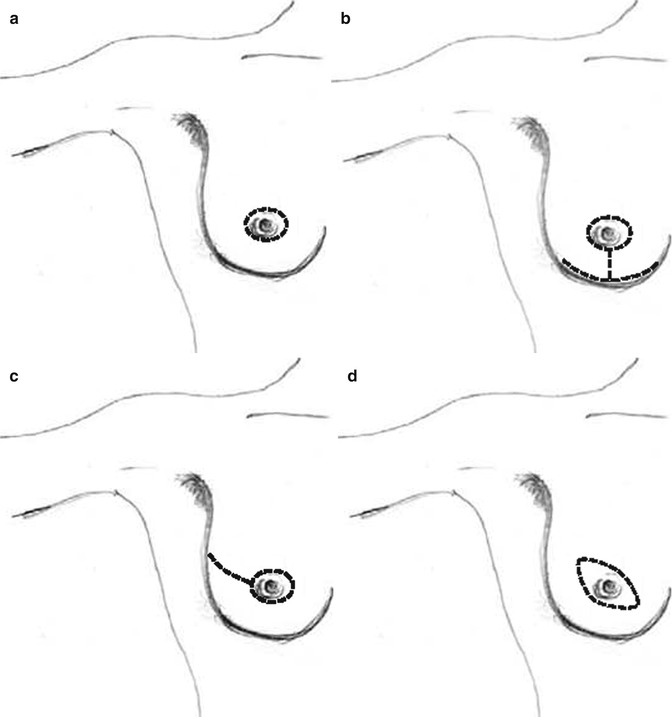

Fig. 14.1

Oblique elliptical incision for simple mastectomy

An incision is made through the dermis and the skin is elevated using penetrating skin hooks. A dissection plane is developed in the avascular plane between the breast parenchyma and the subcutaneous tissue ensuring preservation of the subcutaneous vasculature. The dissection proceeds utilizing electrocautery as necessary or with a scissors or knife depending on surgeon preference. The mastectomy skin flaps are then created, allowing removal of all breast parenchyma while leaving a layer of subcutaneous fat. Acceptable flap thickness varies by patient and amount of subcutaneous fat present. Skin flaps should not be so thin as to compromise blood supply and lead to skin necrosis. However, creating flaps that are too thick will leave behind breast tissue that may lead to an increased risk of tumor recurrence.

Once the skin flaps have been dissected superiorly to the clavicle, inferiorly to the inframammary fold, medially to the sternal border, and laterally to the latissimus dorsi, the breast is removed from the pectoralis major muscle. Elevation of the breast from the pectoralis major is usually performed with electrocautery. The superior margin of the breast is grasped and retracted caudad, while the pectoralis fascia is removed with the breast leaving the underlying pectoralis major muscle intact. At times when the tumor is abutting or invading the pectoralis muscle, this area of muscle can be removed with the specimen. Perforating vessels should be controlled with electrocautery, clips, or ties. As the dissection progresses inferolaterally, care is taken to preserve the fascia of the serratus muscle. Toward the axillary tail, the lateral mammary branches entering the breast are ligated and divided. The breast is divided at the axilla, which is recognized by visualization of the clavipectoral fascia.

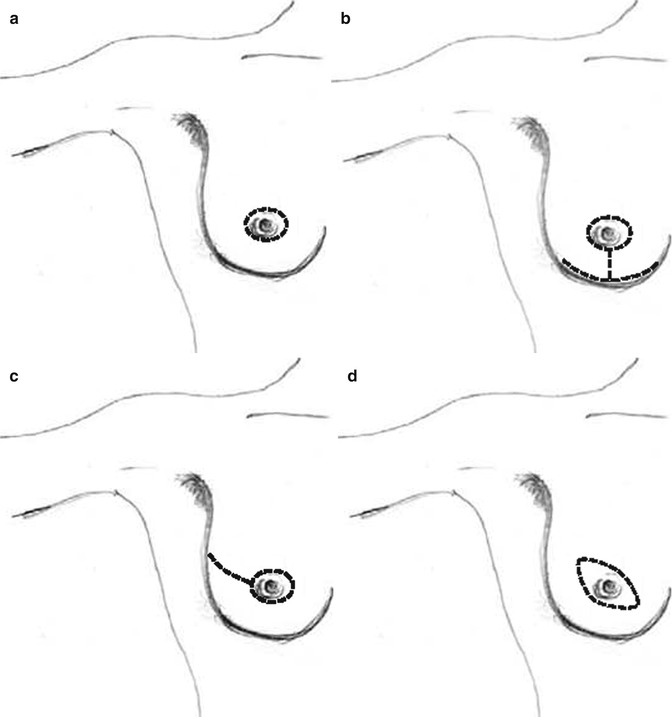

Skin-Sparing Mastectomy

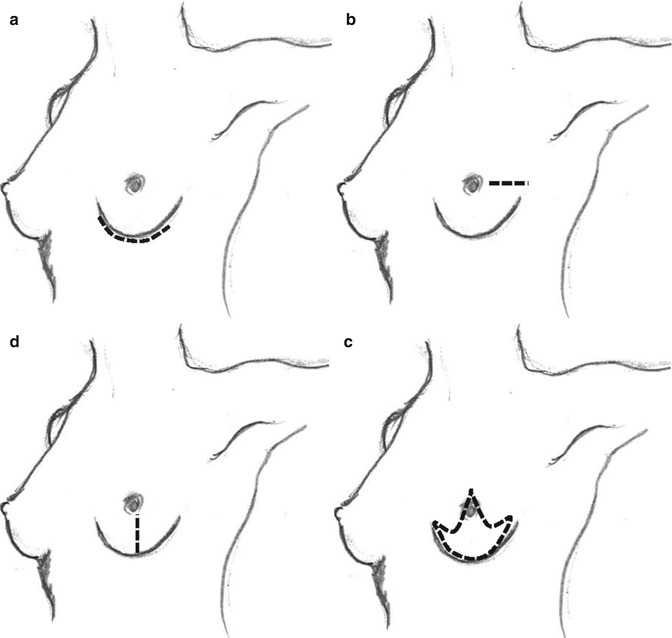

The skin-sparing mastectomy as described by Toth and Lappert [18] achieves removal of all breast parenchyma with the nipple-areola complex and minimal skin excision (figure 14.2). This technique is well suited for patients who are having immediate tissue or implant reconstruction.

Fig. 14.2

Skin-sparing mastectomy incisions: (a) peri-areolar, (b) reduction, (c) tennis racquet, (d) modified ellipse

Nipple-Areola-Complex-Sparing Mastectomy

First described in the 1960s by Freeman [19] as the subcutaneous mastectomy, the nipple-areola-complex (NAC)-sparing mastectomy was intended to achieve an improved cosmetic result by preserving the NAC. This procedure was initially performed selectively at very few institutions, as there were concerns for oncologic outcomes as well as appropriate selection criteria. In women undergoing prophylactic mastectomy, nipple-areola-sparing mastectomy is well accepted as a safe procedure. There remains controversy regarding its use in women with invasive cancer. However, an increasing body of evidence supports nipple-areola-sparing mastectomy in select patients. This includes women who have small (<3.5 cm), peripherally located tumors that are >2 cm from the nipple, a negative axilla and have not been treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy [20–23]. Frozen sections are routinely sent in patients with invasive cancer or DCIS to confirm a negative nipple margin before proceeding with nipple-areola-sparing mastectomy. In our experience, the overall rate of nipple involvement was 10.6 % [24].

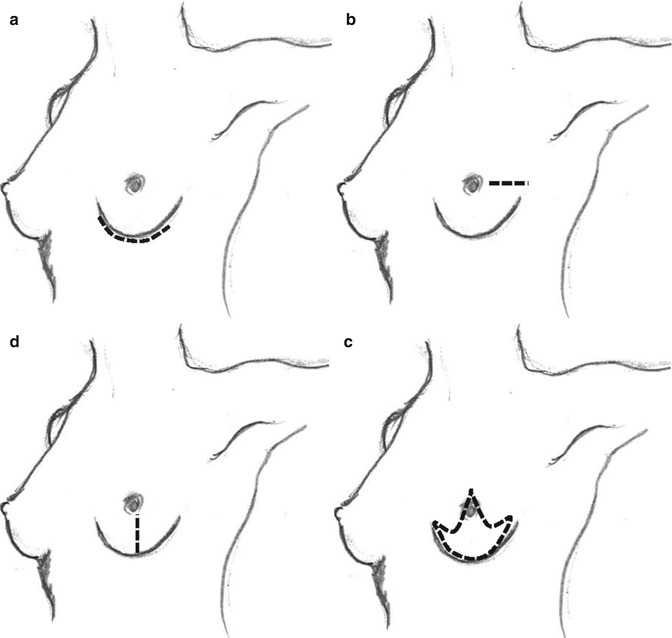

There are several incisions that can be used for the NAC-sparing mastectomy, including the inframammary fold, various lateral incisions, vertical incision, and an incision that incorporates a reduction mastectomy (Fig. 14.3). The choice of incision is largely predetermined by the size of the breast as well as the extent of ptosis. A well-placed incision facilitates removal of all breast parenchyma within the boundaries of a traditional mastectomy. In women who present with small, non-ptotic breasts, this can be done through an inframammary incision. However, in the larger ptotic breast, a variation of the lateral or vertical incision is better suited for performing an oncologically safe procedure with survival of the breast skin.

Fig. 14.3

Nipple-areola-complex-sparing incisions: (a) inframammary, (b) lateral, (c) vertical, (d) reduction

Once the skin incision has been made, flaps are raised in the usual fashion. The creation of skin flaps for the nipple-areola-sparing mastectomy is often more challenging than with the simple mastectomy or skin-sparing mastectomy. The use of a knife, scissors, or electrocautery depends on surgeon preference. As progress is made along the flap, a lighted retractor may be useful to ensure adequate retraction and flap thickness. The nipple is dissected from the underlying duct tissue sharply; this may be done with or without nipple tumescence. We have found that insertion of a 2-0 silk stitch through the nipple allows the assistant to elevate the nipple, which facilitates dissection of the underlying ductal tissue.

Once the ductal tissue is removed, the nipple is inverted and an additional nipple margin is taken and sent for frozen section. After the skin flaps have been created, removal of the breast from the chest wall including the pectoral fascia with the specimen must be accomplished. Often this dissection is most easily done by beginning at the lateral aspect of the breast and proceeding medially and inferiorly until the breast is completely removed up to the sternum. The breast can then be delivered through the incision and reflected cranially to facilitate dissection of the superior aspect away from the chest wall. If the mastectomy has been performed through an inframammary incision, then separation of the breast parenchyma beginning at the inframammary crease and progressing superiorly toward the clavicle is more feasible.

Management of the Axilla

The mastectomy procedure (non-skin-sparing, skin-sparing, or nipple-areola-sparing) can be combined with either a sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging of the axilla or a formal axillary lymph node dissection.

The mastectomy incision may also provide access to the axilla for dissection or sentinel lymph node biopsy. In those instances where the incision does not allow axillary access, a small counterincision in the axilla can be made or a lateral extension can be added to the primary incision. In cases where there is a preexisting incision on the breast, the mastectomy incision is designed to incorporate the previous incision. If it is not possible to include the previous incision, the area can be excised separately as long as this can be done without compromising the blood supply to the intervening skin bridge.

In the case of a patient with a positive axilla, a modified radical mastectomy is performed which combines a simple mastectomy, skin-sparing mastectomy, or nipple-areola-sparing mastectomy in an en bloc resection with the axillary lymph node dissection.

Complications

Complications of mastectomy include early and late events. In the early postoperative period, one must be vigilant for ongoing bleeding and hematoma formation, a complication reported in less than 5 % of patients [25]. The use of closed suction drainage will often allow early detection of ongoing bleeding, and a firm swelling on the chest wall usually indicates subsequent hematoma formation. This is often accompanied by complaints of increased pain from the patient. In these situations, the patient should be evaluated by the surgeon and a decision made whether to attempt compression or immediate evacuation. Flap ischemia or necrosis may also be seen in the early postoperative period and are often managed with watchful waiting and delayed debridement of nonviable tissue. Large areas of skin loss requiring debridement may necessitate split-thickness skin grafts or rotational flaps for coverage.

Late complications include infection and seroma formation. Manifestations of infections include superficial cellulitis, wound drainage, and skin breakdown. This may be treated with a combination of antibiotics, aspiration, or debridement. Particularly in the presence of a foreign body (tissue expander or implant), careful attention must be paid to the expedient administration of intravenous antibiotics. Infectious complications are generally handed in conjunction with the plastic surgeon when an expander or implant is present. Seroma formation is the most common complication after mastectomy, reported in 10–30 % of patients [26, 27]. While small fluid collections without evidence of infection may be observed, larger symptomatic seromas require aspiration and sometimes placement of a drainage catheter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree