The safety of liver surgery made great strides in the last half of the twentieth century thanks to an improvement in the knowledge of hepatic anatomy, perioperative care, and preoperative imaging techniques.1 Combined with increased operative experience and technological advancements, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) of the liver has been shown to be safe and feasible with over 3000 cases done worldwide.1–4 Laparoscopic hepatic surgery was first reported in the early 1990s, and since that time the literature in this field has expanded in an exponential fashion.2 The acceptance of MIS hepatic resections has progressed to the point where it is the recommended approach for certain hepatic resections5 and as our experience broadens, as do the potential indications. Increasingly complex procedures are being safely performed and achieving excellent results with less morbidity. In the present chapter, we provide an overview of laparoscopic liver resection including some technical aspects, and outcomes of minimally invasive hepatic resection for cancer.

For the purpose of this chapter, an MIS hepatic resection is a general term that includes purely laparoscopic, hand-port assisted laparoscopic, hybrid, and robotic-assisted approaches. Purely laparoscopic is the most commonly reported approach, followed by hand-assisted resections.2 Hybrid resection refers to laparoscopic-assisted open resections, where a portion of the procedure is performed laparoscopically, typically the mobilization of the liver, followed by the parenchymal transection done through a small open incision, typically the extension of the hand-port incision, if present.6,7 While infrequently reported in the literature, this approach may be an attractive option for surgeons wishing to adopt laparoscopic hepatic resections into their practice6 and is potentially associated with improved perioperative outcomes.8 Robotic resections are restricted by the increased cost of the procedure, but confer some advantages to the operating surgeon including improved dexterity and visualization.9–11 Other reported approaches include gasless laparoscopic as well as thoracoscopic hepatic resections. As there aren’t any prospective trials comparing the different techniques in MIS liver surgery, the approach is individualized based on tumor characteristics as well as surgeon preference and experience.

The indications for MIS hepatic resections have evolved as our experience grows. While initially described for small nonanatomical resections, major hepatic resections have been reported with increasing frequency and trisectionectomies have been described in certain specialized centers.8,12–15 As the application of MIS techniques to liver surgery has expanded, a consensus conference was convened in 2008 and involved the leading experts on the topic in order to address the developing questions and issues around the subject. The International Position on Laparoscopic Liver Surgery was published, and recommended that current acceptable indications for laparoscopic resections included solitary lesions of 5 cm or less located in segments 2 to 6.5 While it is generally accepted that these lesions are the most amenable to MIS techniques,1 the consensus statement did include the caveat that all liver resections can be performed using MIS in experienced hands. They also added that the laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy (LLS) should be considered standard practice.5 Not surprisingly, nonanatomic resections or segmentectomies are the most common reported MIS hepatic resection, followed by LLS.2

Indications for MIS liver surgery include benign and malignant diseases. A minimally invasive technique lends itself well to the treatment of benign hepatic lesions. In fact, it is recognized as the preferred approach to the resection of giant symptomatic hepatic cysts,16 and has been successfully utilized in the treatment of other benign liver lesions.2 Although it has been suggested that referrals have increased for laparoscopic liver resection of benign lesions,17 the consensus was that indications should not be expanded beyond those of open hepatic resection simply due to the advent of a MIS approach.5

As malignancies are the most common indication for hepatic resections, it comes as no surprise that MIS resections for malignant tumors and indeterminate lesions are increasingly frequent.2 Hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) and colorectal cancer liver metastases (CRCLM) are the most commonly reported malignant indications for MIS liver surgery, with other tumors being far less common.2,18

Another indication for MIS liver surgery is laparoscopic live donor hepatectomy for liver transplant. This was initially reported using laparoscopic LLS for pediatric transplants;19 this has since been reported in adults using hemi-hepatectomies.20–22 Obviously, this needs to be performed in centers that specialize in both advanced laparoscopic techniques and live donor transplants, limiting the applicability and widespread acceptance of these procedures.21,23

The main contraindications for MIS liver surgery include any contradiction to liver surgery or pneumoperitoneum, as well as tumor factors such as the size and the proximity to major vessels. These factors are evaluated on a case-by-case basis by the operating surgeon, whose training, experience, and discretion will dictate the ability to perform the resection in a minimally invasively fashion.

The evaluation for MIS liver resections follows a similar course to that of open surgery. A general evaluation of the ability to tolerate major surgery via a thorough history and physical and ancillary tests as needed is required. This is accompanied by a thorough evaluation of hepatic function, as this will dictate the extent of surgery that individual patients will tolerate. This is accomplished using clinical and laboratory parameters and scoring systems such as the commonly used Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) or the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores. While not universally agreed upon, a functional liver volume of at least 25% should be left behind in patients with normal liver function,24 40% in patients with high-grade steatosis, and greater than 50% in patients with cirrhosis.25 Volumetric assessments of the future liver remnant using CT or MRI allow for objective and accurate measurements and are useful tools for the operating surgeon. In patients who require an extended resection, portal vein embolization can be a useful tool in increasing the size of the future liver remnant.26

An evaluation of portal hypertension should also be undertaken. A history or radiological evidence of varices or the presence of significant preoperative thrombocytopenia is commonly used as markers of portal hypertension. Independent of tumor burden, CTP or MELD score, it has been shown that major morbidity, postoperative liver insufficiency, and mortality are increased when significant portal hypertension is present.27,28

Cross-sectional imaging in the form of a triple-phase CT scan or a contrast-enhanced MRI is imperative for the evaluation of hepatic lesion(s) and for operative planning. The surgeon will use these to evaluate the plane and the extent of resection. Consideration is given to the structures that will be removed, while leaving adequate vascular inflow, as well as hepatic venous and biliary outflow to the remaining liver. At this time, based on patient, tumor, and surgeon factors, an evaluation of whether an MIS liver resection is appropriate can be performed.

With some exceptions, the operative steps involved in MIS hepatic surgery mirror those of its open counterpart. Just like any procedure, steps are performed in an orderly fashion in order to efficiently perform the operative goals and to minimize complications (Table 125-1). The first step is to safely and efficiently gain access to the abdominal cavity and insufflate the abdomen. This can be achieved with a number of well-described techniques, the most common being an open Hasson technique, or through a closed technique using a veress needle. Additionally, optical-access trocars can be used for direct visualization while entering the abdominal cavity. The authors prefer the Hasson approach, as it allows for a direct visualization of the entry into the abdominal cavity, although the evidence suggests that the complication rates are similar.29,30

Once in the abdomen, the next steps are to mobilize the liver and to complete a sonographic evaluation of the liver, which is required to confirm the preoperative diagnosis and to rule out other pathology. This is particularly important in totally laparoscopic procedures, as tactile assessment of the liver is not possible. In fact, it has been suggested that intraoperative hepatic ultrasonography is superior to transabdominal ultrasound and computed tomography and as effective as magnetic resonance imaging to detect hepatic lesions.31,32

After evaluating the hepatic anatomy and tumor location, the surgeon proceeds to inflow control, parenchymal transection, and outflow division as required for the planned resection. These three steps are mentioned together as the order that they are performed depends on the type of resection to be undertaken as well as surgeon experience and preference. For nonanatomical resections, inflow control and outflow division may not be necessary. Numerous options exist for parenchymal transection, including laparoscopic ultrasonic dissectors, energy devices, clips, and ties,5 but our preferred method is to use a combination of an electrosurgical device and staplers to safely divide the liver. Following this, the resected liver can be extracted and hemostasis achieved.

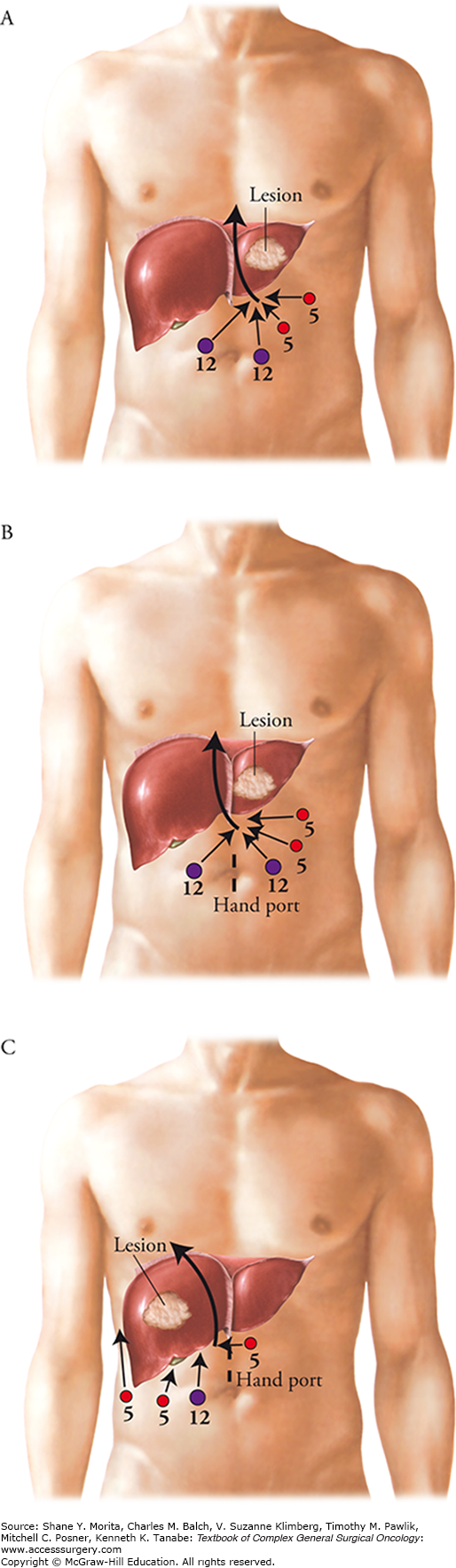

In order to better illustrate how these procedures are performed, we present our approach to three commonly performed MIS liver resections: the totally laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy, the hand-assisted right hepatic hemi-hepatectomy, and the hand-assisted left hemi-hepatectomy.

The totally laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy is performed with a four-trocar technique as outlined in Fig. 125-1A. The liver is mobilized by the incision of the falciform and left coronary ligaments using a hook electrocautery device. The round ligament is divided with a stapler at the level of the abdominal wall, allowing us to use it as a handle for retraction. The laparoscopic ultrasound is then used to evaluate the entire liver for synchronous lesions as well as to confirm the location of the tumor and the plane of transection required for its safe removal. Retracting the round ligament superiorly, the bridge connecting segments III and IVb, if present, is exposed and divided using a LigaSure sealing device. The left porta hepatis is dissected at the base of the umbilical fissure to identify and divide the left hepatic artery between locking hemoclips, taking care to preserve the branch to the left medial sector. Parenchymal transection is then initiated using the LigaSure device just to the left of the falciform ligament to a depth of 2 to 3 cm to avoid major vascular pedicles. At this point, the segment III and II portal pedicles that contain the corresponding portal vein, hepatic artery, and hepatic duct are isolated within the parenchyma by creating tunnels with an atraumatic dissector. The segment II and III portal pedicles are then divided inside the liver using vascular load staplers. The remaining parenchyma is divided approaching the left hepatic vein inside the liver. The left hepatic vein is carefully thinned out allowing a final stapler to safely transect this structure. Hemostasis is then achieved along the cut edge of the liver using a TissueLink monopolar or bipolar saline-linked hemostatic sealer. The specimen is then removed through an EndoCatch bag and a JP drain may be placed at the surgeon’s discretion.

Use of a hand port during laparoscopic liver resection has advantages and disadvantages, and is up to the discretion of the surgeon. Advantages include tactile evaluation of the liver, access for bleeding control if required, and ease of mobilization and retraction during major resections.14,33 Additionally, it can be used as the extraction site for the resected liver. Disadvantages include a larger incision, interference by the hand to limit visibility, and the risk of incisional hernia. For a left hepatic hemi-hepatectomy, we place the hand port in a periumbilical midline location in addition to four trocars as outlined in Fig. 125-1B. The mobilization and ultrasonic evaluation are performed in an identical fashion to that described in the previous section. The surgeon may choose to encircle the hepatic hilum with a vessel loop for vascular control with a Pringle maneuver as needed. The round ligament is once again retracted superiorly in order to fully expose the left porta hepatis. The left hepatic artery is divided between locking hemoclips and the left portal vein is dissected, encircled, and either divided or clamped with a bulldog. Retracting the left lateral segment to the right exposes the ligamentum venosum, which is divided to separate the left and caudate lobes. A cholecystectomy is performed and the plane of transection is marked with a hook electrocautery device along Cantle’s line. The ultrasound is then used to confirm an adequate resection margin and to identify the location of the major vascular structures that will be encountered. Hepatic parenchymal transection is started using the LigaSure device, and the crossing segment IV feedback vessels as well as the middle and left hepatic veins are divided using a vascular stapler. If not already divided, the left portal vein and hepatic duct are taken at the hilar plate once the liver has been “open-booked” using the stapler. Hemostasis on the cut-edge is achieved, and the specimen is placed in an EndoCatch bag and removed through the hand port.

For a right hemi-hepatectomy, the hand port is placed in a supraumbilical midline location (Fig. 125-1C). The right triangular and diaphragmatic ligaments are taken down and the liver is retracted to the left, allowing the visualization of the inferior vena cava and the short hepatic veins. Small short hepatic vein tributaries (<3 mm) can be sealed and transected with the LigaSure device, while larger veins should be secured with hemoclips. This is continued up to the base of the right hepatic vein. Although the right hepatic vein can be divided in an extrahepatic fashion, it is our preference to divide this last inside the liver parenchyma to minimize the risk of inducing a bleed from the junction of the right hepatic vein with the inferior vena cava. A cholecystectomy is then performed, and attention is given to the hilar dissection. The cystic artery typically leads to the right hepatic artery, which is isolated and divided between locking hemoclips. The right portal vein is then dissected and either divided or controlled with a bulldog clamp. Similarly to the left hemi-hepatectomy, the resection line is marked and verified with the ultrasound. Parenchymal transection is then performed with the LigaSure device. Care is taken to divide the crossing middle hepatic vein branches with vascular stapler, followed by the right portal vein and right hepatic duct at the hilar plate once the liver is opened. The right hepatic vein is divided last inside the liver close to the inferior vena cava. Hemostasis is achieved and the specimen is placed in an EndoCatch bag and removed through the hand port.

While laparoscopic resections of small peripheral lesions are more commonly performed, the adoption of MIS techniques to major anatomic resections has been much slower owing to a fear of uncontrolled hemorrhage. However, recent studies have shown excellent results for laparoscopic major hepatectomy in experienced hands.8,13,15,34,35

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree