Level

Lymph node group

Boundary

Superior

Inferior

Anterior (medial)

Posterior (lateral)

IA

Submental nodes

Symphysis of mandible

Body of hyoid bone

Anterior belly of the contralateral digastric muscle

Anterior belly of the ipsilateral digastric muscle

IB

Submandibular nodes

Body of mandible

Anterior belly of the digastric muscle

Stylohyoid muscle

IIA

Upper jugular nodes, anterior to XI nerve

Skull base

Horizontal plane defined by the inferior border of the hyoid bone

Stylohyoid muscle

Vertical plane defined by the spinal accessory nerve

IIB

Upper jugular nodes, posterior to XI nerve (submuscular recess)

Skull base

Horizontal plane defined by the inferior border of the hyoid bone

Vertical plane defined by the spinal accessory nerve

Lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle

III

Middle jugular nodes

Horizontal plane defined by the inferior border of the hyoid bone

Horizontal plane defined by the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage

Lateral border of the sternohyoid muscle

Lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle or sensory branches of the cervical plexus

IV

Lower jugular nodes

Horizontal plane defined by the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage

Clavicle

Lateral border of the sternohyoid muscle

Lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle or sensory branches of the cervical plexus

VA

Posterior triangle nodes (spinal accessory group)

Apex of the convergence of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles

Horizontal plane defined by the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage

Lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle or sensory branches of the cervical plexus

Anterior border of the trapezius muscle

VB

Posterior triangle nodes (transverse cervical artery group, supraclavicular group)

Horizontal plane defined by the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage

Clavicle

Lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle or sensory branches of the cervical plexus

Anterior border of the trapezius muscle

VI

Central (anterior) compartment lymph nodes (paratracheal, perithyroidal, Delphian)

Hyoid bone

Superior edge of the manubrium sternum bone

Common carotid artery

Common carotid artery

Level I contains the submental (IA) and submandibular (IB) nodes; it is bounded by the body of the mandible superiorly, the anterior belly of the contralateral digastric muscle anteriorly, the hyoid bone inferiorly, and the stylohyoid muscle posteriorly.

Level II contains the upper jugular lymph nodes; it extends from the skull base superiorly to the hyoid bone (clinical definition) or the carotid bifurcation (surgical definition) inferiorly; this group consists of the following two sublevels: nodes anterior to the spinal accessory nerve (IIA) and nodes posterior to the spinal accessory nerve (IIB).

Level III contains the middle jugular lymph nodes; it extends from the hyoid bone (clinical definition) or the carotid bifurcation (surgical definition) superiorly to the cricoid cartilage (clinical definition) or the omohyoid muscle (surgical definition) inferiorly.

Level IV contains the lower jugular lymph nodes; it extends from the cricoid cartilage (clinical definition) or the omohyoid muscle (surgical definition) superiorly to the clavicle inferiorly.

Level V contains the lymph nodes in the posterior triangle; it is bounded by the anterior border of the trapezius muscle posteriorly, the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly, and the clavicle inferiorly; this group consists of the following two sublevels: nodes superior to the level of the cricoid cartilage (VA, spinal accessory group) and nodes inferior to the level of the cricoid cartilage (VB, transverse cervical group).

Level VI contains the anterior lymph nodes from the hyoid bone superiorly to the suprasternal notch inferiorly, and the lateral border is formed by the common carotid artery.

8.3 Patterns of Regional Node Metastases

OSCCs are likely to present with nodal metastases in levels I, II, and III. Initial involvement of level IV is quite uncommon; metastatic spread to level V nodes is even more infrequent [9]. However, “skip metastases” or metastases to the inferior cervical nodes in level III or IV without demonstrable involvement of levels I and II are currently of concern [10, 11].

8.4 Evaluation of Regional Nodal Status

All patients with OSCC require careful assessment of their cervical nodal status for optimal treatment planning and determination of their prognosis.

8.4.1 Physical Examination

Palpation remains the first step in evaluating the neck of patients with OSCC. However, the diagnostic accuracy of this method varies depending on the body habitus of the patient and experience of the examiner. Both the specificity and sensitivity of the palpation method for diagnosing nodal disease are reportedly 60–70 % [12, 13]. In addition, some nodal regions are inaccessible to palpation, such as the parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal areas.

8.4.2 Imaging Studies

Imaging modalities currently available in routine clinical practice include ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) with or without CT.

US is a useful diagnostic imaging modality, which has been reported to have high sensitivity but low specificity for evaluating nodal diseases [14, 15]. US is advantageous because of its relatively low cost, its ability to capture accurate measurements of nodal size, and its compatibility with guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA); however, its usefulness is dependent on the experience of the clinician.

Cross-sectional imaging studies play a large role in the evaluation of nodal status. Although both MRI and CT can provide valuable supplemental information, CT appears to be slightly superior when appropriate criteria are used [15–18]. Regardless of the type of imaging studies performed, clinicians use the following criteria that were developed as an aid to determine whether a node is metastatic: (1) a node >1.0 cm (or >1.5 cm in the jugulodigastric region, >0.8 cm in the retropharyngeal region), especially when round; (2) decreased central attenuation in the node; (3) a poorly defined mass in the lymph node-bearing region; and (4) the combination of ill-defined borders and structures. If any of these criteria are present, the node must be considered to harbor metastasis [19, 20].

PET differs from other imaging modalities in that it evaluates metabolic activity rather than anatomical structures. PET has a lower resolution compared with CT or MRI, but this has been overcome with the advent of fusion-imaging technology, which combines the physiological data observed on a PET scan with the anatomical detail observed on a CT scan (PET/CT) [21, 22].

Although recent advances in modern technology have led to the development of various diagnostic imaging modalities as discussed above, none of these modalities alone can confirm a cervical lymph node metastasis (Fig. 8.1, Table 8.2).

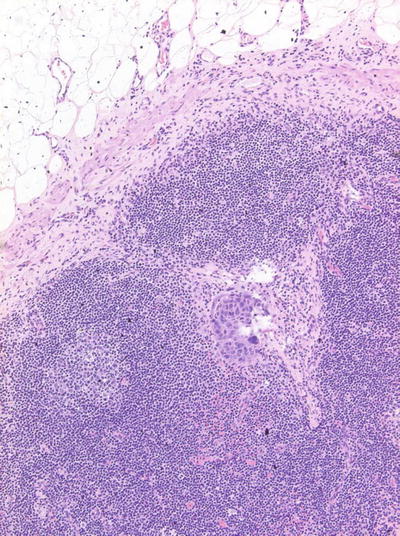

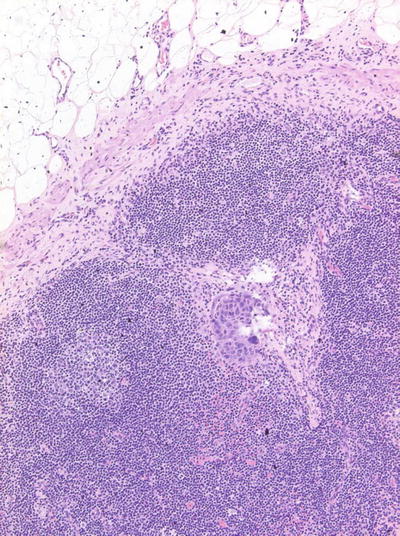

Fig. 8.1

Occult metastasis (micrometastasis)

Table 8.2

Sensitivity and specificity of imaging modalities used in evaluation of neck disease

Modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

US | 50–58 | 75–82 |

CT | 40–68 | 78–92 |

MRI | 55–80 | 82–92 |

PET/CT | 57–79 | 82–96 |

8.4.3 Pathological Examination

A patient’s cervical node status can be pathologically evaluated; however, pathological confirmation should be obtained only for clinically and radiologically suspicious nodes.

8.4.3.1 FNA

FNA is an accurate and reliable procedure with minimal morbidity that allows for a quick cytological diagnosis of suspicious nodes. For nodes that are difficult to access, guidance with US or CT is helpful [15, 23]. Sensitivity and specificity of FNA for masses of the head and neck have been reported as 97 % and 96 %, respectively [24]. The accuracy of FNA is directly related to the diagnostic capability of the cytopathologist and the quality of the material obtained. If a definitive diagnosis cannot be determined after repeated FNAs, the patient may require an open biopsy procedure.

8.4.3.2 Open Biopsy

The prognostic impact of an open biopsy of a suspicious lymph node remains controversial. Some reports have stated that an open biopsy increases the rates of local complications, local recurrences, and distant metastasis [20]. However, other reports indicate that biopsy of the neck does not imply a poor prognosis as long as adequate treatment is subsequently administered [25–27]. Currently, from a practical standpoint, an open biopsy of a suspicious node is rarely recommended for patients with OSCC.

8.5 Staging of Regional Node Metastasis

The staging system of regional lymph node metastases established by the UICC (outlined in Table 8.3) considers factors such as size, number, and laterality of the involved nodes.

Table 8.3

N-staging system for carcinoma of the oral cavity

Nx | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastases |

N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, 3 cm or less in greatest dimension |

N2 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

N2a | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

N2b | Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

N2c | Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

8.6 Prognostic Implications of Regional Node Metastasis

The presence of clinically apparent, histologically confirmed lymph node metastasis is the single most significant prognostic factor in patients with OSCC. In general, it has been observed that patients with lymph node metastasis have a 50 % lower overall survival rate than patients with early-stage disease, owing to neck metastases [1, 2]. However, the unfavorable impact of metastasis on survival varies depending on several factors.

The presence of extracapsular spread (ECS) of tumor, which is usually considered one of the most important predictor of poor prognosis, is not included in N-staging system (Fig. 8.2). ECS has been associated with higher rates of regional nodal recurrence, as well as significantly lower survival rates [31, 32]. As expected, ECS correlates with the size of the metastatic node and is typically found in cases of nodal metastases >3 cm [33]. However, it must be kept in mind that approximately 20 % of all lymph node metastases with ECS are <1 cm in diameter [31, 33]. Although a correlation between the degree of ECS and prognosis has not yet been established, Cater et al. have reported that macroscopic ECS carries a poorer prognosis than that of microscopic ECS [34]. In addition, the number of involved nodes affects the patient’s survival, i.e., survival rates are significantly lower when multiple nodes are involved [2]. The level in which the neck metastases occur, which is also not included in N-staging system, also is a significant factor in patient survival. Several studies have suggested that survival decreases as lymph nodes in lower levels of the neck become involved [35, 36].

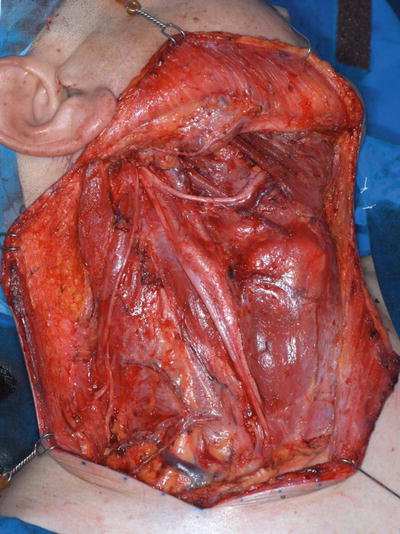

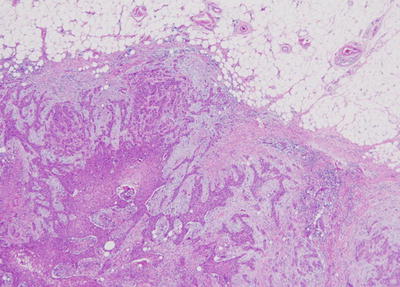

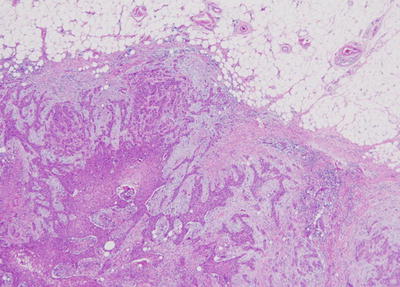

Fig. 8.2

Extracapsular spread of tumor

8.7 Principles of Neck Treatment

Early-stage regional node metastasis (clinically N1) can be treated with equal success by using either surgery or radiation therapy. In general, the choice of treatment modality is dictated by the modality selected to treat the primary tumor. For advanced cervical metastases (clinically N2 or N3), a combined approach of surgery and postoperative radiation or chemoradiation therapy is usually indicated. Management of the clinically negative (N0) neck is a subject of controversy.

8.7.1 Classification of Neck Dissection

Since the original description of radical neck dissection (RND) given by Crile in 1906, neck dissection has been the accepted standard treatment for regional metastases [37]. RND was popularized by Martin et al. in the 1950s [38], and since that time, surgical treatment of regional node metastases has mainly been RND. However, during the past few decades, RND has been modified in various ways on the basis of our increased understanding of the pattern of lymph node metastasis and the need to decrease postoperative morbidity [39].

The most recent classification of neck dissection was published in 2002 as a consensus statement proposed by the American Head and Neck Society and the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery and was primarily driven by the need to refine the selective neck dissection (SND) nomenclature [4] (Table 8.4).

Table 8.4

Classification of the neck dissection

Radical neck dissection (RND) |

Modified radical neck dissection (MRND) |

Selective neck dissection (SND) SND (I–III) SND (I–IV) SND (II–IV) |

Extended neck dissection (END) |

RND is the standard basic procedure for the dissection of cervical lymph node levels I–V with simultaneous resection of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, internal jugular vein, and accessory nerve.

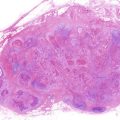

In modified radical neck dissection (MRND), levels I–V are also dissected, but with the preservation of one or more nonlymphatic structures (sternocleidomastoid muscle, spinal accessory nerve, and internal jugular vein) routinely removed in RND (Figs. 8.3 and 8.4).