Introduction

The essence of good geriatric practice is the expert management of the medical, psychological and social needs of elderly patients and their family caregivers. For this to be accomplished, the members of the interdisciplinary geriatric team—whether based in a hospital geriatric unit, an outpatient clinic, a nursing home, or a home-care programme—must work closely together to assess carefully the patient’s risks and problems and translate this knowledge into care plans that will have far-reaching effects on both the patient’s and caregiver’s lives.

Such multidimensional assessment implies the detailed investigation of the elderly individual’s total situation in terms of physical and mental state, functional status, formal and informal social support and network, and physical environment. This requires the clinician to become involved in collecting, interpreting, synthesizing and weighing a formidable amount of patient-specific information. Much of this differs in kind from the physical symptoms and signs, laboratory values, radiology results and other data that are traditionally combined to reach a medical diagnosis.

Definition

Multidimensional geriatric assessment (MGA) (often called comprehensive geriatric assessment or CGA) is a diagnostic process, usually interdisciplinary, intended to determine an older person’s medical, psychosocial, functional and environmental resources, and problems with the objective of developing an overall plan for treatment and long-term follow-up. It differs from the standard medical evaluation in its concentration on older people with their often complex problems, its emphasis on functional status and quality of life (QOL), and its frequent use of interdisciplinary teams and quantitative assessment scales.

As described in this chapter, multidimensional geriatric assessment can vary in its the level of detail, its purpose, and other aspects depending on the clinical circumstances. Therefore, multidimensional assessment denotes both the relatively brief multidimensional screening assessment for preventive purpose in a patient’s home as well as the interdisciplinary work-up of a newly hospitalized patient. Despite this broad definition, the term must meet the primary criteria above. For example, a multidimensional evaluation of an older person without link to the overall plan for treatment and follow-up does not meet these criteria. Similarly, a home visit emphasizing psychosocial and environmental factors, but not including a medical evaluation of the older person, is not a multidimensional assessment, since one of the key components of the multidimensionality is not included.

Rationale

While the principles of geriatric assessment may be valid in the treatment of younger persons as well, since bio-psycho-social factors play an important role in medicine for patients of all age groups, there is additional justification for using this multidimensional approach in older persons for various reasons:

- Multi-morbidity and complexity: Many older persons suffer from multiple conditions, and multidimensional assessment helps to deal with these complex situations through its systematic approaches and its setting of priorities.

- Unrecognized problems: Many older persons suffer from problems that have not been reported to the physician or may not even be known to the older person. One of the reasons problems may go undetected is that they may be falsely considered non-modifiable consequences of ageing. Multidimensional geriatric assessment is a method for identifying previously unknown problems.

- Chronic conditions: Many older persons suffer from chronic conditions. Diagnostic information without information on functional relevance of the underlying condition is often of limited value for therapeutic decisions or for monitoring follow-up.

- Interaction with social and environmental factors: Once functional impairments or dependencies arise, the older person’s condition is strongly influenced by his or her social and physical environment. For example, the arrangement of the older person’s in-home environment and the availability of his or her social network might determine whether a person can continue to live in his or her home.

- Functional status: One of the main objectives of medicine for older persons is to prevent or delay the onset of functional status decline. Epidemiological research has shown that functional status decline is related to medical, functional, psychological, social and environmental risk factors. Therefore, both for rehabilitation as well as for prevention the approach of multidimensional assessment helps to take into account potentially modifiable factors in all relevant domains.

- Intervention studies: Multiple intervention studies that compared the effects of programmes based on the concept of multidimensional geriatric assessment with usual care did show benefits of geriatric assessment, including better patient outcomes and more efficient healthcare use.

Brief History of Geriatric Assessment

The basic concepts of geriatric assessment have evolved over the past 70 years by combining elements of the traditional medical history and physical examination, the social worker assessment, functional evaluation and treatment methods derived from rehabilitation medicine, and psychometric methods derived from the social sciences.

The first published reports of geriatric assessment programmes came from the British geriatrician Marjorie Warren, who initiated the concept of specialized geriatric assessment units during the late 1930s while in charge of a large London infirmary. This infirmary was filled primarily with chronically ill, bedfast and largely neglected elderly patients who had not received proper medical diagnosis or rehabilitation and who were thought to be in need of lifelong institutionalization. Good nursing care kept the patients alive, but the lack of diagnostic assessment and rehabilitation kept them disabled. Through evaluation, mobilization and rehabilitation, Warren was able to get most of the long bedfast patients out of bed and often discharged home. As a result of her experiences, Warren advocated that every elderly patient receive comprehensive assessment and an attempt at rehabilitation before being admitted to a long-term care hospital or nursing home.1

Since Warren’s work, geriatric assessment has evolved. As geriatric care systems have been developed throughout the world, geriatric assessment programmes have been assigned central roles, usually as focal points for entry into the care systems. Geared to differing local needs and populations, geriatric assessment programmes vary in intensity, structure and function. They can be located in different settings, including acute hospital inpatient units and consultation teams, chronic and rehabilitation hospital units, outpatient and office-based programmes, and home visit outreach programmes. Despite diversity, they share many characteristics. Virtually all programmes provide multidimensional assessment, utilizing specific measurement instruments to quantify functional, psychological and social parameters. Most use interdisciplinary teams to pool expertise and enthusiasm in working toward common goals. Additionally, most programmes attempt to couple their assessments with an intervention, such as rehabilitation, counseling, or placement.

Today, geriatric assessment continues to evolve in response to increased pressures for cost-containment, avoidance of institutional stays, and consumer demands for better care. Geriatric assessment can help achieve improved quality of care and plan cost-effective care. This has generally meant more emphasis on non-institutional programmes and shorter hospital stays. Geriatric assessment teams are well positioned to deliver effective care for elderly persons with limited resources. Geriatricians have long emphasized judicious use of technology, systematic preventive medicine activities, and less institutionalization and hospitalization.

Components of Geriatric Assessment

A typical geriatric assessment begins with a functional status ‘review of systems’ that inventories the major domains of functioning.2–6 The major elements of this review of systems are captured in two commonly used functional status measures—basic activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). Several reliable and valid versions of these measures have been developed, perhaps the most widely used being those by Katz,7 Lawton8 and Barthel.9 These scales are used by clinicians to detect whether the patient has problems performing activities that people must be able to accomplish to survive without help in the community. Basic ADL include self-care activities such as eating, dressing, bathing, transferring and toileting. Patients unable to perform these activities will generally require 12- to 24-hour support by caregivers. Instrumental activities of daily living include heavier housework, going on errands, managing finances and telephoning—activities that are required if the individual is to remain independent in a house or apartment.

To interpret the results of impairments in ADL and IADL, physicians will usually need additional information about the patient’s environment and social situation. For example, the amount and type of caregiver support available, the strength of the patient’s social network, and the level of social activities in which the patient participates will all influence the clinical approach taken in managing deficits detected. This information could be obtained by an experienced nurse or social worker. A screen for mobility and fall risk is also extremely helpful in quantifying function and disability, and several observational scales are available.10, 11 An assessment of nutritional status and risk for undernutrition is also important in understanding the extent of impairment and for planning care.3 Likewise, a screening assessment of vision and hearing will often detect crucial deficits that need to be treated or compensated for.

Two other key pieces of information must always be gathered in the face of functional disability in an elderly person. These are a screen for mental status (cognitive) impairment and a screen for depression.2, 3, 6 Of the several validated screening tests for cognitive function, the Folstein Mini-mental State is one of the best because it efficiently tests the major aspects of cognitive functioning.3, 12 Of the various screening tests for geriatric depression, the Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale,13 and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale3 are in wide use, and even shorter screening versions are available without significant loss of accuracy.14

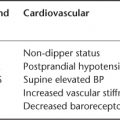

The major measurable dimensions of geriatric assessment, together with examples of commonly used health status screening scales, are listed in Table 112.1.2–16 The instruments listed are short, have been carefully tested for reliability and validity, and can be easily administered by virtually any staff person involved with the assessment process. Both observational instruments (e.g. physical examination) and self-report (completed by patient or proxy) are available. Components of them—such as watching a patient walk, turn around and sit down—are routine parts of the geriatric physical examination. Many other kinds of assessment measures exist and can be useful in certain situations. For example, there are several disease-specific measures for stages and levels of dysfunction for patients with specific diseases such as arthritis, dementia and parkinsonism. There are also several brief global assessment instruments that attempt to quantify all dimensions of the assessment in a single form.17, 18 These latter instruments can be useful in community surveys and some research settings but are not detailed enough to be useful in most clinical settings. More comprehensive lists of available instruments can be found by consulting published reviews of health status assessment.2–6

Table 112.1 Measurable dimensions of geriatric assessment with examples of specific measures.

| Dimension | Basic context | Specific examples |

| Basic ADL | Strengths and limitations in self-care,basic mobility and incontinence | Katz (ADL),7 Lawton Personal Self-Maintenance Scale,8 Barthel Index 9 |

| IADL | Strengths and limitations in shopping cooking, household activities, finances | Lawton (IADL)8 OARS, IADL Section 3, 4 |

| Social Activities and Supports | Strengths and limitations in social network and community activities | Lubben Social Network Scale16 OARS, Social Resources Section 3, 4 |

| Mental Health Affective | Degree of anxiety, depression, happiness | Geriatric Depression Scale 12, 14 Zung Depression Scale 3 |

| Mental Health Cognitive | Degree of alertness, orientation concentration, mental task capacity | Folstein Mini-mental State12 Kahn Mental Status Questionnaire 3, 4 |

| Mobility Gait and Balance | Quantification of gait, balance and risk of falls | Tinetti Mobility Assessment 10 Get up and go test 11 |

| Nutritional Adequacy | Current nutritional status and risk of malnutrition | Nutritional Screening Checklist 3 Mini-nutritional Assessement 15 |

| Special Senses | Hearing and vision impairments | Whispered Voice Test or Hearing Handicap Inventory 3–6 Snellen chart or Vision Function Questionnaire 3–6 |

| Oral Health | Impairments of oral health | Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index 5, 6 |

ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living

Settings of Geriatric Assessment

A number of factors must be taken into account in deciding where an assessment should take place—whether it is done in the hospital, in an outpatient setting, or in the patient’s home. Mental and physical impairment make it difficult for patients to comply with recommendations and to navigate multiple appointments in multiple locations. Functionally impaired elders must depend on families and friends, who risk losing their jobs because of chronic and relentless demands on time and energy and in their roles as caregivers, and who may be elderly themselves. Each separate medical appointment or intervention has a high time-cost to these caregivers. Patient fatigue during periods of increased illness may require the availability of a bed during the assessment process. Finally, enough physician time and expertise must be available to complete the assessment within the constraints of the setting.

Most geriatric assessments do not require the full range of technology nor the intense monitoring found in the acute care inpatient setting. Yet hospitalization becomes unavoidable if no outpatient setting provides sufficient resources to accomplish the assessment fast enough. A specialized geriatric setting outside an acute hospital ward, such as a day hospital or subacute inpatient geriatric evaluation unit, will provide the easy availability of an interdisciplinary team with the time and expertise to provide needed services efficiently, an adequate level of monitoring, and beds for patients unable to sit or stand for prolonged periods. Inpatient and day hospital assessment programmes have the advantages of intensity, rapidity and ability to care for particularly frail or acutely ill patients. Outpatient programmes are generally cheaper and avoid the necessity of an inpatient stay.

Assessment in the Office Practice Setting

A streamlined approach is usually necessary in the office setting. An important first step is setting priorities among problems for initial evaluation and treatment. The ‘best’ problem to work on first might be the problem that most bothers a patient or, alternatively, the problem upon which resolution of other problems depends (alcoholism or depression often fall into this category).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree