The incidence of appendiceal tumors in the United States is approximately 2500 to 5000 cases per year.1,2 There are two major types of appendiceal neoplasms: nonepithelial neoplasms including neuroendocrine neoplasms (previously referred to as carcinoids) and epithelial neoplasms including mucinous adenocarcinomas, colonic-type adenocarcinomas, goblet cell carcinoids (adenocarcinoid), and signet ring cell carcinomas (Table 120-1). The carcinogenesis, tumor biology, clinical presentation, management, and oncologic outcomes differ among the various tumor subtypes mentioned above. The oncologic outcomes and management strategies for colonic-type adenocarcinomas and signet ring cell carcinomas of the appendix mimic their counterparts within the colon, and will therefore not be discussed in this chapter. Similarly, neuroendocrine neoplasms of the appendix will be considered in a separate chapter.

Appendiceal Tumors

| Neoplasms | Frequency (%) | Age (Years) | Gender | Lymph Node Involvement (%) | Peritoneal Metastasis (%) | Distant Metastasis (%) | 5-Year Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroendocrine neoplasms (carcinoid tumors) | 15 | 40 | Female (70%) |

| Rare |

|

|

| Mucinous adenocarcinomas | 40 | 50 | M ≅ F |

| 50–100 | HG-G3 = 10 |

|

| Colonic-type adenocarcinomas | 25 | 60 | M ≅ F | 30 | 5–10 | 20 | 55 |

| Goblet cell carcinomas (Adenocarcinoid) | 15 | 50 | M ≅ F |

|

| 12 |

|

| Signet ring cell carcinomas | 5 | 60 | M ≅ F | 60 | 10–15 | 60 | 25 |

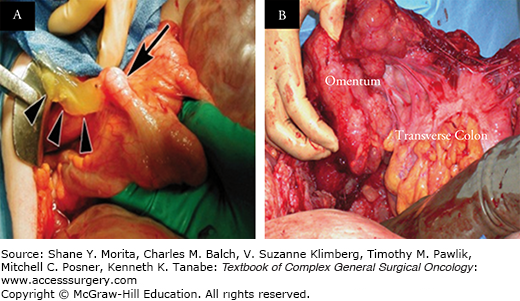

Mucinous appendiceal neoplasms (MAN) are characterized by abundant extracellular mucin comprising > 50% of the tumor volume. These neoplasms have a high tendency for peritoneal metastases, that may occur from rupture of a mucin-filled appendix harboring a MAN or following transmural invasion of mucin-secreting neoplastic cells from the primary tumor. Peritoneal metastases from MAN are referred to as pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP), a clinicopathologic entity that is characterized by accumulation of mucinous ascites and mucin-secreting neoplastic epithelial cells within the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 120-1).3,4 PMP of appendiceal origin is thought to be a malignancy of mucin-secreting neoplastic goblet-like cells, since goblet cells are the primary source of mucin production within the normal intestinal epithelium.5

FIGURE 120-1:

A. Ruptured mucinous appendiceal neoplasm (MAN) with dissemination of mucin into the peritoneal cavity (arrowheads represent extravasated mucin; arrow represents dilated appendix harboring a MAN). B. Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) with mucinous tumor deposits encasing the omentum and transverse colon.

According to recent Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) reviews, MAN account for approximately 40% of all appendiceal tumors (approximately 1500 cases/year). They are commonly diagnosed in the fifth and sixth decades of life and may have a slight female predisposition.1,2

Specific risk factors that predispose to the development of MAN have not been identified.

Genetic aberrations responsible for malignant transformation and progression of MAN are poorly understood. Similarly, molecular basis for the unique mucinous phenotype and variable histologic features of MAN remains unknown. KRAS gene mutations have been demonstrated in 41% to 100% of patients with MAN. Some reports indicate that KRAS mutation may increase mucin production and perhaps support progression to PMP, however no definitive correlation with oncologic outcomes has been demonstrated.6–10 GNAS gene mutations have recently been identified in 31% to 50% of low-grade MAN. Given the regulatory role of G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR)-cAMP-PKA signlaing pathway in epithelial secretion, GNAS mutations are likely related to the copious extracellular mucin identified in these tumors. In addition, frequent concurrent existence of GNAS and KRAS oncogene mutations has been implicated in the tumorigenesis of MAN and suggests that GNAS and KRAS are likely driver mutations in appendiceal mucinous neoplasia.11,12 Tumor suppressor gene TP53 overexpression, as defined by >10% nuclear staining for p53 protein on immunohistochemistry, has been demonstrated in 44% of patients with MAN, particularly in high-grade tumors, although its effect on survival is unclear.7,8 Maheshwari et al13 demonstrated loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in 61% of patients with PMP of appendiceal origin by analyzing polymorphic microsatellite markers situated at nine genomic regions in proximity to tumor suppressor genes suspected to undergo deletional changes in CRC including 1p36 (CMM/RIZ), 3p26 (VHL/OGG), 5q23 (APC), 7q31 (MET), 9p21 (CDKN2A/p16), 9q24 (PTCH), 10q23 (PTEN), 17p13 (TP53), and 18q21 (DCC and SMAD4/DPC4). A higher frequency of LOH was associated with high-grade MAN and deleterious outcomes in their study.13,14 LOH at 18q21 is more commonly identified in high-grade MAN than low-grade MAN, with loss of SMAD4 expression (tumor suppressor gene involved in TGFβ signaling) associated with poor overall survival.15Lastly, next generation exomic sequencing has identified concurrent MCL1 and JUN amplification in disseminated MAN.16

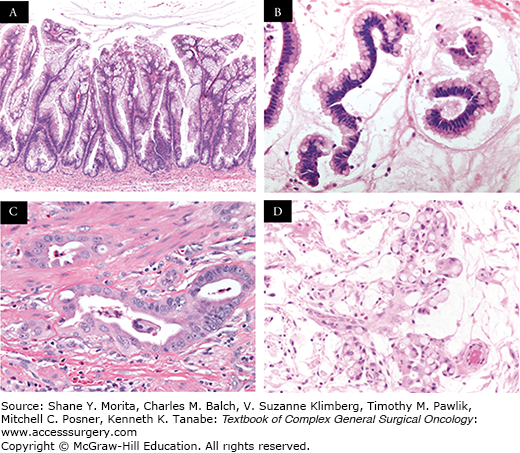

Mucinous appendiceal neoplasms commonly stain for MUC2 (100%), CK20 (95%), and CDX2 (75% to 98%) on immunohistochemical analysis. The histopathologic classification of MANs and their associated peritoneal disease has been a source of significant confusion and controversy in the literature (Fig. 120-2). Misdraji and colleagues17,18 used the term low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) to refer to appendiceal neoplasms with low-grade cytology, lacking destructive invasion of the appendiceal wall, regardless of the presence or absence of peritoneal dissemination; while they referred to neoplasms with high-grade cytology or destructive invasion of the appendiceal wall as mucinous adenocarcinoma (MACA). Pai et al19 modified the classification proposed by Misdraji by further subclassifying LAMN based on recurrence risk.19 MANs with low-grade cytology and which are confined to the appendix have no risk of recurrence and can be labeled mucinous adenomas, while LAMN with acellular mucinous deposits localized to the right lower quadrant have a low-risk (approximately 4%) of developing tumor recurrence and pseudomyxoma peritonei.20 LAMN with cellular mucinous deposits localized to the right lower quadrant had a high risk (approximately 40%) of developing tumor recurrence and full-blown pseudomyxoma peritonei. All recent classification schemes for MANs agree that the presence of any high-grade cytology or destructive invasion of the appendiceal wall warrants a diagnosis of mucinous adenocarcinoma (MACA).21–23

FIGURE 120-2:

A, B. Histologic sections (H&E staining) of a low-grade mucinous appendiceal neoplasm demonstrating abundant mucin; bland strips of mucinous epithelium; no significant mitotic activity, nuclear enlargement, or prominent macronucleoli; no complex architectural growth; and no infiltrative glands with stromal desmoplasia. C. Histologic section (H&E staining) of a high-grade mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma demonstrating destructive stromal invasion; complex growth architecture; stromal desmoplasia; increased cellularity with nuclear enlargement; and increased mitotic activity. D. Histologic section (H&E staining) of a signet ring cell appendiceal adenocarcinoma demonstrating similar features as a high-grade adenocarcinoma with the additional findings of signet ring cells.29

Pseudomyxoma peritonei may occur in the setting of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMNs) or mucinous adenocarcinomas (MACAs). Ronnett et al24 classified PMP into diffuse peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM), peritoneal mucinous adenocarcinoma (PMCA), and peritoneal mucinous adenocarcinoma with intermediate or discordant features (PMCA-I/D). However, Ronnett et al25 included mucinous neoplasms of colorectal origin in their analysis hindering the application of these diagnostic terms in appendiceal mucinous neoplasia. DPAM referred to a low-grade, indolent form of tumor with no cellular atypia, well-formed glands, no mitotic figures, and no invasive features and occurred exclusively in the setting of mucinous adenomas. These tumors have a good clinical prognosis after aggressive treatment with median survival of 112 months and 5-year survival rates of 75%. PMCA was characterized by severe cellular atypia, frequent mitoses, poor histologic differentiation, and tissue invasion, occurring in the setting of primary invasive appendiceal or colonic mucinous adenocarcinomas. The clinical course in these tumors mirrors that of other gastrointestinal tumors with peritoneal carcinomatosis, with median survival of 24 months and 5-year survival rates of 14% despite aggressive multimodality therapies. PMCA-I contained histopathologic features of both DPAM and PMCA, while PMCA-D demonstrated discordance between the primary tumor and the peritoneal nodules.24,25 Bradley et al26 attempted to simplify Ronnett’s classification of PMP into low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (MCP-L), encompassing DPAM and well-differentiated PMCA-I without signet-ring cells, and high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (MCP-H), encompassing MACA and PMCA-I with moderately or poorly differentiated features or signet-ring cells.

The majority of patients present with acute pain that on diagnostic workup is felt to represent simple appendicitis, peritonitis from ruptured appendicitis, or other acute gastrointestinal or gynecologic pathologies (30% to 50% of cases). Subsequent laparoscopy or laparotomy leads to the incidental diagnosis of MAN with or without peritoneal dissemination in these cases. Other common clinical presentations include progressive abdominal distention (25%), new onset of a hernia (15%), or palpable mass on abdominal or pelvic examination during routine examinations. Patients with low-grade MANs usually remain asymptomatic for years and present with compressive effects from slow accumulation of mucinous disease including abdominal distention and chronic pain. Conversely, patients with high-grade MANs often present earlier due to the invasive effects of the aggressive neoplastic cellular component of the disease including bowel obstructions, ureteral obstruction, and enteric fistulae.4,6,27

Since the majority of MANs have disseminated within the peritoneal cavity at the time of diagnosis, the utility of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system is limited. However, the seventh edition of the AJCC staging system separates mucinous from nonmucinous adenocarcinomas of the appendix since mucinous adenocarcinomas have a higher propensity for peritoneal dissemination and lower incidence of lymph node or visceral metastasis. In addition, tumor grade is a major prognostic factor in these tumors and the AJCC staging system utilizes tumor grade to distinguish stage IVA from IVB tumors (Table 120-2). Within the seventh edition AJCC grading system, grade 1 (G1) refers to well-differentiated low-grade tumors; grade 2 (G2) refers to moderately differentiated high-grade tumors; and grade 3 (G3) refers to poorly differentiated high-grade tumors.28 Unfortunately, the AJCC does not provide specific criteria that could be used to classify these three tumor grades, nor do they cite particular studies that could be used as a guide for tumor grading. Recently, Davison et al29 identified histologic features in MANs that were associated with worse overall survival on univariate analysis, including destructive invasion, high cytologic grade, high tumor cellularity, angiolymphatic invasion, perineural invasion, and signet ring cell component and then classified MANs into three grades: AJCC grade G1 lacked all adverse histologic features; AJCC grade G2 had at least one adverse histologic feature (except a signet ring cell component); and AJCC grade G3 was defined by the presence of a signet ring cell component. After controlling for other prognostic variables, AJCC grade G2 was associated with a 2.7-fold increased risk of death (95% confidence interval, 1.2 to 6.2) and AJCC grade G3 was associated with a 5.1-fold increased risk of death (95% confidence interval, 1.714) relative to grade G1 tumors.29 Similarly, Shetty et al30 stratified patients with MANs into three distinct survival categories by classifying these tumors into PMP-1 (peritoneal lesions with columnar, nonstratified epithelium without dysplasia or atypia and with abundant extracellular mucin); PMP-2 (focal or widespread epithelial atypia); and PMP-3 (any number of signet ring cells). They demonstrated median survival of 120 months (5-year survival 86%), 88 months (5-year survival 63%), and 40 months (5-year survival 32%) for patients with PMP-1, PMP-2, and PMP-3, respectively.30 The incidence of lymph node involvement increases with tumor grade: 1% for AJCC G1 tumors; 17% for AJCC G2 tumors; and 72% for AJCC G3 tumors.29

AJCC Staging System (Seventh Edition) for Appendiceal Carcinomaa

| Primary Tumor (T) | TX | Primary Tumor Cannot be Assessed |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Tumor (T) | T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ: intraepithelial or invasion of lamina propria | |

| T1 | Tumor invades submucosa | |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria | |

| T3 | Tumor invades subserosa or mesoappendix | |

| T4a | Tumor invades visceral peritoneum, including mucinous peritoneal tumor within the right lower quadrant | |

| T4b | Tumor directly invades other organs or structures | |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |

| N1 | Metastasis in 1–3 regional lymph nodes | |

| N2 | Metastasis in four or more regional lymph nodes | |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis | |

| M1a | Intraperitoneal metastasis beyond the right lower quadrant, including pseudomyxoma peritonei | |

| M1b | Nonperitoneal metastasis | |

| Histologic Grade (G) | GX | Grade cannot be assessed |

| G1 | Well differentiated/Mucinous low-grade | |

| G2 | Moderately differentiated/Mucinous high-grade | |

| G3 | Poorly differentiated/Mucinous high-grade | |

| G4 | Undifferentiated | |

| Anatomic Stage | Stage 0 | Tis/N0/M0 |

| Stage I | T1,T2/N0/M0 | |

| Stage IIA | T3/N0/M0 | |

| Stage IIB | T4a/N0/M0 | |

| Stage IIC | T4b/N0/M0 | |

| Stage IIIA | T1,T2/N1/M0 | |

| Stage IIIB | T3,T4/N1/M0 | |

| Stage IIIC | Any T/N2/M0 | |

| Stage IVA | Any T/N0/M1a/G1 | |

| Stage IVB | Any T/N0/M1a/G2,G3; Any T/N1,N2/M1a/Any G | |

| Stage IVC | Any T/ Any N/ M1b/ Any G |

Tumor grade and completeness of cytoreduction are the most important prognostic factors in MANs. Other factors that may have prognostic significance include preoperative tumor burden, prior chemotherapy, tumor marker levels, older age, time from diagnosis to surgical resection, postoperative morbidity rate, and lymph node involvement.6,14,30–36 As mentioned earlier, histologic features that offer prognostic information and may be used to stratify oncologic outcomes include destructive invasion, high cytologic grade, high tumor cellularity, angiolymphatic invasion, perineural invasion, and signet ring cell component.29,30 Based on a review of the SEER database, the 5-year disease-specific survival for MANs (58%) is equivalent to nonmucinous adenocarcinomas (55%).2 However, survival for MANs should be considered in the context of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion (CRS/HIPEC), performed at highly specialized referral centers, since this is now considered standard of care for these tumors. Outcomes following this aggressive approach may not be adequately captured by the SEER data. Analysis of institutional or multi-institutional data where CRS/HIPEC is routinely performed demonstrates median survival of 51 to 156 months and 10-year overall survival up to 70%. Moreover, 5-year survival rates for patients with low-grade tumors (PMP-1 or AJCC grade G1), intermediate-grade tumors (PMP-2 or AJCC grade G2), and high-grade tumors (PMP-3 or AJCC grade G3) are 86% to 91%, 61% to 63%, and 23% to 32%, respectively after CRS/HIPEC.29,30

Computed tomography imaging has been the main imaging modality used to evaluate the primary neoplasm and the disseminated peritoneal disease from MANs, demonstrating characteristic low-attenuation tumor material displacing or invading organ structures. More recently, however, MRI using combined diffusion-weighted and delayed gadolinium enhancement has been shown to be a superior modality for detecting and quantifying mucinous peritoneal tumor deposits. When compared to CT imaging, this MRI protocol is more sensitive and specific, demonstrates higher correlation with intraoperative peritoneal cancer index, and is especially beneficial for evaluating extent of disease along the small bowel mesentery which is a major determinant of resectability (Fig. 120-3).37 The diagnosis of MANs is suspected when mucinous ascites is encountered at paracentesis or at the time of diagnostic laparoscopy. Tissue biopsy may be achieved by percutaneous, laparoscopic, or open techniques. Tumor markers including CEA, CA 19-9, or CA-125 are elevated preoperatively in 50% to 75% of patients and may offer some prognostic information.14,38

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree