Although the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma has been refined during the past two decades, overall survival from this rather uncommon disease is still extremely poor. Here we review the current multimodal diagnostic and treatment options for patients with mesothelioma and discuss promising new experimental concepts in this disease.

Key points

- •

Mesothelioma is mainly linked to asbestos exposure, with a latency period of 20 to 40 years.

- •

The gold standard for diagnosis is thoracoscopy or thoracotomy. Chest radiograph, computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and serum mesothelin–related protein are useful clinical adjuncts.

- •

Surgical treatment is preferred for operable candidates—extrapleural pneumonectomy is better for locoregional control compared with pleurectomy/decortication, but both have similar overall rates of survival.

- •

Acceptable chemotherapy regimens include cisplatin or carboplatin with pemetrexed, with optimal survival seen in patients combining surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy.

- •

Currently there is no survival advantage with radiation therapy. Benefits include locoregional control of tumor burden and palliation of chest wall pain. Newer modalities are currently in trial.

Introduction

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare cancer of serosal surfaces with an annual incidence of 3300 new cases in the United States per year. It can affect the pleura, peritoneum, tunica vaginalis, and pericardium and is primarily linked to asbestos exposure. Ionized radiation, exposure to simian virus -40, and an autosomal-dominant gene in Turkish families have also been linked with development of mesothelioma.

Epidemiology

The incidence of disease in the United States reached its peak in 2000, consistent with a cancer latency period of 20 to 40 years from time of peak environmental asbestos exposure in the 1930s to 1970s. Epidemiologic studies reveal 3 cohorts of exposed patients. Immediate exposure to blue asbestos was demonstrably linked to development of mesothelioma during a large mining disaster in Wittenoom, Australia. Delayed exposure was linked to inhalation during the chain of manufacturing of asbestos-containing supplies. In 20% to 30% of cases, there is no known exposure , although some of these cases are genetically clustered as in some Turkish families. Interestingly, the remainder of the world did not follow America’s fierce reform of workplace asbestos exposure practices in the 1970s, and therefore the incidence of mesothelioma is expected to continue to rise in many developing and undeveloped countries.

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is hypothesized to occur in many ways. Blue asbestos fibers can directly irritate pleural surfaces, increasing the risk of malignancy. These fibers can also pierce mitotic spindles of cells and directly disrupt mitosis. Other explanations include DNA damage by production of iron-related reactive oxygen species as well as upregulation of MAP kinases and factors related to proto-oncogenesis. Additionally, simian virus-40 is a potent oncogenic cofactor and contributes greatly to pathogenesis of mesothelioma.

Histology and Staging

There are 3 primary histologic types of malignant mesothelioma: epithelial, sarcomatoid, and biphasic. Sixty percent to 70% of patients have epithelial cancers, demonstrating a best median overall survival of 17 months. These tumors are often confused histologically with adenocarcinoma, which may complicate and delay diagnosis. Twenty percent to 30% of patients have a biphasic histology that carries an intermediate prognosis of 6 to 17 months. Sarcomatoid tumors are rare (∼10% of patients) but aggressive with a poor median overall survival of less than 6 months. The 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging does not take into consideration these different histologic patterns but is still used to stage mesothelioma grossly and help partition patients into treatment algorithms and clinical trials ( Table 1 ). Other stratification algorithms are also commonly used. The Cancer and Leukemia Group assigns poor performance status, high levels of lactate dehydrogenase, anemia, chest pain, leukocytosis, and age greater than 75 as negative prognostic indicators. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer prognosticates and stratifies patients into clinical trials using poor performance status, leukocytosis, unclear diagnosis, male gender, and sarcomatoid histology as poor prognostic indicators. Modification has been championed by the International Mesothelioma Interest Group to account for stage-related prognostic variability, combining TNM with important histologic and clinical prognostic factors to partition cohorts of patients better for treatment.

| Tumor (T) | |

| T1 | Limited to ipsilateral parietal pleura |

| a | No involvement of visceral pleura |

| b | Involvement of visceral pleura |

| T2 | Involvement of ipsilateral parietal, mediastinal, diaphragmatic, and visceral pleura + involvement of at least the diaphragmatic muscle or the pulmonary parenchyma |

| T3 | Advanced but potentially resectable tumor as in T2, with involvement of at least one of the following: endothoracic fascia, mediastinal fat, a solitary focus of soft tissue in chest, or nontransmural extension into pericardium |

| T4 | Unresectable tumor with involvement of chest wall or extension into peritoneum, contralateral pleura, mediastinal organ, or spine |

| Node (N) | |

| N1 | Ipsilateral bronchopulmonary or hilar nodes |

| N2 | Ipsilateral subcarinal, mediastinal, internal mammary, or paradiaphragmatic nodes |

| N3 | Contralateral nodal involvement or ipsilateral and contralateral supraclavicular nodes |

| Metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

| Stage | T | N | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| a | T1a | N0 | M0 |

| b | T1b | N0 | M0 |

| II | T1-2 | N0 | M0 |

| III | T1-2 | N1-2 | M0 |

| T3 | N0-2 | M0 | |

| IV | T4 | Any N | M0 |

| Any T | N3 | M0 | |

| Any T | Any N | M1 |

Diagnosis

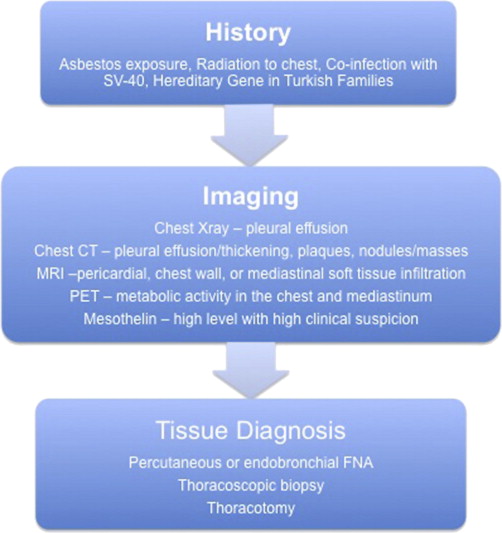

Most patients initially present for a workup for pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, constitutional symptoms of fatigue and weight loss, and a finding of pleural fluid on chest radiograph. Additional useful imaging modalities include computed tomography for the evaluation of the intrapleural space, lung parenchyma, and mediastinum, magnetic resonance imaging for involvement of chest wall and soft tissue, and positron emission tomography to evaluate for hypermetabolic activity suspicious of metastatic disease. Findings of a mass, interlobular thickening, and an associated pleural effusion (60% of effusions are on the right) on imaging are highly suspicious for malignancy. Conversely, findings of plaques (fibrous sheets) alone may reflect exposure to asbestos (benign asbestosis) but are not predictive of mesothelioma.

Fine-needle aspirate (FNA) is inconclusive in 20% of patients but can provide useful cytologic data. In cases of epithelial histology, FNA may incorrectly suggest adenocarcinoma; high suspicion should lead the clinician to evaluate further by immunohistochemistry staining for epithelial membrane antigen, calretinin, Wilms tumor 1 antigen, cytokeratin 5/6, or mesothelin, which are more commonly found in mesothelioma. When FNA biopsy is inconclusive, most clinicians proceed directly to thoracoscopic biopsy or, in rare cases, thoracotomy.

Fig. 1 illustrates an algorithm for the diagnosis of MPM.

Introduction

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare cancer of serosal surfaces with an annual incidence of 3300 new cases in the United States per year. It can affect the pleura, peritoneum, tunica vaginalis, and pericardium and is primarily linked to asbestos exposure. Ionized radiation, exposure to simian virus -40, and an autosomal-dominant gene in Turkish families have also been linked with development of mesothelioma.

Epidemiology

The incidence of disease in the United States reached its peak in 2000, consistent with a cancer latency period of 20 to 40 years from time of peak environmental asbestos exposure in the 1930s to 1970s. Epidemiologic studies reveal 3 cohorts of exposed patients. Immediate exposure to blue asbestos was demonstrably linked to development of mesothelioma during a large mining disaster in Wittenoom, Australia. Delayed exposure was linked to inhalation during the chain of manufacturing of asbestos-containing supplies. In 20% to 30% of cases, there is no known exposure , although some of these cases are genetically clustered as in some Turkish families. Interestingly, the remainder of the world did not follow America’s fierce reform of workplace asbestos exposure practices in the 1970s, and therefore the incidence of mesothelioma is expected to continue to rise in many developing and undeveloped countries.

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is hypothesized to occur in many ways. Blue asbestos fibers can directly irritate pleural surfaces, increasing the risk of malignancy. These fibers can also pierce mitotic spindles of cells and directly disrupt mitosis. Other explanations include DNA damage by production of iron-related reactive oxygen species as well as upregulation of MAP kinases and factors related to proto-oncogenesis. Additionally, simian virus-40 is a potent oncogenic cofactor and contributes greatly to pathogenesis of mesothelioma.

Histology and Staging

There are 3 primary histologic types of malignant mesothelioma: epithelial, sarcomatoid, and biphasic. Sixty percent to 70% of patients have epithelial cancers, demonstrating a best median overall survival of 17 months. These tumors are often confused histologically with adenocarcinoma, which may complicate and delay diagnosis. Twenty percent to 30% of patients have a biphasic histology that carries an intermediate prognosis of 6 to 17 months. Sarcomatoid tumors are rare (∼10% of patients) but aggressive with a poor median overall survival of less than 6 months. The 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging does not take into consideration these different histologic patterns but is still used to stage mesothelioma grossly and help partition patients into treatment algorithms and clinical trials ( Table 1 ). Other stratification algorithms are also commonly used. The Cancer and Leukemia Group assigns poor performance status, high levels of lactate dehydrogenase, anemia, chest pain, leukocytosis, and age greater than 75 as negative prognostic indicators. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer prognosticates and stratifies patients into clinical trials using poor performance status, leukocytosis, unclear diagnosis, male gender, and sarcomatoid histology as poor prognostic indicators. Modification has been championed by the International Mesothelioma Interest Group to account for stage-related prognostic variability, combining TNM with important histologic and clinical prognostic factors to partition cohorts of patients better for treatment.

| Tumor (T) | |

| T1 | Limited to ipsilateral parietal pleura |

| a | No involvement of visceral pleura |

| b | Involvement of visceral pleura |

| T2 | Involvement of ipsilateral parietal, mediastinal, diaphragmatic, and visceral pleura + involvement of at least the diaphragmatic muscle or the pulmonary parenchyma |

| T3 | Advanced but potentially resectable tumor as in T2, with involvement of at least one of the following: endothoracic fascia, mediastinal fat, a solitary focus of soft tissue in chest, or nontransmural extension into pericardium |

| T4 | Unresectable tumor with involvement of chest wall or extension into peritoneum, contralateral pleura, mediastinal organ, or spine |

| Node (N) | |

| N1 | Ipsilateral bronchopulmonary or hilar nodes |

| N2 | Ipsilateral subcarinal, mediastinal, internal mammary, or paradiaphragmatic nodes |

| N3 | Contralateral nodal involvement or ipsilateral and contralateral supraclavicular nodes |

| Metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree