CHAPTER 7 Multicultural Medicine

Refugees and immigrants enter this country with knowledge, values, and behaviors about health, illness, and treatment that may be drastically different than those which underlie Western biomedicine and the American healthcare delivery system. Healthcare professionals must take on the potentially complicated tasks of diagnosing and treating these newcomers in manners that are appropriate and effective, overcoming barriers of language, concepts, and expectations. Though not all refugees or immigrants experience difficulties with the American medical system, the potential pitfalls for patients and providers are numerous.

Part A: General Concepts about Healing Systems

Cultures around the world and through time have created healing systems to respond to sickness and life-cycle changes such as pregnancy, birth, puberty, aging, and death. All healing systems have beliefs about what constitutes health, how the body functions normally, what happens to make it function abnormally, and what people can do to restore health.1–4

According to Sharma, there are three minimum requirements for a healing system: it must claim to be curative, have a systematized body of knowledge or theory, and a specified technical intervention that can be applied by an expert practitioner.5 These features are applicable to the healing systems in all cultures, irrespective of their origin or content, or whether they are primarily folk, traditional, or professional in nature. They apply to ancient systems, such as the Chinese traditional medicine, or modern, such as biomedicine. And they apply to healing systems with hundreds of millions of adherents, such as the Indian Ayurvedic system, or small healing systems whose devotees are counted in the hundreds, such as those in remote areas of Africa and South America.

Concepts of bodily functions, health, and disease

All healing systems have beliefs about what constitutes health and disease, and a coherent system of knowledge about how bodies function normally and abnormally.1–4 Understanding these may be a first step in gaining insights into health behaviors and forming therapeutic partnerships. For example, the traditional Indian system of Ayurvedic medicine is built on the ancient knowledge in the Atharvaveda text about the three humors – Vita, Pitta, and Kapha.6 Each person’s prescribed lifestyle of diet, exercise, and meditation is designed to maintain his or her specific balance between the three humors. Ayurvedic medicine has influenced other Asian systems, such as the Thai. The traditional Han Chinese system conceives of humans as being part of the universe that is modulated by the opposing yin and yang forces (male/female, hot/cold, wet/dry, dark/light), which are always changing.7,8 Health is maintained by balancing yin and yang forces and diseases are treated by restoring the balance. The Chinese traditional concepts of health and disease permeated other Asian healing systems, such as Vietnamese traditional healing, including the am/duong (or yin/yang) forces, and in turn had probably been influenced by them.9 Traditional Mexican beliefs of health include the importance of balancing hot/cold and wet/dry, concepts that probably were swayed by traditional concepts of the native peoples, such as the Mayan and Aztec, and by concepts brought to the New World by Spaniards whose practices had originated with Hippocrates’ theory of disease and the four humors.10,11

Every healing system has ideas about how natural, social, and supernatural aspects of life are related to health, illness, and healing.2 The natural realm describes the connections between people and the earth, such as dirt, water, air, plants, animals, etc. The social realm describes the connections between people of different ages, genders, lineages, and ethnic groups. And the supernatural realm describes the connections between the spiritual world and the human world and includes religious beliefs about birth, death, and the afterlife.

Healing systems are indivisible from the cultures in which they are present and are interwoven with other sociocultural elements ranging from familial relations to concepts of the universe.1–4 No connections or influences on health systems may be stronger than those of religion and spiritual beliefs.12 For example, Chinese medicine is interwoven with and influenced by Taoism, Ayurvedic medicine by Hinduism, and Tibetan medicine by Buddhism. Santeria healing rituals comes from Santeria, the syncretic religion formed from Yoruba gods and Catholicism, when Yoruba slaves in the West Indies were forbidden to practice their traditional religion but discovered their gods in Catholic saints. Similarly, people’s religious beliefs are intertwined with their interpretations and experiences of health and disease. The Islamic faith, for instance, teaches that all life events come from God or Allah, and that illness may be sent as a punishment, or an opportunity to atone for sins.13,14 Some Muslims believe that Allah has predetermined life events, and all statements about the future include the phrase Insha Allah, ‘If Allah wills,’ to acknowledge and accept God’s authority. Muslims try to endure their illnesses, and accept their experiences without losing faith or patience with God.

Theories of disease causation

Every healing system has explanations about etiologies. Determining causation has several functions: it guides therapy prospectively, confirms treatments retrospectively, and provides solace and meaning to human suffering. Helman organizes causations into four categories – individual, natural, social, and supernatural causes – with overlap between the categories.2 Some healing systems focus more on the individual and natural areas (such as biomedicine), while other systems know that all illnesses are ultimately caused by supernatural forces (such as the Azande). Still other systems examine the intertwined natural and supernatural reasons (such as Aztec, Haitian, Hmong, Mayan, and Yoruba). In the latter situations, people may identify a single cause for some illnesses, such as change in weather or a germ; for other illnesses, people may recognize an underlying supernatural cause, such as soul fright, which subsequently renders the person more vulnerable to a natural cause, such as a germ; while for other illnesses, particularly chronic life-threatening illnesses, people may suspect and address multiple causations over time.

Another method of categorizing disease causation distinguishes between ‘internal’ and ‘external’ etiologies.15 Internal etiologies refer to pathophysiological mechanisms in the body and identify proximate causes, i.e. what specifically caused the internal disorder or disease. Models for understanding proximate causation vary greatly from culture to culture. In Chinese traditional medicine, etiologies invariably involve alterations in the flow of energy or qi. In Western biomedical models, disease is usually the result of alterations or disorders of internal physiological homeostatic systems (e.g. electrolyte abnormalities or cancers) or the passage of external pathogens or mechanisms of disease and injury into the physical body (e.g. infectious agents, toxins, or bullets). Note that in the Western system, there is no disease state until such harmful items are ‘internalized,’ where they can disrupt homeostasis.

In contrast, external etiologies refer to mechanisms outside the body and identify the ultimate causes, i.e. what is the external root of the internal disorder or disease. These tend to focus on spiritual, religious, and philosophical reasons, such as ancestral spirits, divine providence, or fatalism. They may be the primary focus of concern, or may be an adjunct to help consider questions such as ‘why me?’ or ‘why now?’ In contrast, Western biomedicine has tended to ignore such topics. In some cultures, for example among the Azande in Africa, ultimate causation is often the dominant issue. As E. E. Evans-Pritchard discovered in the 1920s, if Azande people were cut while running down a path, the wounds were only part of their concern; they would hope to discover which spirit they had offended or who had bewitched them.16 Their focus was not on the specific and proximate mechanism of injury, but rather on the spiritual, or ultimate cause.

Classification of diseases

Each medical system classifies illnesses into discrete entities, similar to the manner in which biomedical professionals categorize diseases.2 Some systems have been carefully mapped out and written down, such as the Chinese and Ayurvedic systems. Others come from oral traditions, and have only recently been written, such as the Hmong in Laos, and Badaga in India. While all people may recognize abnormal bodily symptoms, such as diarrhea or fever, various healing systems classify them differently. For example, the Maya in Chiapas, Mexico, have eight types of diarrhea while an ethnic group in Mozambique has seven types of diarrhea.17 The Pakistani folk classification system describes several types of diarrhea, such that Pakistani mothers are more willing to use oral rehydration solution for some types of diarrhea than for others.18 In another example, Hmong have a disease classification system about childhood fevers with rashes (ua qoob) that differs from Western classification, which has caused conflicts between parents and providers about conducting septic evaluations of fever and about obtaining measles vaccinations in a measles outbreak.19

Different systems ascribe different names and different meanings to a disease, such that there may be no direct translations and no similar interpretations between systems. For Amharic people from Ethiopia, their traditional word for illnesses with jaundice such as hepatitis is yewof bashiyta, which means ‘bat disease,’ because jaundice was understood to be transmitted by bat urine when bats flew through the air in Ethiopia. To avoid this connotation, interpreters at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, WA, use the word gubbät or ‘liver disease’ when discussing hepatitis.20

Unique entities that are recognized by one healing system but not by others, particularly biomedicine, have been called folk-illnesses or culture-bound syndromes.2,21 Culture-bound syndromes have a specific cluster of symptoms, signs, or behavioral changes recognized by members of the cultural group, and responded to in a standardized way. They usually have a range of symbolic meanings – moral, social, or psychological – for both the victims and others around them. Culture-bound illnesses often link individual cases of illness with wider concerns, including victims’ relationships with the community, supernatural forces, antisocial emotions, and social conflicts, in a culturally patterned way. Ideally, the response to the illness can lead to the expression and resolution of these wider concerns.

The psychiatric Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version IV, includes categories for culture-bound syndromes, including Latino susto, Malaysian amok, and Laotian latah.22 However, folk illnesses can also pertain to physical conditions and not just to psychiatric conditions, including Latino empacho (abdominal pain attributed to intestinal blockage by food), ataques de nervios (attacks of nerves, caused by social anxieties), and caida de la mollera (fallen fontanelle caused by handling a baby roughly or pulling the breast out of an infant’s mouth quickly).23 Western societies are not immune to the attribution of culture-bound syndromes. Examples from the USA include high blood, colds, and chills, while the French may suffer from a particular type of liver pain (crise de foie).2 Like the other culture-bound syndromes that may seem more exotic to biomedical providers, each is identified as a unique disorder, mainly recognized and meaningful to individuals from particular cultures. Biomedical physicians may make psychiatric or medical diagnoses, such as psychosis, upper respiratory infection, appendicitis, heart attacks, or dehydration.

As folk illnesses are studied, it is apparent that some are not limited to one cultural group, but are shared by many cultures. For example, koro or genital shrinking is found among a wide range of Asian cultures; nervios is found in various Latino American and Mediterranean cultures; and evil eye has similar features between Latin Americans’ mal de ojo and the Arab’s evil eye.21 Similarly, neck pain and headache are routine among white collar employees and back pain among blue collar workers in many cultures around the world. While these may have pathophysiological ramifications, they also provide expression for personal, familial, communal, and social issues and forces. Other illnesses that start as folk illnesses, such as chronic fatigue syndrome and premenstrual syndrome, have become part of the biomedical lexicon, which entitles them to be designated as ‘true’ diseases worthy of medical treatment.

Interpretations of signs and symptoms

The question of how people know they are sick is far from simple. People’s interpretations of their bodily signs and symptoms are influenced by their healing system’s general concepts of normal and abnormal bodily functions, disease causation, and treatment options.2 People must first decide if a sign or symptom is normal or abnormal. For example, refugees and immigrants who are accustomed to seeing pus draining from children’s ears may not interpret draining ears as abnormal. Similarly, refugees and immigrants who are usually malnourished do not interpret obesity as a health problem, and those who are asymptomatic with hypertension or diabetes may not recognize they have a disease. If people decide their sign or symptom is abnormal, they must determine the meaning of the abnormality, and decide whether it’s trivial enough to ignore or important enough to label as a sickness.

People’s interpretations are based in individuals’ lived experiences and in their group’s cultural healing system. Kleinman24–26 calls people’s ideas about an illness their explanatory model (EM). Explanatory models have five aspects: timing and mode of onset of symptoms, pathophysiological processes, the etiology of the condition, natural history and severity of illness, and appropriate treatments. The sick person, family members, social network, and providers have their own explanatory models about the sickness event, which may be complementary or contradictory. Kleinman conceives that the more agreement between the patient, family, and provider’s explanatory models, the smoother their interactions are, while the more disagreement between the concepts, the more conflicts there are.

Treatment options – sectors of care

Treatments are closely linked to a healing system’s concepts of bodily functions, causation, and classification of diseases.2 For example, in Western biomedicine, specialists use medicines and operations to tackle physical diseases caused by proximate natural processes that work internally to disrupt bodily systems. In Chinese traditional medicine, therapies such as acupuncture and herbal medicines aim to rebalance energy flow that was disrupted by external natural or metaphysical forces.7,8 In Azande traditional systems, a spiritual healer divines the ultimate supernatural cause and sets about to eliminate that cause, such as by appeasing displeased spirits.16

Every society has a multiplicity of options for the treatment of diseases and illnesses as part of its healthcare system. This is true whether we speak about a village in the Kalahari Desert or the downtown area of any US city. Every healing system has medicines. Plants, animals, or earth materials are eaten, inhaled, worn, burned, or applied as poultices in order to soothe physical symptoms, restore metaphysical balance, ward away offending spirits, or bring inner peace and strength.27 Most systems also have physical therapies, such as Mexican abdominal massage to relieve empacho;28 Southeast Asian cupping, coining, and moxibustion to relieve built-up wind and bad blood;9 Chinese tai chi movements and acupressure to manipulate qi;7,8 and allopathic surgical interventions. Spiritual healing approaches are unique to each healing system’s connection with the spiritual world. Prayer, incantations, rituals, burning of incense, and sacrifice of animals are performed with different meanings and different interpretations in different religious traditions.27

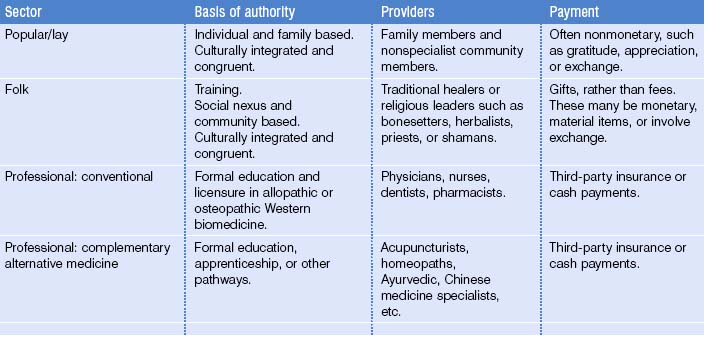

With the abundance of therapeutic options, both patients and providers need to define and categorize therapies. Kleinman describes three sectors of healers that are overlapping and interconnected: the lay or popular sector, the folk sector, and the professional sector (Table 7.1).25 In the lay sector, treatments are provided by family members or by the sick person, and may include medicines, massage, coining, cupping, burning, incantations, or wound dressings. The folk sector is comprised of healers that emanate from the secular or sacred ethnic or religious traditions (such as priests, shamans, or herbalists) and treatments generally require some sort of payment, whether money or gift. Many societies have professional medical personnel, including conventional allopathic and complementary/alternative medicine healers, where formal education and licensing are required and monetary payment is standard.

Healers from these three sectors may refer to each other, ignore each other, or compete with each other. In many societies, multiple folk healers exist side by side, providing generalized or specialized services. For example, among Arab Bedouin tribes in the Middle East, wise men or women with knowledge of traditional herbs may deal with simple ailments; amulet-makers tend to illnesses requiring more intensive or spiritual care; and dervishes are the ultimate authorities, reserved for more severe or recalcitrant cases.29

When refugees and immigrants arrive in this country, they bring along their traditional healers and healing methods. There may be barriers to the availability, accessibility, and affordability of these healing methods, from legal laws to financial barriers to structural constraints. But in every American community where immigrants and refugees settle, there are traditional herbalists, acupuncturists, masseuses, injectionists, ministers, midwives, magicians, or spiritual healers who are providing services to their ethnic group and to other populations as well. Mexican-American communities have access to traditional healers, such as curanderos who diagnose and treat natural illnesses with massage and herbal medicines that they grow or import from Latin America; yerberos who specialize in herbal medicines to prevent and treat illnesses; sobadors who treat bodily pain with massage; and brujos or brujas, sorcerers and witches, who treat supernatural illnesses with incantations and curses. In addition, there are botanicas, or shops that sell religious and spiritual products for healing.28,30

One might ask whether all these healing systems and options for care in the various sectors actual ‘work,’ i.e. demonstrate efficacy in terms of health and healing. The simple answer is ‘yes,’ but the reasons are complex.31 All cultural groups have had a vested interest in discovering the healing effects of their actions, and in passing along their knowledge to subsequent generations of healers. Generally, humans have discovered efficacious therapies over time, by objective and subjective evaluation, trial and error, and systematic observation, whether or not the tests were done by scientific principles. Indeed, the efficacy of some traditional therapeutics has been confirmed by modern scientific methods, such as aspirin from willow bark used by people from Assyria, Egypt, Greece, North America, and Sumer; quinine from bark of South American cinchona trees used by Native Americans; and acupuncture, acupressure, and tai chi from Chinese traditional medicine. In addition, all cultures have passed along their knowledge to new healers, whether or not their wisdom was written down or passed along orally.

Several other reasons are also relevant. One, most illnesses are self-limited and people either get better or die. Two, the placebo effect means that people’s desires to be healed and their beliefs in their system promote healing. Three, people tend to remember their successes rather than their failures. Four, failures support the system; patients are blamed for not following the treatment adequately or not seeking help soon enough; practitioners are blamed for not diagnosing the disease correctly or not administering the treatment accurately; the disease is blamed for being too strong; and spirits or fate or the impermanent nature of life are blamed for deaths.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree