are separated by thin fibromuscular bands (Figure 5.3). Interlobular ducts are distributed normally and lined by cuboidal to short columnar epithelium. Obstruction of these ducts may lead to submucosal cystic dilatation of Brunner glands (300) (Figure 5.4). The endoscopic differential diagnoses of Brunner gland hyperplasia and hamartoma are predominantly neoplastic diseases, including adenomatous polyp of the duodenum, carcinoid tumor, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Microscopically, these neoplastic lesions are distinctively different from the lesions of Brunner gland. Other neoplastic mimics such as pancreatic heterotopia and minor papilla of the accessory pancreatic duct are commonly found in proximal duodenum, in similar location to Brunner gland lesions. Superficial mucosal biopsy or excision of pancreatic heterotopia often captures benign ducts similar to the interlobular ducts of Brunner gland only, without pancreatic parenchyma in pancreatic heterotopia and minor papilla. However, in addition to ducts, Brunner gland lesions always consist of packed mucin-producing glands in lobules. FIGURE 5.1 Brunner gland hyperplasia with transgression to the lamina propria. FIGURE 5.2 Polypoid Brunner gland hamartoma. FIGURE 5.3 Brunner gland hamartoma composed of mucin glands that are arranged in lobules with centrally located interlobular duct. FIGURE 5.4 Dilatation of Brunner gland produces submucosal cyst. Crushed artifact of the Brunner gland lesions may render spindle cell appearance mimicking spindle cell lesion, or may render dissociated mucin-containing cells with peripherally located nuclei mimicking signet ring cell carcinoma (Figure 5.5). FIGURE 5.5 Crushed artifact of Brunner gland imparts mucin pool with floating exfoliated cells. Localized or segmental mucosal prolapse of the intestines results in various polypoid and ulcerating lesions, particularly in the large intestine, ranging from mucosal prolapse polyp or polypoid prolapsing mucosal folds, diverticular-disease associated polyp, inflammatory cloacogenic polyp, enteritis and colitis cystica profunda/polyposa, and solitary rectal ulcer. The term “mucosal prolapse syndrome” has been suggested as a unifying term for disorders in which mucosal prolapse, either overt or occult, is the underlying pathogenetic mechanism (301). The mucosa and crypts of the large intestine are tethered to the muscularis mucosa by thin strands of smooth muscle. When mucosal prolapse occurs for a prolonged period of time, these strands of smooth muscle become hyperplastic; therefore, many of the mucosal prolapse lesions share common histopathologic features, that is, smooth muscle hyperplasia of the lamina propria, thickening of muscularis mucosa, crypt architectural distortion with angulation and elongation of the crypts, and hyperplasia of crypt epithelium (Figure 5.6). FIGURE 5.6 Common features of mucosal prolapse include hyperplastic, distorted, and angulated crypts separated by smooth muscle bundles. Mucosal prolapse polyp is a benign neoplastic mimic seen in the large intestine, particularly in the sigmoid and rectum. Mucosal prolapse polyps tend to be small sessile polyps measuring less than 2 cm. When associated with diverticular disease, they are referred to as diverticular disease-associated polyps; they often are pedunculated, large, can be multiple, and may mimic neoplastic process (302). Inverted diverticulum may show similar endoscopic and histologic appearance (303). Mucosal prolapse polyps display strands of thickened muscularis mucosa that extend around the base of crypts and into the overlying lamina propria, encircling and compressing the crypts (Figures 5.7 and 5.8). The crypts are distorted and angulated. The surface epithelium is often eroded or shows regenerative hyperplasia with surface erosion. In larger polyps, repeated trauma by peristalsis cause torsion of blood vessels, resulting in ischemia and lamina propria fibrosis. In addition to the general features of mucosal prolapse, diverticular disease-associated polyps often show congestion, thickening of subepithelial basement membrane, and evidence of old hemorrhage represented by hemosiderin deposition in the lamina propria (Figures 5.9–5.11). FIGURE 5.7 Mucosal prolapse polyp with hypertrophy of muscularis mucosa extending to the overlying lamina propria. FIGURE 5.8 Hyperplastic smooth muscle emanating from muscularis mucosa surrounding and compressing overlying crypts. FIGURE 5.9 Congestion and hemorrhage in diverticular disease-associated mucosal prolapse polyp. FIGURE 5.10 Trichrome stain shows thickening of subepithelial basement membrane in mucosal prolapse syndrome. FIGURE 5.11 Brown pigment in the lamina propria of diverticular disease-associated mucosal prolapse polyp indicating old hemorrhage. Inflammatory cloacogenic polyp is a benign polypoid mucosal prolapse lesion at or very near the anorectal junction (304). It is a localized expression of the mucosal prolapse syndrome; therefore, it is often associated with solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. It frequently mimics anorectal malignancy such as adenomatous polyp or rectal adenocarcinoma (305–307). Inflammatory cloacogenic polyp occurs in both children and adults (308). It bleeds easily and can cause tenesmus. Histologically, inflammatory cloacogenic polyp shows angulated regenerative crypts between bundles of hyperplastic smooth muscle in the lamina propria and thickened muscularis mucosa (Figures 5.12 and 5.13). The surface epithelium consists of an admixture of rectal columnar mucosa, anal squamous epithelium, and transitional epithelium (Figure 5.14). The superficial crypt epithelium is hyperplastic and can be serrated. Erosion is often accompanied by fibrinopurulent cap. In addition, the base of the colonic crypts in inflammatory cloacogenic polyp may be cystically dilated, and cysts may be observed in the submucosa as well, similar to colitis cystica profunda. A variant of inflammatory cloacogenic polyp with inflammatory granulation tissue and fibrin cap that occurs more proximally in the sigmoid or rectum is often referred to as inflammatory “cap” polyp (Figure 5.15). FIGURE 5.12 Inflammatory cloacogenic polyp showing remarkable smooth muscle hyperplasia in the lamina propria and thickening of the underlying muscularis mucosa. The surface of the polyp is eroded. The colonic crypts at the base of polyp are cystically dilated. FIGURE 5.13 Angulated colonic crypts surrounded by smooth muscle bundles in inflammatory cloacogenic polyp. FIGURE 5.14 Transitional squamous and colorectal epithelium at the surface of inflammatory cloacogenic polyp. FIGURE 5.15 Inflammatory “cap” polyp. The differential diagnoses of inflammatory cloacogenic polyp include adenomatous polyp, rectal adenocarcinoma, hemorrhoids, hypertrophic anal papillae, and anal condyloma. Because of the markedly distorted and angulated crypts, inflammatory cloacogenic polyp may mimic rectal adenocarcinoma, especially when the specimen is suboptimal with cautery or fixation artifact. The stroma in low-lying rectal adenocarcinoma is desmoplastic stroma rather than an admixture of true lamina propria and hyperplastic smooth muscle bundles as in inflammatory cloacogenic polyp. In addition, the crypt epithelium in inflammatory cloacogenic polyp does not exhibit nuclear pleomorphism, loss of polarity, or atypical mitoses. Hemorrhoids, hypertrophic anal papillae, and anal condyloma are histologically distinct from inflammatory cloacogenic polyp. Inflammatory cloacogenic polyp can also occur in patients with inflammatory bowel disease; therefore, in this condition, the distinction should be made from inflammatory polyp, which can also have prolapse changes if located close to the anal verge. In children, inflammatory cloacogenic polyp should be distinguished from juvenile polyp. Juvenile polyp tends to exhibit more myxoinflammatory lamina propria with cystic dilatation of the crypts rather than angulated and distorted crypts due to compression by smooth muscle bundles in inflammatory cloacogenic polyp.

Neoplastic Mimics of the Intestines

BRUNNER GLAND HYPERPLASIA AND HAMARTOMA

BRUNNER GLAND HYPERPLASIA AND HAMARTOMA

INFLAMMATORY CLOACOGENIC POLYP

INFLAMMATORY CLOACOGENIC POLYP

ENTERITIS AND COLITIS CYSTICA PROFUNDA/POLYPOSA

ENTERITIS AND COLITIS CYSTICA PROFUNDA/POLYPOSA

SOLITARY RECTAL ULCER SYNDROME

SOLITARY RECTAL ULCER SYNDROME

NEOPLASTIC MIMICS ASSOCIATED WITH DIVERTICULAR DISEASE

NEOPLASTIC MIMICS ASSOCIATED WITH DIVERTICULAR DISEASE

INTRODUCTION

BRUNNER GLAND HYPERPLASIA AND HAMARTOMA

MUCOSAL PROLAPSE LESIONS

MUCOSAL PROLAPSE POLYP

INFLAMMATORY CLOACOGENIC POLYP

ENTERITIS AND COLITIS CYSTICA PROFUNDA/POLYPOSA

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree