Monitoring During Treatment

INTRODUCTION

The treatments administered to patients with gynecologic cancers are among the most complex in a radiation oncologist’s practice. Treatment of gynecologic cancers requires multidisciplinary collaboration, integration of multiple treatment modalities, and complex specialized radiation therapy (RT) techniques. The use of highly conformal external beam techniques requires close monitoring of radiation setup accuracy, organ motion, and tumor response. Brachytherapy, a component of treatment for many gynecologic cancers, often requires detailed advance planning to assure that patients are ready for the treatment. In addition, in many cases, radiation is used for definitive treatment of tumors that cause pain, bleeding, urinary tract compromise, or other symptoms; the optimal management of tumor and treatment-related side effects is an important component of high-quality care.

Careful monitoring during RT is essential and includes several components:

Consideration of social circumstances, nutrition issues, and coexisting medical conditions that could influence treatment of the cancer

Monitoring progress toward completion of the treatment plan to avoid delays

Evaluation and management of acute treatment-related adverse effects

Evaluation of the accuracy of daily treatment setup

Monitoring of changes in body habitus and tumor response and preparation for sequential treatments including external beam boosts or brachytherapy

SOCIAL CIRCUMSTANCES, NUTRITION, AND COEXISTING MEDICAL CONDITIONS

Social circumstances, nutrition issues, and preexisting medical conditions can have major influences on patients’ ability to tolerate and complete treatment of gynecologic malignancies. Whether or not these conditions are directly related to the cancer, they must be addressed from the onset of treatment for patients to have the best possible outcome.

Social Circumstances

Social and financial stresses frequently make it difficult for patients to complete 6 to 8 weeks of RT in a timely manner. Young single mothers and elderly women with disabled spouses can have difficulty managing the demanding schedule of chemoradiation. Victims of sexual or spousal abuse can have particular difficulty dealing with pelvic examinations and other invasive procedures. In patients with social circumstances that could jeopardize the success of treatment, an early social services consultation can be critical to a good outcome.

Nutrition Issues

Poor nutrition can result from social circumstances, from the side effects of combined modality treatments, or from the cancer itself. Patients should always be closely monitored for weight loss, which is often the first sign of dehydration or poor nutritional intake. Most patients with nutrition issues benefit from consultation with a dietician who can counsel

them on dietary adjustments to help control diarrhea, nausea, and weight loss.

them on dietary adjustments to help control diarrhea, nausea, and weight loss.

Coexisting Medical Conditions

For patients receiving complex treatments involving concurrent chemoradiation and brachytherapy, coexisting medical conditions can be major barriers to optimal care. The radiation oncologist must be aware of any condition that could influence the course of treatment, including those listed in the following paragraphs.

Cardiopulmonary Disease

Cardiac, respiratory, and other conditions that could influence the patient’s ability to undergo brachytherapy should be evaluated early in the patient’s course of RT to optimize the patient’s condition prior to invasive procedures and to avoid delays in treatment. Patients with pacemakers and cardiac defibrillators require assessment by a cardiologist and close monitoring during RT to confirm that treatment does not cause these devices to malfunction.

Diabetes Mellitus

Even well-managed diabetes can become uncontrolled when corticosteroids are administered with chemotherapy. Management of diabetes can be complicated by adverse effects of cancer treatment, including nausea, anorexia, and changes in diet. Patients should be reminded to monitor their blood glucose level closely during this time. Close collaboration with the patient and with her medical oncologist and internist can reduce the risk of serious diabetes-related complications. In some cases, a reduction in the corticosteroid dose or even suspension of corticosteroid use may be necessary to manage brittle diabetes.

Deep Venous Thrombosis

Patients with cancer have an increased risk of developing deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus. Patients with gynecologic cancers are at particularly high risk because bulky pelvic wall disease (which can obstruct venous flow; CS 11.8), pelvic lymphadenectomy, and prolonged immobility are all risk factors for clot formation. A new finding of peripheral edema, particularly if it is unilateral, should be evaluated promptly. Because clots often originate in the pelvis, peripheral Doppler studies may not detect the source of obstruction; pelvic imaging may be required to make a diagnosis. Patients who have a pulmonary embolus may present with hypoxia but often have less specific symptoms such as sudden onset of profound fatigue or tachycardia; these symptoms should be evaluated immediately. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest according to a pulmonary embolus protocol is usually used to confirm or rule out pulmonary embolus. If an embolus is confirmed, anticoagulation, usually with enoxaparin sodium (Lovenox), is required.

Need for Anticoagulation

Patients who will require brachytherapy and are receiving anticoagulants should be evaluated early to determine whether their medications will need to be adjusted prior to brachytherapy. If necessary, intracavitary applicator placement can be performed carefully while patients are receiving therapeutic doses of anticoagulants. However, whenever possible, patients who are taking warfarin, aspirin, or antiplatelet agents such as clopidogrel should have the drug held for 5 days prior to invasive procedures; reversible anticoagulation therapy with enoxaparin sodium or heparin can be administered and then stopped 12 hours prior to the procedure. Interstitial implants should not be placed while patients are receiving warfarin, clopidogrel, or similar anticoagulants.

MONITORING PROGRESS TOWARD COMPLETION OF THE TREATMENT PLAN

Before treatment is started, the overall treatment plan should be clearly articulated, and there should be clear communication between the members of the multidisciplinary team to confirm the details of the treatment plan and the start date.

Once treatment begins, the plan should be reviewed weekly to determine the following:

Is the patient receiving chemotherapy as planned? If not, why not? Are members of the multidisciplinary team aware of the RT schedule, particularly as it affects the delivery of concurrent chemotherapy?

Is the patient receiving radiation treatments on schedule? If not, why not? How can the delay be addressed?

What are the most recent laboratory results? How are any abnormalities being addressed?

Is the patient losing weight? Is she receiving adequate nutrition?

Have necessary arrangements been made to facilitate planned external beam or brachytherapy boosts?

Have any tumors or treatment-related adverse effects been adequately addressed?

Delays in RT should be avoided whenever possible; an effort should always be made to assure that the average weekly dose is at least 850 cGy per week. Radiobiologic principles and extensive clinical data1,2 indicate that treatment protraction allows proliferation of surviving cells, increasing the risk of local recurrence. Although some investigators have suggested that treatment protraction may be less harmful for patients treated with concurrent chemoradiation,3 these suggestions have been based on studies that were far too small to rule out clinically significant increases in recurrence rates caused by treatment protraction. Although there have been no adequately powered studies in patients receiving chemoradiation, a 2008 review of Gynecologic Oncology Group chemoradiation trials suggested a deleterious effect of treatment protraction.4 Concurrent chemotherapy has reduced but not eliminated in-field recurrences, and there is no reason

to believe that concurrent chemotherapy eliminates proliferation of surviving clonogens, some of which may be resistant to chemotherapy. If concurrent chemotherapy were sufficiently effective to reduce the recurrence risk to negligible levels, it would actually be more beneficial to reduce the dose of radiation, thereby decreasing the risk of late adverse effects, than to unnecessarily protract treatment.

to believe that concurrent chemotherapy eliminates proliferation of surviving clonogens, some of which may be resistant to chemotherapy. If concurrent chemotherapy were sufficiently effective to reduce the recurrence risk to negligible levels, it would actually be more beneficial to reduce the dose of radiation, thereby decreasing the risk of late adverse effects, than to unnecessarily protract treatment.

In our experience, nearly all treatment breaks and delays are medically unnecessary and should therefore be avoided. The following steps can eliminate most delays:

At the beginning of treatment, discuss with the patient the importance of not missing treatments. Ask the patient about transportation, dependent care, and other challenges to adherence to the prescribed schedule and enlist social services to work with the patient if necessary.

Plan each step of treatment in advance to avoid delays related to planning or scheduling of boosts.

Manage treatment-related adverse effects proactively.

If concurrent chemoradiation causes depression of blood cell counts, RT should be continued even if chemotherapy has to be interrupted.

If the patient has missed more than 2 days of treatment because of holidays or other reasons, attempt to schedule b.i.d. treatments (usually separated by a 6-hour interval) to make up some or all of the missed treatments (CS 10.1).

EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE TREATMENT-RELATED ADVERSE EFFECTS

Most patients receiving RT for gynecologic cancers experience tumor- or treatment-related adverse effects.

Adverse Effects of RT by Treatment Location

The acute adverse effects of RT are directly related to the region treated.

True Pelvis

The most common adverse effect of pelvic RT is diarrhea, which usually worsens gradually over the course of treatment. Dysuria, usually associated with urinary tract infection (UTI), is less common. Skin reactions are rare unless patients are treated with anteroposterior-posteroanterior fields or have skin folds or vulva included in the high-dose region. Patients who are treated for gross cervical, vaginal, or vulvar disease may experience a foul-smelling discharge as the tumor responds to RT. Nausea is rare if treatment is confined to the pelvis and is not accompanied by chemotherapy.

Paraaortic Region

The most common adverse effect of irradiation of the paraaortic region is nausea, sometimes accompanied by belching and heartburn. Radiation-related nausea can have an abrupt onset, typically 30 to 60 minutes after RT. Diarrhea is infrequent and usually mild if treatment is confined to the paraaortic region.

Distal Vagina and Vulva

The most common symptoms of irradiation of the distal vagina and vulva are erythema and desquamation associated with pruritus and pain. Vulvovaginitis may cause dysuria or pain on defecation. As discussed below, the severity of local symptoms can be significantly lessened with local care and infection control.

Adverse Effects of Chemotherapy

Today, RT for gynecologic cancers is frequently administered with concurrent chemotherapy, usually cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Although other members of the multidisciplinary team administer the chemotherapy, the radiation oncologist is typically on the front line when patients coming for daily treatment develop symptoms. Therefore, radiation oncologists must be aware of the drugs being administered with radiation, understand the adverse effects of these drugs, and be prepared to treat symptoms as they occur. Acute and long-term side effects of chemotherapy are also discussed in Chapter 3.

Diarrhea

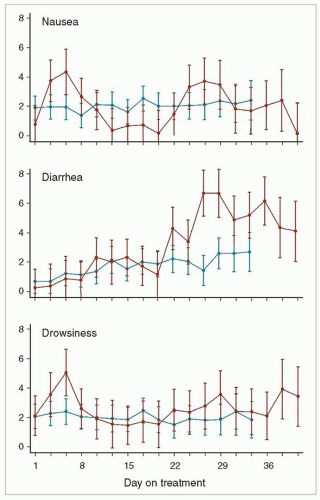

Most patients receiving pelvic RT experience at least mild diarrhea, usually beginning in the 3rd or 4th week of treatment. In severe cases, patients may have eight or more watery bowel movements per day; these symptoms can contribute to electrolyte disturbances and even dehydration. Diarrhea is often accompanied by lower abdominal crampy pain. Hemorrhoid flare-ups can contribute to the patient’s discomfort. Patients who are receiving concurrent chemotherapy tend to have more severe diarrhea than patients treated with radiation alone, and concurrent multiagent chemotherapy may cause more severe diarrhea than weekly cisplatin (Fig. 7.1).

Patients who have very severe diarrhea, particularly early in the treatment course, should be evaluated to rule out another contributing factor, particularly infection with Clostridium difficile. Patients who have recently received intravenous antibiotics in the hospital are at particularly high risk for C. difficile infection (CS 12.1). In some cases, presumptive treatment with metronidazole may be warranted while cultures are in process.

Treatment and positioning techniques that minimize the dose of radiation to bowel can reduce the severity of diarrhea (Chapter 6). For patients who still experience symptoms, dietary management, and carefully titrated administration of antidiarrheal medications can usually control symptoms. Pretreatment counseling and a staged approach to medical management, as outlined in the following paragraphs, are important components of symptom management.

Before Treatment

Before treatment, ask patients about their bowel habits and food sensitivities and advise patients to avoid any food that tends to cause diarrhea. Lactose intolerance tends to become more severe or may first become apparent during RT. Therefore, patients who have a history of lactose intolerance should be advised to avoid milk products during treatment.

Advise patients who are constipated to continue their laxative regimens as necessary, but counsel them that their medications will probably need to be modified as treatment progresses. Encourage patients to request guidance when their bowel habits begin to change. Advise patients to obtain loperamide to have on hand in case diarrhea develops suddenly.

Counsel patients to contact you immediately if symptoms are not well controlled. A visit with the radiation oncologist on Friday can avoid a weekend emergency room visit.

During Treatment

Ask patients about their bowel habits at each visit. A good way to estimate symptom severity is to ask, “How many bowel movements did you have, what was the consistency, and how many loperamide or diphenoxylate and atropine (Lomotil) pills did you take yesterday? the day before?”

Increase the use of antidiarrheals as needed. The following guidelines are recommended:

Initially, 1 pill after each loose bowel movement up to 8 pills per day.

If the patient requires more than 3 to 4 pills per day for 2 or more days, ask about the timing of diarrhea and suggest a schedule that anticipates the symptoms. The following regimen can be very effective:

One pill left on the bedside table at night taken as soon as the patient awakens in the morning

One pill 20 to 30 minutes before lunch

One pill 20 to 30 minutes before dinner

One pill at bedtime

If diarrhea occurs between these intervals, an additional pill (loperamide or diphenoxylate and atropine) can be taken, or the dose can be increased to 2 pills at each time point.

The total number of loperamide pills should not exceed 8 per day, but in rare cases of refractory diarrhea, up to 8 diphenoxylate and atropine pills can be added to this.

In cases of very refractory diarrhea, other medications, such as tincture of opium or paregoric, can help, but such medications are very rarely necessary.

Manage the patient’s diet. Patients should reduce intake of dietary fiber and any food that has caused diarrhea in the past. Foods that frequently exacerbate diarrhea are raw fruits (particularly pitted fruits and watermelon), salad greens, beans, onions, and spicy or greasy foods. In some cases, caffeinated beverages can stimulate diarrhea. A dietician should be consulted if one is available.

Monitor patients for weight loss. Sudden loss of more than 3% to 4% of the body weight usually is a sign of dehydration. Examine patients for orthostatic symptoms, decreased skin

turgor, and dry mucous membranes. Check electrolyte levels. Give patients intravenous fluids if necessary. Management of late radiation enteropathy is discussed in Chapter 9.

turgor, and dry mucous membranes. Check electrolyte levels. Give patients intravenous fluids if necessary. Management of late radiation enteropathy is discussed in Chapter 9.

At the End of Treatment

Counsel patients that in most cases, diarrhea resolves completely within 4 to 6 weeks of the end of treatment, although some patients may continue to have episodes of diarrhea beyond this period. Advise patients to proceed gradually when reintroducing previously avoided foods. Loperamide can be taken as needed.

Nausea, Vomiting, and Anorexia

Radiation-Induced Nausea

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree