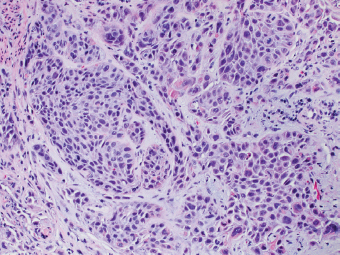

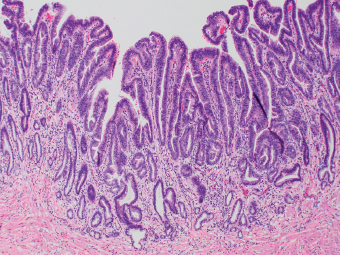

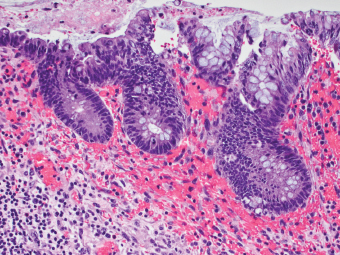

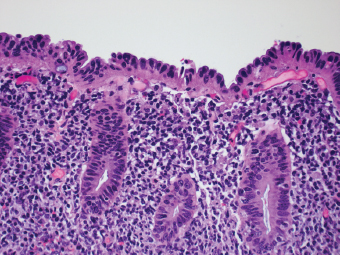

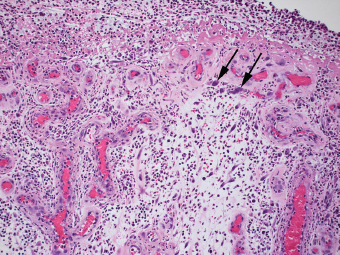

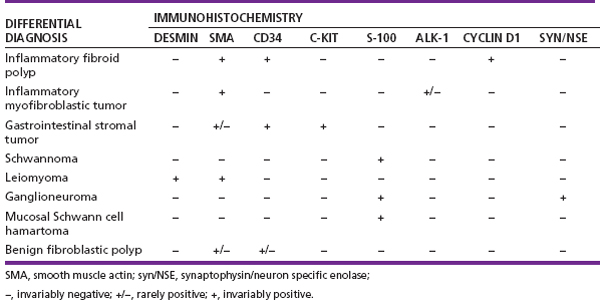

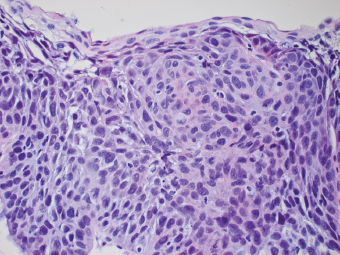

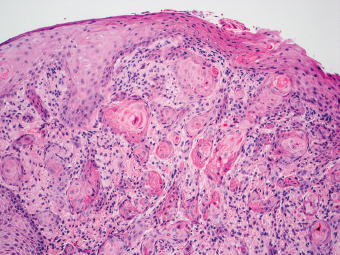

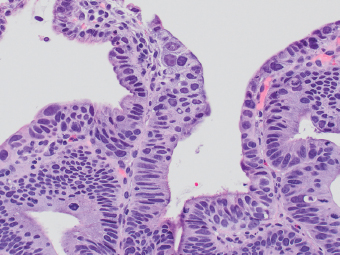

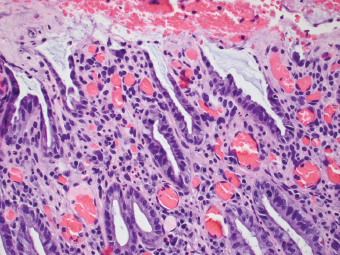

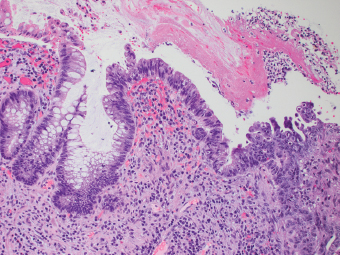

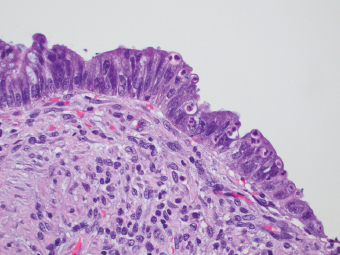

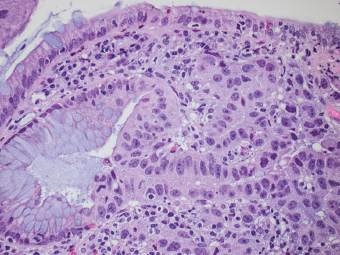

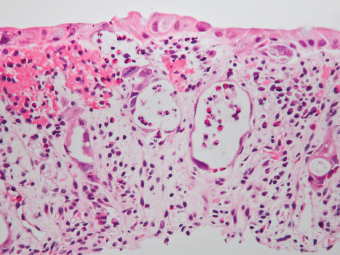

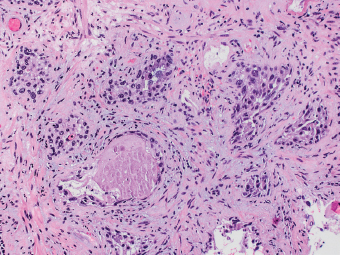

2 Lipomatous Hypertrophy of the Ileocecal Valve There are many different types of neoplastic mimics that occur in the gastrointestinal tract, but many are even less common than neoplasm of the gastrointestinal tract. Knowledge of their existence is of clinical importance to avoid misinterpretation that could significantly alter patient care and management. Lesions discussed in this chapter are considered neoplastic mimics based on their gross endoscopic or histomorphology. The gross appearances of neoplastic mimics vary widely. Many of neoplastic mimics take the form of exophytic lesions or plaques, whereas others cause segmental stricture or luminal narrowing. Many of the exophytic neoplastic mimics cause gastrointestinal bleeding because of peristaltic action of the gastrointestinal tract, which results in mucosal prolapse, erosion, and ulceration. Different types of epithelium cover the mucosal surface of the gastrointestinal tract, but the components of the deeper layer are fundamentally similar throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Consequently, many neoplastic mimics, particularly those arising from stromal component or muscular layer, are morphologically similar and can be found throughout the gastrointestinal tract, while those arising from the mucosa demonstrate a more restricted anatomic distribution. Epithelial regeneration occurs as normal physiologic turnover of squamous and glandular mucosa throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Epithelial regeneration is accelerated in response to mucosal injury, inflammation, erosion, or ulceration, in which regenerative epithelium is often atypical and may mimic dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or cancerization of the benign epithelium by metastatic carcinoma. In the esophagus, as an esophageal ulcer heals, squamous epithelium grows along the surface of the granulation tissue at the base of the ulcer. The basal layer appears basophilic with elongation of papillae that extend to roughly equal depths and widths within the granulation tissue. This basophilic regenerative epithelium is frequently thickened and referred as “pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,” which can mimic squamous cell carcinoma in situ or even invasive carcinoma when tissue sections are maloriented (Figure 2.1). The distinction between pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from squamous cell carcinoma is the presence of myxoinflammatory stroma surrounding islands of squamous epithelium in pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia rather than desmoplastic stroma in invasive squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 2.2). Although the regenerative squamous epithelium appears dark, basophilic-mimicking dysplastic epithelium, surface maturation remains evident from area to area, characterized by the increase of cytoplasm and lower nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. The nuclei are enlarged, but with smooth nuclear membranes, prominent nucleoli, and open chromatin. Mitoses are increased predominantly in the basophilic basal layer without any atypical mitoses (Figure 2.3). Dysplastic squamous cells or squamous cell carcinoma are architecturally disorganized and considerably more pleomorphic with hyperchromatic and overlapping nuclei, irregular nuclear contour, atypical mitoses, and the lack of surface maturation (Figure 2.4). Lastly, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may represent superficial manifestation of an underlying neoplasm, such as granular cell tumor. Granular cell tumor is a benign S-100 positive neurogenic tumor composed of cells with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, commonly associated with overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Figure 2.5). FIGURE 2.1 Regenerative squamous epithelium adjacent to ulceration (right) demonstrates elongated papilla, referred as “pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia.” The surface epithelium shows normal maturation. FIGURE 2.2 Irregular islands of invasive squamous cell carcinoma, composed of pleomorphic cells with high nuclear cytoplasmic ratio, in the background of desmoplastic stroma. FIGURE 2.3 Regenerative squamous epithelium with dark basophilic appearance, prominent nucleoli, and open chromatin. FIGURE 2.4 Dysplastic esophageal squamous epithelium with loss of polarity of the cells and pleomorphic nuclei. FIGURE 2.5 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying granular cell tumor of the esophagus. In the stomach, foveolar regenerative hyperplasia is a compensatory tissue response to the increased exfoliation of the surface epithelium. Atypia in regenerative foveolar epithelium often occurs associated with reactive/chemical gastropathy (usually nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug [NSAID]-induced), bile reflux, gastric ulcers, gastric hyperplastic polyps, gastric fundic gland polyps, and hamartomatous polyps (Figures 2.6–2.9). It is also a common finding at the squamocolumnar junction in gastroesophageal reflux (Figure 2.9). The regenerative compartment is at the gastric pit, which imparts tortuous or corkscrew-like appearance during an accelerated regenerative process (Figure 2.10). Mitosis is increased in the upper gastric pit. The immature foveolar cells appear basophilic with large vesicular nuclei and macronucleoli. Although disturbed, maturation of the foveolar epithelium toward the luminal surface remains present on close examination, characterized by the increase of clear apical cytoplasm and lower nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. The dark basophilic foveolar epithelium often mimics dysplasia, but dysplastic foveolar cells exhibit loss of polarization, hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei, low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, atypical mitoses at the luminal surface, and incomplete surface maturation (Table 2.1). These changes may mimic dysplastic epithelium (Figures 2.11 and 2.12) FIGURE 2.6 Basophilic short columnar regenerative gastric foveolar epithelium seen in various gastric diseases. FIGURE 2.7 Regenerative foveolar epithelium with various degree of surface maturation in the background of chronic inflammation. Some of the surface epithelial cells appear eosinophilic while others are dark basophilic. FIGURE 2.8 Atypical regenerative foveolar epithelium at the surface of gastric hyperplastic polyp. The foveolar cells show features of benignity, that is, low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. FIGURE 2.9 Inflammed gastroesophageal junctional mucosa with intraepithelial neutrophils. The foveolar cells show regenerative features and normal mitoses (arrows). Atypical regenerative epithelium in the intestine occurs in various eroded benign polypoid lesions, mucosal prolapse syndrome and polyps, and inflammatory bowel disease (Figures 2.13–2.16). Severe regenerative atypia is also often encountered in inflammatory bowel disease with severe disease activity or ulceration (Figures 2.17–2.20). The characteristics of regenerative intestinal epithelium generally are similar to those described earlier in the stomach mucosa. Careful examination of the rest of the intestine or comparison with biopsies from other segments of the intestine should provide baseline of normal epithelium, as it is uncommon for dysplastic or neoplastic mucosa to diffusely involve the intestine. Additional sections to confirm the presence of surface maturation are often required. FIGURE 2.10 Tortuous gastric pits with dark-stained short columnar regenerative foveolar eithelium in reactive/chemical gastropathy. TABLE 2.1 Histologic Features of Pseudocarcinomatous Epithelium/Atypical Regenerative Hyperplasia and High Grade Dysplasia/Carcinoma HISTOLOGIC FEATURES ATYPICAL REGENERATIVE HYPERPLASIA HIGH GRADE DYSPLASIA/CARCINOMA Nuclear pleomorphism +/− + Hyperchromatic nuclei − + Vesicular nuclei + − Irregular nuclear contour − + Pseudostratification +/− +/− Overlapping nuclei +/− + Surface maturation + − Loss of polarity +/− + Abnormal mitosis − + High nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio − + Desmoplastic stroma − +/− Myxoinflammatory stroma + − +, almost always present; +/−, can be present; −, almost always absent. FIGURE 2.11 Dark basophilic dysplastic epithelium with incomplete surface maturation in Barrett’s esophagus. FIGURE 2.12 High grade dysplastic surface epithelium with dark basophilic and pleomorphic nuclei, and high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. FIGURE 2.13 Dark basophilic crypt epithelium with superficial erosion in mucosal prolapse syndrome, mimicking neoplastic glands. FIGURE 2.14 Surface maturation with increased cytoplasm resulting in low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio remains evident in atypical regenerative epithelium. FIGURE 2.15 Dark basophilic regenerative crypt epithelium with nuclear crowding in previously ulcerated mucosa. The crypt epithelum in the right field appears more mature with an increased amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm and goblet cells. FIGURE 2.16 Normal mitoses (arrows) are commonly found in the deep crypt epithelium in regenerative mucosa. In addition, the deep crypt epithelium often appears more basophilic than the surface epithelium. FIGURE 2.17 Benign regenerative epithelium with various degree of surface maturation at the edge of the ulcer in ulcerative colitis showing overlapping of the nuclei and slight loss of polarization. FIGURE 2.18 Benign atypical regenerative epithelium at the edge of an ulcer exhibiting large prominent vacuolated nuclei with open chromatin. FIGURE 2.19 Dysplastic surface epithelium in inflammatory bowel disease. FIGURE 2.20 High grade dysplastic epithelium characterized by nuclear pleomorphism and loss of polarization, involving a nondysplastic crypt. Chemotherapy and radiation can result in diffuse toxic effects to the actively replicating gastrointestinal epithelium (Figures 2.21–2.24). The severity of mucosal injury varies from case to case and is usually more pronounced in the small intestine. The more common causes are antimetabolites, including fluoroxidin, 5-fluorouracil, or combination chemotherapy. 5-Fluorouracil is commonly used as an adjuvant in gastrointestinal malignancy. It interferes with DNA synthesis and RNA function. The morphologic changes include marked pleomorphism of the nuclei of the epithelial cells, mucin depletion, and cells that appear cuboidal in shape. The nuclei in crypt bases become pyknotic with karyorrhectic debris and lose their polarity. The surface epithelial cells become foamy or vacuolated and eventually undergo necrosis, producing mucosal ulceration. Mucosal regeneration occurs after cessation of therapy. These changes microscopically may mimic dysplastic epithelium or cancerization of the gastrointestinal epithelium; and considering the circumstances of chemotherapy, malignancy is always in the differential diagnoses. FIGURES 2.21 and 2.22 Chemotherapy-induced enteritis due to 5-fluorouracil showing pleomorphism of the nuclei of crypt epithelial cells, mucin depletion, and crypt dropout, which can mimic dysplastic crypts. FIGURE 2.23 Acute radiation-induced proctitis with marked pleomorphism of the nuclei of the crypts, crypt atrophy, and lamina propria edema. FIGURE 2.24 Exposed seminal vesicle glands at the base of a rectal ulcer after radiation to the prostate, mimicking adenocarcinoma. Another pseudocarcinomatous neoplastic mimic is endothelial cell proliferation at the ulcer bed. Plump epithelioid endothelial cells, forming capillaries with occasional mitoses that are obscured by inflammatory infiltrate, often mimic invasive adenocarcinoma (Figure 2.25). Immunohistochemical stains are helpful in confirming the nature of these cells. The endothelial cells are immunoreactive for vascular markers such as CD31, CD34, and Factor VIII antigen, and nonreactive to cytokeratins (Figure 2.26). FIGURE 2.25 Epithelioid endothelial cells (arrows) in the base of an ulcer may mimic glandular differentiation of carcinoma. FIGURE 2.26 CD34 immunostain confirms endothelial cells in newly formed capillaries. Benign inflammatory lesions with atypical stromal cells are found in many different organ systems including the upper respiratory tract, urinary bladder, and gastrointestinal tract. Although these cells represent “reactive” mesenchymal elements, such lesions can be easily mistaken for or mimic stromal tumor, sarcoma, or sarcomatoid carcinoma, due to the alarming cytologic atypia. In the gastrointestinal tract, sarcomatoid stromal cells can be encountered in the distal esophagus in patients with reflux esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus, as well as in gastric ulcers, eroded gastric hyperplastic polyps, inflammatory pseudopolyps from patients with inflammatory bowel disease, granulation tissue adjacent to surgical anastomoses, and hypertrophic anal papillae. The atypical cells range from widely scattered dendritic-shaped elements in a variably myxoinflammatory background, to closely packed groups of atypical spindle cells that are clustered along the base of an ulcerated mucosal surface (Figures 2.27–2.29). The cells often have a “ganglion-like” appearance with large, vesicular nuclei and macronucleoli. Unlike true sarcomas, they do not form solid clusters of cells and have a normal nucleus-to-cytoplasmic ratio. Immunohistochemical studies have shown that these atypical stromal cells were consistently immunoreactive for vimentin, occasionally reactive for smooth muscle actin, and negative for epithelial, endothelial, neural, melanoma, and lymphoma markers, which suggest fibroblastic or myofibroblastic differentiation. Although these results distinguish pseudosarcomatous proliferations from carcinoma, they offer little help in making a distinction between pseudosarcomatous proliferations to mesenchymal neoplasms, such as inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT), leiomyosarcoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Desmin and smooth muscle actin positivity are diagnostic of leiomyosarcoma, while c-kit and CD34 positivity are diagnostic of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (Table 2.2). The correct interpretation also requires integration of clinical, radiographic, and histologic observations. FIGURE 2.27 Scattered bizarre stromal cells (arrows) in the background of myxoinflammatory stroma with newly formed capillaries at the base of an ulcer. FIGURE 2.28 Many benign atypical stromal cells with large vesicular nuclei and macronucleoli at the base of an ulcer. FIGURE 2.29 Ulcerated gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Careful examination of the ulcer bed should also rule out the presence of underlying poorly differentiated or sarcomatoid carcinoma, lymphoma, and, lastly, cytomegalovirus inclusion in the endothelial and stromal cells of an immunocompromised patient (Figure 2.30). Confirmatory immunohistochemical stain for cytomegalovirus is often required as the infected endothelial and stromal cells are not easily distinguished from atypical stromal cells.

Neoplastic Mimics Common to the Entire Gastrointestinal Tract

PSEUDOCARCINOMATOUS REGENERATIVE AND INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

PSEUDOCARCINOMATOUS REGENERATIVE AND INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

PSEUDOSARCOMATOUS INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

PSEUDOSARCOMATOUS INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

INTRODUCTION

PSEUDOCARCINOMATOUS REGENERATIVE AND INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

PSEUDOSARCOMATOUS INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree