Surgery plays a central role in the treatment of mid-stage gastric cancer (T2-T4a, N0-N3a). Chemo- or chemoradiotherapy before and/or after surgery may improve survival, but adequate and meticulous surgery is a prerequisite for cure of the disease. Optimal local tumor control is achieved with gastric resection having sufficient resection margins and adequate lymphadenectomy. In this section, the principles and techniques of standard gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for noncardiac distal gastric cancer are described.

Mid-stage distal gastric cancer is treated with either distal gastrectomy or total gastrectomy. In distal gastrectomy, two-thirds or more of the stomach is usually removed. Selection of gastrectomy depends on the tumor location and the mode of infiltration in the stomach wall, and proximal resection margin is the main determinant. A 5-cm margin has traditionally been recommended, and the ESMO guidelines1 advocate 8 cm for diffuse type cancer. According to the Japanese treatment guidelines,2 on the other hand, a 5-cm margin is recommended for tumors showing an infiltrative growth pattern with indistinct borders or diffuse-type histology, but 3 cm is usually sufficient for those showing an expansive growth pattern with grossly distinct borders for which the histology is most frequently of the intestinal type. Frozen section diagnosis is useful to confirm negative resection margins.

It was once argued that all gastric cancers should be treated by total gastrectomy. Theoretically, total gastrectomy ensures more certain negative margins and sufficient lymphadenectomy. However, it is associated with a higher operative morbidity and mortality, increased risk of long-term nutritional problems, and impaired quality of life as compared to distal gastrectomy. The policy of total gastrectomy “de principe” was abandoned after randomized trials comparing total and distal gastrectomy in distal gastric cancer failed to show a survival benefit.3

Lymph node metastasis is the most common mode of spread in gastric cancer. As the tumor invades deeper, the incidence of lymph node metastasis becomes higher: it is roughly estimated that 3%, 20%, 50%, and 80% of T1a, T1b, T2/3, and T4a/T4b tumors, respectively, have histological lymph node metastasis. The stomach is the organ that has the largest number of “regional lymph nodes” in human body, and its minimal number of examined nodes for adequate nodal staging defined in the TNM Classification is the largest. Unlike other distant metastases, lymph node metastasis from gastric cancer can be surgically removed for potential cure as long as it is confined to the regional area. However, intraoperative gross diagnosis of lymph node metastasis is quite unreliable, especially in gastric cancers of diffuse type histology, and thus systematic “prophylactic dissection” with optimal chance of removal of involved lymph nodes has been sought.4

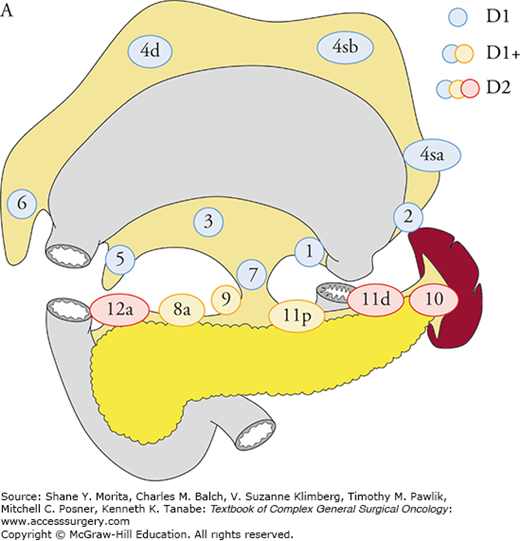

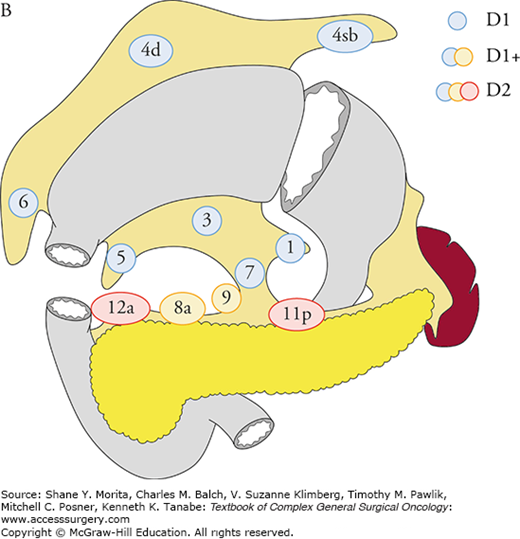

Based on the analyses of large database of potentially curative resections, the Japanese Classification5 and the Treatment Guidelines2 defined D1, D1+, and D2 lymphadenectomy for total and distal gastrectomy, and recommend D2 lymphadenectomy in mid-stage gastric cancer (Figs. 97-1A, B). The ESMO1 and the NCCN guidelines also recommend D2 lymphadenectomy in curative gastrectomy by experienced surgeons in high-volume centers. More extended D2 plus para-aortic nodal dissection (PAND) was compared with D2 in a well-designed randomized controlled trial in Japan, which failed to show a survival benefit of PAND.6

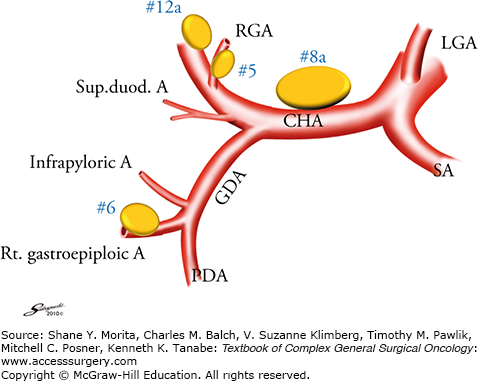

FIGURE 97-1

The extent of lymphadenectomy is defined according to the type of gastrectomy. For each type, complete dissection of lymph nodes in blue circles is D1, and dissection less than D1 is D0. Complete dissection of the nodes in blue and yellow circles is D1+, and that of the nodes in blue, yellow, and red circles is D2. In total gastrectomy for tumors invading the esophagus, the lower mediastinal nodes are also included in D1+ and D2. A. Definitions of lymphadenectomy (D) in total gastrectomy. B. Definitions of lymphadenectomy (D) in distal gastrectomy. (Reproduced with permission from Japanese Gastric Cancer Association: Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3), Gastric Cancer. June 2011;14(2):113–123.)

Most of the following descriptions, by the same authors, have been published in another textbook.7

Mobilization of the duodenum facilitates a safe and smooth procedure for the subsequent infrapyloric lymphadenectomy. The peritoneum close to the duodenum should be incised and the incision extended along the duodenum. The pancreatic head covered by the retropancreatic fascia is mobilized from the retroperitoneal space. The para-aortic area should be palpated and, if suspicious nodes exist, they should be sampled. A rolled gauze is placed behind the pancreatic head to raise the pancreas and facilitate the further procedure.

Though omentectomy is not necessarily a part of D2 dissection, it is usually performed for T3/T4 tumors to remove possible tumor spread in the omenta. The omentum is removed from the right side of the transverse colon and the duodenum, then dissected along the transverse colon toward the lower pole of the spleen. When omentectomy is omitted, the incision line of the omentum should be at least 3 cm away from the right gastroepiploic arcade so that the lymph nodes along the arcade (No 4d) are completely dissected.

Omentobursectomy is the complete removal of the lesser sac (omental bursa) that consists of the omenta, the anterior sheet of the transverse mesocolon, and the pancreatic capsule. It has been performed in potentially curative gastrectomy with the aim of removing possible cancer seeding inside the bursa. As it increases morbidity related to pancreatic fistula, it is no longer a standard procedure even in Japan. A randomized controlled trial recruiting 1200 patients is now active in Japan to evaluate its impact on survival.

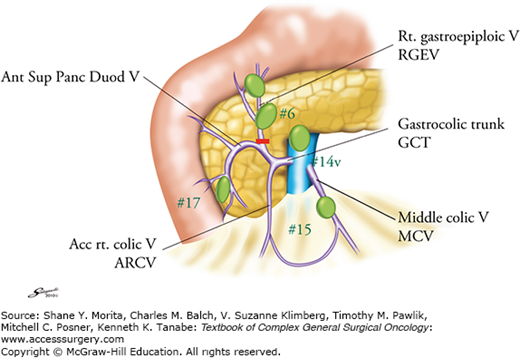

Infrapyloric lymph nodes (No. 6) are those along the first gastric branch and proximal part of the right gastroepiploic artery (RGEA) down to the confluence of the right gastroepiploic vein (RGEV) and the anterior superior pancreatoduodenal vein (ASPDV). In distal gastric cancers, a precise dissection of No. 6 lymph nodes is essential because they are most frequently involved but still the dissection of positive nodes is consistent with a curative intent procedure.

For precise lymphadenectomy in this area, detailed knowledge of vascular anatomy, especially of the venous network, is essential. The assistant should hold the transverse colon and gently stretch the mesocolon. The middle colic vein should be identified and pursued, and the gastrocolic venous junction point exposed. The accessory right colic vein (ARCV), RGEV, gastrocolic trunk, and ASPDV are identified. Occasionally, the RGEV and ARCV separately drain into the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) without forming the gastrocolic trunk. The middle colic vein usually drains directly into the SMV.

The RGEV should be ligated and cut prior to its junction with the ASPDV. A small vein draining from the pancreas to the RGEV should be carefully cauterized. When No. 6 nodes are grossly metastatic, dissection of the nodes in front of the SMV (No. 14v) should be considered.

Then, the gastric antrum should be pulled up and the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) identified between the duodenum and the pancreas. The GDA is exposed distally as far as the origin of the RGEA. The infrapyloric artery arises near the origin of the RGEA. The RGEA and the infrapyloric artery should be ligated and cut together or separately at their origin.

The GDA should be pursued proximally to its origin from the common hepatic artery (CHA) (Fig. 97-3). A large, flat lymph node (No. 8a) usually covers the CHA. The peritoneum covering this node is opened at the right edge of the node, and the surface of the CHA exposed. Using this procedure, No. 5 (supra-pyloric nodes along the proximal part of the RGA) and No. 8a nodes are separated. A gauze pad is placed to the right of the No. 8a node on the surface of the CHA, which will serve as a landmark of the correct layer in the subsequent suprapyloric dissection.

FIGURE 97-3

Branches of the common hepatic artery and lymph node numbers. The supra- and infrapyloric lymph nodes and those along the common hepatic artery are frequently involved in antral tumors and should be precisely dissected. Sup. duod. A, superior duodenal vein; RGA, right gastric artery; CHA common hepatic artery; LGA, left gastric artery; GDA, gastroduodenal artery; PDA, pancreatoduodenal artery; SA, splenic artery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree