CHAPTER 23 Management of Chronic Hepatitis B

Natural History of Chronic Infection

As stated in the previous chapter by Drs. Armstrong and Goldstein, risk of progression from acute to chronic infection differs according to the age of the subject at the time of infection: less than 1% in immunocompetent adults who contract hepatitis B virus (HBV) as opposed to 90% in newborns and 20% in childhood.1,2,3

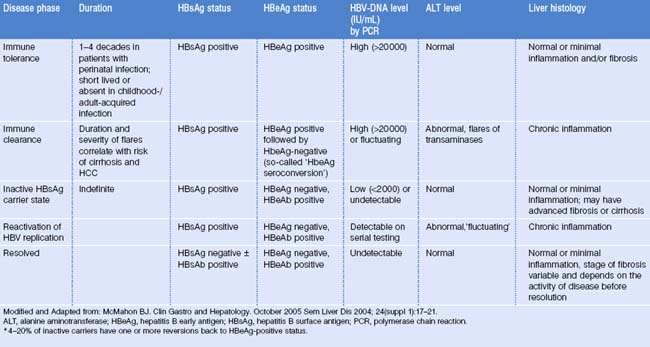

Once chronic HBV infection is established, its course is considered to consist of 5 phases (Table 23.1):

It is important to point out that:

Molecular testing in assessment and management of hepatitis B

This testing consists of two groups of assays:

Table 23.2 Commercially available tests for HBV DNA quantification

| Test | Units | Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid hybridization (Abbott) | Pg/mL | 1pg HBV DNA = 383 000 copies/mL (≈3 × 105 copies) |

| Hybrid capture (Digene) | Pg/mL | 1pg HBV DNA = 383 000 copies/mL |

| Branched DNA (Bayer) | Copies/mL | |

| PCR-amplicor (Roche) | Copies/mL | |

| TaqMan PCR | IU/mL | 1IU = 5.1 copies (105 copies = 20 000 IU) |

The five phases of chronic hepatitis B infection

In the immune tolerance phase spontaneous and treatment-induced HBeAg seroconversion (that is, loss of the HBeAg and production of HBeAb) is infrequent (<5% per year). HBV DNA levels are high, usually >20 000 IU/mL, transaminases are normal, and liver histology is benign. Prognosis is generally favorable for patients who are in this phase. A study of 240 patients in this phase from Taiwan (mean age 27.6 years) found that only 5% progressed to cirrhosis and none to HCC during a follow-up period of 10.5 years.4

The immune clearance phase (‘HbeAg-positive chronic hepatitis’) is characterized by flares of transaminases, believed to be manifestations of immune-mediated lysis of infected hepatocytes secondary to increased T-cell responses to hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) and HbeAg.5,6 These flares may precede HBeAg seroconversion, but many flares only result in transient decreases in serum HBV DNA levels without loss of HbeAg. Some flares may lead to hepatic decompensation.7,8 The duration of this phase and the frequency/severity of flares correlate with the risk of cirrhosis and HCC.9 So-called ‘seroconversion’ is the outcome of this phase; factors associated with higher rates of spontaneous HbeAg seroconversion include older age,10 higher transaminases levels,11,12 and HBV genotypes (B > C).13,14 In particular, genotype B is associated with a lower prevalence of HBeAg, HBeAg seroconversion at an earlier age, and more sustained virological and biochemical remission after HBeAg seroconversion.

Most patients who are in the fourth phase (‘reactivation of HBV replication/HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B’) come from a state of inactive carrier lasting a variable period of time. However, some patients progress directly from HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis to HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis. This phase is characterized by a fluctuating course both in terms of transaminases levels and HBV DNA levels. HBV DNA levels are usually lower than in the HbeAg-positive patients but may reach 20 or 200 million IU/ml. Transaminases were reported intermittently normal in 44% of 164 HBeAg-negative/HBeAb-positive patients followed for 21 months.15

This finding is important because it implies that a single HBV DNA level determination and a single transaminases level are not sufficient to differentiate patients in the inactive HBsAg carrier state from those with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis. Given the fluctuating course of the fourth phase, serial testing is more reliable than a single test.16

Recent studies in Europe, Asia, and the United States have all reported an increased prevalence of HBeAg-negative and a decreased prevalence of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis.17,18 This may be related to aging of existing carriers, decrease in new HBV infections, and increased awareness. This finding has important impact on treatment strategies.

The resolved phase of HBV infection is characterized by HBsAg seroclearance, which occurs at the rate of 0.5–1.0% per year in patients with chronic HBV infection.10,19

Factors influencing the natural history of chronic hepatitis B

Viral factors

AGE AT INFECTION/OLDER AGE: A Taiwanese study reported significant correlation between incidence of cirrhosis and patient’s age at study entry (p < 0.001).20 Peak age for symptomatic cirrhosis and HCC is 50–60 years.

MALE GENDER: Males are more susceptible to development of liver complications,21 and the male:female ratio for development of HCC is 5:1 in some populations.22 Crude mortality rate for HCC in Chinese males is 207 per 100 000 patient-years and 42.5 per 100 000 patient-years in females.

ALPHA FETOPROTEIN: A Taiwanese study reported cirrhosis to be more common in patients experiencing repeated episodes of severe acute exacerbations of chronic hepatitis B with AFP levels >100 ng/mL (57.1%, p < 0.001).20

NAFLD (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease): While there are no studies yet that address the potential effect of NAFLD on the progression of fibrosis in hepatitis B, this effect has been shown in hepatitis C.25

ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION: Alcohol abuse increases the risk of HCC 2–4-fold relative to alcohol abstinence.24 Heavy use of alcohol is also a risk factor for the development of cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis B. This corresponds to >20 grams/day in women and >30 grams/day in men.

COINFECTION: HIV is associated with more rapid onset of cirrhosis and incidence of HCC.10 HCV is associated with 2–6-fold increased risk of HCC in cirrhotic patients when compared to monoinfection.24 HDV is associated with 3-fold increased risk of HCC in cirrhotic patients compared to monoinfection.24

EXPOSURE TO AFLATOXIN: Aflatoxin is present in grains and in developing countries is known to contribute to the development of HCC. Some authors have proposed a synergism of action between aflatoxin and HBV in producing HCC.96

GENOTYPE: Evidence is currently emerging for a role of genotype in the progression of chronic HBV hepatitis.26 Genotype D is associated with more severe liver disease and higher incidence of HCC at a younger age (<40 years) than genotype A.27–29 Conflicting data exist for genotypes B and C.27–29

HBeAg/anti-HBe STATUS: There is conflicting evidence in regards to a possible association between HBeAg positivity and the risk of HCC. In a prospective study of 684 Taiwanese HBsAg-positive patients with histologically proven chronic hepatitis, those who were anti-HBe positive were equally at risk for the development of cirrhosis as those who were HBeAg positive.21 Another prospective Taiwanese study of >11 000 men30 found that the relative risk of developing HCC was much higher for HBeAgpositive/HBsAg-positive men than for HBeAgnegative/HBsAg-positive men and higher than for HBeAg-negative/HBsAg-negative men. However, because HBeAg/HBeAb status was recorded only upon study entry, it is likely that during the long follow-up (10 years) a substantial proportion of the HBeAg-positive patients seroconverted to HBeAb before developing HCC. For this reason it is difficult to conclude that HBeAg positivity is associated with an increased risk of HCC.

HBsAg SEROCLEARANCE: This produces favorable biochemical, virological, and histologic parameters, but may not reduce the risk of HCC in patients when seroclearance occurs after the age of 50 years and/or after development of cirrhosis.31–33

VIRAL LOAD: Prolonged low-level viremia is probably more influential in the development of cirrhosis and HCC than short-lived, high-level viremia.31 Recommendations of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) state that HBeAg-positive patients with serum HBV DNA levels above 20 000 IU/mL should be considered for treatment. However, there is evidence that active disease occurs at lower levels of HBV DNA, particularly in HBeAg-negative patients who have lower levels of HBV DNA than those with HBeAg-positive disease. In a Chinese retrospective study, 45% of HBeAg-negative patients with evidence of inflammation (raised ALT levels) had HBV DNA levels below 20 000 IU/mL.34 These findings suggest that using a threshold value of HBV DNA 20 000 IU/mL to differentiate active and inactive disease in HBeAg-negative patients will exclude a substantial proportion of patients with active hepatitis. For this reason HBeAg-negative patients with lower HBV DNA levels (2 000–20 000 IU/mL) undergo liver biopsy and be treated if significant inflammation of fibrosis are present.

cccDNA (= COVALENTLY CLOSED CIRCULAR DNA): Infection of hepatocytes with HBV is followed by conversion of the relaxed circular viral DNA genome (rcDNA) into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). cccDNA is localized to the nucleus, where it is transcribed to form the viral mRNA. cccDNA is an important pool of viral DNA that acts as a template for viral replication but is relatively resistant to existing therapies. Two Hong Kong studies have investigated the changes in cccDNA levels as chronic hepatitis B progresses.31,35

Screening High-Risk Populations for Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection By the Primary Care Physician

Table 23.3 lists the subject groups who are at risk for developing chronic hepatitis B. If an HBsAg-positive person is identified in a first-generation immigrant family, then screening should include second- and third-generation family members. Individuals found to be seronegative should then be vaccinated.

Table 23.3 High-risk groups who should be screened for HBV infection and vaccinated if seronegative

• Individuals from areas where there are high prevalence rates of HBV, including immigrants and adopted children: |

General evaluation of the HBsAg-positive patient by the primary care physician

At the initial consultation, patients with chronic hepatitis B infection (that is, HBsAg positive for >6 months) should undergo a thorough physical examination and a comprehensive patient history should be taken to identify risk factors for coinfection, alcohol use, and any family history of HBV infection and/or liver cancer. Laboratory tests should be undertaken to assess liver disease (complete blood count with platelets, hepatic panel including ALT, AST, total bilirubin, and prothrombin time/INR), markers of HBV replication (HBeAg/HBeAb, HBV DNA), hepatitis A (HAV) total antibodies, and at-risk patients should be tested for coinfection with hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis D virus (HDV), and/or HIV. Patients should also be screened for HCC (alpha fetoprotein, abdominal ultrasound or computed tomography [CT] scanning of the liver). It is common practice to test alpha fetoprotein every 6 months and perform ultrasonography of the liver every 6 months. The reliability of ultrasound studies is operator dependent, thus the capabilities of the sonographer should be taken into consideration. HCC surveillance is recommended for high-risk patients: Asian men over the age of 40, Asian females over the age of 50, all patients with cirrhosis, and patients with a family history of HCC, among others. A recent AASLD guideline specifically addresses this issue in relation to level of HCC risk for different patient groups (Table 23.4).36

Table 23.4 In all HBsAg-positive patients the primary care physician should assess the following at initial evaluation

It is recommended that all individuals with chronic hepatitis B who are not immune to hepatitis A should be vaccinated, because of the higher risk of clinically severe hepatitis A in patients coinfected with hepatitis B. Both primary care physician and specialist should counsel patients with chronic hepatitis B in regard to lifestyle modifications, such as reducing alcohol intake, and the risk of transmission to others. It is important to counsel them regarding screening and vaccination of sexual partners and second- and third-generation relatives, as well as regarding precautions to avoid exposing others to their blood and body fluids.1

Special situations encountered by the primary care physician

HBsAg-positive pregnant women

Vaccination breakthrough has been reported in newborns of mothers carrying HBV DNA >1.2 × 109 copies/mL (N >2.4 × 108 IU/mL). Lamivudine administered in the third trimester of pregnancy has been shown to be effective in reducing vertical transmission.37 Although the use of prophylactic lamivudine in pregnant women to prevent maternal–fetal transmission is still a matter of controversy, these patients should be evaluated case by case in conjunction with a specialist.

Further evaluation by the specialist

Defining any individual patient’s own phase within the natural history of HBV is the next step; this is best accomplished by referring the patient to a specialist (gastroenterologist/hepatologist) who will obtain serial monitoring of serum HBV DNA and transaminases over some time, eventually followed by liver biopsy. A liver biopsy may become indicated after the laboratory values obtained throughout the monitoring period (which may vary widely) are reviewed. Recommendations for monitoring patients chronically infected with HBV (inactive HBsAg carrier state, HBeAg-positive HBV infection, HBeAg-negative HBV infection) are included in AASLD, AGA, and ACG guidelines.39,70

Monitoring of serum transaminases and viral load (HBV DNA) over time is used by the gastroenterologist/hepatologist together with a liver biopsy in order to indicate the need for treatment. The different methods commercially available for measuring HBV DNA levels report results in international units ‘IU’. This is also the unit used in the most recently published medical guidelines.38,70

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree