Fig. 3.1

Bilateral accessory breast tissue in axillae

Breast Hypoplasia

This is the failure of one breast, or rarely two breasts, to develop normally and can be congenital or acquired. Congenital causes of hypoplasia include Poland’s syndrome, which is a group of conditions in which breast hypoplasia is associated with absence of, or hypoplasia of, the pectoralis major muscle, chest wall and varying degrees of syndactyly [3]. It is more common in men and is quite rare overall.

Management of Breast Hypoplasia

Treatment of hypoplasia or Poland’s syndrome depends on the degree of asymmetry and deformity. For mild asymmetry, reassurance may be all that is required. If the asymmetry is marked and readily noticeable, then the smaller breast can be augmented. If there is a lack of skin over the hypoplastic breast, then tissue expansion may be required prior to permanent implant placement. Another option is to reduce the larger breast. In many, a combination of techniques involving surgery to both breasts is required in order to achieve good overall breast symmetry. Pedicled or free flaps are usually needed if there is a large defect. Fat transfer (lipomodelling) is being used increasingly as a technique to help or aid the correction of breast hypoplasia, either alone or combined with the use of breast implants [4, 5].

Hypoplasia can also be associated with tubular or tuberous breasts. This deformity is caused by a constricting ring at the base of the breast that limits vertical and horizontal growth. Management of this condition is challenging. Tissue expansion combined with radial incisions in the deep aspect of the breast can improve the shape and appearance. The large nipple-areola complex often needs to be reduced. As in other types of hypoplasia, lipomodelling is being increasingly used with acceptable cosmetic results [5].

Juvenile Hypertrophy

Some patients have excessive development of the breasts, and this may occur during puberty or at the onset of lactation and is often referred to as juvenile hypertrophy. For patients with large breasts, a reduction mammoplasty improves the significant physical and psychological problems associated with this condition [6].

Abnormalities of Normal Breast Development and Involution

Defining what represents benign disease and what is part of normal breast development and involution is challenging [7]. The breast passes through phases related to the levels of circulating hormones and how these affect the breast. There are a range of conditions that should be considered as aberrations, rather than disease, and these take place against the normal process of breast development, cyclical change and involution.

Fibroadenoma

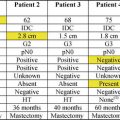

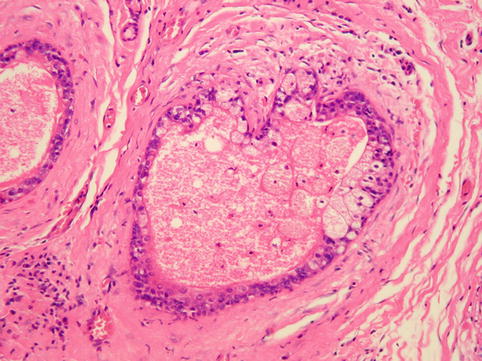

Fibroadenoma is best classified as an aberration of normal breast development. It arises from the breast lobule including the epithelium and the associated stroma and not from a single cell [8]. Fibroadenomas are under the same hormonal control as the rest of the breast and can increase in size during pregnancy, and they become less active with involution. The activity in the stromal element defines their classification. A simple fibroadenoma contains stroma of low cellularity. There are three separate types of fibroadenoma: common fibroadenoma, giant fibroadenoma and juvenile fibroadenoma (Fig. 3.1). There is no universally accepted definition of what constitutes a giant fibroadenoma, but most consider that it should measure over 5 cm in diameter. Juvenile fibroadenomas occur in adolescent girls and sometimes undergo rapid growth, but are managed in the same way as the common fibroadenoma (Fig. 3.2).

Fig. 3.2

Juvenile giant fibroadenoma (left breast)

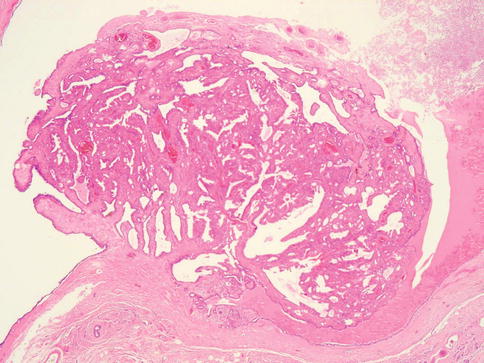

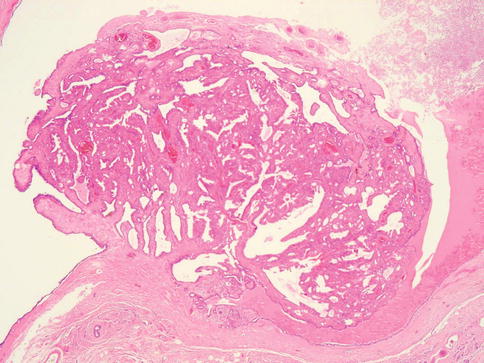

Phyllodes Tumours

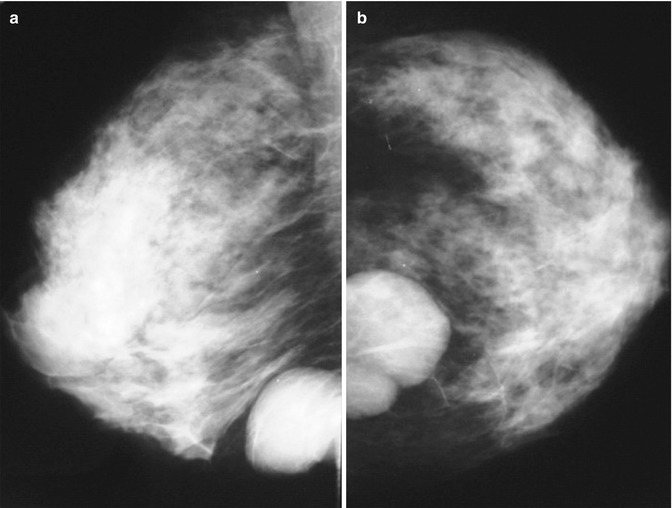

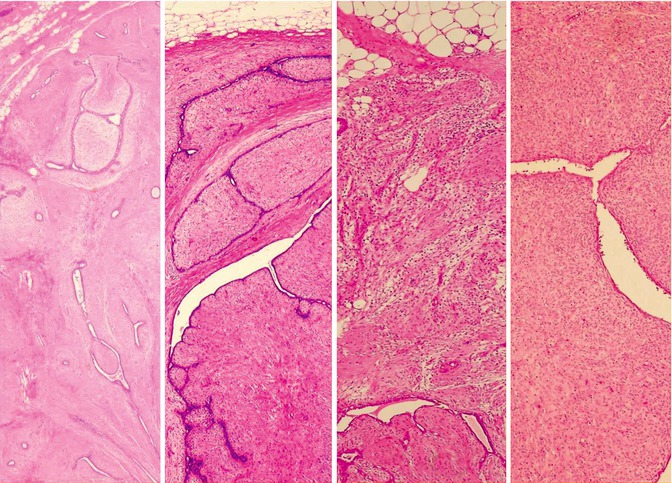

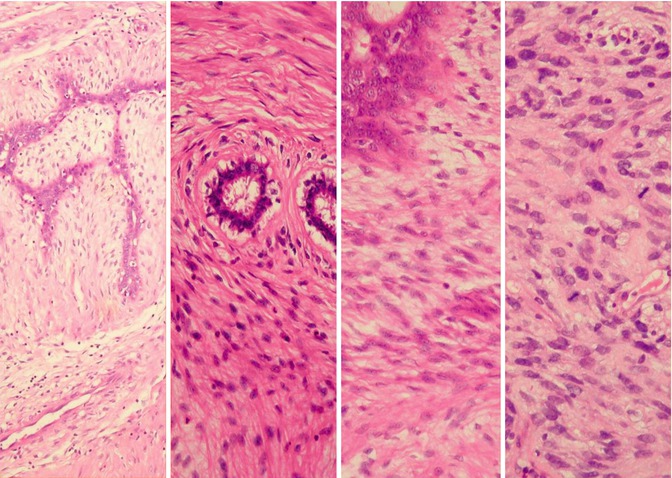

Phyllodes tumours are distinct pathologic entities. They are usually larger than fibroadenomas, occur in an older age group, have malignant potential and cannot always be differentiated from fibroadenomas clinically and on imaging. Phyllodes tumours focally can have an infiltrative margin, particularly in more aggressive forms, and phyllodes tumours range from benign (70 %) to borderline (25 %) to malignant (5 %) (Figs. 3.3, 3.4 and 3.5). About 10 % of benign phyllodes tumours recur after excision [9].

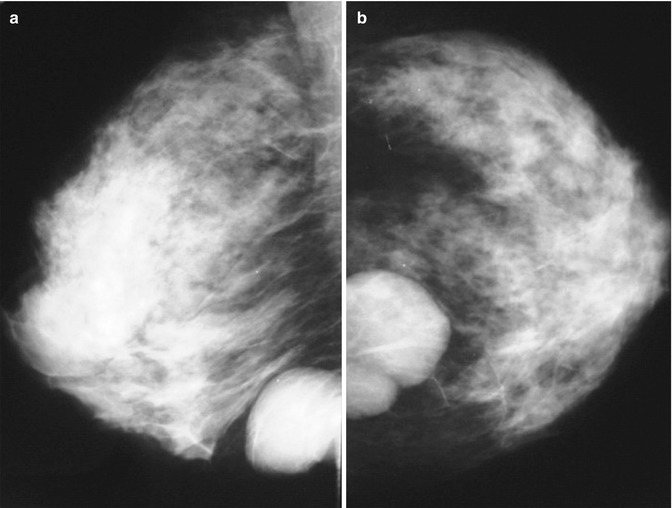

Fig. 3.3

Oblique (a) and craniocaudal (b) mammogram showing benign phyllodes tumour

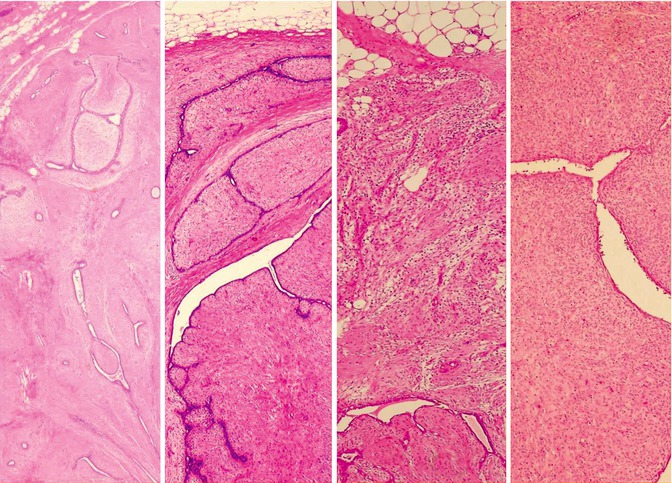

Fig. 3.4

Histology (low power) (left–right). (a) Simple fibroadenoma, (b) benign phyllodes, (c) borderline phyllodes, (d) malignant phyllodes

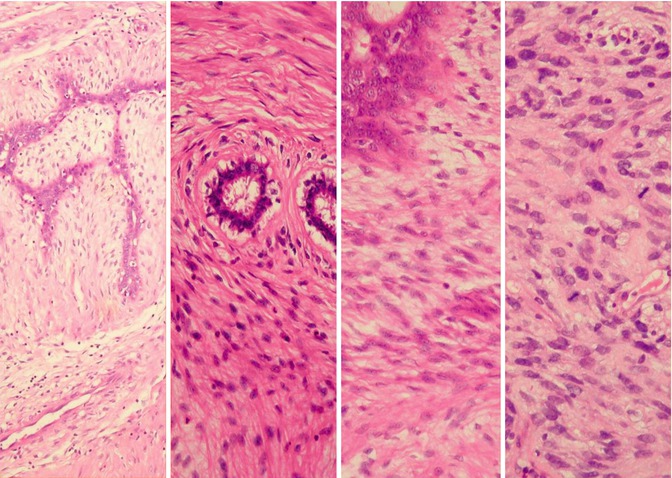

Fig. 3.5

Histology (high power) (left–right). (a) Simple fibroadenoma, (b) benign phyllodes, (c) borderline phyllodes, (d) malignant phyllodes

Management of a Discrete Mobile Mass in a Young Woman

A diagnosis based on imaging alone is acceptable, providing the patient is young (≤21 years old), and the lesion measures <3 cm. Otherwise, a histological diagnosis should be established by core needle biopsy. In patients with multiple fibroadenomas, two or more lesions should be sampled, and the remainder should be imaged and monitored. Any fibroadenoma over 4 cm requires full assessment by core biopsy. Multiple core biopsy passes (ideally 5–6 cores) should be performed in order to ensure that the lesion is adequately sampled and minimising potential sampling error.

Following a core biopsy pathologic diagnosis of a simple fibroadenoma, simple reassurance that the lesion is benign, with no malignant potential, is all that is required, and no further follow-up is necessary. However, excision is often performed at the request of the patient who despite this knowledge wishes the lesion to be removed. Larger lesions are usually excised first because they are often visible and symptomatic, but if they have been adequately sampled, they can be safely observed. Lesions over 5 cm are usually excised even if they are fibroadenomas on core biopsy because they are usually symptomatic, causing pain and/or discomfort. It is important to be certain that they are simple fibroadenomas and not phyllodes tumours.

How to Excise a Fibroadenoma

A cosmetic approach is recommended if a fibroadenoma is to be excised. Lesions in the lower half of the breast can be approached through an incision in the inframammary fold. Lesions in the upper half can be excised through a circumareolar incision or if near the axilla through an axillary skin crease incision.

Operative Technique

If an inframammary incision is used, then the incision is taken down to the rectus abdominus muscle and pectoral major muscle. The breast is elevated from the pectoral fascia without disturbing the fascia, and the fibroadenoma is approached from behind the breast. Fibroadenomas can be enucleated, and the best way to perform this is to open the capsule with blunt dissection using a pair of Metzenbaum scissors through the posterior aspect of the breast. The scissors are aimed at the fibroadenoma and opened, and this results in opening of the breast tissue down to the capsule of the fibroadenoma. Once the capsule is reached, the scissors are pushed into the capsule and opened, and this splits the capsule. A finger can then be inserted and the fibroadenoma enucleated. It usually remains attached at the point where the blood supply enters, and at this site the fibroadenoma is adherent to the capsule. Once the fibroadenoma is fairly mobile within the capsule, it is usually possible to deliver it through the wound and divide any residual attachment to the capsule under direct vision with diathermy. The defect in the back of the breast is closed with absorbable interrupted sutures. Bleeding is rarely a problem but careful inspection of the capsule is performed, and any bleeding is stopped with diathermy. The inframammary wound is then closed carefully in layers.

If the fibroadenoma is being approached through a circumareolar incision, then having deepened the incision the plane between the subcutaneous fat and the breast fat is entered. This may be facilitated by hydrodissection using normal saline or a 1 in 500,000 adrenaline in normal saline solution. Once the breast tissue over the fibroadenoma is reached, then the tissue is opened down to the fibroadenoma using scissors pointed at the fibroadenoma with the scissors being opened to divide the overlying breast tissue, and then the capsule around the fibroadenoma is also split with scissors. Enucleation is performed with a finger, and the lesion is delivered through the tunnel into the wound and the blood supply of the fibroadenoma divided under direct vision. No sutures in the breast tissue are needed. The skin is closed in layers with absorbable sutures. Small fibroadenomas can be removed using vacuum-assisted core biopsy devices [10].

Most phyllodes tumours are benign and require total removal but do not require to be widely excised. When removing a benign phyllodes tumour, the lesion together with the capsule is excised with the aim of achieving clear margins clear (≥1 mm) of the phyllodes tumour. If following excision of an apparently simple fibroadenoma a phyllodes tumour is diagnosed and the surgeon is confident that the lesion has been excised completely, then careful follow-up, rather than re-excision, is appropriate. Borderline and malignant phyllodes may require a wider excision.

Aberrations of Cyclical Activity

Nodularity

Focal breast lumpiness is one of the most common reasons for a woman to be referred to a breast clinic. Lumpy nodular breast tissue is common. Women with a focal area of nodularity should be assessed with imaging, and providing there is no abnormality visualised on ultrasound and/or mammography, then the patient can be safely reassured. These young women with nodular breast tissue were previously considered as having fibroadenosis or fibrocystic disease, but these terms are not appropriate and should not be used because these women usually have normal breast tissue if biopsy is performed. Breast cancer can present in a young woman with asymmetrical nodularity, and if there is clinical suspicion in the face of normal imaging, then a core biopsy or fine-needle aspirate of the palpable mass should be performed.

Breast Pain

Up to 70 % of women experience breast pain at some point in their life. What women describe as breast pain can be pain that originates from the breast or is referred from adjacent areas, such as the chest wall. Breast pain is a rare symptom of breast cancer, and in one 10-year study period in Edinburgh of 8,504 patients presenting with breast pain, only 220 (2.7 %) were subsequently diagnosed as having breast cancer. During the same period 4,740 were diagnosed with breast cancer, and this means that only 4.6 % of women with breast cancer have pain as a presenting symptom [11].

Cyclical breast pain is very common and is now regarded as physiologic and not pathologic. Severe or prolonged pain is considered an aberration of normal cyclical activity.

Management of Breast Pain

It is important to differentiate between pain arising from the chest wall and true breast pain. Features suggesting that the breast pain is referred pain from the chest wall include:

Unilateral and brought on by activity

Very lateral or medial in the breast

Can be reproduced by pressure on a specific area of the chest wall

Careful clinical examination is essential. A patient complaining of breast pain should have an examination lying on her side allowing the breast to fall away from the breast wall, and the underlying ribs and muscles should then be palpated. The patient should be asked to indicate if there is any localised tenderness on the palpation of the chest wall and whether the pain elicited is similar to that they normally suffer. If the patient has pain in the lower part of the breast, then the underlying chest can be checked by lifting the breast upwards with one hand while palpating the underlying chest wall with the other hand.

The mainstay of treating breast pain is reassurance that there is no serious underlying problem [12]. Lifestyle issues are important and it is not uncommon for women who spend many hours at a desk, sitting in front of a computer, to have chest wall pain. If, on examination, the pain is very localised to one specific spot on the chest wall, then infiltration of the site of the pain with a combination of prednisone (40 mg in depot form) combined with a long-acting local anaesthetic such as bupivacaine can produce long-lasting pain relief.

Pain in bed at night is a problem for many women. Wearing a soft supportive bra stops the breast pulling down on the chest wall, and this helps many women to sleep. There have been numerous studies looking at the role of caffeine, essential fatty acids, and diet as a contributing factor for breast pain. There is little evidence that activities such as cutting out caffeine, taking evening primrose oil, or transferring to a low-fat diet are beneficial [13–16].

The treatment that has been shown to have greatest efficacy in true breast pain is tamoxifen [17]. Although most commonly given for cyclical pain, it can help true noncyclical breast pain. It is best tolerated in a dosage of 10 mg a day [18]. Compared with other treatments, such as danazol, there are fewer adverse events with tamoxifen [18]. It is possible to restrict the use of tamoxifen to the luteal phase of the cycle, and this can relieve pain in up to 85 % of women [19, 20].

A variety of nonhormonal agents have been tried for breast pain. Although some studies have reported an improvement with soya milk, there is general non-compliance in studies published to date [21]. Agnus castus, a fruit extract, has been shown in one trial to improve breast pain [22]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have also been shown to improve breast pain [23].

Aberrations of Breast Involution

Palpable Breast Cysts

Approximately 7 % of women at some point in their life develop a palpable breast cyst [24]. Such cysts constitute 15 % of all discrete masses. Cysts are distended in involuted lobules and are most common in the perimenopausal period. Women generally present with a smooth, discrete breast lump that can be painful and is sometimes visible. Cysts have characteristic features on ultrasound and on mammography. Once diagnosed on imaging, simple cysts do not need to be aspirated unless they are symptomatic, complex or indeterminate. Cyst fluid should only be sent for cytology if it is blood stained, safely discarding non-bloody fluid.

After a cyst has been aspirated, the breast should be examined to check that the palpable mass has disappeared. Between 1 and 3 % of patients who have cysts in their breasts also have a carcinoma. It is therefore important that both breasts are assessed by careful clinical examination and appropriate imaging when necessary.

Management of Patients with Cysts

Following aspiration, the majority of patients require no clinical follow-up. It is only those patients who have multiple bilateral cysts who merit any further clinical follow-up. The only reason for seeing these women is that they tend to continue to develop multiple bilateral cysts and return at regular intervals to breast clinics. Regular assessment by clinical assessment and ultrasound allows them to be reassured without the need for regular re-referral. During follow-up only symptomatic cysts should be aspirated. Studies show a small but not a significant increased risk of breast cancer in women with palpable breast cysts [25].

Sclerosis

During evolution, the stroma of the breast changes and it is not uncommon to develop localised areas of excessive fibrosis or sclerosis. Pathologically, sclerosing lesions can be separated into three groups: sclerosing adenosis, radial scars, and complex sclerosing lesions. The only difference between radial scars and complex sclerosing lesions is that radial scars are small and complex sclerosing lesions are larger. Sclerosing lesions are only clinically important because they cause diagnostic problems during imaging and breast screening.

Management of Sclerosing Lesions

They are normally identified on imaging with only a few palpable on clinical examination. A core needle biopsy should be performed. There is some concern that a standard 14-gauge core biopsy might miss a small area of DCIS in association with a radial scar or a complex sclerosing lesion. For this reason larger, vacuum-assisted core biopsy or a needle localisation excision biopsy is required to make a definitive diagnosis [26]. Debate continues as to whether all radial scars should be excised because of their association with invasive and in situ breast cancer [27].

Duct Ectasia

The major subareolar ducts dilate and shorten during ageing or involution. By the age of 70, 40 % of women have substantial duct dilatation. Some of these women develop both duct dilatation and duct shortening that manifests as nipple retraction with or without nipple discharge, and occasionally women present with a palpable periareolar mass that can be hard or doughy from the dilated ducts filled with inspissated secretion. The discharge in patients with duct ectasia is usually “cheesy” in consistency, and the nipple retraction is classically symmetrical or slit like.

Management of Duct Ectasia

Imaging can usually diagnose duct ectasia, and for patients with nipple inversion who have no suspicious features clinically or radiologically, surgery is not required. Surgery is only indicated in multiduct discharge, if it is troublesome or there is an inverted nipple and the patient wants the nipple to be everted. Duct ectasia (Fig. 3.6) should not be confused with periductal mastitis which is a separate condition [28–30]. Once cancer has been excluded, patients with duct ectasia can be reassured and do not require follow-up.

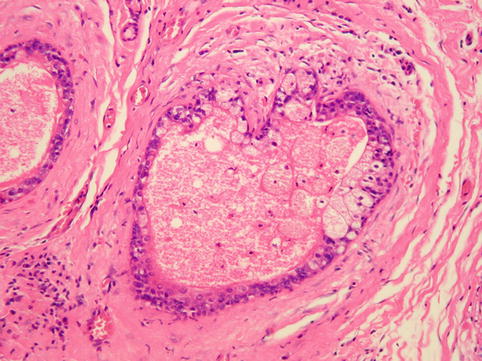

Fig. 3.6

Histology showing features of duct ectasia

Duct Papillomas

Duct papillomas can be single or multiple. They are common and generally are considered as aberrations rather than true neoplasms as they show minimal malignant potential. The problem is that they are very common and can be visualised on imaging and are often incidental findings during screening. Core biopsy can identify that the lesion is papillary, but often cannot always exclude malignancy. More often than not, the pathologist will give this the diagnosis of a “papillary neoplasm of uncertain clinical significance”, prompting removal of the lesion.

Management of Duct Papillomas

Options include observation if there is no evidence of atypia or excision (Fig. 3.7). Papillomas can be removed with vacuum-assisted core biopsy. They are often excised to exclude malignancy, but given their frequency and low rate of malignancy, there needs to be greater consideration as to whether all such lesions need to be removed [31].

Fig. 3.7

Histology of a benign intraduct papilloma

Nipple Retraction

Slitlike retraction of the nipple is characteristic of benign disease (Fig. 3.8), whereas nipple inversion, when the whole nipple is pulled in, occurs in association with both breast cancer and inflammatory benign breast conditions (Fig. 3.9). For patients with congenital nipple retraction and benign acquired nipple retraction, which is unsightly and does not respond to conservative measures such as suction devices or nipple shields, surgery which may require duct division or excision is successful at everting the nipple (Fig. 3.10). Women need to be informed that duct excision can result in loss of ability to breastfeed and can result in loss of, or reduction in, nipple sensation, and occasionally some women develop nipple hypersensitivity.

Fig. 3.8

Benign slitlike nipple inversion

Fig. 3.9

Nipple inversion in association with malignancy

Fig. 3.10

Bilateral nipple inversion (a) before and (b) after nipple eversion surgery

Nipple Discharge

Nipple discharge accounts for approximately 5 % of all referrals to a breast clinic and is a frightening symptom because of the fear of cancer [32]. More than 95 % of women presenting with nipple discharge will have a benign cause [33]. Discharge associated with significant underlying pathology is spontaneous, more likely to be unilateral, arise from a single duct, be persistent (defined as more than twice a week) and be blood stained. One study found that in women with nipple discharge significant risk factors for malignancy were blood staining of the discharge (odds ratio 3.7) and spontaneous discharge (odds ratio 3.2) [34].

Investigation of Nipple Discharge

Physical examination should include application of firm pressure around the areola as the presence of a dilated duct will result in the production of discharge through the nipple (Fig. 3.11). The nipple should also be squeezed with firm digital pressure, and if fluid is expressed, then the site and character of the discharge recorded. Age is an important predictor of malignancy, and in one study 3 % of patients younger than 40, 10 % of patients between the ages of 40 and 60 and 32 % of women older than 60 years of age who had nipple discharge as their only symptom were found to have cancer [35]. Mammography has a low sensitivity of only approximately two thirds in women with nipple discharge [36, 37]. Ultrasound can identify visible lesions within the breast ducts including papillomas [38]. Imaging the ductal tree by ductography or galactography can identify intraductal lesions, but this investigation has a sensitivity of only 60 % for malignancy [33, 39]. Nipple cytology, ductoscopy and ductal lavage have a role in routine assessment of nipple discharge [40–44]. Of these techniques, ductoscopy is the most accurate but takes longer than 6 months to learn and the equipment is costly [45].

Fig. 3.11

Example of nipple physiological multiduct, multicolour discharge

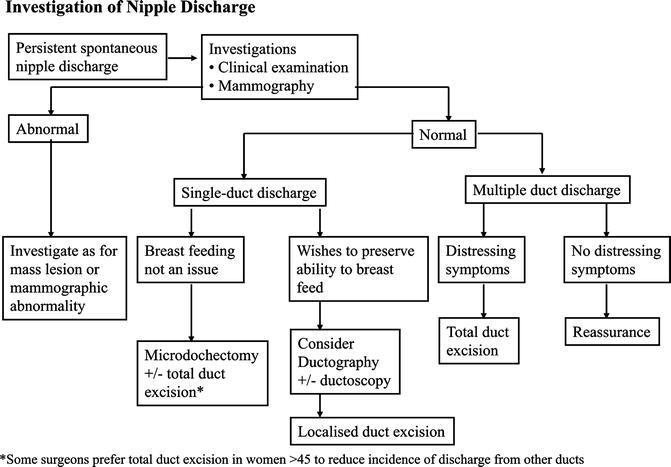

Management of Nipple Discharge (Fig. 3.12)

Fig. 3.12

Flow diagram for investigation of nipple discharge

If clinical examination demonstrates a mass lesion visible on mammography or ultrasonography, then image-guided core biopsy of this lesion should be performed and the patient managed appropriately [38]. Otherwise, if no abnormalities are found on clinical examination, surgery is indicated for spontaneous discharge from a single duct that has one or more of the following characteristics:

Blood stained.

Persistent and stains clothes.

Associated with a mass.

New development in a woman of over 50 years of age.

The discharge is not thick or cheesy.

Discharge from multiple ducts normally only requires surgery when it causes distressing symptoms.

Options for surgery for single-duct discharge include microdochectomy or total duct excision. Current evidence suggests that total duct excision is more effective than microdochectomy at establishing a specific diagnosis and has a lower chance of missing any malignancy that is present [46]. For this reason, many units perform total duct excision in women over the age of 45 and only perform microdochectomy in younger women [47].

Microdochectomy

Microdochectomy can be performed through a circumareolar or radial incision. The discharging duct is cannulated either with a probe or a blunt-ended needle, through which methylene blue can be injected. Both techniques allow the involved duct to be identified underneath the nipple through the skin incision. The discharging duct, once it has been identified, is dissected distally into the breast over a distance of about 5 cm. Almost all significant disease that causes nipple discharge involves the proximal 5 cm [44, 48]. Following excision of the involved duct, the remaining distal duct in the breast should be inspected, and if there is a visible dilated duct passing into the breast, then further tissue can be excised, or the duct opened and any visible lesion in the duct removed. This is because some DCIS lesions develop at some distance from the nipple, and these produce nipple discharge, but can be missed on microdochectomy. They are diagnosed only if the distal ducts are inspected and excised if abnormal.

Total Duct Excision

Total duct excision is best performed through a circumareolar incision based at 6 o’clock. If the operation is being performed for periductal mastitis, then the patient should receive perioperative and postoperative appropriate antibiotic therapy such as amoxicillin-clavulanic acid or a combination of erythromycin and metronidazole hydrochloride. Having deepened the incision, dissection continues towards the nipple. It is usually better to use scissors or a knife near the nipple rather than cautery. Dissection with Metzenbaum scissors is continued under the areola down either side of the major ducts. Curved tissue forceps are then passed around the ducts, and all the ducts that have been encircled are delivered into the wound. Having secured the distal ducts with tissue forceps, they are then divided from the underside of the nipple.

If a total duct excision is being performed for periductal mastitis, it is important to excise all the ducts up to the nipple skin [49]. If the surgery is being performed for nipple inversion, then the ducts can be simply divided. Otherwise, approximately 2–5 cm of ducts are excised [50]. It is often useful to close any defect in the breast with absorbable sutures. If the nipple was inverted prior to surgery, then it is important to evert the nipple before wound closure, and this may involve dividing any scar tissue that is distorting the nipple. The nipple may need to be squeezed between the thumb and index finger to break down any adhesions to maintain eversion. Sutures are rarely if ever required to maintain eversion because if the nipple does not remain everted without sutures, then it will invert even if sutures are placed. No drains are needed and the wound is closed in layers with absorbable sutures. Patients should be warned before surgery that this operation will reduce nipple sensitivity in up to 40 % of women [49].

Benign Disease in Men

Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia is the growth of breast tissue in males to any extent. It is entirely benign and usually reversible. It is seen most frequently during puberty and old age. In boys aged 10–16 years of age, between 30 and 60 % have breast enlargement, and this usually requires no treatment as 80 % of this breast enlargement resolves spontaneously within 2 years.

Surgery for gynecomastia is not straightforward and should be performed by an experienced surgeon. Embarrassment and persistent enlargement of the breast tissue are both indications for surgery.

Gynecomastia commonly affects older men between the ages of 60 and 80 (Fig. 3.13). In the majority, it does not seem to be associated with any significant endocrine abnormality [51, 52]. There are a variety of specific causes including several classes of medications. A careful alcohol and drug history and an examination often reveal the cause.

Fig. 3.13

Bilateral senescent gynecomastia

Patients with recent progressive breast enlargement without any easily identifiable cause require a hormonal profile and blood tests to exclude a metabolic cause. Mammography and ultrasound can differentiate between breast enlargement due to fat or gynecomastia and can identify malignancy if this is suspected. Breast cancer usually presents as a firm lump that is eccentric, whereas gynecomastia is concentric. If imaging is suspicious, then core biopsy should be performed.

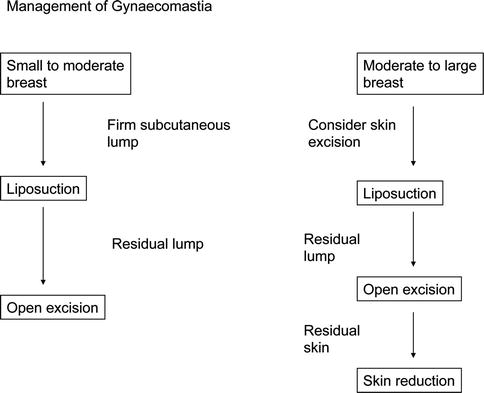

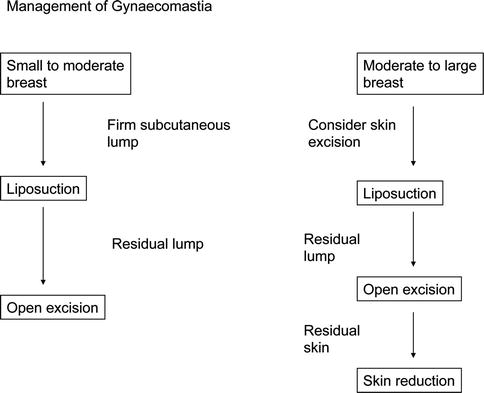

Management of Gynecomastia

In drug-related gynecomastia, withdrawal of the drug or change to an alterative treatment should be considered. Gynecomastia is seen in bodybuilders who take anabolic steroids, and some of these have learned that by taking tamoxifen, they can counteract these symptoms. Bodybuilders should be encouraged to reduce or stop steroids. In young men, gynecomastia is seen in both heavy beer and lager drinkers and in young men who smoke cannabis. There are phytoestrogens in beer and lager; cannabis is also estrogenic in its action.

In patients with symptomatic gynecomastia, both tamoxifen and danazol improve symptoms, but recurrence when the drug stops can be a problem [53, 54]. Tamoxifen at a dose of 10 mg is effective and produces less side effects than 20 mg. Surgery for gynecomastia is not straightforward and should normally be performed by experienced breast surgeons or plastic surgeons. It often involves a combination of excision of breast tissue and liposuction occasionally with removal of overlying skin [55–57] (Fig. 3.14).

Fig. 3.14

Algorithm for the management of gynecomastia

Benign Neoplasms and Proliferations

Epithelial Hyperplasia

This is an increase in the number of cells lining the terminal duct lobular unit. Previously called epitheliosis or papillomatosis, these terms are no longer in common use. The degree of hyperplasia can be graded as mild, moderate or severe. Atypical hyperplasia is diagnosed if the hyperplastic cells also show cellular atypia. Atypical hyperplasia is one of the few benign conditions that are associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer. The absolute risk of breast cancer in women with atypical hyperplasia who do not have a first-degree relative with breast cancer is about 8 % at 10 years [58]. However, in women who do have a first-degree relative with breast cancer, the risk increases to 20–25 % at 15 years [58]. Hyperplasia can consist of cells with so-called “ductal” or “lobular” morphology. Atypical hyperplasia of lobular type is now classified together with lobular carcinoma in situ as a single entity called lobular intraepithelial neoplasia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree